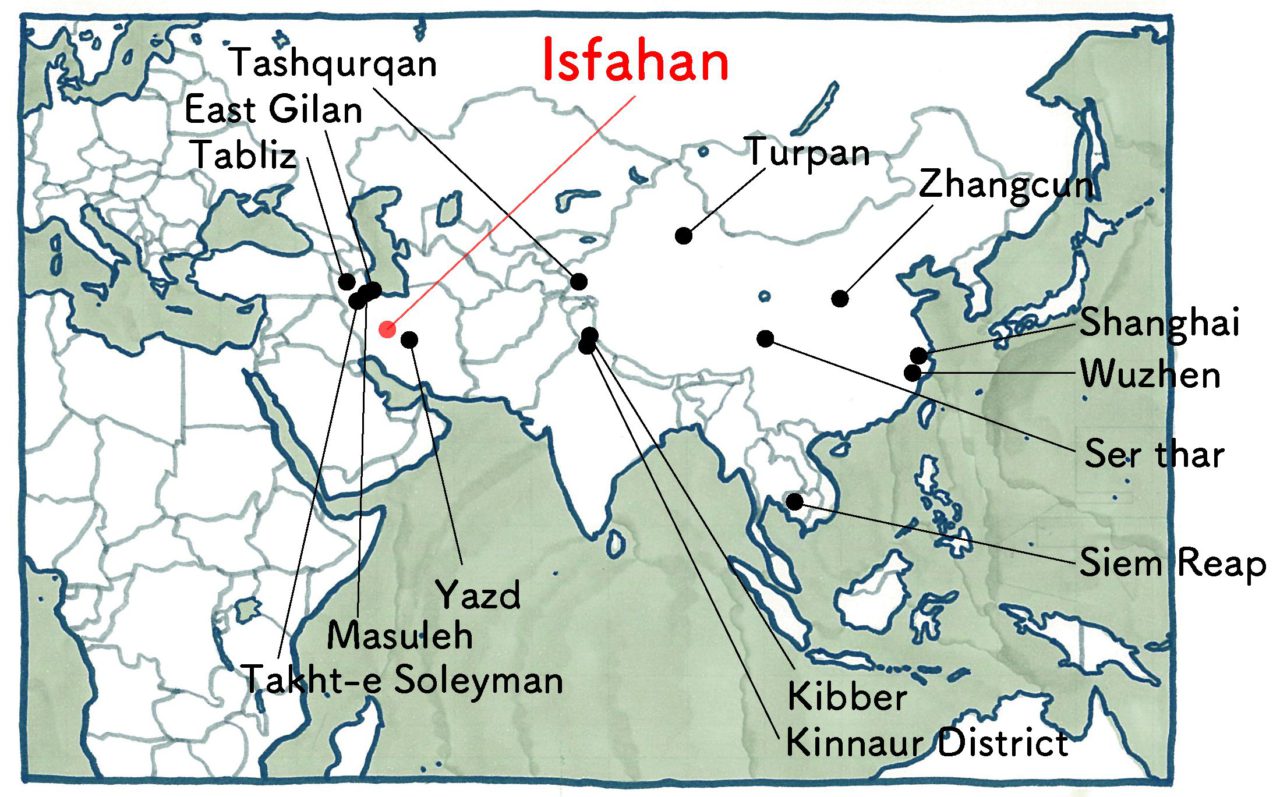

Series Traveling Asia through a Window

Religion and Cities: Isfahan, Iran

19 Feb 2020

I experienced no small amount of culture shock in Iran, as it was the first Islamic country I visited. Many of the people I passed on the street were male, while bus seats for men and women are divided. For whatever reason, men’s bathrooms only have private stalls. Prayer takes place three times a day, and a beautiful Adhan (call to prayer) rings throughout the city to let everyone know when it is time. Every part of life in Iran has been shaped by a single religion. Yet someone who has flung himself into a world as different as this one is still able to live his regular life. It’s hard to believe.

According to Besim S. Hakim’s Arabic-Islamic Cities, Islamic land use and architecture has historically come to exist by way of extremely minute rules based on the Quran and Hadith (records of words and actions of the prophet). He says that the central concept behind these rules is harm. In other words, strict provisions regarding everything from the width of roads, the placement of entrances, and the height and position of windows to drainage methods exist as methods of “mediation” that prevent harm from being done to others or received.

It is a way to live in peace in large gatherings, and traces of these rules can still be found in cities. One may even be able to say that the Islamic city is like a sculpture that has been carved using these strict rules.

-

A window high enough to prevent people from peeking in (Isfahan)

-

A flat and featureless wall. One begins to see the fact that the roof’s drainpipes eventually bury themselves inside this wall as something to prevent “doing harm” by leaking while also preventing one from “receiving harm” by having their pipes broken. (Isfahan)

For example, many windows in residential areas of Iran are not at eye level, but are instead built higher. This is to prevent people peeking in from the outside, protecting the privacy of those on the inside.

I always felt that the walls were flat and featureless as I walked through the country’s residential districts, but I now realize this was a sight created by a method used to keep harm from coming to any party. The “breathing” holes I saw before in Yazd, Iran can also be seen in this privacy-focused perspective. I believe the same issue can also be found within the “lifted roofs” of Turpan, an Islamic region of China.

Furthermore, the lattice windows known as mashrabiyas briefly touched upon in the previous issue on Masuleh seemed to be created particularly so that women could look outside without being seen. This too is another example of Islamic customs and climate acting as factors that are even incorporated into window design.

-

A mashrabiya softening the light (Isfahan)

Looking at photo above, we can see that mashrabiyas do a better job of softening outside light than a regular entrance. They are a way to prevent “harm” coming not only from gazes from others, but even from the too-strong sunlight that pours down on the region. Perhaps Japanese people, with their familiarity with sliding paper screens, will have an easy time understanding these.

However, compared to the simple designs found in the village of Masuleh, another part of Iran, the mosques in the city of Isfahan still contained many unbelievably elaborate mashrabiyas. At some point, these seem to have surpassed their original function in order to now act as free forms of ornamentation made of brick, wood, stone, and more.

-

A simple mashrabiya made out of offset bricks (Isfahan)

Isfahan is especially well-known for its tile work, and the beauty of the tile patterns inside its early-modern mosques cannot be surpassed. Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque, built in the 17th century, uses tile patterns as mashrabiyas to successfully merge its openings with its decoration-covered walls without interruption.

-

Openings that maintain continuity with interior ornamentation

-

Turning tile work into a mashrabiya (Isfahan)

One can also look at Nasir al-Mulk Mosque in the town of Shiraz, further south from Isfahan. Built in the 19th century, it combines wooden mashrabiyas with stained glass. It is so photogenic that photography sessions are held by massive tours there, and one could consider its current state as yet another piece adorning the mosque’s history.

-

Stained glass combined with mashrabiyas (Shiraz)

When I visited a mosque at night, I saw countless locals with their shoes off and engrossed in a Quran held with one hand, or perhaps drowsily spending time as they wished. The people of the city, whose lives are primarily formed by Islam, always have a big roof they are free to enter inside.

-

A mosque at night (Shiraz)

This mosque, the flat and featureless residential areas, and the mashrabiyas everywhere shared the same world, and it felt as though they all participated in that totality. Though I had come into contact with a small part of Islam’s strictly established precepts that consider harm as a basic concept, I still found myself a little envious of what I saw after coming from another country to steal a glimpse at this totality.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Shizuoka prefecture in 1992 and grew up in Tokyo. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. From April 2014 he began life as a graduate student in architectural history, studying under Norihito Nakatani. In June of 2014 he proposed a restoration plan for residents of Izu Ōshima for a sediment-related disaster. This would become his graduation project. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In Yilan County,Taiwan, he worked as an intern at Fieldoffice Architects.