Series Traveling Asia through a Window

The Overhanging Village : Kinnaur District, India, Part 1

14 Mar 2018

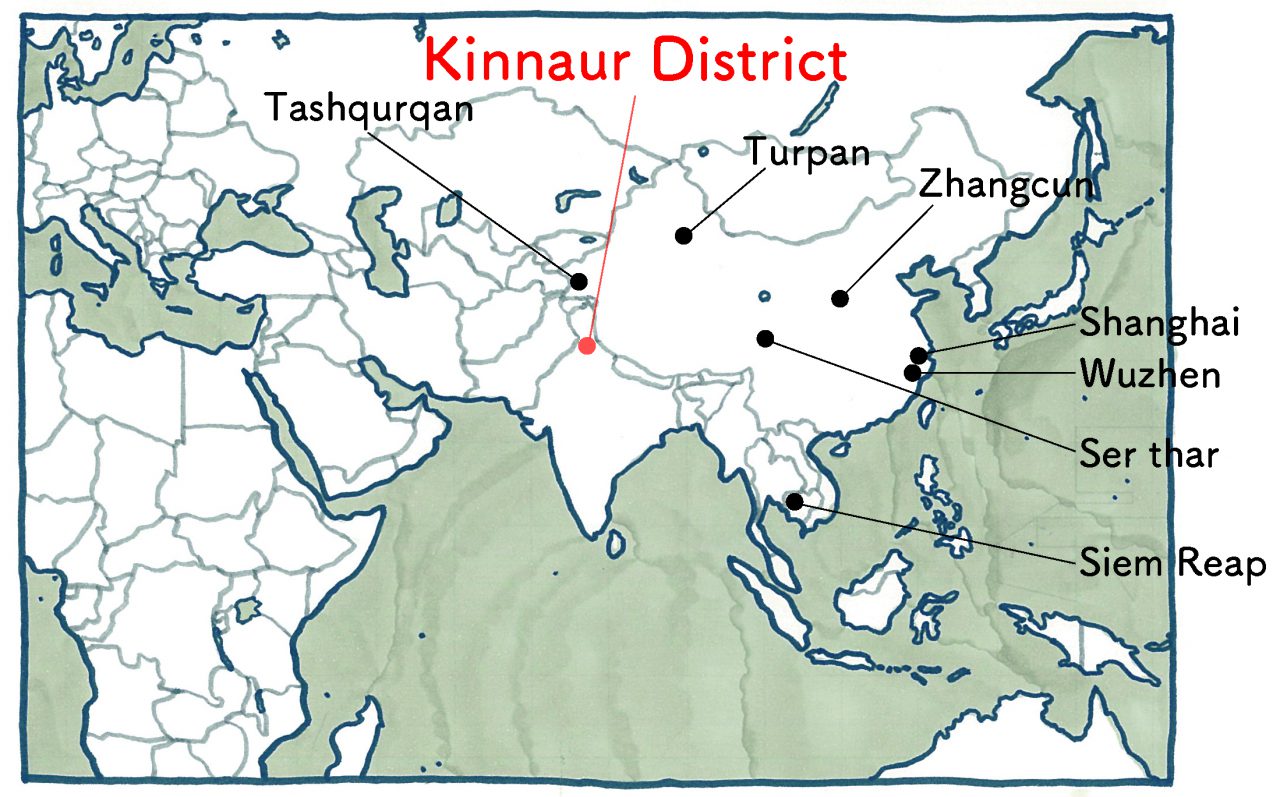

In the northern Indian state of Himachal Pradesh is a region inhabited by people known as the Kinnauris. It is a high-elevation region located in the northwest Himalayans, with the Tibet Autonomous Region to its east. I first developed an interest in the district of Kinnaur when I was flipping through Takeo Kamiya’s The Guide to the Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent (TOTO Publishing, 1996) and found myself stunned by a photograph of a Hindu temple known as Bhimakali Temple.

The temple is located in the village of Sarahan, more than a full day’s journey from New Delhi requiring hours upon hours on multiple busses along dangerous cliffside roads.

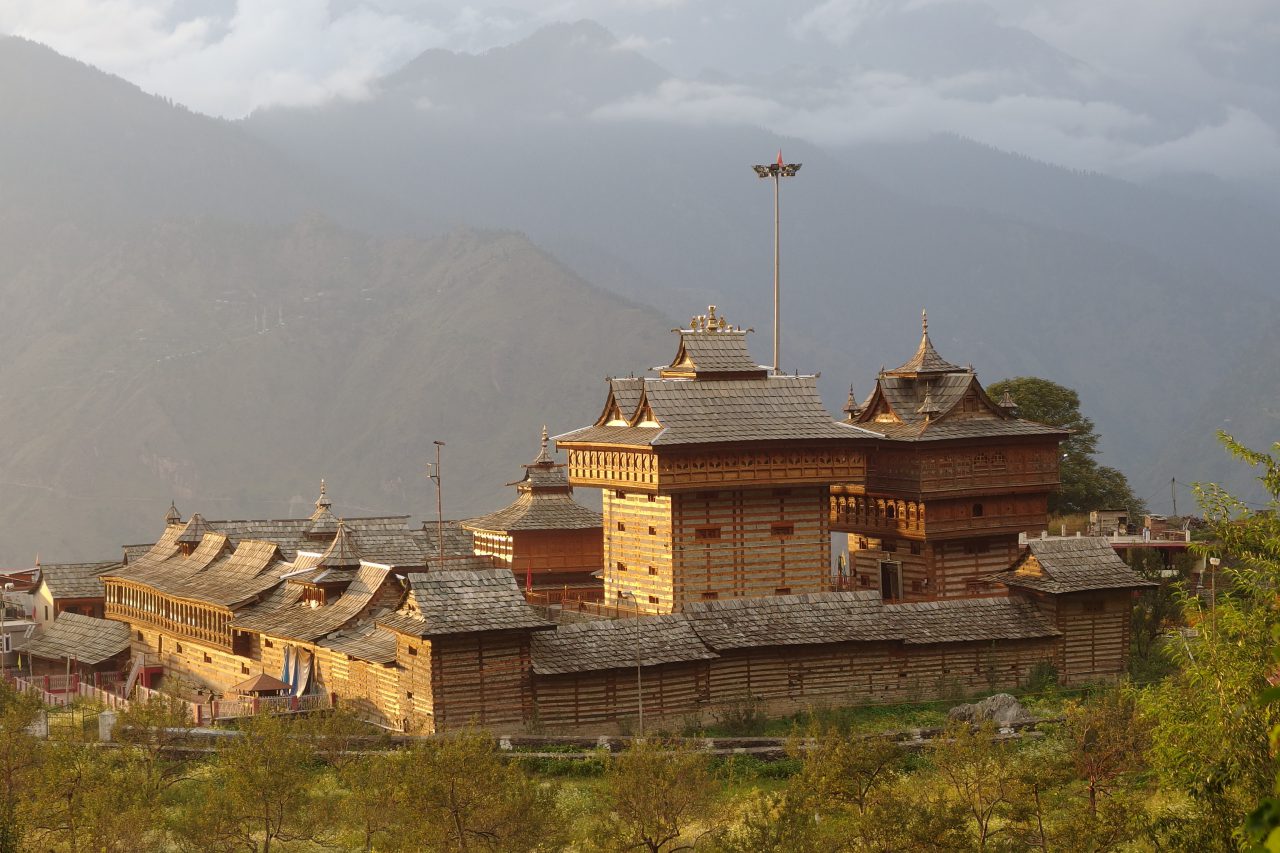

While this one volume was all the information I had on the area before my visit, once I arrived I found a structure that was even bigger than I expected. It felt like nothing I had ever seen before as it stood tall inside the quiet mountain village.

-

An Evening View of Bhimakali Temple

The temple has two main towers that were apparently built at different times, its goddess enshrined in the shorter of the two. It is notable for its construction, with walls created using alternating layers of rock and wood (Himalayan cedar). This was different from any kind of architecture I had ever seen before, and its style fascinated me.

When I looked closer, I saw that the corners and central areas use two layers of wood, creating a grid that contains stone in its holes. Could this be the result of local wisdom in a seismically active area? The upper part of the tower is made of wood that grows out from the wall, creating a rectangular and overhanging terrace-like area. This overhanging external wall is light and surrounded by planks, like a curtain wall. Both the tower’s roof as well as the roofs of the surrounding rooms are made entirely of slate.

-

Looking Up at Bhimakali Temple’s Tower

While the old homes I visited in the village were built on a different scale, they are made in nearly an identical way to the temple. They have cores consisting of alternating layers of wood framing and stone, while their second floors are overhanging, open-air terraces. These second floors act as main living spaces, while the first floors seem to be used for storage.

-

A home built the same way as the temple. Its second floor is a living area.

As these core sections have barely any windows aside from their entrances, they are cavernously dark on the inside, perhaps because they are located in a cold region.

Looking at the back facade of the home I visited, I saw small amounts of window frame-like lumber inserted inside gaps between layers of wood, and I discovered even smaller home windows created inside of these. After all, these uniquely constructed walls seem to make creating windows a difficult task.

-

Small home windows opened inside the wood inserted into the wall.

The rooms surrounding Bhimakali Temple’s towers are no exception to this method of construction. Their walls also contain only small little windows, or really just holes that have been bored there.

-

The wall of one of the many rooms surrounding the Temple’s towers. The small holes are apparently windows.

But looking at the neighboring buildings, I could see similar overhanging areas. Just like the temple, they are surrounded by planks, like curtain walls, and contain ribbon windows that remind me of Japanese or modern architecture.

-

Small built-in windows and larger windows in overhanging sections

While windows could barely be created in the built-in areas, these ribbon windows seem free as they stand in contrast. Their window frames are carved and covered in embellishments, as if to celebrate this freedom. If anything, the function of these small built-in windows seems to be not to provide light or air, but instead to accentuate the free windows that overhang them, there only to establish a kind of rhythm.

As I wandered around the temple, a tourist who said he was in the field of architecture came up and talked to me. According to him, there were many old structures still standing in a village farther past this one, close to the Tibetan border. The next morning, I boarded a bus heading even deeper into the region. It seemed like my trip to Kinnaur district was going to take longer than I first thought.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Tokyo in 1992. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In 2017 he graduated from Waseda Universityʼs Nakatani Norihito Lab with his masterʼs in architectural history. His dissertation received the Sanae Award. From May on, he has been working under Huang Sheng-Yuan at Fieldoffice Architects, in Yilan County, Taiwan.