Series Traveling Asia through a Window

A Desert below Sea Level — Turpan, Part 3

19 Apr 2017

What I learned from these grape-drying huts was that the key to a dwelling in a desert below sea level was creating shadows by bricks, poplar, and a few branches and leaves as well as ventilating the room.

I visited seven Uyghur settlements while in Turpan. I have marked the locations of six out of those seven settlements and the aforementioned grape-drying huts in the map below. It seemed as if there were many people from the Han clan located in the center of the city adorned with grid-like wide roads while the Uyghur settlements were located in the surrounding green areas.

-

Locations of the houses visited (Plotted by the author on Google Earth)

The first thing about the Uyghur settlements that surprised me was their vast exterior. In summertime, occupations of the settlement put a large bed on their patio and sleep on it. On the patio were shadows created by grapevine roofs, offering up a rather comfortable space. It reminded me of my accommodation: the dwelling was renovated from a Uyghur-style house. Lacking an air conditioner, it was so hot at midnight I went out to patio where I could sleep much more comfortably. I understood the “Uyghur space” from experience.

-

The patio of a Uyghur settlement. A huge bed on a carpet serves as their main living space during summer.

They sleep outside during summer, but that’s not possible during cold winter. Normally, a robust brick house is built next to open patio. The house is shelter-like space with only a little opening and seems rarely used during summer.

They cool themselves in an airy, shadowy space resembling grape-drying huts during the summer and fight the cold weather inside the bricks during the winter. In other words, wisdom for everyday life dictates that one must migrate within their property in accordance with the seasons. Therefore the inner space (brick house) and the outer space (patio) coexist in equal proportion within the property, and that constitutes a basic form of the Uyghur settlements.

As can be seen in the photos below, some patios have a robust roof covering them. As for the pillars supporting the roof, today they have been replaced by a single steel one. With the exception of a few added modern materials that did not exist in the land, the inhabitants of the Uygur settlements have not changed the basic form of their dwelling. This is proof that such a form suits the land they live in.

-

A patio surrounded by a robust brick hut

However, if you build a patio surrounded by bricks you can protect your privacy but light and air become scant. If you look closely, you can see pockets of gapped brick at the top of the walls touching the roof. Though it may look like a series of patterns, it is actually a window meant to usher in light and air.

Later, I visited the village of Piqan, not far from Turpan. There I realized the importance of these mysterious pockets of gapped brick.

While watching from the entrance of their patio two older men and a boy drinking tea, they invited me in. They greeted me with the traditional Muslim greeting, assalamu alaikum. One of the men offered me naan-like hard bread and tea, and the elementary school boy showed around their home.

-

A view into the patio. The roof seems to be lifted.

Perhaps a result of the sands traveling by wind from the nearby desert, this house, too, had created an enclosed patio. Here, too, we see gaps just below its roof. As a result of these gaps the roof appears to be lifted; they also draw in light and air. The gaps also soften direct sunlight, serving as a cushion against the strong sun.

Thanks to boy’s guidance I could climb up the roof. The lifted roof looks like this from outside.

-

The structure of the lifted roof

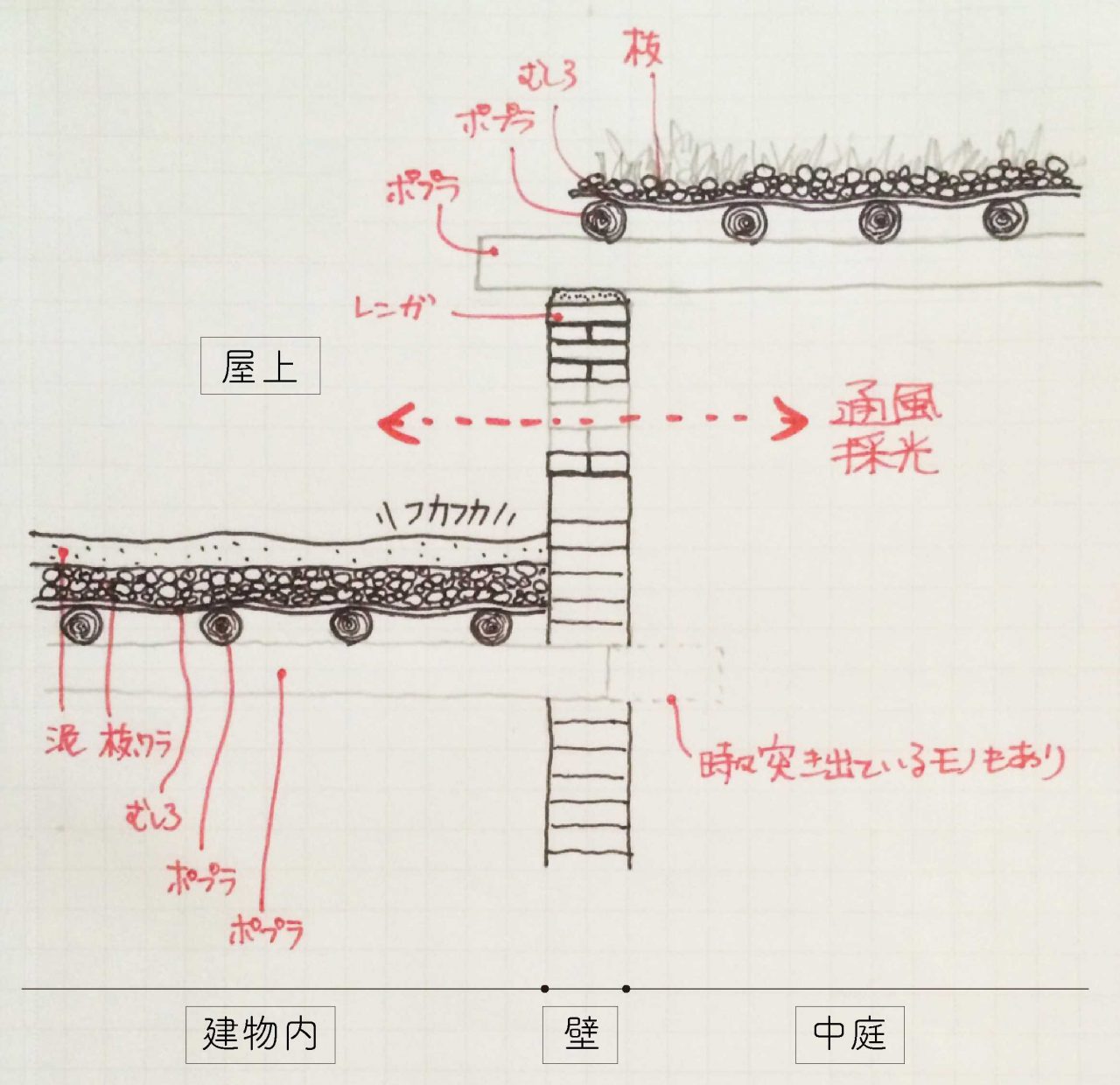

A double-opening has been created as if drawing patterns while a straw-like roof made of poplar and leaves has been placed onto it.

This opening is their most inventive architectural device, I thought to myself. With excitement I started to write a partial detail drawing, and the boy looked curiously at this strange Oriental man.

-

A partial detail drawing of the lifted roof (drawn by the author)

Looking around, I realized that surrounding houses also had their own brand of lifted roofs. About 5m above their living space was a vast world of light and wind. The lifted roof is a small but great invention that makes an unforgiving nature more amenable to a human living environment.

-

This roof is lifted by placing iron joists on bricks.

-

This roof is lifted only by blocks of bricks.

-

A roof of unenclosed patio can be lifted as well.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Shizuoka prefecture in 1992 and grew up in Tokyo. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. From April 2014 he began life as a graduate student in architectural history, studying under Norihito Nakatani. In June of 2014 he proposed a restoration plan for residents of Izu Ōshima for a sediment-related disaster. This would become his graduation project. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In Yilan County,Taiwan, he worked as an intern at Fieldoffice Architects.