Series Traveling Asia through a Window

Houses beyond the Places of Scenic Beauty (2)

08 Nov 2016

Repeating myself the phrase “your house” in Chinese, the old man and I walked for about 40 minutes through a town located outside of the scenic area. I saw a construction site for some new, large building and walked along unpaved narrow streets; I saw scenes from daily live different from tourist sites. We finally arrived at what seemed to be the old man’s home. (Only later did I realize I had mistaken the phrase “your house” all along.)

The house was a closed-off, flat building with walls of painted white brick. The tiles of the roof was similar to the ones I saw in the scenic area, and upon closer inspection, the manner in which they were stacked also looked alike. Despite being located outside of the scenic area it seemed they had something in common. Nearby there were numerous buildings of a similar fashion, as if many of the buildings were constructed in one shot.

-

The old man’s home (front)

Upon entering the home, there was no equivalent to the entrance of a Japanese home where one removes their shoes. Instead, it was a space consisting of a dirt floor. As someone used to Japanese houses, it does not feel like a home. An older woman I imagine to be his wife was cozily sitting in a chair made of bamboo and cane. Although somewhat puzzled by this young foreigner, she looked curiously at my Chinese conversation book and sketches contained in my notebook; she even spoke to me in Chinese. Of course I did not understand what she was saying, but my visit did not seem to bother her. That was my first time visiting a stranger’s house in a foreign land. With their consent I measured their house.

-

The living room just in front of the entrance. His wife sitting in a chair made of bamboo and cane.

-

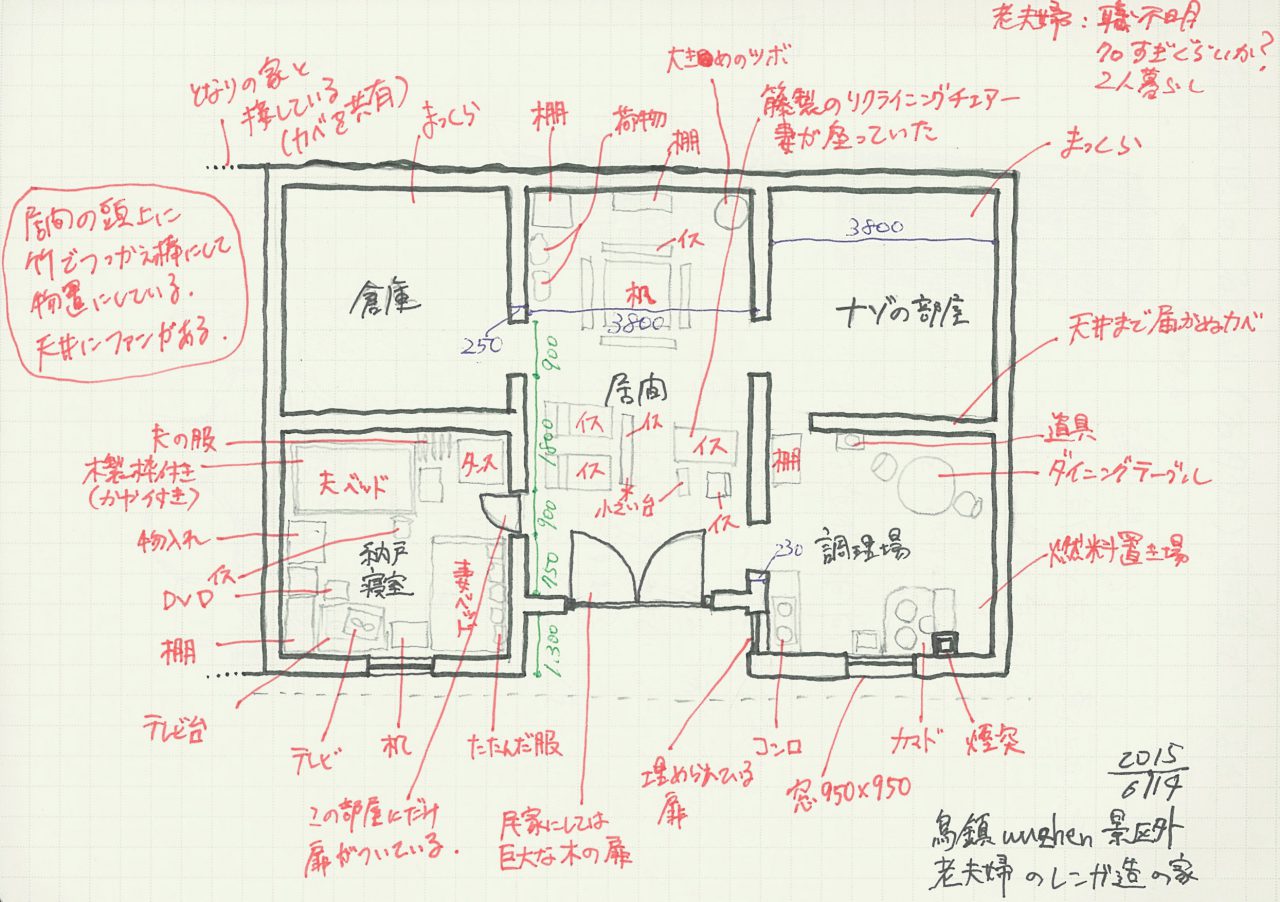

A measured drawing of their house. A symmetrical home with the living room at the center.

Inside the house, rooms are distributed symmetrically with the living room at the center. With only an entrance door and two windows at the front, it was quite dark inside. The backroom seemed to be used as a storage room while the living room, kitchen, and the bedroom, seemed to be used daily. It was an extremely simple home.

A window just to the side of a furnace in the kitchen was also simple, with bars attached to it for seemingly security purposes. The decorated wooden windows and doors I saw in the scenic area were nowhere to be found. It seemed functionality was prioritized. Within the dark kitchen, the furnace and sink are bathed in streaks of light.

-

Within the dark kitchen living spaces are created around streaks of light.

I was surprised when turning around to face the entrance I had come in from. Compared to the windows found in their rooms, there was a large, almost excessive heavy wooden door like the one seen in temples. This tells me the most important part of this house is its entrance.

-

The wooden door has a strong presence. This is not a temple but a small, flat house.

Though lacking a decorated framework, the door obviously has a significance different from the merely functional windows.

Surprisingly, they showed me their bedroom as well. Inside the room there were various items such as clothes, a TV, a closet, and boxes full of things. Everything was neatly arranged. The space itself seemed to say that “all things of importance are located here.” The entrance to the room is also made of wood, and it can be locked up tightly. Among the four rooms connected to the living room only this bedroom has such a heavy door. A wooden door in the backroom is left open, and the kitchen and storage room do not have one.

The houses outside of the scenic area might have been built in one shot; they were all very simple in nature. They are not meant to be seen by tourists, and even if a tourist walks past it while in the district they would probably overlook them. But for those living in them, there is a conscious desire to mark it as an important place by adorning openings like windows or entrances with a heavy wooden door, a practice reminiscent of the wooden furnishings seen within the scenic area.

-

Light rushing in from the huge door brightens the couple’s living room. The wooden door serving as entrance to the bedroom can be seen on the right side.

After having expressed my gratitude and leaving their house, they saw me off from the big entrance with a smile.

-

The old man and his wife see me off from within the large entrance to their home.

Ryuki Taguma

Taguma was born in Shizuoka prefecture in 1992 and grew up in Tokyo. In 2014, he graduated from the Department of Architecture (Creative Science and Engineering) of Waseda University. He received a gold medal for his graduation project in architecture and received top recognition for his graduation thesis. From April 2014 he began life as a graduate student in architectural history, studying under Norihito Nakatani. In June of 2014 he proposed a restoration plan for residents of Izu Ōshima for a sediment-related disaster. This would become his graduation project. In 2015 he took a year off from school to travel around villages and folk houses in 11 countries in Asia and the Middle East, visiting countries from China to Israel. In Yilan County,Taiwan, he worked as an intern at Fieldoffice Architects.