Chapter 2: The frame – the window as optical device or trompe l’oeil from Mantegna to Ryan Gander

03 Feb 2020

Whether facing outwards to the world or inwards to the self, an artist is often restrained by the framing device of the window—unable to break free from a rectilinear box or blank surface that demands to be filled, but which can never contain the sheer volume of possibilities and countless multitudes of our cosmos. Indeed, as an aperture, the window, canvas or blank sheet of paper is but a tiny fraction of the whole, representing only a glimpse of our visible reality. While this narrow view might contend that a window or a work of art is a necessarily compromised and merely partial inlet or outlet, it is equally true that much of our life is now increasingly being mediated by these rectilinear boundaries – whether through a television screen, a page, a photograph or a handheld phone or tablet. Rather than permitting only a restricted field of vision, these windows could be seen as magical portals to other universes or even just uncanny and lifelike portrayals of experience.

Accuracy was one of the first and foremost forms of pictorial magic performed by artists, with two early Greek painters, Zeuxis and Parrhasius competing to see whose picture could better fool the eye in an account recorded by Pliny the Elder. Zeuxis painted a bunch of grapes so compelling that birds came down to feast on them. Parrhasius congratulated his opponent and beckoned him to see his work behind a curtain, only for Zeuxis to find that the curtain was the painting.

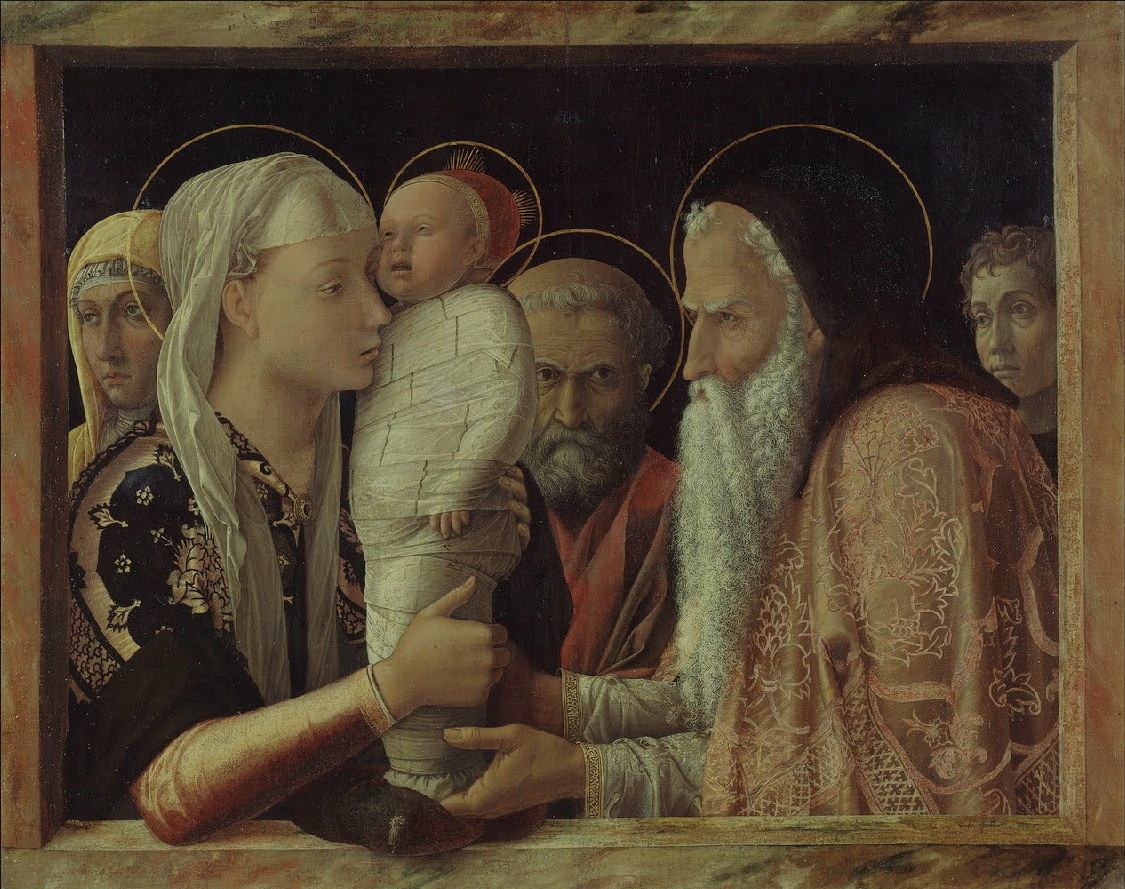

Perhaps something similar occurs in a painting by Andrea Mantegna, The Presentation of Christ in the Temple (1454). The figures crowd in front of the unknowable, inky background behind, drawn together by a tight composition and a marble window niche that encapsulates the entire scene. Sculptural robes also attempt to heighten the three-dimensionality provided by the Virgin Mary’s elbow jutting out into our space, but these were the very earliest days of the Renaissance, so graphic haloes, embroidered patterns and stiff portraits still persist. In fact, this may be the very first instance of a frame within a frame being used by an artist to break out of the picture plane in order to add perspective and depth to an otherwise two-dimensional gathering.

-

Andrea Mantegna, The Presentation of Christ in the Temple, 1454, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin.

While Mantegna used the window’s proximity to the viewer to match the thrusting action of the proffering of the child, there are other moments when the frame keeps us at bay. In Titian’s Portrait of Gerolamo Barbarigo (also known as Man with a Quilted Sleeve, 1510), a noble gentleman leans onto a windowsill in an archetypal over-the-shoulder portrait—known as ʻdi spallo’ in Italian. His slightly lofty position, looking down on us on the ʻstreet’ side, is perhaps an indicator of his status. It was both the subject and the product of a young, ambitious and confident painter – some have intimated an element of self-portraiture, although Titian was still only in his early 20’s when he painted this – but either way, the sitter looks on in our direction with some disdain, suggesting that only he is capable of breaking the barrier between us. The artist also exercises his will in the picture by including his scratched initials T.V. (Tiziano Vecellio) in the frame of the supporting wall, in an act of signature and ownership over the image.

-

Titian, Portrait of Gerolamo Barbarigo, 1510, National Gallery, London.

Another framed and signed ledge appears in Still Life with Game, Vegetables and Fruit (1602), by a Spanish artist called Juan Sánchez Cotán of the overflowing contents of a supply cupboard: a number of birds including goldfinches, sparrows and partridges, as well as apples, carrots, lemons, radishes, and a large bunch of white celery. This use of an architectural frame is almost photographic, with the bright glare of light reflecting off the objects in this scene, linking the painting to the style of trompe l’oeil illusionism that would become popular in Dutch still life paintings of this era. Cotán was rather a practicing monk and a master of the bodegón, the particularly Spanish school of still life painting emphasised the daily rituals of hunting, eating and drinking (coming from the Spanish word for ʻtavern’). Considered by many to be a lowly genre of painting, it grew more powerful through its metaphorical ability to remind the viewer of their mortality and the transience of human existence. Here the evidence of memento mori are the dead game birds and the blackness of the void behind, which suggest the nothingness awaiting us in the afterlife, or at the very least, a tender balance between the produce in the foreground, resting on a thin line between life and death.

-

Juan Sánchez Cotán, Still Life with Game, Vegetables and Fruit, 1602, Museo del Prado, Madrid

Although mere verisimilitude – or the copying of nature and the creation of a deception worthy of a camera—was the goal of many artists of the past, the use of a theatrical framing device, such as a window or door frame, would always elevate a picture from paying mere lip service to its subject matter, towards the higher trickery of involving the audience in an interactive, visceral embodiment of what was being depicted. One exuberant example of this is the young boy seen leaping out of another Spanish painting, by the little-known Pere Borrell y del Caso, who seems to be attempting to break free from the very picture that binds him. The rendering of the picture frame produces a comic moment of double-take, furthered by the humorous title, Escaping from the Critics (1874), which most likely referred to the scornful reaction that the artist’s conservative peers would have to this boundary-breaking work.

-

Pere Borrell y del Caso, Escaping from the Critics, 1874, Banco de España Collection, Madrid.

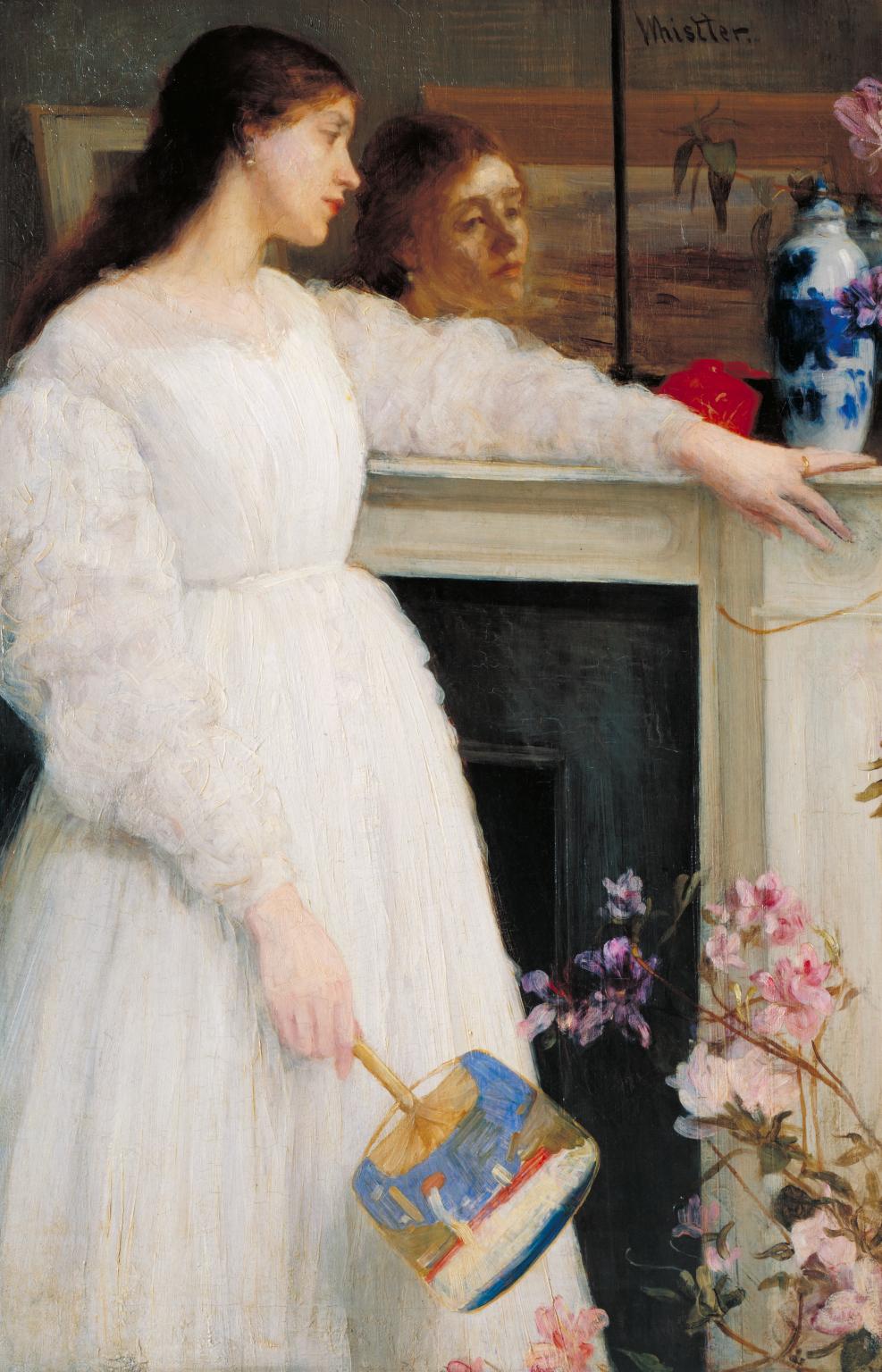

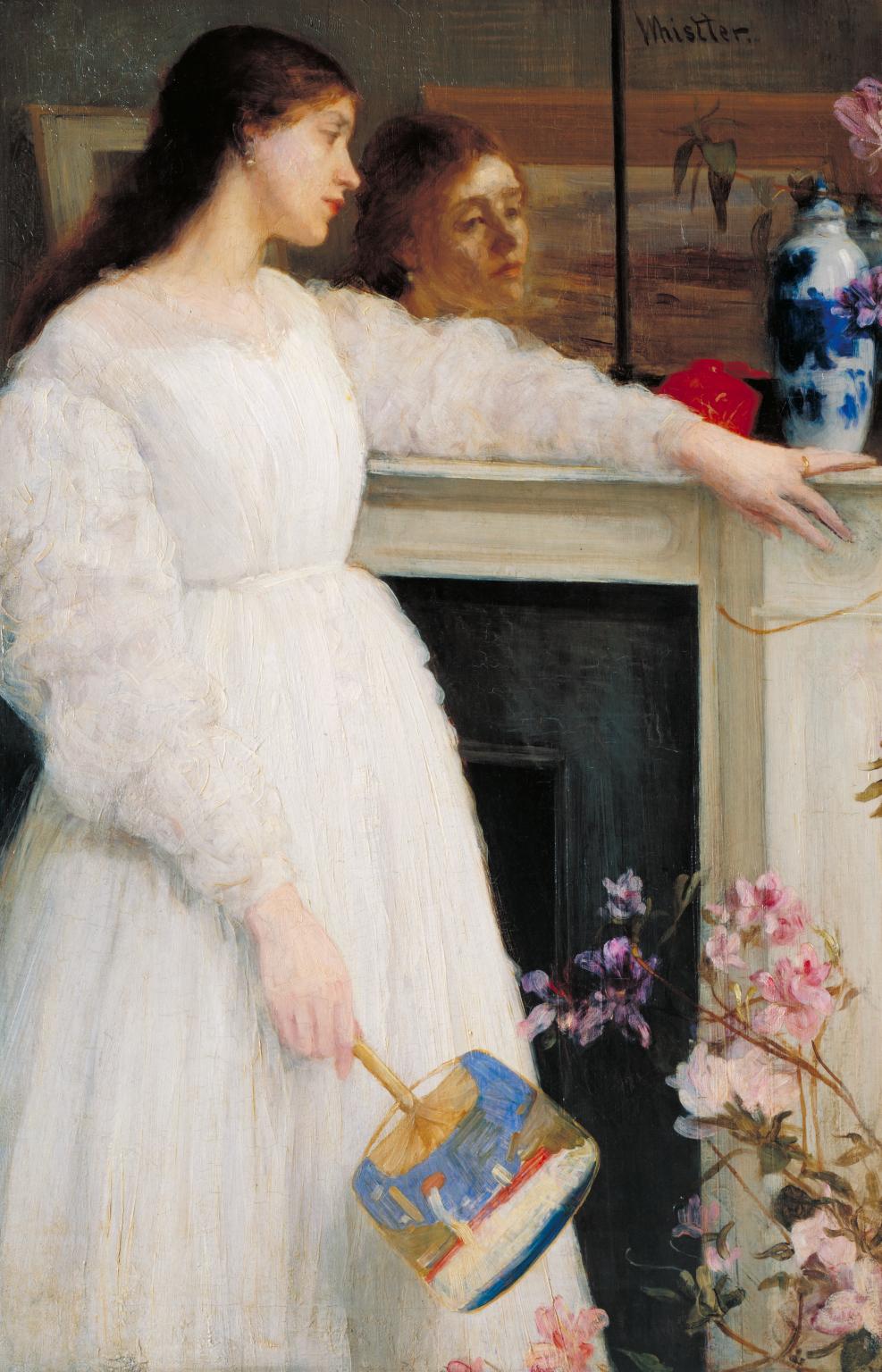

At around the same time, James Whistler painted a similarly arresting image, entitled Symphony in White, No. 2: The Little White Girl (1864). Here the mirror acts as a picture frame, allowing a wistful figure to gaze out at us from a reflection, which allows us to glimpse her without her knowing. The poet Algernon Swinburne composed a poem about this work called Before the Mirror (1866), which included the line:

Deep in the gleaming glass

She sees all past things pass,

And all sweet life that was lie down and lie.

Whistler so enjoyed this verse that he printed a version on gold paper and pinned it to the painting’s frame, as a complementary work, rather than as a description or caption. This detail furthers the picture’s credentials as an immersive painting, with the potential to either burst out of its two dimensions or to drag us into another world behind the canvas.

-

James Whistler, Symphony in White, No. 2: The Little White Girl, 1864, Tate Gallery, London.

We are now used to actors, performers and filmmakers rupturing the so-called ʻfourth wall’, or using direct address to better link expression and experience. Yet the hallowed frame of the painting was an earlier means of involving or startling the spectator and none was more spectacular than David Teniers’ documentation of one of the greatest collections of Old Masters ever amassed. The Gallery of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm in Brussels (1651) is one of a number of attempts to document this impressive array of pictures by Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese and others, of which Teniers was essentially the curator, although at least one of his own paintings was in the collection too. Not only do these frames each contain its own masterpiece – a Madonna of the Cherries, Cain killing Abel, a Lady with an Ermine, an Allegory of Spring and so on – allowing the artist to show off both his skills and the great patronage on display, but they all open a window to an alternate landscape, an individual artistic vision and a new universe to explore.

-

David Teniers, The Gallery of Archduke Leopold in Brusselsbetween, 1651, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

With the advent of modern art, however, the pictorial frame was reduced to a simple black or white square and the picture plane was no longer a sacrosanct stage for the play of objects or visual phenomena. Juan Gris and the other Cubists dispensed with recognisable space entirely, exploding the linear perspective achieved over two millennia of cultural progress. In The Open Window (1921), Gris compounds interior and exterior views into one, collapsing the window or frame motif into a free-flowing aperture of spatial disorientation.

-

Juan Gris, Open Window, 1921, Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid.

Even more radical was Marcel Duchamp’s usage of the found object or ready-made sculptural object, although for his blacked-out pair of French windows, an additional jolt comes from the punning title of Fresh Widow (1920). Indeed it was said that Duchamp hoped this work might showcase his skills as a ʻfenêtrier’, not as a window-maker exactly, but as someone ʻconcerned with the possible developments that a window might u

-

Marcel Duchamp, Fresh Widow, 1920, Vera & Arturo Schwarz Collection of Dada and Surrealist Art, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. © Association Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris & JASPAR, Tokyo, 2020 G2112

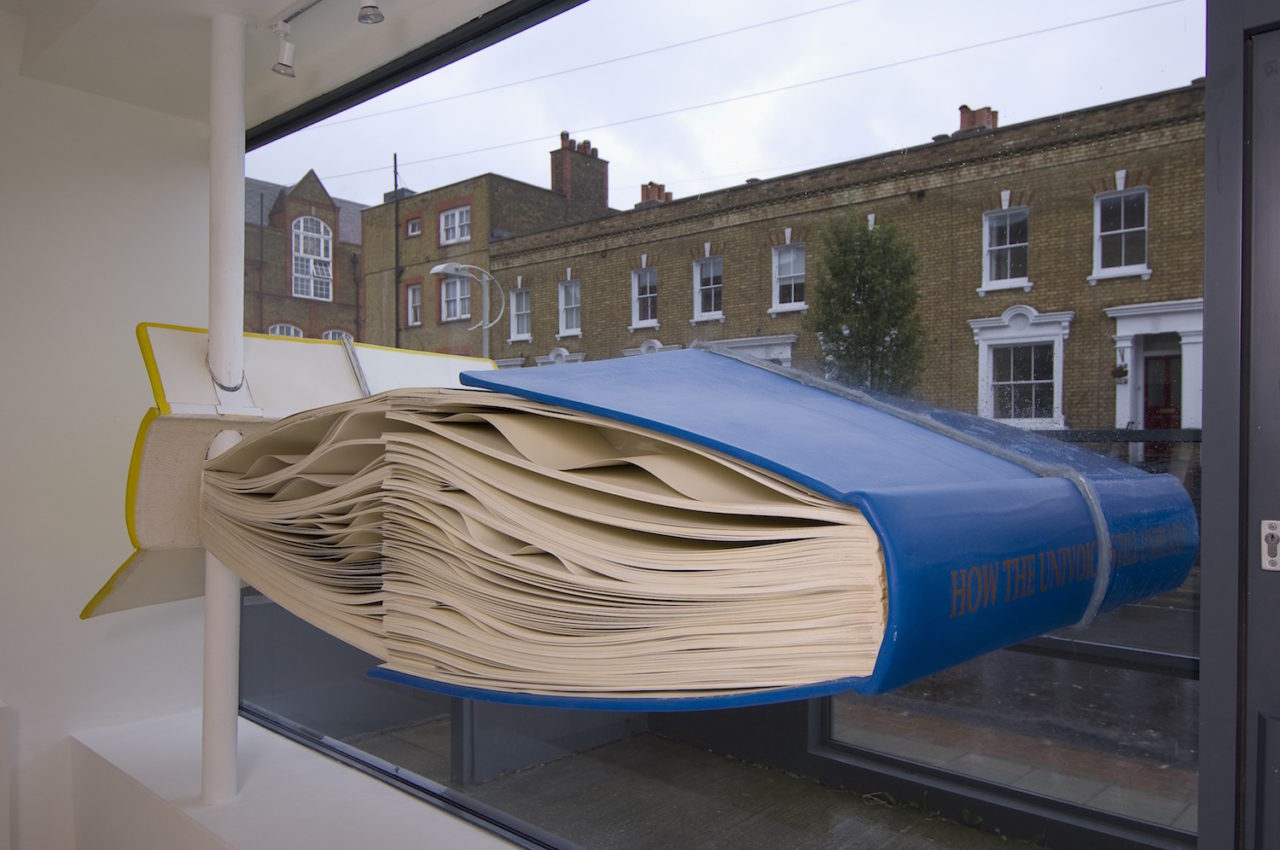

This expanded notion of what a work of art could encompass spatially is further explored by the artist John Latham who created not only numerous Canvas Events (1994-95), in which the surface of his unprimed painting supports were sprayed and twisted into semi-sculptural, de-materialised objects, as well as various Roller Paintings (1964), in which unprimed canvas would be painted and then motorized to mirror the function of a window blind, but who also embedded a giant, cantilevered book into the facade of his studio and home, creating a liminal frontier between the outside world and his work. Indeed, he titled different elements of his live/work installation The Face of Flat Time House (2008), The Face (for the frontage), The Mind, The Brain (thinking or library spaces), The Hand (the studio) and The Body (the other areas for sitting, lying, sleeping and so on).

-

John Latham, Canvas Event, 1994–95. Acrylic on canvas, 122 x 91.2 cm, 48 x 35 7/8 in ( LATH940007) © The John Latham Foundation; Courtesy Lisson Gallery. Photography by Ken Adlard.

-

John Latham, Untitled (Roller Painting), 1964. Exhibition: John Latham: Spray Paintings 1 April – 7 May 2016, Lisson Gallery London. © The John Latham Foundation; Courtesy Lisson Gallery. Photography by Jack Hems.

-

John Latham, The Face of Flat Time House, 2008, Flat Time House, London. © The John Latham Foundation; Courtesy Flat Time House.

Another artist that works with Lisson Gallery, Ryan Gander has made moving portraits of the window in his own workspace, including such as View from the Studio Window (28th February 2018), which reveals a hazy rendering of the view outside as it transitions from day to night throughout a 24-hour cycle. The animated screens behind the frosted glass approximate the exact light conditions and changing weather of that time and place – not to mention the gently swaying silhouettes of trees and the shadow of a chain link fence. Here the frame is both denied and reinforced, the window leads nowhere and yet accurately represents the reality – the window is now digital, not analogue.

Finch, like Friedrich or Van Gogh, has created an intimate, atmospheric window into the artist’s studio practice while inviting viewers to become active participants of the memory of that moment, rather than mere passive admirers.

-

Ryan Gander, View from the Studio Window (28th February 2018) Daytime detail. HD screens, PC, plywood, steel, acrylic, window frosting, paint, window fixtures, 122.5 x 145.9 x 33 cm, 48 1/8 x 57 3/8 x 12 7/8 in

(GAND180033)

-

Ryan Gander, View from the Studio Window (28th February 2018) Night-time detail. HD screens, PC, plywood, steel, acrylic, window frosting, paint, window fixtures, 122.5 x 145.9 x 33 cm, 48 1/8 x 57 3/8 x 12 7/8 in

(GAND180033)

Ossian Ward

Content Director at Lisson Gallery (London/New York/Shanghai) and a writer on contemporary art. As well as leading the gallery’s communications and publishing teams he was co-curator of the major off-site exhibition, ‘Everything at Once’ and editor of the gallery’s 50th anniversary book, ‘ARTIST | WORK | LISSON’ (both 2017). Until 2013, he was the chief art critic and Visual Arts Editor at Time Out London for over six years and has contributed to magazines such as Art in America, Art + Auction, World of Interiors, Esquire, The News Statesman and Wallpaper, as well as newspapers including the Evening Standard, The Guardian, the Observer, The Times and The Independent on Sunday. Formerly editor of ArtReview and the V&A Magazine, he has also worked at The Art Newspaper and edited a biennial publication, The Artists’ Yearbook, for Thames & Hudson from 2005-2010. His book, titled Ways of Looking: How to Experience Contemporary Art was published by Laurence King in 2014. A sequel, Look Again: How to Experience the Old Masters will be published by Thames & Hudson in 2019.