A Home that Draws in Breezes from All Directions: The Fumiko Hayashi House

19 Mar 2025

Fumiko Hayashi (1903–1951), a prominent Showa era writer, established a new residence in Shimoochiai (present-day Nakai), Tokyo, in 1941, amid a time of war. While commissioning the project to architect Bunzo Yamaguchi, she actively involved herself in its design, consulting numerous books and even traveling to Kyoto to gather inspiration from precedents. Designed with a primary focus on ventilation, the house features meticulously thought-out windows, speaking to Fumiko’s keen interest in the setup of her living environment.

Waking up in the morning, I feel an urge to immediately open a window to let in the fresh air. When it is sunny out, I find myself wanting to open all the windows in my home to allow the breeze to flow throughout. The idea that a well-designed house should facilitate the free passage of breezes through its interiors is ingrained in us in Japan. The writer Fumiko Hayashi also believed this when building her home, asserting, “it is crucial to draw in breezes from all directions in a climate like that of Japan’s”.1 Renowned for works like Diary of a Vagabond (Hōrōki), she undoubtedly was brimming with ideas for how to create a comfortable home, having experienced diverse climates through her travels and upbringing. Completed in 1941, when she was 37, her Shimoochiai residence is a well-ventilated Japanese-style house consisting of a main house and an annex that are arranged linearly in the east-west direction.

Born in Moji, Fukuoka, Fumiko hopped from place to place in Kyushu with her peddler mother and stepfather before setting off on her own to Tokyo at the age of 19. There, she worked a variety of jobs to sustain herself while aspiring to a literary career. She achieved recognition with Diary of a Vagabond, penned at 25. In November 1931, at 27, she journeyed to Europe, where she primarily resided in Paris and London before returning to Japan the following June. It was during her sojourn in Paris that she had her famous encounter with the architect Seiichi Shirai, who was studying in Berlin at the time.

-

View from the garden, looking through the bedroom, the anteroom, and into the study.

After returning to Japan, Fumiko rented a Western-style house in Shimoochiai, where she lived for about nine years. However, she apparently never felt at home in the house, which novelist Masuji Ibuse describes as resembling “a colonial consulate building”, and she also later affirms, “I truly loathe Western-style houses”.2 Her experiences in Europe had triggered within her a re-embracing of things Japanese: “A comfortable home has no need for luxuries of any sort. After returning from Paris, I started to reconsider the merit of small Japanese houses, realizing that the essence of a home lies not in how others see it but in how comfortable it is for one to live in”.3 Incidentally, the novelist Nobuko Yoshiya, who had also been living in Europe around the same time as Fumiko, built herself an Isoya Yoshida-designed sukiya-style house in Ushigome, Tokyo, in 1936. Fumiko was acquainted with Yoshiya, who was already a popular author and had also lived in Shimoochiai for a time.

-

View from the living room, looking towards the bedroom beyond the courtyard.

When the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out, Fumiko’s work as a war correspondent took her to places such as Shanghai and Nanjing. It was during this war, in 1939, that she purchased the land to build her new residence in Shimoochiai. The architect she hired for the project was not Yoshida, but Bunzo Yamaguchi, who had also been staying in Europe around the same time as her. However, she and her husband, the painter Ryokubin Tezuka, did visit the Yoshiya House in Ushigome, possibly to take notes from it.4

-

The windows of the main house’s washroom and bathroom face the courtyard.

A Nonhierarchical Collage-Like Plan

The house was initially envisioned as a single structure, but because the wartime restrictions limited the floor area of new buildings to 30.25 tsubo [approx. 100 square meters], the plans were revised to construct two structures side by side, one in Fumiko’s name and the other in Tezuka’s. The main house (east building) has on its south end a garden-side hiroen [wide veranda], a living room, and a small room protruding into the garden; a maids’ room and kitchen on its north end; and a bathroom and washroom on its west end. The drawing room, usually located on the south end, has been placed in the northeast corner, breaking from the traditional ceremonious housing plan rooted in patriarchal norms. The annex (west building) contains the bedroom, Fumiko’s study, and Tezuka’s atelier. The study was originally where the bedroom now is, but Fumiko seemed to have found it too bright, as she soon moved it into the former storage room in the center of the building. As the annex does not have a formal entrance, it was accessed from the main house using the anteroom’s sliding glass doors near the doma [unfloored transitional space].

-

The yukimishōji of the study.

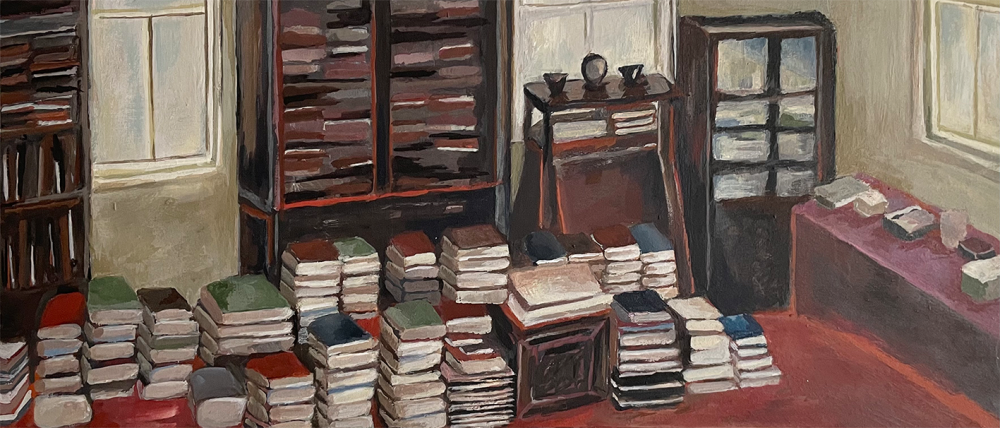

In 1928, when Yamaguchi was an employee at the firm of Kikuji Ishimoto, he designed a house for another author, Yasuko Miyake, but it was a white modernist-style house. Fumiko and Yamaguchi evidently knew each other before they went to Europe,5 and she may have been drawn to work with him because she felt an affinity for his background as a son of generational carpenters, which set him apart from the so-called elites. Though she explains that her role in the project was limited to “mostly just asking the architect for his opinion to learn good ideas”,6 she also writes, “when building a home, it feels somewhat wrong to merely live in it while entrusting its design entirely to others”.7 She actively involved herself in the design, consulting nearly 200 books in the process.

-

View of the garden from the bedroom.

The Shinjuku Historical Museum’s collection of Fumiko’s library includes a number of books related to housing.8 Images of features she liked are annotated in red pencil with notes such as “reference for tobukuro [storage box for storm shutters] and takeen [bamboo platforms]”, “reference for elderly room”, “reference for walls”, “reference for fusuma [sliding partitions]”, “reference for annex anteroom fusuma”, and “reference for study”. One can see that these features were indeed referenced. For example, the shōji [translucent screens] pictured in the exterior image of a tearoom of a Sutemi Horiguchi-designed house, annotated with the note “reference for shōji”, are similar to the shōji on the north side of the annex. The takeen in another image, marked with the note “tobukuro of main house living room corridor”, seems to have informed the one on the south side of the living room. Fumiko also spent about ten days touring Kyoto with the project architect, Katori, and the lead carpenter, Watanabe. During the trip, she encountered a taikobarishōji [screen faced with paper on both sides] in the kitchen of a sub-temple at the Byodoin in Uji, which inspired her to incorporate one on the north side of the annex.9

-

The takeen on the south side of the living room.

This house can be seen as a collage of sorts, owing to Fumiko’s idea to incorporate elements she liked from various houses and her nontraditional decision to spend money on the living room, bathroom, water closets, and kitchen, rather than on the drawing room. While the nonhierarchical plan centered on the living room and the generous proportions of the roofs indicate the involvement of an architect, Yamaguchi neither mentioned this house nor presented it as his work.

The Well-Thought-Out Fittings and Finishes

The meticulous attention given to the walls, ceilings, and fittings is evident throughout this house, which consists entirely of Japanese-style rooms, with the exception of the atelier. Of the doors and window fittings, which are mostly designed with traditional tatekōshido [vertical slat windows], yokokōshido [horizontal slat windows], and yukimishōji [lit. “snow-viewing shōji“; single-hung translucent screens], the most modern are the sliding glass doors along the hiroen of the main house. These doors, composed of large two-by-six-shaku [approx. 606-by-1,818-millimeter] panes of glass and a single vertical muntin, create an airy connection between the interior and the garden. The transom between the hiroen and living room features a shōjiranma [transom screen], which can be opened and closed to control ventilation. Every room, including the small room used by Fumiko’s mother and the drawing room used for meetings with editors, has openings in at least two directions, ensuring that there is a path for a cross-breeze.

-

The sliding glass doors of the hiroen open onto the south garden.

-

The living room connects to the small room via the hiroen.

The bedroom in the southeast corner of the annex is a well-lit sukiya-style space that has a distinctive railing along its courtyard-side window. The most notable feature of the annex, however, is the north corridor that links the anteroom and atelier. When the sliding amado [storm shutters] are drawn back, it becomes an open-air space with nothing enclosing it but a pair of taikobarishōji hanging down from the eaves. The takeen beside the corridor provides access to the water closet, and beyond it, a hand-wash basin is backdropped by the north garden. When inside the former storage room that Fumiko converted into her study, one can see this garden through a series of layered spaces articulated by a half-height doorway fitted with sliding shōji, the hanging taikobarishōji reminiscent of that at the Bosen tea room of the Kohoan sub-temple at Daitokuji, and the takeen. There is also a door built into the corridor’s leftmost amado, which allows one to access the water closet even when the house is shuttered at night.

-

View of the north garden from the study. The hanging taikobarishōji marks the boundary of the garden.

-

View of the study from the north garden. -

The built-in door of the amado.

The kitchen, bathroom, and maids’ room were of particular importance to Fumiko, and they, too, are designed with care. In the kitchen, a full-wall bay window positioned above the micro-terrazzo sink alleviates the darkness of the north-facing, four-tatami-mat-sized space, while the bathroom, finished with cypress panels and tile wainscoting, has a slender air vent integrated into the transom above its window. The washroom adjacent to the bathroom is designed as a continuation of the hiroen, enhancing its usefulness both for providing circulation and ventilation. The highlight is the maids’ room, where the window beside the bunkbed elegantly combines three different types of sliding window fittings (a tatekōshido, amado, and sliding frosted glass window). The room’s door to the corridor is also equipped with a ventilation grill.

-

The full-wall bay window of the north-facing kitchen.

-

The bathroom window with the air vent above.

-

The maids’ room window (kōshido and amado). -

The maids’ room window (sliding frosted glass window).

Fumiko did not particularly care about having an impressive tokobashira [ornamental alcove pillars] or using fancy wood. As reflected in her writing, her mind was instead entirely set on creating a home that would bring her joy: “I made use of a roll of yellow Hachijo fabric that I had bought a long time ago from a second-hand clothing store in Rogetsucho in Shiba to line the lower part of the fusuma in my room”.10 She also gave particular attention to surfaces that would come into contact with skin, such as the water closet floors, which she had finished with wood instead of tiles that would be cold on the feet. Looking at this building, one can appreciate very well how the physical experience of architecture is deeply related to not only scale and proportion but also the tactility of the materials and the movement of air. Fumiko, who passed away at the age of 47, spent the final decade of her life in this abode that she meticulously tailored to her heart’s desire. It is a sturdy and breezy home, complementary to the unpretentious lifestyle of its owner.

NOTES

1: Fumiko Hayashi, “Mukashi no ie” [Houses of old], Geijutsu shinchō [New Currents in Art] 1, no. 1 (January 1950). This article was written based on the findings of research funded by the 2005 Jusoken Research Grant, published as Atsuko Tanaka, Kiwa Matsushita, and Mari Akazawa, “A Study on Houses by Women Clients in the Interwar Japan: On the Modernization and Yearning for the Houses”, Journal of the Housing Research Foundation Jusoken, no. 48 (2021).

2: Fumiko Hayashi, “Utsukushii ie” [A beautiful house], Fujin no tame no nikki to zuihitsu [Diaries and Essays for Women] (Tokyo: Aiikusha, 1946), 123.

3: Hayashi, “Mukashi no ie”.

4: Nobuko Yoshiya, “Juntokuin Fuyō Seibi Daishi: Hayashi Fumiko to Watakushi” [Sister Fuyo Seibi of Juntokuin: Fumiko Hayashi and me], Jidenteki joryū bundanshi [An Autobiographical History of Women in Literature] (Tokyo: Kodansha, 2016).

5: Sadajiro Muramatsu, Nihon kenchikuka sanmyaku [The Lineal Mountain Ranges of Japan’s Architects] (Reprint, Tokyo: Kajima Institute Publishing, 2005), 219.

6: Hayashi, “Mukashi no ie”.

7: Hayashi, “Utsukushii ie”, 121.

8: They include the following: “Wafū shoheki shū” [Collection of Japanese-style walls], Kenchiku shashin ruiju [Architectural Photography Collection] 9, no. 14 (1935–1940); “Wayō zentei shū” [Collection of Japanese- and Western-style front gardens], Kenchiku shashin ruiju 9, no. 15 (1935–1940); “Jūtaku gaisō shū” [Collection of housing exteriors], Kenchiku shashin ruiju 10, no. 6 (1935–1940); “Shumi no sukiya jūtaku” [Tasteful sukiya-style houses], Kenchiku shashin ruiju 10, no. 8 (1938); “Chashitsu kenchiku dai 4” [Tea room architecture 4], Kenchiku shashin ruiju 10, no. 10 (1935–1940); “Wafū jūtaku no shitsunai kosei kan 3” [Interior composition of Japanese-style houses 3], Kenchiku shashin ruiju 10, no. 18; “Sukiyazukuri no jūtaku” [Sukiya-style houses], Kenchiku shashin ruiju, supplement; and “Tategu shashin shū kan 2” [Photography collection of doors and windows 2], Kenchiku shashin ruiju, supplement, no. 9 (1934). Published by Koyosha, Tokyo.

9: Hayashi, “Mukashi no ie”.

10: Hayashi, “Utsukushii ie”, 122.

Atsuko Tanaka

Born in Tokyo, Japan. Adjunct lecturer at Kanagawa University. Completed bachelor’s and master’s degrees in architecture at the Tokyo University of the Arts and a master’s degree at SCI-Arc. Holds a Doctor of Engineering. Having spent nine years in the US and Canada, her research has been focused on the history of architectural exchanges between Japan and the US, Japonism in architecture, and housing and women. Has taught as an assistant at the Tokyo University of the Arts (1991–93); an adjunct lecturer at the Nippon Institute of Technology, Tokyo Denki University, Musashi University, and Kanagawa University (2008–17); and as a specially appointed professor at the Shibaura Institute of Technology (2017–21). Major publications include Within White Boxes: The Architecture of Kameki Tsuchiura (Kajima Institute Publishing, 2014), Living in Great American Houses (Kenchiku Shiryo Kenkyusha, 2009), Biggu ritoru nobu: Raito no deshi josei kenchikuka Tsuchiura Nobuko [Big Little Nobu: Nobuko Tsuchiura, Female Architect and Disciple of Wright] (co-author; Domesu Publishers, 2001), and Amerika mokuzō kenchiku no tabi [A Journey to American Wooden Houses] (co-author; Maruzen Publishing, 1992).