Double Vision

06 Jul 2023

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Art

- Essays

Selecting “wallpaper” or organizing files on a “desktop” are now familiar acts that can either take place on our digital devices or in our living rooms. Through the screen’s interface, we gain access to a global network, a vast territory measured by pixels and bytes in the cloud, and materialized by poles and cables under the sea. Information across split screens and simultaneous browser windows emerges within a single frame and becomes tangible via haptic screen technology. Gestures such as a click, swipe, tap, or voice activation are required to engage with screens, eroding the distinction between material and immaterial spaces. Our eyes dart between architectural and virtual windows, whose material sensibilities have become indistinguishable.

Today’s rapid prototyping of new technologies furthers this blurring of windows and screens. Installed as a skylight, Mitsubishi’s Misola panel simulates daylight by programming alternating cool and warm projections. In a ceiling cavity of 120 millimeters, LEDs and light scattering devices embedded within a beveled frame produce a digital window, which can alleviate deep spaces without access to the exterior. Samsung’s The Frame TV, offered in a variety of wood finishes, also camouflages a screen in a window. When it detects movement, the television calibrates its visual effect to read as a matte board, mounting images that can be instantly uploaded from a virtual gallery. Transparent televisions like Panasonic and Vitra’s Vitrine have even explored how a screen and window can coexist within the same frame. When it is switched on, Vitrine displays media on a glass surface, and when it is off, it appears as a window frame displaced from the wall.

-

Daniel Rybakken for Panasonic, Vitrine, 2019

© Studio Daniel Rybakken

Misreading windows as screens, and screens as windows, suggests that the frame, or the boundary between what is physical and what is flattened, remains delicately intact. However, long before the advancement of screen technology, the ambiguity between windows and screens was described in various treatises and notes, as if foreshadowing what was to come. By tracing the historical overlap of screens and windows, we can re-imagine each as a mechanism beyond its physical form, ultimately representing a way of seeing.

Beginning with Alberti, De Pictura describes two drawing devices that relate a window and a screen: an “open window” and a “veil.” The first was used to delineate the edge of a painting, and the second, a grid-like netting stretched across a frame, mapped three-dimensional space to two-dimensional information. In her book The Virtual Window: From Alberti to Microsoft, Anne Friedberg argues that the “veil’s” lattice preceded digital bytes mapped onto the computer screen, leaving a profound cultural imprint.

While Alberti outlined these two interrelated techniques for painting, the “open window” and “veil” can be interpreted in architectural windows. For Robert Smithson, the provocative quality of a window can lie solely in its potential to be read as a screen. In his notes “Untitled (Air Terminal – Windows),” he defines windows as “simple grid systems that hold surfaces of transparent glass.” For Smithson, a window can transcend its banal, material components and instead be understood as a network of lines and surfaces. As if borrowing from Alberti’s “veil,” Smithson distills our vision through windows to a field of pixels dotting a screen.

The screen’s implicit organization of visual data had also been studied earlier in other mediums. Artists used the window as a portal to apply new notions of spatial order, which had already begun to disrupt familiar ways of interpreting information. In his painting The Telescope (1963), René Magritte interrogates how the elements that comprise a window are layered and reassembles them. A window left ajar peers into an opaque void, suggesting that the celestial view in front is in fact only an image illuminating the sill. Detached from the frame, the view glows on a screen that is no longer determined by its edge, peeling off into a dark abyss and concealing the inner componentry of the viewing device.

-

René Magritte, The Telescope (La lunette d’approche), 1963

Oil on canvas

69 5/16 × 45 1/4 in (176.1 × 114.9 cm)

The Menil Collection, Houston, Hickey-Robertson

© 2022 C. Herscovici / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

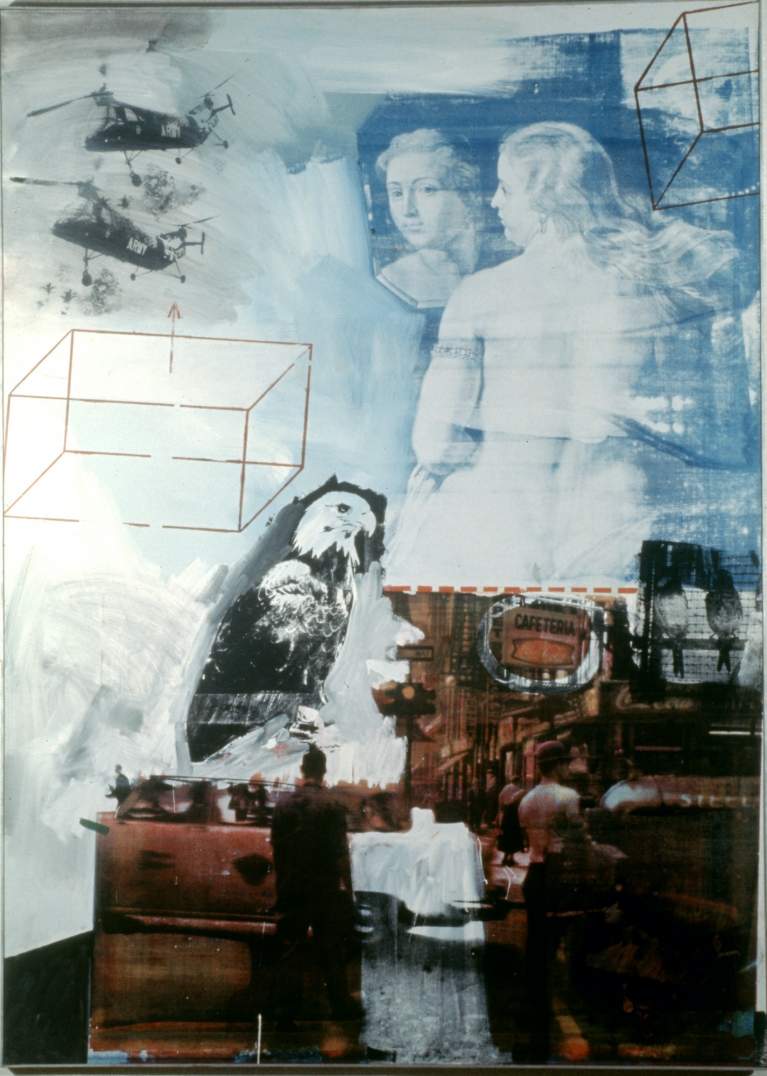

Combined on one canvas, these conflicting spatial hierarchies were not only expressed as the subject in works, but also in the techniques used to create them. Robert Rauschenberg made a series of paintings in the 1960s that experiments with layering and gives nuance to the relationship between windows and screens. These paintings use silk-screening, a process that recalls Alberti’s “veil” to transfer images from media by pressing ink through a textile screen, stretched across a frame. Historian Leo Steinberg has observed that these paintings presented a “flatbed picture plane,” or a conceptually new pictorial orientation that generates work as informational media. Rauschenberg crops images from newspapers and magazines, obscures perspectival sight lines, and rotates figures in parallel projection, as if drafted on a screen.

Steinberg writes that the paintings characterize an “irreducible flatness,” relentlessly committed to distorting depth across the canvas, thickened by discordant, fragmented imagery. Without relying on electronic instruments, these works harness the qualities of screens because of their detail and how various modes of representation are organized. The paintings give viewers a reading of space that oscillates between compression and expansion within a single picture plane. Steinberg’s “flatness” recalls “phenomenal transparency,” a condition addressed in Colin Rowe and Robert Slutzky’s seminal essay, “Transparency: Literal and Phenomenal.” When deep and shallow space confront one another in a composition, various interpretations cannot fully grasp the whole. Unable to release the tension, this produces an elusive affect, which can be observed in the built environment when windows (mis)behave as screens.

The way the frame is manipulated ultimately entangles windows and screens, producing a contemporary visuality that is deeply, superficially nuanced. Consider James Turrell’s Skyspace I (1974) in Varese, Italy, where he slices open the ceiling of a white room to provide a view of the sky above. Reducing the thickness of a typical window jamb detail, Turrell bevels the edge of the square aperture until it is razor-thin, which projects the sky to a horizontal picture plane within the room. The minimal edge of the frame manipulates spatial references and frames views strangely, disrupting the perception of distance by bringing together divergent points near and far. Enacted through architectural details, this window becomes an opaque surface to look at and around, rather than a threshold to look through.

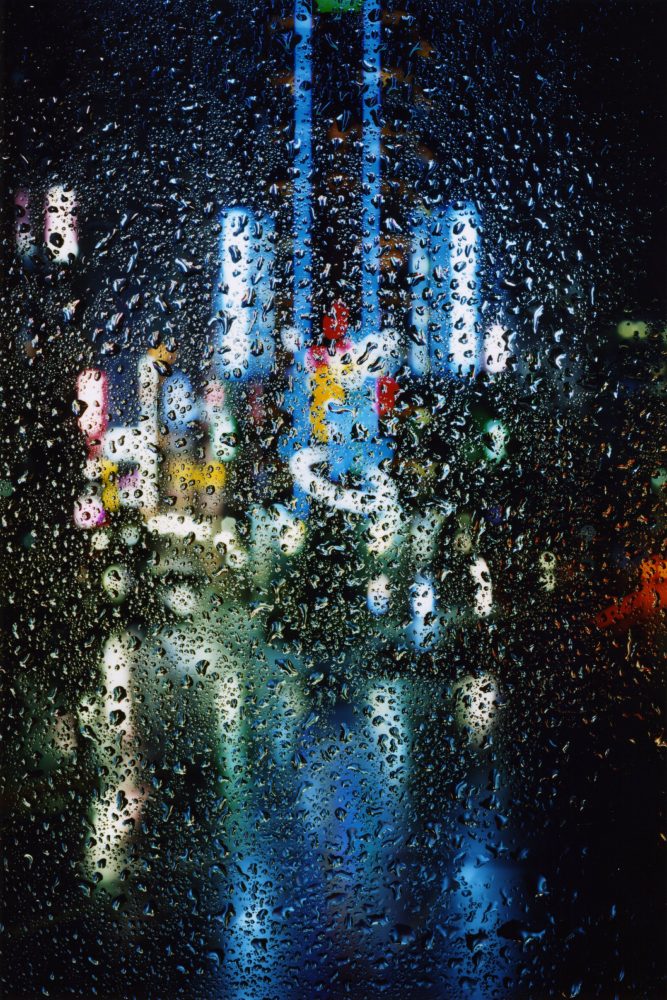

When a window’s frame is thin and forms the figure of a void, the territory beyond appears as a depthless image and the window transforms into an analog screen. The sensibilities of this hybrid window typology are also enacted in Robert Irwin’s installation 1°2°3°4° (1997) at the MCA San Diego. He punctures three rectangles from the gallery’s existing tinted ribbon window and removes the translucent glazing to allow for unobstructed, unfiltered views of the Pacific coast. When condensation collects on the glass, the opacity increases and emphasizes the deleted panel. The act of subtraction positions frames within frames, and Irwin’s newly cut windows seem to animate distant views on the surface of a computer screen. They transmit moving images into the room, inviting visitors to notice what is on display inside and outside the frames rather than the windows themselves.

-

Robert Irwin, 1°2°3°4°, 1997

Apertures: Left, 24 x 30 in (61 x 76.2 cm); Center, 24 x 26 in (61 x 66 cm); Right, 24 x 30 in (61 x 76.2 cm)

Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, Becky Cohen

© 2022 Robert Irwin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

These windows are disinterested in achieving pure transparency, preferring to mediate vision by tampering with the frame. Tethered to two places at once, inhabitants are asked to occupy both the space of imperceptible depth and the room itself. When a collection of rooms overlooks one another through several analog screens, the affect heightens. Kazuyo Sejima & Associates’ House in a Plum Grove (2003) in Tokyo reduces the legibility of the frame by cutting windows from paper-thin, steel plates that taper to 16 millimeters inside. Nearly invisible window frames flatten adjacent rooms, bodies and activities, and as one looks through layers of perforated walls, domestic life unfolds as a series of graphic images. If Le Corbusier choreographed views of the landscape through the horizontal strip of the fenêtre en longueur, Sejima frames glimpses of rooms through square windows, like Polaroid snapshots. Each room becomes a screen, and the house, a network of flickering windows.

-

Luisa Lambri. Untitled (House in a Plum Grove, #01), 2004

Laserchrome print

70.4 x 84 cm

Courtesy Gallery Koyanagi, Tokyo; Thomas Dane Gallery, London

© Luisa Lambri

A photograph of the dining room in House in a Plum Grove bears an uncanny resemblance to Tracer (1963), one of Rauschenberg’s silk-screen paintings that collages Peter Paul Rubens’s Venus in Front of the Mirror (1615). In both the photograph and painting, we inhabit the picture and our eyes focus on the corner of a white room interrupted by a large window or mirror. Rauschenberg’s Venus is depicted through double vision, her face revealed in reflection and her belly button superimposed on her back. Positioned simultaneously in two directions, her ambiguous posture indicates she is looking at a glossy surface and back at the room. Similar to Sejima’s window, the mirror transforms into a screen and Venus looks outward, only to peer into another interior dimension.

-

Hisao Suzuki, House in a Plum Grove by Kazuyo Sejima & Associates, 2003

© Hisao Suzuki

Upon closer look, Rauschenberg partially paints over the outline of Venus’ mirror, rendered as a beveled edge that subtly shimmers from Rubens’ chiaroscuro. Rauschenberg obscures this seam, erasing the distinction between foreground and background. As if gazing from a rear-view mirror, Venus floats amidst the noise, immersed in data copied from external sources, and asks us: what remains once the frame disappears and the familiar separation between viewer and subject become intimately close?

-

Robert Rauschenberg, Tracer, 1963

Oil and silkscreen ink on canvas

84 1/8 x 60 in (213.7 x 152.4 cm)

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri Purchase

© Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

As our communication becomes increasingly remote and our eyes affixed to screens, our interaction with windows and their views can seem surreal when the frame is virtually missing. As technologies advance, the desire for larger screens has pushed designers and engineers to reduce the bezel separating the screen from the outer shell of a device. The icon for Windows 11, not to mention the name of the operating system, now completely removes the mullions, frame, and any trace of perspectival distortion present in earlier logos. The iconic windowpanes evoke an “irreducible flatness,” while an invisible lattice organizes them as pixels on a screen. The glass panes levitate in space, as if held together by thin air. Without a larger window frame, what substance binds them together?

-

Microsoft, Windows 11, 2021

© Microsoft

“How the world is framed may be as important as what is contained within that frame,” writes Anne Friedberg. While the content of what we see constantly shifts, the critical question is the frame itself. Simply recreating rather than translating technological screens offers no release from digital screen inundation. The built environment requires an architectural response that not only logistically supports electronic infrastructure and digital usage, but also materially embodies how screens have fundamentally redefined the way we see and the way we live. Analog screens offer insight into how we can integrate the way we interpret information through screens into the built environment, where the potential to quietly reactivate spaces lies in the design of windows. They provide an outlet or portal to glimpse an alternative, as built artifacts in an increasingly immaterial world that respond to these currents around us.

TOP: Robert Irwin, 1°2°3°4°, 1997

Apertures: Left, 24 x 30 in (61 x 76.2 cm); Center, 24 x 26 in (61 x 66 cm); Right, 24 x 30 in (61 x 76.2 cm)

Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, Becky Cohen

© 2022 Robert Irwin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Abigail Chang

Abigail Chang is a designer and educator from Los Angeles. Her practice is interested in subtle encounters that are driven by material qualities and details, responding to currents in contemporary culture. Her work has been exhibited internationally, including the 2019 Lisbon Architecture Triennale and the 2021 Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism, and as a solo exhibition, “Reflections of a Room,” at Volume Gallery in 2022. Her research and writing investigates the role windows and screens have as framing devices and architectural apparatuses in the built environment. Her work is supported by the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts and the UIC College of Architecture, Design and the Arts, where she is a visiting assistant professor. Prior to starting her practice, she worked in Los Angeles, New York, Chicago, Basel, and Tokyo at firms including Norman Kelley, SO–IL, and Herzog & de Meuron. She has a Bachelor of Arts in Architectural Studies from UCLA with distinction, and a Masters in Architecture from Harvard GSD, where she was awarded the Takenaka Fellowship.