Screen Time

25 Jan 2023

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Art

- Columns

Screens are everywhere: stadiums, stations, billboards, buildings, refrigerators, thermostats, on our wrists, and in our hands. As a physical interface and virtual portal, screens are also the digital eyes that continuously monitor our front doors, pets, and babies. “Screen time” suggests we spend too much time with computers, televisions, smartphones, and tablets. Despite apps designed to monitor or control “screen time,” our reliance on screens for work, school, or pleasure makes it increasingly difficult to differentiate when “screen time” is on or off.

Today, disengagement from our surroundings and an accelerated pace of daily life is driven by the constantly scrolling, digital landscape that distracts yet binds us together. Expanding across art, architecture, and photography, several works, however, re-imagine and accentuate the time in “screen time.” Parallel currents in the production, medium and documentation of architecture reveal a nuanced approach that instead instills slowness, which has the potential to change the course of “screen time.” From image to object to building, the representation and construction of windows as screens can promote awareness in our interaction with them, positioning the passage of “screen time” instead as a poetic, temporal, and spatial layering.

As our homes transformed into multiscreen landscapes, the screen became an agent of paralyzing order and disruption. A mounting concern for excessive screen usage formalized in 1991, when the phrase “screen time” semantically shifted from defining a film’s duration to addressing our daily television consumption. With the rise of the motion picture industry in the early twentieth century, “screen time” was first used in film advertisements. This unit of measurement indicated the length of a film, previously announced in reels, or the amount of time an actor appeared onscreen. “Screen time” was impersonal, an objective descriptor that quantified the film’s content for promotion and distribution. By the early 1990s, “screen time” portrayed screens as injurious to human health, interaction, and mindfulness, something recounted in magazines, denounced by parents, and documented by photographers like Paul Graham. This new portrait captured how viewers, bewitched by “screen time,” remain strikingly still, their gaze lit by a soft glow as an endless stream of content captures, but does not release, their attention.

-

Paul Graham, Ryo, Tokyo from Television Portraits, 1994

Courtesy of Pace Gallery, Carlier Gebauer, Berlin and Anthony Reynolds, London

© Paul Graham

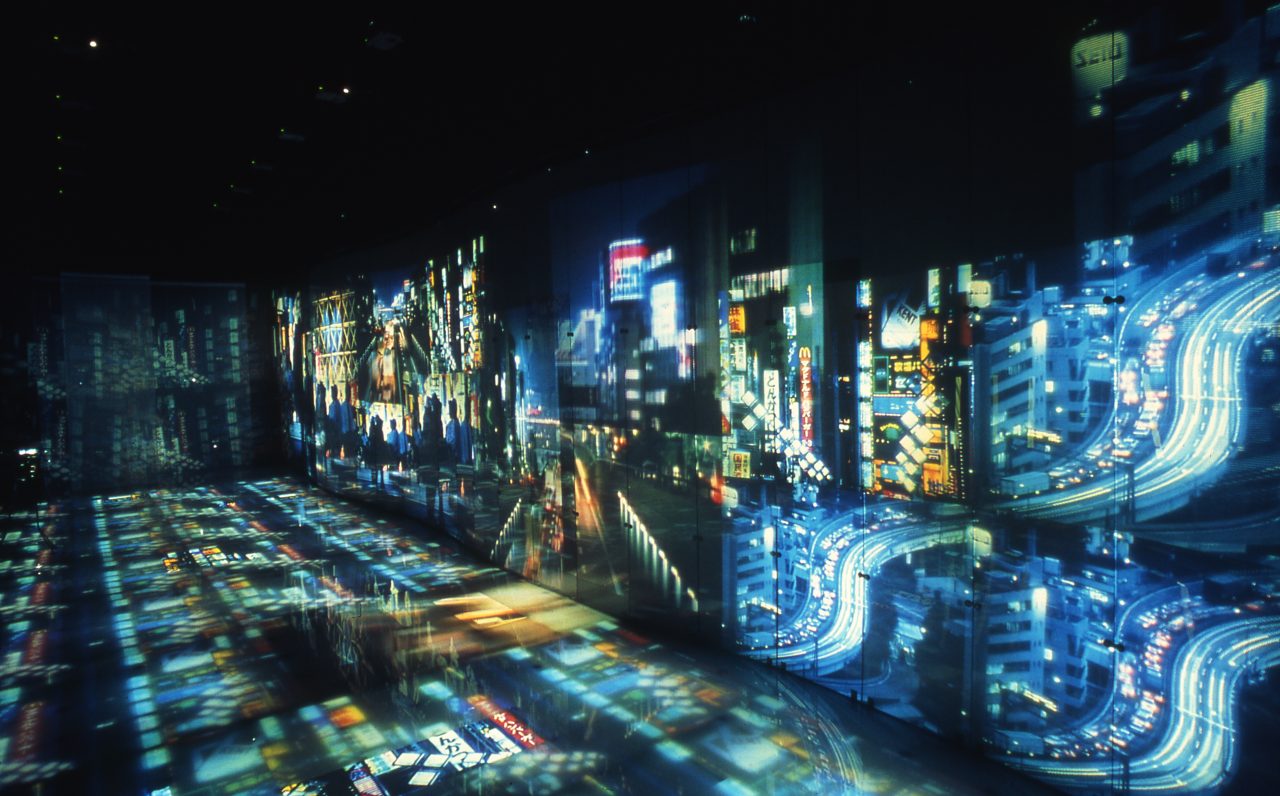

At this pivotal moment, the crisis of “screen time” was met with an architectural effervescence, where bold experimentation and confidence in the screen’s boundless capabilities were taken in stride. Rather than reflecting the cultural anxieties around screen domination or retracting into an analog world, architects immediately explored applications of screen technology. Simultaneous with the redefinition of “screen time,” Toyo Ito’s “Dreams” installation for Visions of Japan (1991) grafted scenes of the Kabukicho district onto screens at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Processed imagery devoured the gallery’s floor and walls, disembodying urban experiences into digested bytes. Meanwhile, the InterCommunication Center created a virtual exhibition, a Museum Inside the Telephone Network (1991), by organizing channels of audiovisual works, accessible only from personal devices at home and around Tokyo. Today, these are no longer visions, but realities.

-

Naoya Hatakeyama, Dreams by Toyo Ito & Associates from Visions of Japan, 1991

© Naoya Hatakeyama

But in fact, the notion of “screen time” to indicate digital usage is already outdated. We do not have the option to plug in and unplug at will. Giuliana Bruno, in her book Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality and Media, writes, “The screen has become an ever-present material condition of viewing,” a continuum that cannot be broken. Digital screen immersion affects the way we look at the world, and how we sense the built environment has been intimately, irreversibly changed.

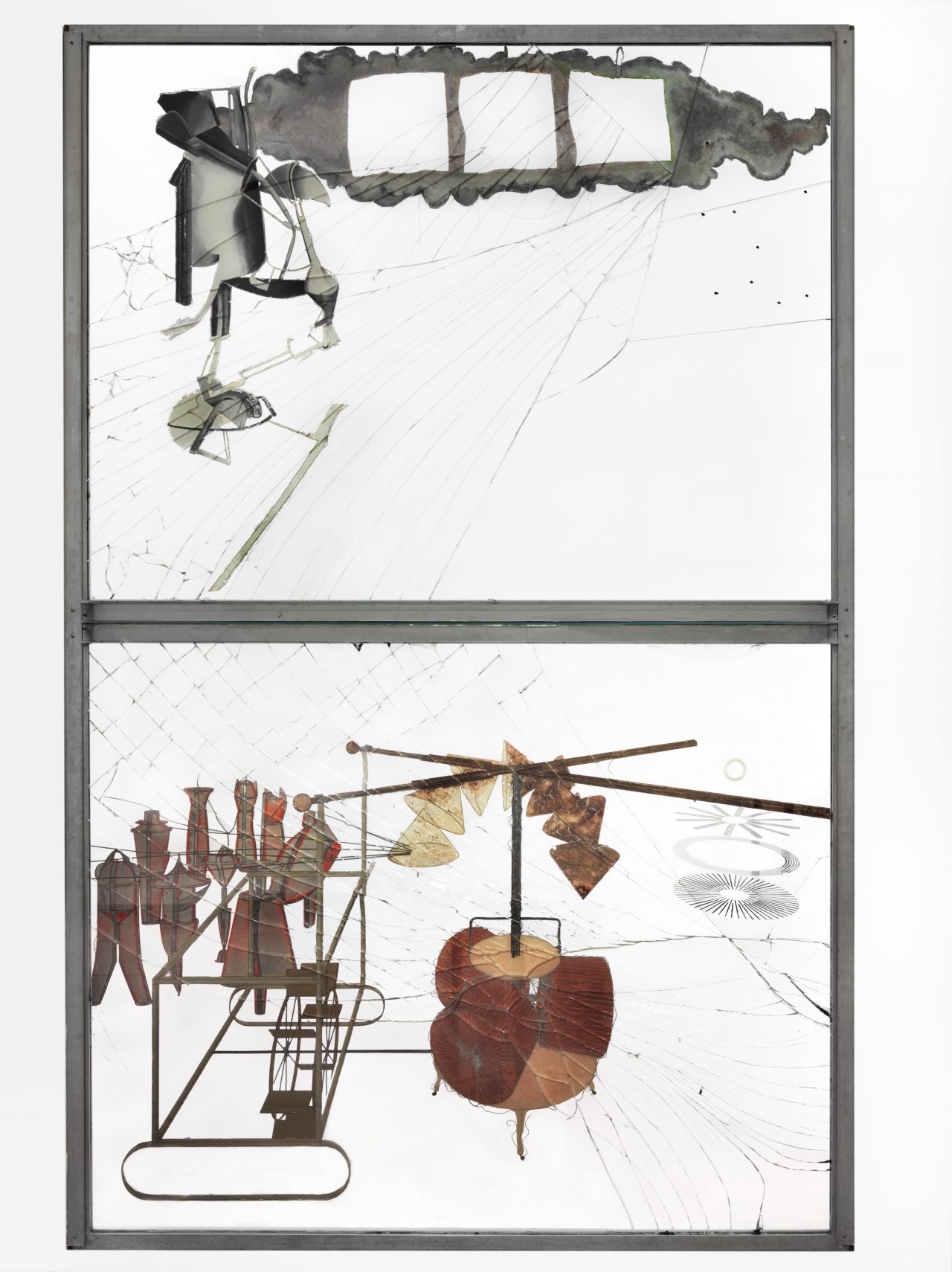

Before the proliferation of screen technology, the emergence of the screen as “an ever-present material condition of viewing” was underway, foreshadowed in projects that grappled with new methods of interpreting information and in works that introduced unfamiliar ways of seeing through immaterial networks. Perceived as a window, Marcel Duchamp’s freestanding work The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even or The Large Glass (1923) interrupts a transparent sheet with opaque objects. An ensemble of flattened, multimedia characters levitate between two large glass panes held together by a metal frame, producing a referential screen. These objects distill and recreate figures from Duchamp’s oeuvre without their original background, displaying them against a changing environment like a green screen, where viewers must map out a web of data and decipher an evolving, self-generating context that fills the void. Duchamp’s viewing portal is an unmistakable prototype that anticipates our contemporary visuality of seeing through screens.

-

Marcel Duchamp, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915-1923

Philadelphia Museum of Art: Bequest of Katherine S. Dreier, 1952, 1952-98-1

© Association Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2022

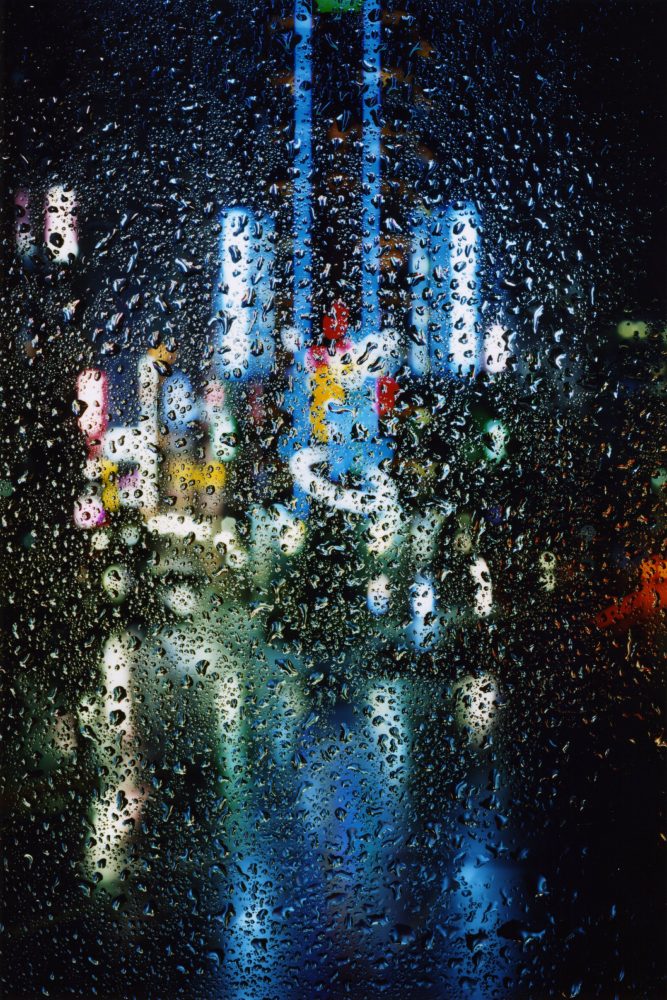

In his Slow Glass series, Naoya Hatakeyama photographs scenes of urbanity at twilight. A sheet of glass, clouded with water droplets, is positioned in the foreground and in focus. Behind the transparent pane, Hatakeyama captures street lamps, signage, and artificial lights from buildings through long exposure, producing an illegible picture where streams of neon lights trace past and present. These photographs, which contemplate the view from a window, ruminate on novelist Bob Shaw’s stories that detail the fictitious, optical properties of “slow glass,” which records and mirrors a distant memory.

While “slow glass” remains in the world of science fiction, architects have mused on its adaptation to buildings. The ability to see a past event is interpreted through technology in Diller + Scofidio’s aptly named Slow House (1991), where a large screen is installed in the place of a picture window. The architects give inhabitants agency to remotely control their view by projecting images of the Atlantic Ocean, which the house faces, in real time or in playback. Slow Glass and Slow House ask the window to mediate as a viewing apparatus and to render an ambiguous perception of time.

-

Naoya Hatakeyama, Slow Glass / Tokyo #112, 2009

© Naoya Hatakeyama

The narrative of screens in architecture, however, should focus less on what the screen displays, and rather on how and why it affects the surrounding environment. For Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Theaters, a reduced pace is essential for the legibility of an architectural interior. In a single frame, he captures a projection screen in a dark, empty theater through long exposure and the film footage dissolves into a white blur. The screen’s brilliance is an emptiness that beams with latent energy, materializing the vaulted ceiling, wooden stage, and plush curtains. These photographs invite us to consider the space around the screen, the room, and the body, and to reflect on how “screen time” no longer suggests passive reception but active participation.

-

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Goshen, Indiana, 1980

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of Gallery Koyanagi

© Hiroshi Sugimoto

Luisa Lambri portrays Sugimoto’s screens in her serial photography of windows. Often concealed by blinds, shutters, or condensation, she re-presents windows that are at once familiar and unidentifiable. From an oblique view, the window becomes a luminous screen that cannot be seen through, but rather radiates light and hides what lies beyond. Subtleties in shadow and reflection are quietly perceived over hundreds of stills, as palpable fragments from a dream. Her apertures emit a hazy gleam, an ethereal quality that allows viewers to float between the screens. The techniques of long exposure and seriality presented in the photography of Hatakeyama, Sugimoto and Lambri challenge the notion of “screen time,” not as something that should be limited but savored.

-

Luisa Lambri, Untitled (House in a Plum Grove, #02), 2004

Laserchrome print

102 cm x 84,9 cm

Courtesy Gallery Koyanagi, Tokyo; Thomas Dane Gallery, London

© Luisa Lambri

Beyond the camera lens, buildings can also produce an architectural language that translates digital screens, expanding from a single interface to a complete spatial experience absorbed over time. Unhampered by conventions in a new digital territory, some architects instead call us to relish “screen time” through informational media immersion.

In Pachinko Parlor II (1993), Kazuyo Sejima & Associates attaches a slender, transparent entry hall to an existing arcade in Ibaraki, Japan. Across the building’s glass envelope, “KINBASHA,” the name of the gaming company, is repeatedly painted in full bleed, horizontal strips of text. Some letters are partially deleted and register as fragments of a scrolling message display board. This graphic detail gives viewers the perception of long exposure, where the words lift off the surface of the glass and meander across the interior floor and opposing wall as shadows. To enter the arcade is to slip into the seam between the glass and componentry of digital screens, lingering in the aperture as the shutter slowly closes.

-

Nacasa & Partners Inc., Pachinko Parlor II by Kazuyo Sejima & Associates, 1993

© Nacasa & Partners Inc.

Nearby, Pachinko Parlor I (1993) positions a single black panel on the storefront, interrupting the glass façade like a dead pixel on a computer screen, recalling a similar composition to Duchamp’s. Inside, “KINBASHA” is boldly printed in different sizes. Clear and rippled mirrors wrap around walls, stairs, walkways, and ceilings to reflect the text in deceptive orientations. At night, the arcade’s interior is a backlight that projects reflections of itself onto the facade as ephemera, where text and imagery flash and echo. The play of surfaces diffract and distort the building’s interior views as if capturing serial images from one vantage point. Harnessing these qualities, the building narrative does not aim for clarity or transparency, instead asking visitors to patiently observe subtleties in the environment. Untethered to a single aperture or glass pane, the Pachinko Parlors’ precise material details embody long exposure and seriality to encourage slowness, where architecture as media unfolds gradually.

-

Shinkenchiku-sha, Pachinko Parlor I by Kazuyo Sejima & Associates, 1993

© Shinkenchiku-sha

What is the role of architecture if not to interpret the screen’s sensibilities in a building language, to respond to contemporary conditions rather than be overwhelmed by them? Re-reading “screen time” through the lens of architecture, to study the screen not as a piece of technology but as a membrane that physically surrounds us, more accurately reflects our cultural moment.

Today, “screen time” is no longer a social critique but a pervasive condition. The screen has long been inseparable from the everyday and our attitude toward “screen time” continues to resonate with our ever-evolving relationship to screens. In a collection of notes made while developing The Large Glass, ephemera enclosed in The Green Box (1934) includes an inscription about “delay in glass.” Neither picture nor painting, Duchamp calls the work a “delay in glass,” a condition that postpones becoming either. Borrowing from Duchamp, “screen time” today is a delay that merely reflects how we receive and distribute information, how we sense and make sense of our built environments. It is a blurring that offers multiple perspectives layered on top of one another and placed in relation to one another, encountered as a dense web that reaches deeper than the surface.

Top: Paul Graham, Ryo, Tokyo from Television Portraits, 1994

Courtesy of Pace Gallery, Carlier Gebauer, Berlin and Anthony Reynolds, London

© Paul Graham

Abigail Chang

Abigail Chang is a designer and educator from Los Angeles. Her practice is interested in subtle encounters that are driven by material qualities and details, responding to currents in contemporary culture. Her work has been exhibited internationally, including the 2019 Lisbon Architecture Triennale and the 2021 Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism, and as a solo exhibition, “Reflections of a Room,” at Volume Gallery in 2022. Her research and writing investigates the role windows and screens have as framing devices and architectural apparatuses in the built environment. Her work is supported by the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts and the UIC College of Architecture, Design and the Arts, where she is a visiting assistant professor. Prior to starting her practice, she worked in Los Angeles, New York, Chicago, Basel, and Tokyo at firms including Norman Kelley, SO–IL, and Herzog & de Meuron. She has a Bachelor of Arts in Architectural Studies from UCLA with distinction, and a Masters in Architecture from Harvard GSD, where she was awarded the Takenaka Fellowship.