Georgia O’Keeffe and Her Windows in New Mexico

24 Jun 2022

At age 62, after living between New York City and New Mexico for many years, artist Georgia O’Keeffe made rural Northern New Mexico her permanent home. There, she lived between two adobe homes well into her nineties. She improved these houses in a variety of ways and made changes to their windows particularly often. We trace her footsteps by way of the changes in her homes over the decades through this interview with Dr. Sarah Rovang, architectural historian and former Research Fellow at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Please tell me about how you came to become a Research Fellow at the Museum.

A few years back, the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum was in the process of creating a conservation management plan for O’Keeffe’s house in Abiquiu. The conservation team included historic architects, adobe conservators, historic site managers, and structural, environmental, and geotechnical engineers—but they needed an architectural historian to answer some of the questions they had regarding specific details in the house, and to situate those details within a broader historical and cultural context. They invited me in to do archival research and provide insight about three areas: the home’s architectural finishes, the fallout shelter that O’Keeffe had constructed in the early 1960s, and the windows, with a particular emphasis on the large picture window in her sitting room.

I have always been interested in the collision of industrial and traditional building techniques in the early and mid-twentieth century. O’Keeffe’s homes, particularly the house at Abiquiu, are amazing examples of how mass-produced materials and vernacular architecture can coexist within a single building. The juxtaposition of steel and glass and traditional adobe in both of O’Keeffe’s homes is formally compelling but poses some thorny interpretive questions for an architectural historian (as well as some tricky conservation issues for a preservationist!).

-

Photograph by Ryan Lowry -

Photograph by Ryan Lowry

I’d like to start by asking about the circumstances that led O’Keeffe to build a home in New Mexico. While she originally worked out of New York, she purchased land and a home at the age of 46 in Ghost Ranch in Santa Fe. What do you think led her to decide to move to New Mexico?

There were many factors at play that led to the artist moving to New Mexico, but O’Keeffe was one of the rare artists who was able throughout her career to inhabit “insider” and “outsider” statuses simultaneously. Especially as she was establishing her career and building her reputation, she recognized the value of being part of the New York art world, and all the connections, opportunities, and exposure afforded by that life. At the same time, she had a strong streak of individualism and an affinity for the landscapes of the American Southwest. The scale, colors, geometries, and built environment of New Mexico were closely aligned with many of the formal questions and approaches to abstraction that she was exploring in her work.

Yet a few years later, O’Keeffe acquired a second home built on land she purchased in Abiquiu, about 20 kilometers away.

The house at Ghost Ranch (built 1933) is on an exposed piece of land near the mouth of a box canyon. The scenery is breathtaking—and was a major source of inspiration for O’Keeffe’s painting—but it gets very cold there in the winter and the soil is extremely arid. In part because it was so challenging to get certain commodities and food to Ghost Ranch, O’Keeffe very much wanted to have a garden. The Abiquiu property came with water rights, which is a big deal when you live in New Mexico. Even though Abiquiu is only 20 km away, the climate is much more temperate and was a better winter home for O’Keeffe.

-

Photograph by Ryan Lowry

It seems that the home in Abiquiu was in ruins when she first bought it.

Its roofs had mostly caved in, and there was even one room that was serving as a makeshift goat pen. I love O’Keeffe’s description of first exploring the ruin:

“When I first saw the Abiquiu house it was a ruin with an adobe wall around the garden broken in a couple of places by falling trees. As I climbed and walked about in the ruin I found a patio with a very pretty well house and a bucket to draw up water. It was a good-sized patio with a long wall with a door on one side. That wall with a door in it was something I had to have. It took me ten years to get it—three more years to fix the house so I could live in it—and after that the wall with a door was painted many times.”

-

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), Black Patio Door, 1955, Oil on canvas, 40 1/8 x 30 in. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas. 1966.19 © Amon Carter Museum of American Art

How did she start repairing the home?

Not long after O’Keeffe finally acquired the house at Abiquiu at the end of 1945, her husband and artistic collaborator, Alfred Stieglitz, passed away in New York. She spent much of the next three years in New York City settling his estate. While she was busy in New York, she asked her friend Maria Chabot to oversee the reconstruction of the Abiquiu house. Chabot, who spoke fluent Spanish, basically functioned as a general contractor, hiring local labor and managing materials purchases.

In 1949, O’Keeffe finally moved in. In a lot of ways, Chabot was able to preempt the kinds of spaces, views, and amenities O’Keeffe wanted from the Abiquiu house. But it was only through the process of living in the house over an extended period that O’Keeffe was able to make decisions to suit her evolving needs and aesthetic sensibilities. Like the way she would rework a motif in her painting over and over again, the Abiquiu house was a constant site for architectural experimentation and reinvention.

-

Photographer: John Candelario, Left: Georgia O’Keefe; right: Maria Chabot. Georgia O’Keefe residence, Ghost Ranch, near Abiquiu, New Mexico, Courtesy of the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA), 165668

Most of all, it seems that O’Keeffe remodeled her windows time and time again. Why was that?

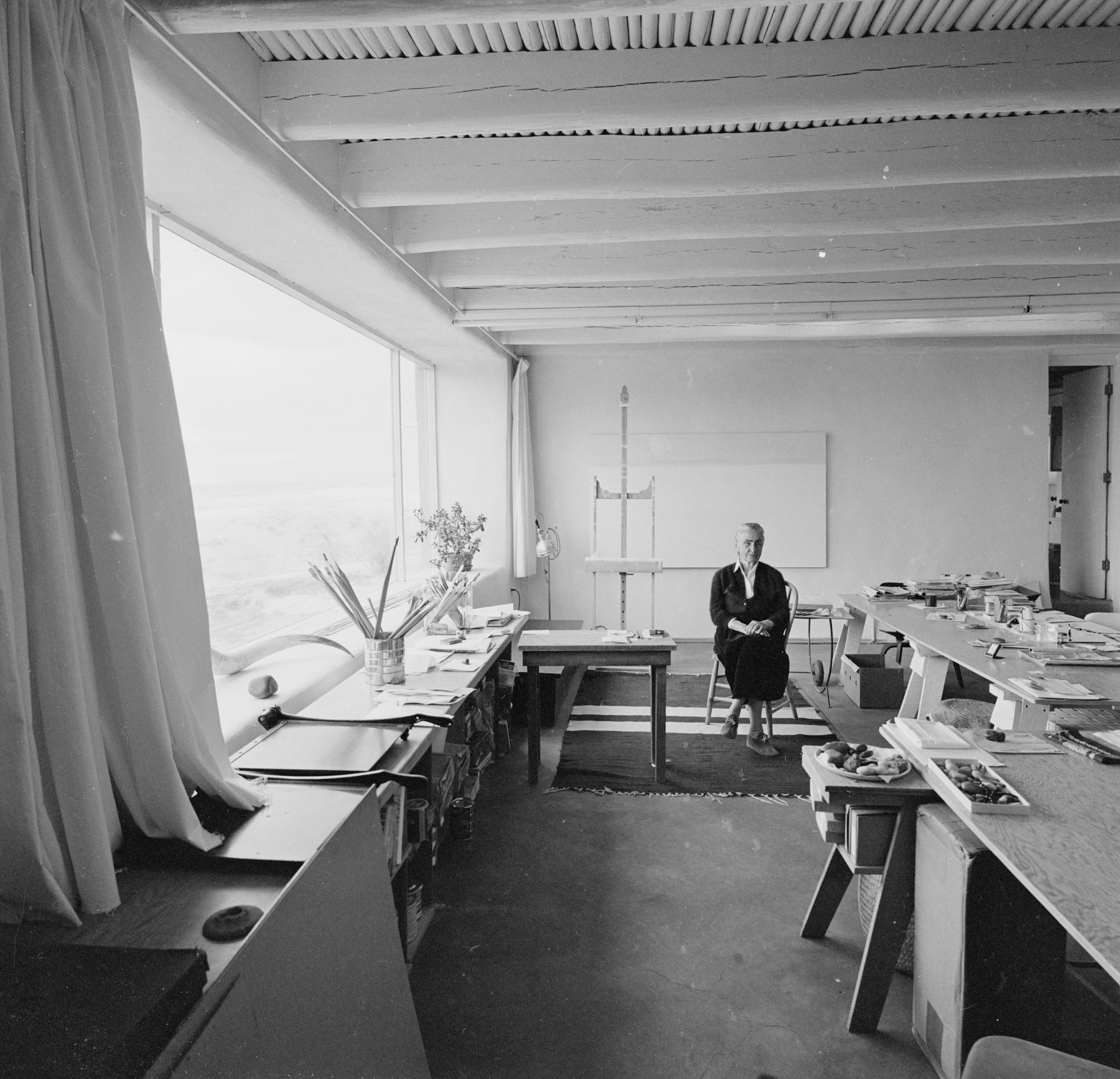

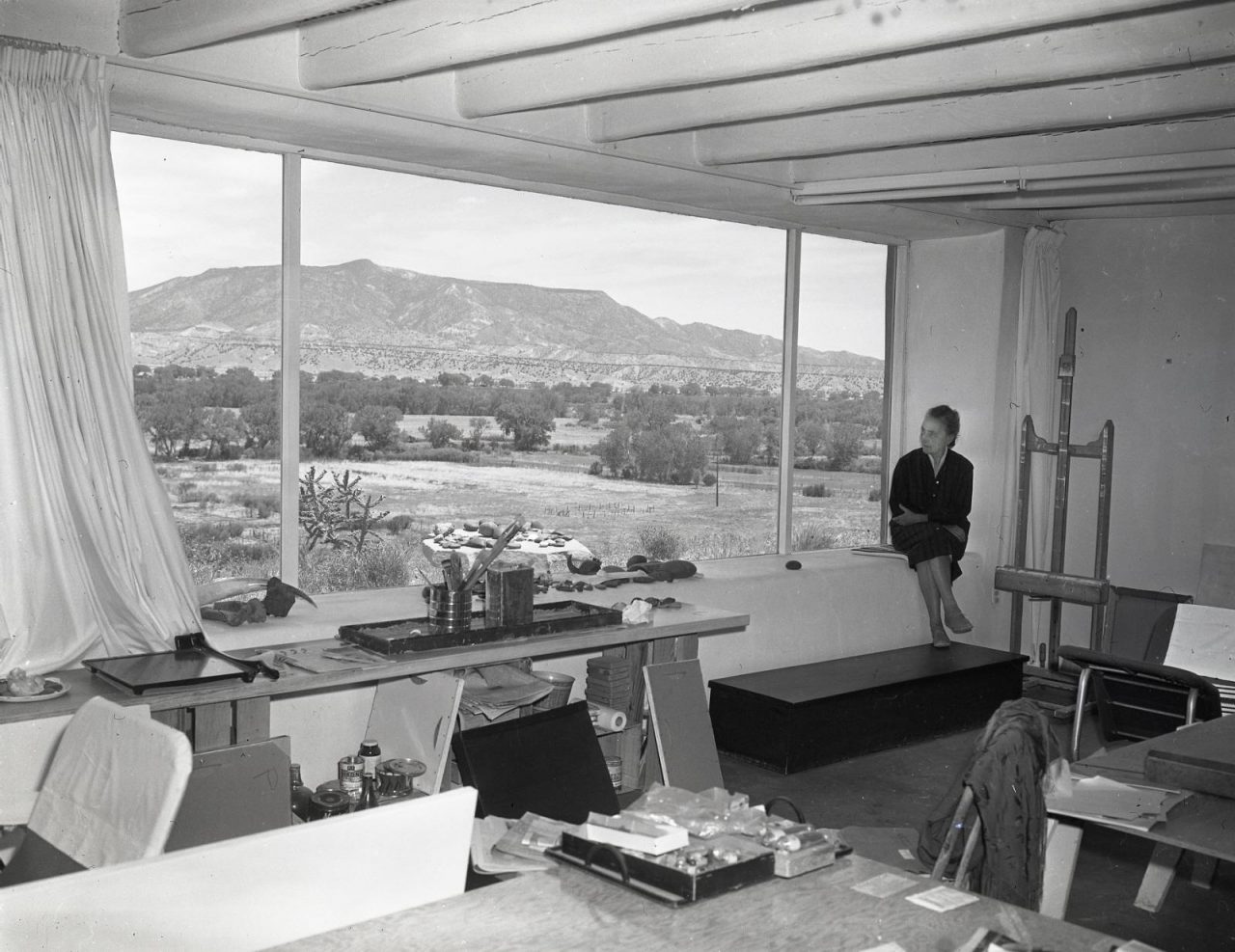

O’Keeffe’s creative practice was all about framing views. Given her relationship with Alfred Stieglitz and her close friendship with many other photographers, it isn’t surprising that previous scholars have pointed to the importance and impact of photography on O’Keeffe’s work. But I think that the concept of architectural framing is just as important for understanding O’Keeffe, and that’s where her fascination with windows comes in.

In 1953, she told her friend Frances O’Brien, “You’d be amused though, at how many people never noticed the view until it was framed by my studio window.”

I found it quite significant that just as O’Keeffe liked to repeat motifs in her painted work, she also repeated architectural motifs between her two houses—especially in the changes made to the windows. For instance, in both homes, she incorporated a wraparound corner window—at Abiquiu in her bedroom and at Ghost Ranch in a breakfast nook that she added sometime the 1960s.

O’Keeffe was certainly aware of modernist architectural idioms but I don’t think her window renovations were ever executed with the intention to “be more modern.” Instead, they were about capturing a particular landscape, the “faraway nearby,” as she said. As O’Keeffe put it, “I did many things over. I didn’t want it to be Indian. I didn’t want it to be modern. I just wanted it to be my house.”

-

Georgia O’Keeffe sitting down for supper, Ghost Ranch dining room. In the background is the potting shed, March 1975. Photograph by Dan Budnik. ©2022 The Estate of Dan Budnik. All Rights Reserved.

-

View Looking East from O’Keeffe’s Abiquiu Bedroom. Photograph by Ryan Lowry

Do you think these various improvements to her living space also had an influence on how she created her work?

I think the renovations impacted O’Keeffe’s work and that O’Keeffe’s painting reciprocally influenced the innovations! I don’t think that it is a coincidence that O’Keeffe knocked out a wall and installed a massive picture window in her sitting room in 1964, around the same time that she was painting very large, abstract landscapes, often inspired by her international travels and view from an airplane.

On the other hand, you also once wrote in an article that “O’Keeffe frequently talked about ‘thinking on a wall’ and the necessity of blank, neutral wall space for her process of visualizing a composition.”

Among modern painters, O’Keeffe was particularly attuned to the impact of her work within architectural spaces. In the early part of her career, O’Keeffe unfailingly hung her own shows. That experience ensured in the coming decades, she painted knowing that her work would be up on a wall, whether in one of her homes, the Museum of Modern Art, or the home of a collector. There are accounts of her hanging art at both Ghost Ranch and Abiquiu to “test it out” on visitors and housemates.

-

Georgia O’Keeffe standing at cloud painting, Albuquerque Museum, gift of the Estate of Ralph and Clarabel Looney, PA2006.021.055

You mentioned picture windows, and one of the most impressive is certainly the 4.8m x 3m studio window. With a window as large as this, were there any issues with room temperature, humidity, or ventilation given the weather and climate in Northern New Mexico?

Great question! Given all those factors, it is staggering that this massive window has remained as stable as it has over the years. Maria Chabot was able to work her local connections and somehow managed to get a massive steel beam to support the window even though there were severe material shortages in New Mexico after World War II.

Because of the heaviness of adobe, windows in adobe structures were traditionally very small. They might be framed with wood (often with a single beam above the window) and let in just a little light. O’Keeffe’s desire for large picture windows in keeping with a modernist aesthetic must have been a challenge for the local builders who installed them. Adobe (when properly constructed) mitigates temperature and humidity change quite efficiently. But heating was certainly a concern for the studio! Even though Abiquiu is warmer than Ghost Ranch, the Abiquiu house is still up on an exposed cliffside. In Chabot’s original plans, she had worked out a very sophisticated radiant heating system for the floor. Ultimately, they ended up using in-room gas heaters. It must have gotten cold in the studio, however, because O’Keeffe added a fireplace on the left side of the window in the 1970s.

-

Georgia O’Keeffe at window, Albuquerque Museum, gift of the Estate of Ralph and Clarabel Looney, PA2006.021.055

Given that O’Keeffe died over 30 years ago, was it difficult to do research on her homes and the history of how they were renovated?

O’Keeffe was a meticulous recordkeeper when it came to her art; she was very aware of the legacy that she was leaving and that her life and work would be the subject of art historical research in the future. Her correspondence has been methodically catalogued and stored at the Beinecke Library at Yale University and many of her other papers, books, and documents are housed at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum’s Research Center.

In so many ways, O’Keeffe was a very organized person, but she was also human—she occasionally used receipts as bookmarks or wrote notes to herself in the margins of books. The archivists who have worked through her documents and library following her death in 1986 have done an admirable job of cataloguing and preserving that humanity in O’Keeffe’s files.

But the archival documents related to the house are often folded into other collections and no matter how well you understand the file structure, there is still a fair amount of happenstance involved in finding what you’re looking for. It was sheer luck that led me to the receipt that finally allowed me to date the renovation of the sitting room window.

How were homes and yards like these maintained? Both are quite large, so it seems upkeep would involve a lot of work.

O’Keeffe’s life at Abiquiu was heavily dependent on the support and labor of the community. Throughout her life, she employed housekeepers, gardeners, adoberos (traditional adobe builders), carpenters, and more to help maintain her house and keep it running. Adobe is extremely good at regulating heat and humidity; it keeps you cool during the day and warm during the night. However, the maintenance is quite labor-intensive and requires a lot of traditional skill and practice. To keep the bricks from cracking and degrading over time, the exterior of the building must be replastered with mud every one to two years. There were some areas where O’Keeffe decided that the maintenance was impinging on her creative practice.

For instance, in 1959, O’Keeffe decided that she no longer wanted to have her house replastered with adobe mud, a process that was necessary at least once a year and took an entire crew of local workers. Instead, she had the exterior covered in brown concrete stucco even though she hated how it looked compared to the original adobe. O’Keeffe’s decision to switch to cement stucco rather than mud plaster in the late 1950s saved on maintenance costs and trouble for her but has posed some preservation issues. Stucco does not breathe like traditional adobe, and moisture can accrue inside the walls, leading to structural issues.

But on the inside, she kept many of the traditional adobe floors despite their fragility. Some of the adobe floors are still intact and are regularly refinished by the children of the original workers who maintained the house and grounds while O’Keeffe was living there.

-

Abiquiu Door and Zaguan, 2010. © 2010 Hester + Hardaway, Photographers -

Abiquiu House, O’Keeffe’s Bedroom Fireplace, 2010. © 2010 Hester + Hardaway, Photographers

I happened to read in a book that O’Keeffe used bed sheets as curtains at her Santa Fe home. Is that true?

That is true! Using bed sheets as curtains is something that O’Keeffe did throughout her life, even when she definitely had enough money to buy real curtains. She also used bed sheets as slip covers for her furniture for most of her life (there is still a couch in her kitchen at Abiquiu that is covered in a white bed sheet). Using bed sheets was a way for her to visually simplify her surroundings and exert control over her environment; it was part of her whole modernist aesthetic.

-

Georgia O’Keeffe opening curtains, New Mexico, 1960. Photograph by Tony Vaccaro

You also write that O’Keeffe’s homes were regularly covered by the media beginning in 1960, and that she was considered fashionable at the time. Did she have positive feelings about this kind of reporting and reception?

O’Keeffe was extremely conscious of how she was portrayed in the media, cultivating a distinct photographic persona that included her clothes, her paintings, her homes, and even her beloved Chow Chow dogs. So she exerted a lot of control over this media coverage.

O’Keeffe had always had a keen eye for modern furniture and decoration but when she renovated and redecorated her sitting room at Abiquiu in the early 1960s, the interior landscapes were colorful and composed as O’Keeffe’s paintings, and the room almost felt designed to be photographed and shown in color. An architectural photographer Balthazar Korab later described the house as “adobe combined with hard-edge modern, chairs by Eames, Saarinen, Bertoia, Navajo rugs and her loved collection of stones, bones and roots”.

I would conjecture that this might have had something to do with the increasing popularity of color printing and photography around this time and with her friendship with Alexander Girard (Architect/Designer, 1907–1993), who employed a vibrant, folk-inflected aesthetic in his interior designs. She also very much admired his home and his design aesthetic. O’Keeffe changed the design of the room changed again in the early 1970s, returning the walls to a natural adobe tone and selecting a more muted color palette for the pillows and upholstery.

Also, O’Keeffe almost never let anyone see or photograph her while she was painting, so other spaces in the house became proxies through which she communicated ideas about her creative process.

-

Abiquiu Sitting Room. Photograph by Ryan Lowry

I had imagined O’Keeffe as an artist who lived a solitary life in the Santa Fe wilderness, but it seems that in reality, many people visited her homes and she interacted with a variety of people.

In a lot of ways O’Keeffe kept a bit of distance from the Santa Fe art scene. However, she gravitated towards people with whom she could have deep conversations on a variety of topics. She was very well read in many areas.

At the beginning of the 1960s, she hired a local builder to build a fallout shelter in 1962 or 1963, drawing on readily available government plans. It is neatly concealed in the hill under her studio, except for the ventilation pipe, which can be seen from the big picture window. While researching her fallout shelter, for instance, I discovered that she had a passion for nuclear physics and was good friends with some of the scientists at Los Alamos National Laboratory. She was very concerned about nuclear proliferation and the destructive potential of the scientific discoveries at Los Alamos.

The wife of one of the physicists O’Keeffe knew related later that the artist “had a natural curiosity and was very knowledgeable. So, they enjoyed talking about a lot. They’d get into the technical things and she always had some very sensible questions to ask. [She was] not very frivolous about any of this. It was fun.” Until I started exploring her homes, I had no idea how capacious O’Keeffe’s interests were.

-

Georgia O’Keeffe and Cheese, New Mexico, 1960. Tony Vaccaro/Archive Photos/Getty Images

It seems O’Keeffe’s homes were a kind of expression of the person she was.

Wanda Corn’s wonderful book Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern argues that there really wasn’t a clear point where O’Keeffe’s art ended and her life began—her clothes, her homes, her garden, and her art were all part of a larger practice. As O’Keeffe explained in a 1976 retrospective of her work,

“An idea that seemed to me to be of use to everyone—whether you think about it consciously or not—the idea of filling a space in a beautiful way. Where you have the windows and door in a house. How you address a letter or a stamp. What shoes you choose and how you comb your hair.”

Top: Georgia O’Keeffe House, Abiquiu, New Mexico. Interior. Studio with O’Keeffe present. Balthazar Korab Studios, Ltd. LC-DIG-ppmsca-72243

Sarah Rovang

An architectural historian based in Santa Fe, New Mexico. As a Program Officer at the Thoma Foundation, she oversees grant-making initiatives and research related to rural arts and education. Born and raised in New Mexico, she holds a Ph.D. in the history of art and architecture from Brown University. Before joining the Thoma Foundation, she taught architectural history at the University of Michigan, traveled around the world as the Society of Architectural Historians’ H. Allen Brooks Traveling Fellow, and was a Research Fellow at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe.