Series The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Windows: Openings and devices

12 Dec 2018

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Interviews

Laurent Stalder, a professor at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETHZ), has researched various threshold devices in architecture, and published about the topic under the title “Threshold Atlas”.

In the collaborative study with the Window Research Institute, Stalder researches the nature of openings in iconic works of architecture by the likes of Mario Botta and Le Corbusier, while also speaking about realizing the unexpected diversity and creativity that he found when looking at the many anonymous patents regarding windows involved in their development.

The Window Research Institute had the opportunity to interview Stalder at the Venice Biennale 2018, where he served as one of the curators of the “Architectural Ethnography” Japan Pavilion.

You have focused your research primarily on the history and theory of architecture at ETHZ, and we have collaborated on “Windowology Research” (research on windows) since 2016. Could you tell us more about this endeavor?

Surprisingly, the window does not occupy a central position in contemporary architectural theory. It is either treated in handbooks as a technical problem, or in art-historical studies as a purely formal one. Yet the everyday language of windows is richer and much more differentiated. There are bay or bow windows, sash or lattice windows, airflow or smart windows, and control or cockpit windows. And if we extend the narrow definition of the window as an element of a building, we could even include the periscope or the peephole within this category.

-

List of windows © Laurent Stalder, ETH Zurich

Therefore, it was crucial for our research to understand the window not only as a hole in the wall, but also as a device that articulates our relationship to the outside. A window not only frames a view or excludes the wind, as the etymological definition of the window as a “wind-eye” suggests, but also caters to a diversity of requirements, such as the intensity of light or the need for privacy.

Could you describe some of these diverse aspects to us?

For example, in the house designed by Swiss architect Mario Botta in Cadenazzo, a small village in Ticino, Switzerland that has been overrun by suburbanization, Botta introduced four large circular or semicircular windows in an otherwise completely closed volume. The placement of these openings frames the magnificent alpine landscape beyond the immediate suburbanized neighborhood and its monotonous architecture, thus transforming the house in a camera-like device focused on the mountain peaks on the other side of the valley.

-

Set on a hillside, the house opens onto the north towards the plain and the mountains.

The compact prism-shaped volume is clad in blocks of concrete.

The large openings in the loggias frame the views.

Mario Botta: Caccia House, Cadenazzo, 1970-1971 © Mario Botta Architetti

-

Mario Botta: Caccia House, Cadenazzo, 1970-1971 © Mario Botta Architetti

Scholars have shown, like Bruno Reichlin (architect and professor, University of Geneva) in “The Pros and Cons of the Horizontal Window. The Perret – Le Corbusier Controversy” (1984), that Le Corbusier was particularly sensitive to these issues of framing. The story goes that for the little house Le Corbusier built for his mother on the shore of Lake Geneva, the choice of the panorama to be framed preceded the location of the house. Whether this anecdote is true or not, the long window is the central element of the house, as it transforms the surrounding landscape, the lake and the alps into a long panorama. The precise framing cuts out the foreground and the background, flattening the middle-ground into a long picture when viewed from the living and dining room.

For the Petite Maison in Corseaux, Le Corbusier worked with conventional windows, whereas for the Paris apartment of eccentric multimillionaire Charles Beistegui starting in 1929, he uses several devices, including a periscope and a movable hedge. The apartment was designed on the rooftop of an existing building on the Champs Elysées. The periscope allowed for a voyeuristic view of the French capital. One could see the city without being seen. The hedge in turn staged and framed the monuments of Paris when moved.

At ETHZ, your research is focused on the history and theory of architecture, especially from the 19th to the 21st century. Why do you think it is important to research this period? Is this also the case when it comes to windows?

It seems impossible today to engage with architecture without taking into account the importance of technology as a key component of architectural culture. In this sense, the 19th century, at least in Europe, marked a rupture as the consequences of the Industrial Revolution began to transform the field of architecture at a deep level. Water, gas, and electricity were introduced into the household. Devices or machines, like warm water heating, toilets, and elevators, transformed the way in which buildings were organized. Equally, new materials like steel, and later concrete, reshaped the building trade. All these seem to be good reasons to begin a genealogy of contemporary architecture in the 19th century.

For a research project that we conducted some years ago and published under the title “Threshold-Atlas” (“Schwellenatlas”) we concentrated on various threshold devices, like door openers, revolving doors, and air curtains, which had been introduced into architecture over the past 150 years. As this timeframe proved to be very fruitful, when we were asked by the Window Research Institute to participate in their project on windows, we similarly and quite naturally decided to take the mid-19th century as the starting point for our research. Not only did new construction techniques allow for bigger openings, thus challenging the form of the traditional window, but innovations in glass technology, through the improvement of its physical and chemical constitution, also introduced new usages and applications. The 19th and 20th century brought about a tremendous transformation in the production and construction of windows, transforming them from simple glazed openings into highly specialized performative devices. Windows today filter light, collect energy, absorb heat, and much more.

Therefore we focused our research less on individual architects than on other actors, like engineers. We were less interested in iconic architecture than in understanding new forms of knowledge that emerged from the laboratories, factories or workshops of the 19th and 20th century. As such, during the first phase that we conducted, we focused on patents. Their unexpected number and diversity are proof of the enormous energy that has been expended in the development of the window. A lot of these patents, naturally, would never find an application, yet they reflect the incredible creativity and imagination of their inventors. These ideas alone seemed to us to be worth investigating. Our research allowed us to question one common hypothesis in particular: that industrialization brought about a complete normalization of the window. This might be true in the building trade, but certainly not in the imagination of the engineers.

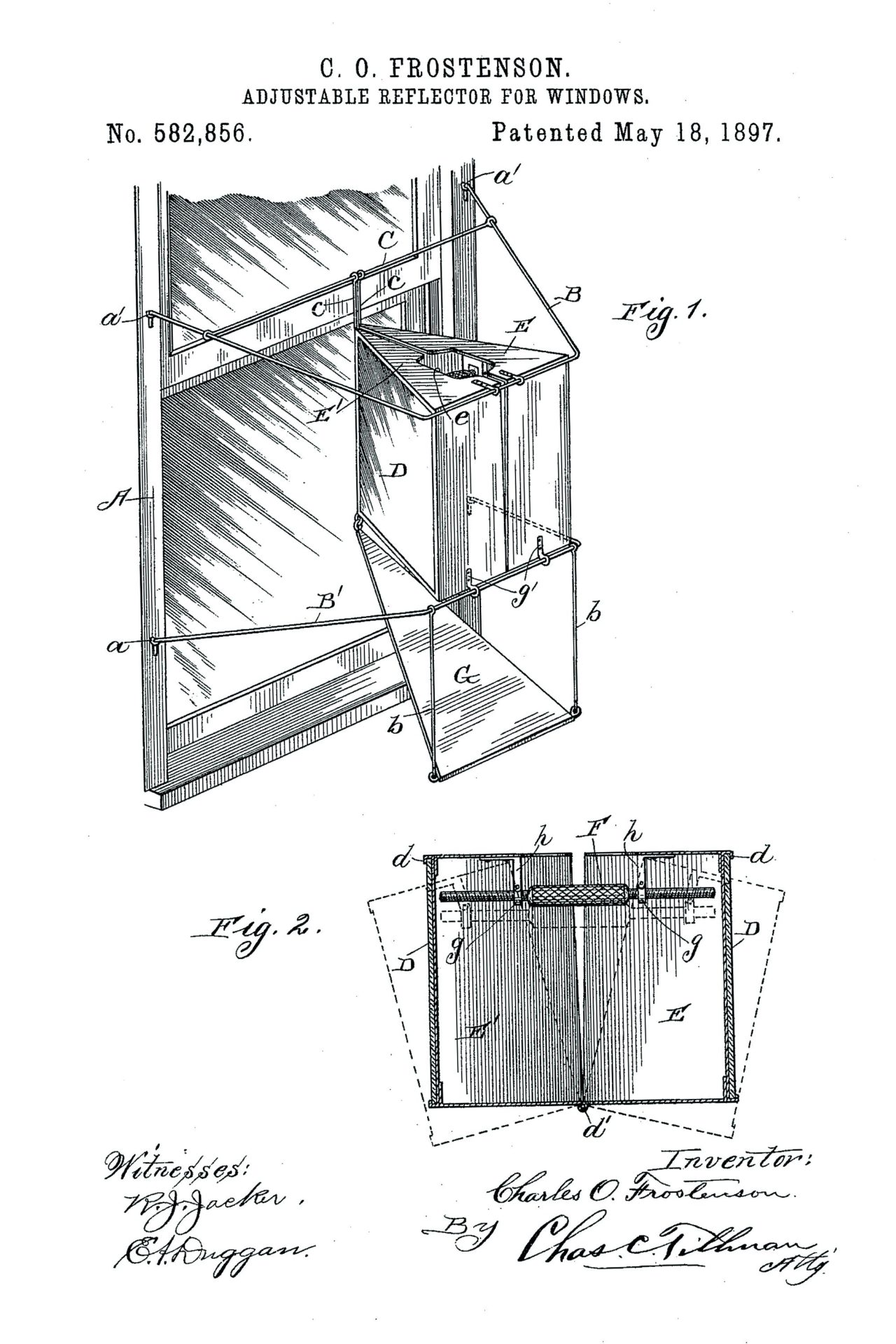

Look, for instance, at the patent for an “adjustable reflector for windows” from 1897, which could literally turn the gaze of the viewer around the corner.

-

Adjustable Reflector, 1897

The inside of the device has a mirror which allows a person inside to look down the street.

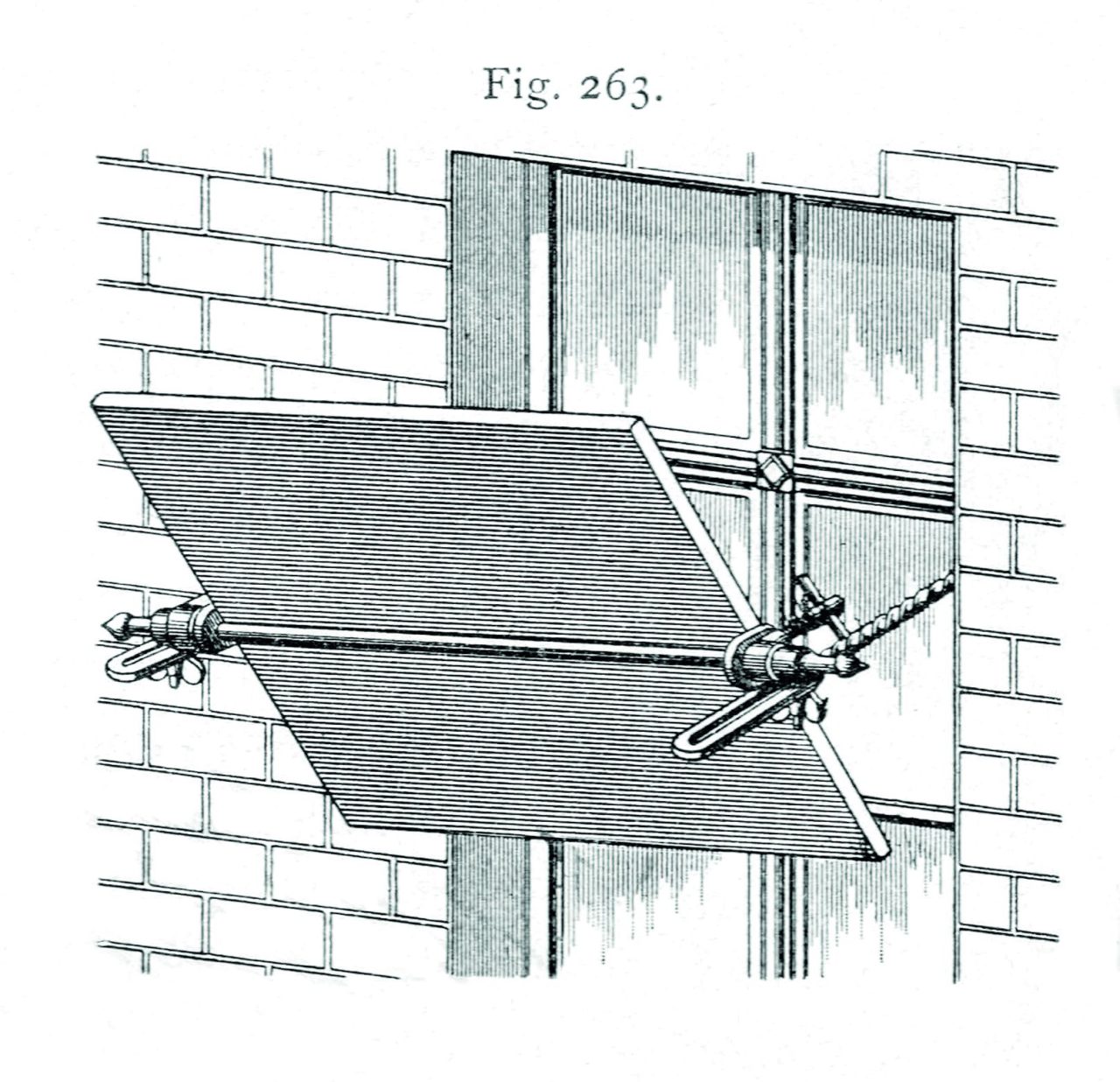

Or this “adjustable reflector”, which was published in a handbook from the late 19th century.

-

Adjustable Reflector, 1896

The mirrored surface of the device reflects the daylight and brings it into the interior.

Why were these reflectors invented?

Quite simply, to offer a technical solution to the problem of the narrow courtyard block, which had been built all over Europe in the overcrowded citycenters of the period. While such devices could not solve problems related to urban density, both inventions worked perfectly as viewing or lighting devices.

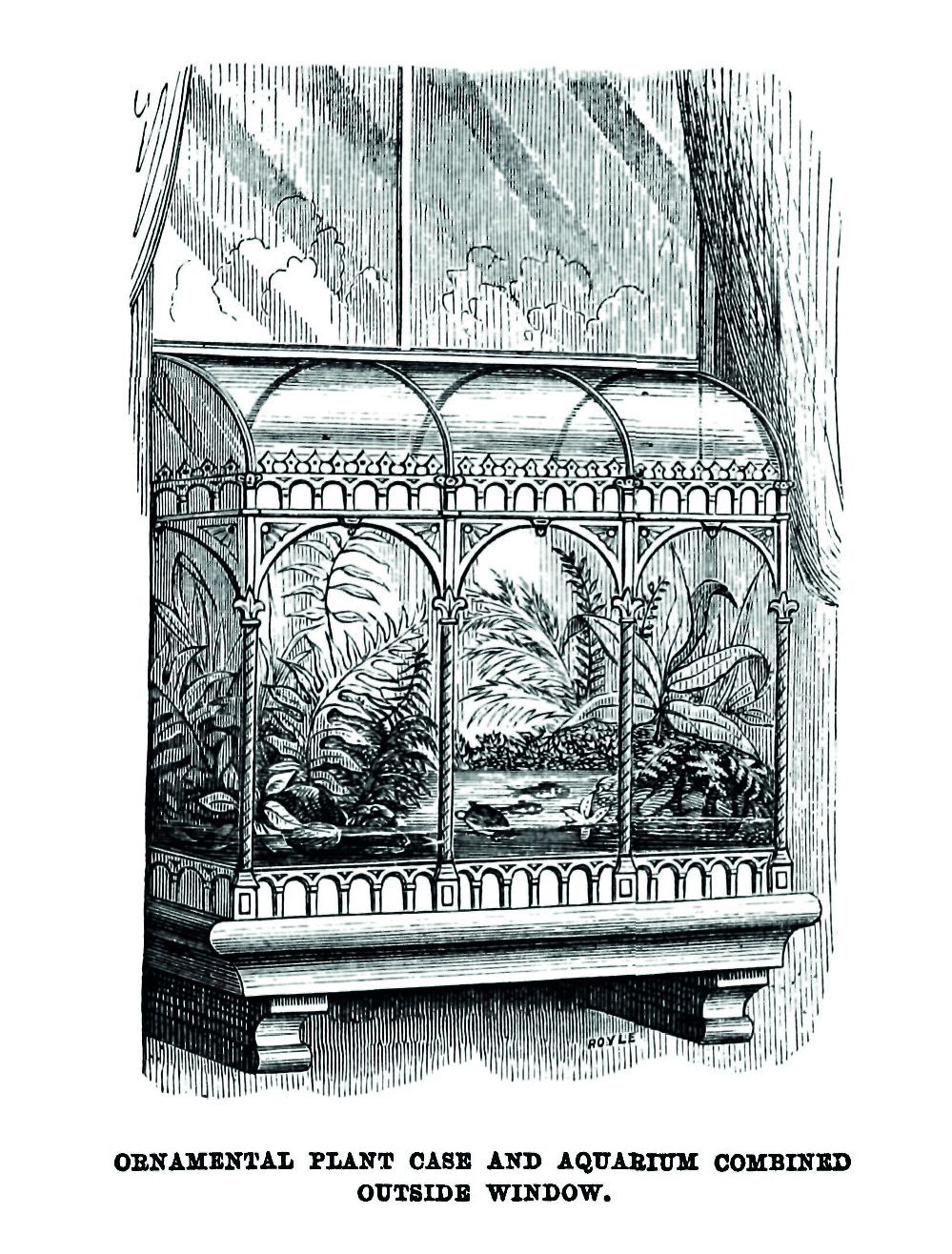

Or take the example of this window-as-aquarium, which tries to take advantage of the specific climatic conditions that exist in the sealed space between two glass surfaces. Here again, while the invention might not have been successful, it does highlight a specific characteristic of the window.

-

Ornamental Plant Case and Aquarium Combined Outside Window, 1877

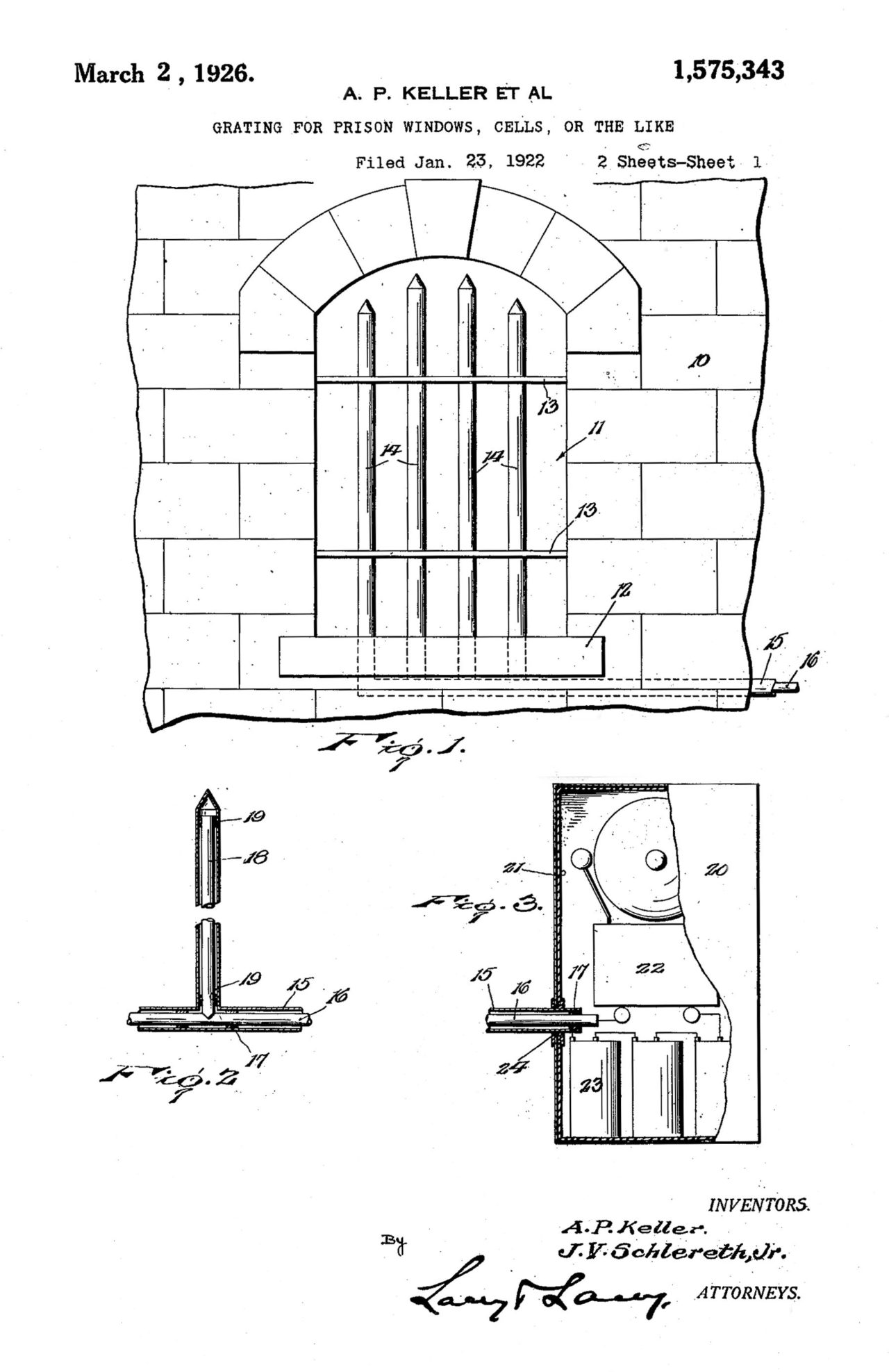

Another example is this patent for an alarm system for the bars of a prison window. Again, this patent points to a central affordance of the window: that of an articulated separation between interior and exterior.

-

Granting for Prison Windows, 1922

A window with a bell system inside the bars.

How did you find these patents?

For the first stage of our research, we systematically went through the American patents, which are easily accessible digitally. We tried to build categories and families of kinship to select the most relevant ones.

Did you develop any further avenues of research?

Naturally, the research we undertook was only the first step. We looked at patents and handbooks only, from the last years of the 19th and the first part of the 20th century. The research can and should be expanded in several directions. Firstly, it could be continued chronologically up until the present. Next, it could be extended thematically, as we focused mainly on the frame of the window, the space of the window, and the devices around it, but not yet on glass technology. Furthermore, I am sure that norms, laws, or even legal cases could tell us a lot about the uses, misuses, and failures of windows and window technologies. Finally, the research could and should be expanded by researching concrete applications, whether in terms of authored architecture or anonymous architecture. All these proposals, however, have the same aim: to understand the conditions and possibilities that underlie the design of windows.

Besides your work as a researcher, you were also one of the curators of the Japan Pavilion “Architectural Ethnography” at the Venice Biennale this year. What was your role there?

-

Installation view of Architectural Ethnography in the Japan Pavilion of 16th Venice Architecture Biennale, 2018 © Andrea Sarti/CAST1466, photo courtesy of the Japan Foundation

The Japan Pavilion was a collaborative work under the curatorship of Momoyo Kaijima. The team comprised Yu Iseki, Momoyo Kaijima and her team, as well as my collaborator Andreas Kalpakci. In particular, we collaborated on specifying what the topic would be, defining the means to represent it, and the selection of architects and artists. While the topic was deeply connected to Momoyo Kaijima’s previous research, the choice to show only drawings stemmed from the fact that both of us were fascinated by this form of architectural representation and its potential. Finally, the choice of contributors was made through a series of working sessions around the series of ca. 120 studies that we had initially selected. But of course, the work of each of us was determined by our individual and different strengths. My team was thus very much engaged in the catalogue, and less in the technical aspects of the curating. Every piece of the catalogue and exhibition went through the hands of the whole team, however. Momoyo has a very open way of working, which benefitted the whole project.

There are drawings by more than 40 participants in the exhibition. How did you approach to the theme?

“Architectural Ethnography” seeks to show how architects, by means of architecture and through the tools of architecture, can analyze today’s living conditions, from the uses of building technology and environmental conditions to legal norms or conventions. The exhibition expands on the one hand the domain of architecture (and its narrow definition as purely building), while on the other hand, this expansion relies on the specificity of the discipline and its tools, especially the drawings. You won’t see any text by the participants, and you won’t see any photographs: only drawings, as drawings are the most immediate tools with which the architects work.

-

Installation view of Architectural Ethnography in the Japan Pavilion of 16th Venice Architecture Biennale, 2018 © Andrea Sarti/CAST1466, photo courtesy of the Japan Foundation

Were any of the exhibited works related to windows?

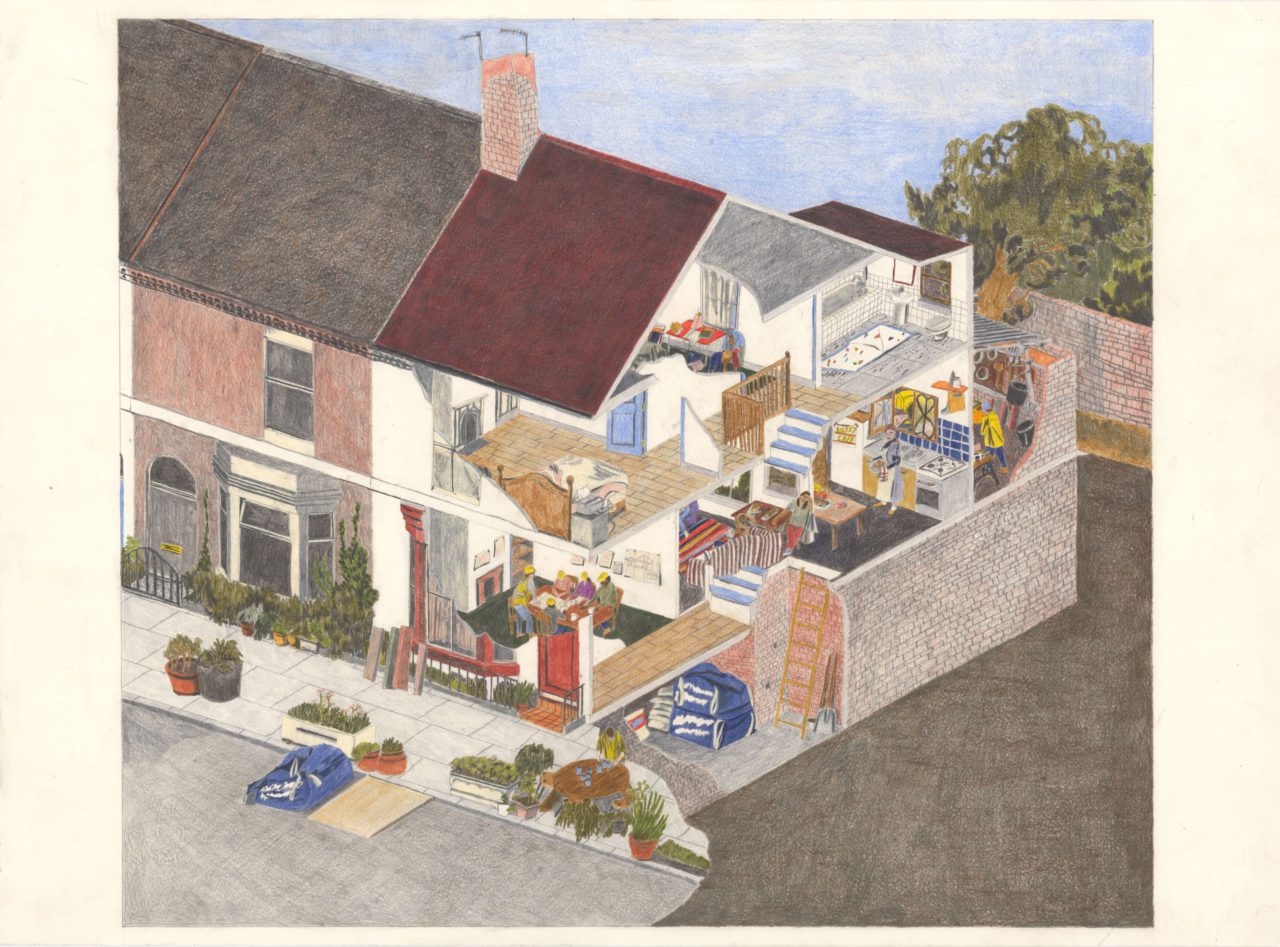

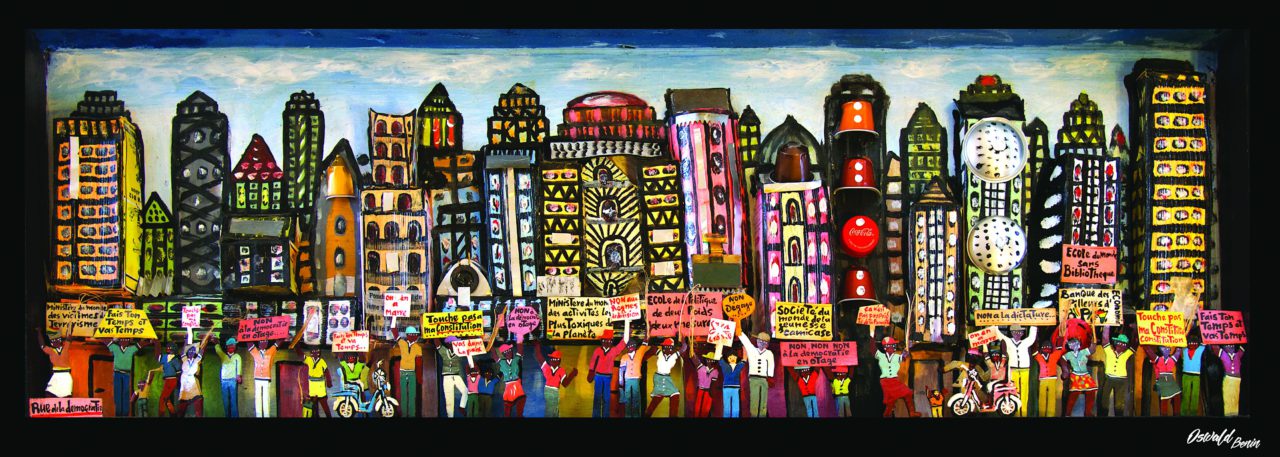

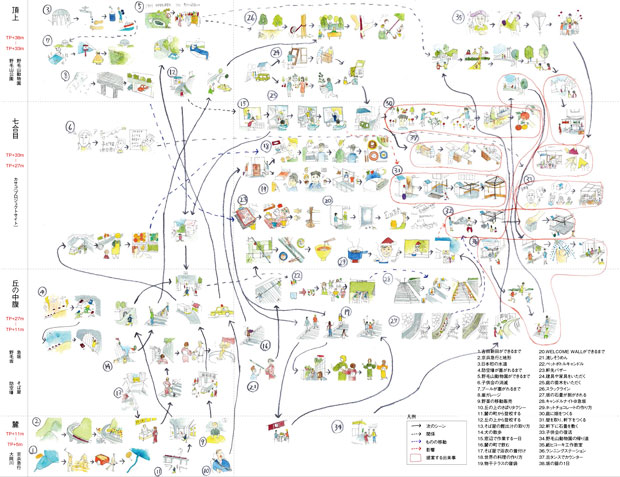

The window is probably one of the elements in which the milieu of a building — that is to say, its conditions such as climate, topography, and conventions — are best reflected. Therefore, even if the window were not central to our research, it is omnipresent. It’s always there, and it pops up again and again, so to speak. It is present as well in a rehabilitation project by the British collective Assemble in Liverpool, just as it is in the politically charged miniature streetscapes by Beninese artist Oswald Adende, or the map depicting the building process by tomito architecture from Japan.

-

A series of sketches related to the preservation and rehabilitation project in Liverpool. Axonometric projection is used here to depict the working and living spaces where the creator resided. Assemble with Marie Jacotey, "Granby Four Streets", courtesy of the Artist and Hannah Barry Gallery, photo courtesy of the Japan Foundation

While in Assemble’s drawing the bow window serves as a typical motif of an English terrace house that simultaneously allows light into the house and enables views up the street, the generic window in Adende’s streetscape reflects the logic of large corporate companies, whose architecture challenges local customs.

-

The artist has miniaturized an African metropolis and contained it within a wooden box. Recycled articles of trash are used in the work to express issues found in African city life.

Oswald Adande, "Revenducations", Courtesy of Oswald Adande, Photo by Stephane Brabant, photo courtesy of the Japan Foundation

-

A drawing created from research for CASACO, an architectural project in which a duplex was turned into a guest house. One can see examples of relationships and connections between different events relating to the structure that take place from the planning stage.

tomito architecture, "Local Ecology Map of CASACO" © tomito architecture

-

tomito architecture, "Local Ecology Map of CASACO" © tomito architecture

In tomito’s map, the architects show how the window serves as an aesthetic device that frames the outside world. Interestingly enough, tomito also depicts a computer screen in front of the window, thus challenging our conventional understanding of the window as the sole “opening” out into the world. The number of these examples could be infinitely expanded. Indeed, much more so than other elements, the window articulates man’s relationship to his environment.

Laurent Stalder

Laurent Stalder is professor of architectural theory at the ETH Zurich. The main focus of Laurent Stalder’s research and publications is the history and theory of architecture from the 19th to the 21st centuries where it intersects with the history of technology. His publications include “Hermann Muthesius: Das Landhaus als kulturgeschichtlicher Entwurf”(2008), “Valerio Olgiati”(2008), “Der Schwellenatlas”(2009), “God & Co. François Dallegret: Beyond the Bubble” (2011), “Fritz Haller: Architekt und Forscher”(2015), “Architecture/Machine” (2017), “Architectural Ethnography” (2018).

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Thresholds between Coexistence and Architecture

25 Jun 2019

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Interview with Tom Emerson, 6a architects

22 Apr 2019

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Liquid Light

12 Oct 2018

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Spaces In Between

01 Oct 2018