Series Exhibition Report: The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Looking at Freespace through the Windows, Part 2

04 Nov 2018

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Interviews

The Arsenale

Rozana Montiel Estudio de Arquitectura

For Mexico-based architect Rozana Montiel, freespace indicates freeing space and actions, or a space for the act of placemaking. She describes architecture as “social construction,” saying: “Beauty is not a luxury, but a basic service that cannot be separated from need and function.”

The installation her studio developed for the Biennale titled Stand Ground is located in the Corderie, or a long colonnaded space that was once used to build ropes for tying up the ships of the Arsenale, which is the ruins of a state-owned shipyard from the Middle Ages. The once-vertical wall of the space is laid on the floor, as if to literally represent Montiel’ s philosophy of design—”change barriers into boundaries.” With the wall’ s arched window also reproduced and laid on the floor, we view instead a projection showing footage of the outside world’ s vibrant everyday life. By breaking the wall vertically separating these spaces, Montiel merges the enclosed exhibition space and the view from its window; the usually vertical window, then, is turned into a flat surface that allows visitors to experience the strange sensation of walking beside it. The full-scale reproduction was built out of recycled Venetian bricks.

Montiel confronts how space changes through the process of creating architecture, and incorporates the following in her practice to create freespace that activates a given place:

1. Search content in context: work with community

2. Convert barriers into horizons: open communication

3. Transform the perception of space: use space creatively

4. Approach the landscape as a prerequisite: recycle existing infrastructure

5. Re-signify the materials: create a sense of place through texture

6. Work with temporality: respond to change in needs over time

7. Believe in beauty as a basic right

-

A live projection of the Venice Canals outside is displayed on the wall / Photo by Sandra Pereznieto

-

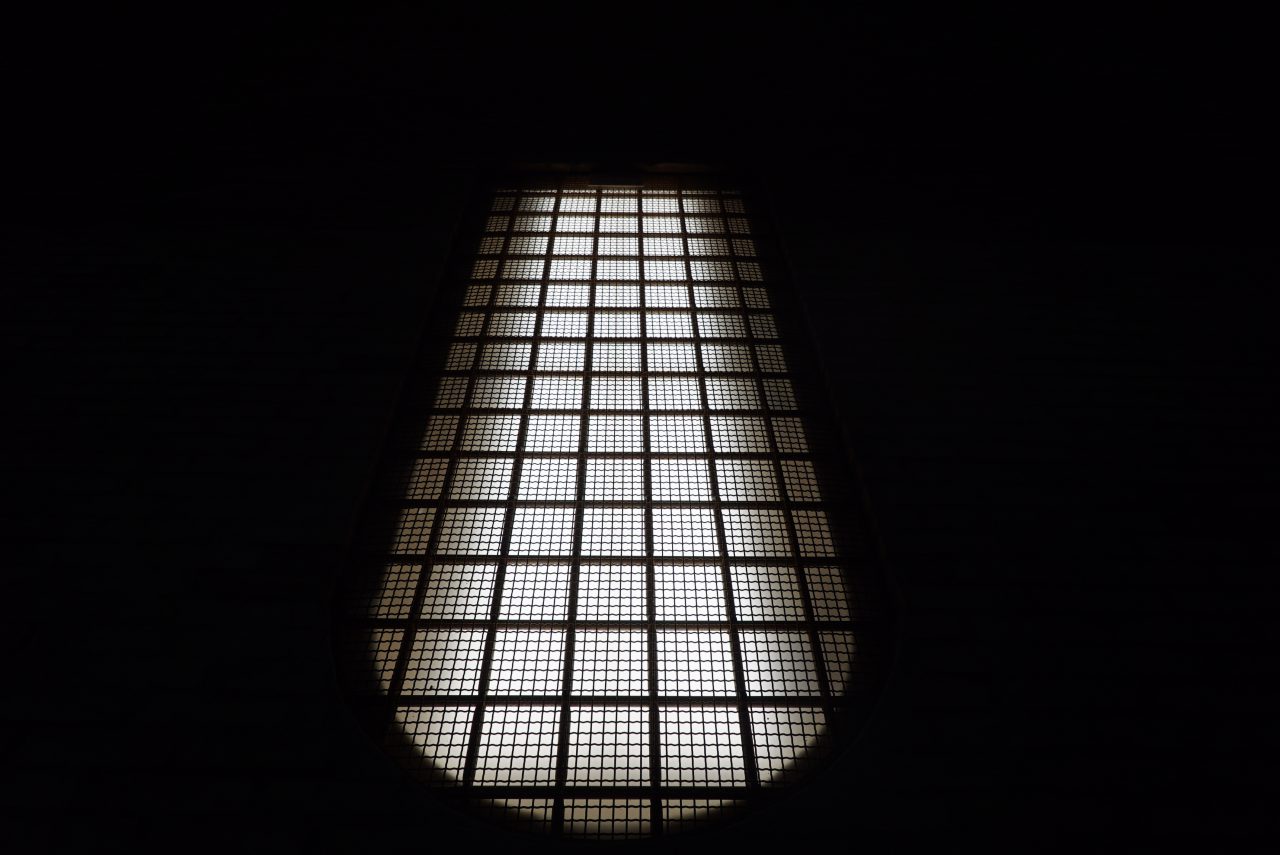

As a former factory, the windows are fitted with iron bars and set at a high position to capture light.

-

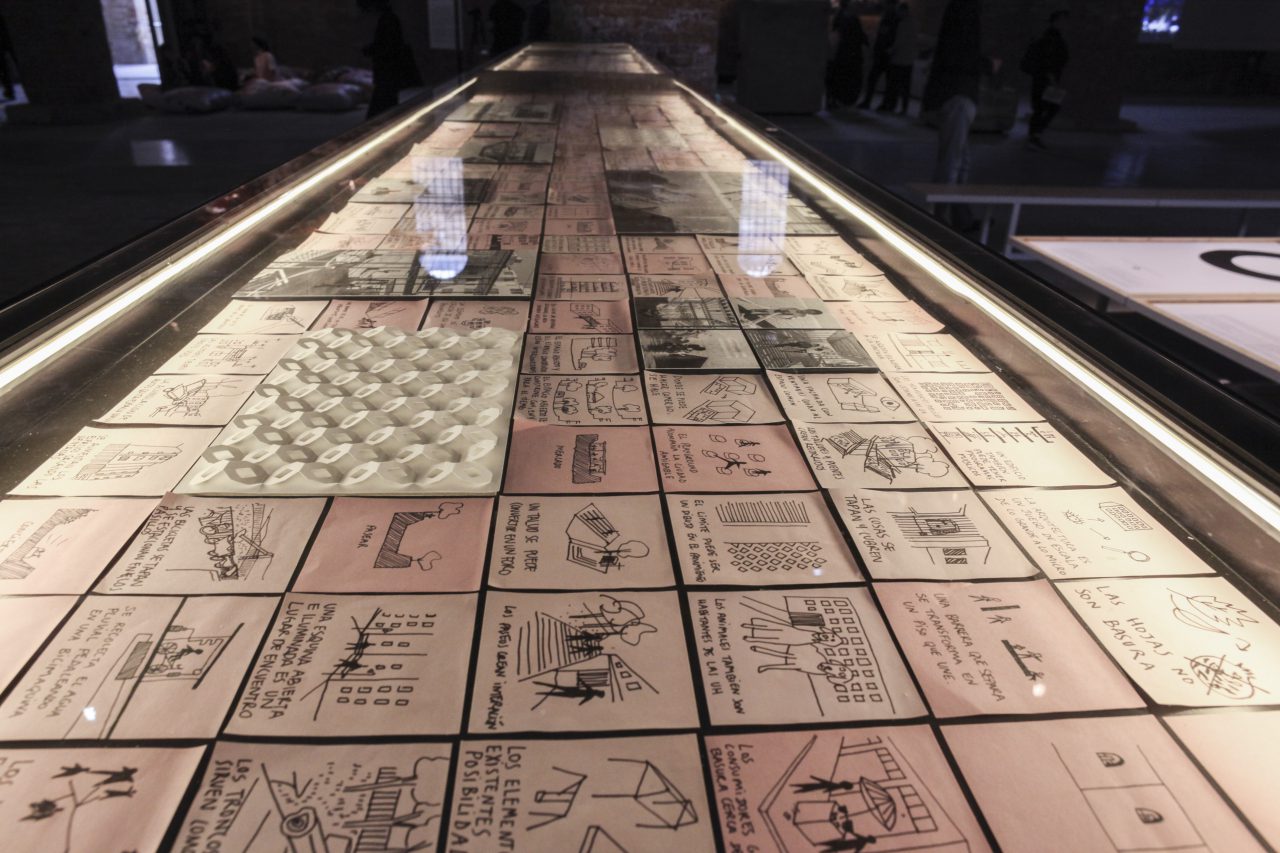

Materials showing Rozana Montiel Estudio de Arquitectura’ s architectural process and methodology, such as their work with public space in social housing projects, are displayed on the table / Photo by Sandra Pereznieto

Dutch Pavilion

Curator: Marina Otero Verzier

Titled “Work, Body, Leisure,” this exhibition explores “the spatial configurations, living conditions, and notions of the human body engendered by disruptive changes in labor ethos and conditions.”

The Netherlands has a history of approaching labor experimentally. Dutch-born artist Constant Nieuwenhuys (1920 – 2005) was a member of the Situationist International, an avant-garde group formed in 1957 in Italy that sought to enact social change through artistic movement. He proposed “New Babylon,” an architectural paradigm of free space and leisure achieved through automation, where society invites creation and play and allows individuals to design their own environments. However, such optimistic views on the joys and possibilities of being liberated from labor through automation eventually fell behind; a more dystopian future of unemployment and inequality is now foreseen due to machines taking human jobs. It has become necessary to redefine the contemporary structure of labor based on new ethical principles.

Curated by Marina Otero Verzier, Director of Research at Het Nieuwe Instituut, this exhibition analyzes space and protocol for human and machines based on the institute’ s long-term research, titled “Automated Landscapes,” which examines the implications of automation for built environments. The institute plans to discuss the issue from the perspective of law, culture, infrastructural technology, and more.

The exhibition’ s walls are filled with locker doors. Lockers are employed as an interface between labor and non-labor as they are used to change into workwear. The doors have architectural typologies written on them such as playground, office, factory, window, or door; inside each, viewers can look into research materials, footage, or spaces beyond the lockers.

-

Orange, a color symbolizing the Netherlands, is used from floor to locker / Photo by Daria Scagliola

-

Inside the #SIMULATION door is Simone C. Niquille’ s installation titled Safety Measures, in which a rubber doll jumps on a black-and-white airbed. The work proposes measuring workers’ safety using digital avatars.

-

Inside the Window door, results are displayed from a joint research project on sex work in the red light districts of the Netherlands, a country where prostitution is legal, led by Amsterdam Museum and a Dutch foundation that studies the social responsibility of robotics / Photo by Naomi Shibata

Naomi Shibata

Born in 1975 in Nagoya, Japan. Naomi Shibata is an editor. After graduating from Musashino Art Universityʼs Department of Architecture, she joined the editorial team of architecture magazine A+U from 1999 to 2006. From 2006 to 2007, she worked at thonik, a graphic design office based in the Netherlands, through the Ministry of Cultural Affairsʼ Program of Overseas Study for Upcoming Artists. Since then, she has worked on editorial design and curation both inside and outside of Japan. From 2010 to 2015, she managed communications for Sendai School of Design (a joint partnership between Tohoku University and City of Sendai). She also served as Assistant Curator for Aichi Triennale 2013. In 2015, she completed a research residency on exhibition facilities in relation to architecture at the Cité internationale des arts. She served as Exhibition Coordinator for YKK APʼs Windowology 10th Anniversary Exhibition: The World Through the Window in 2017.

www.naomishibata.com

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Exhibition Report: The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Looking at Freespace through the Windows, Part 3

20 Nov 2018

Exhibition Report: The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Looking at Freespace through the Windows, Part 1

07 Sep 2018