Vino Santo in Trentino

23 Oct 2018

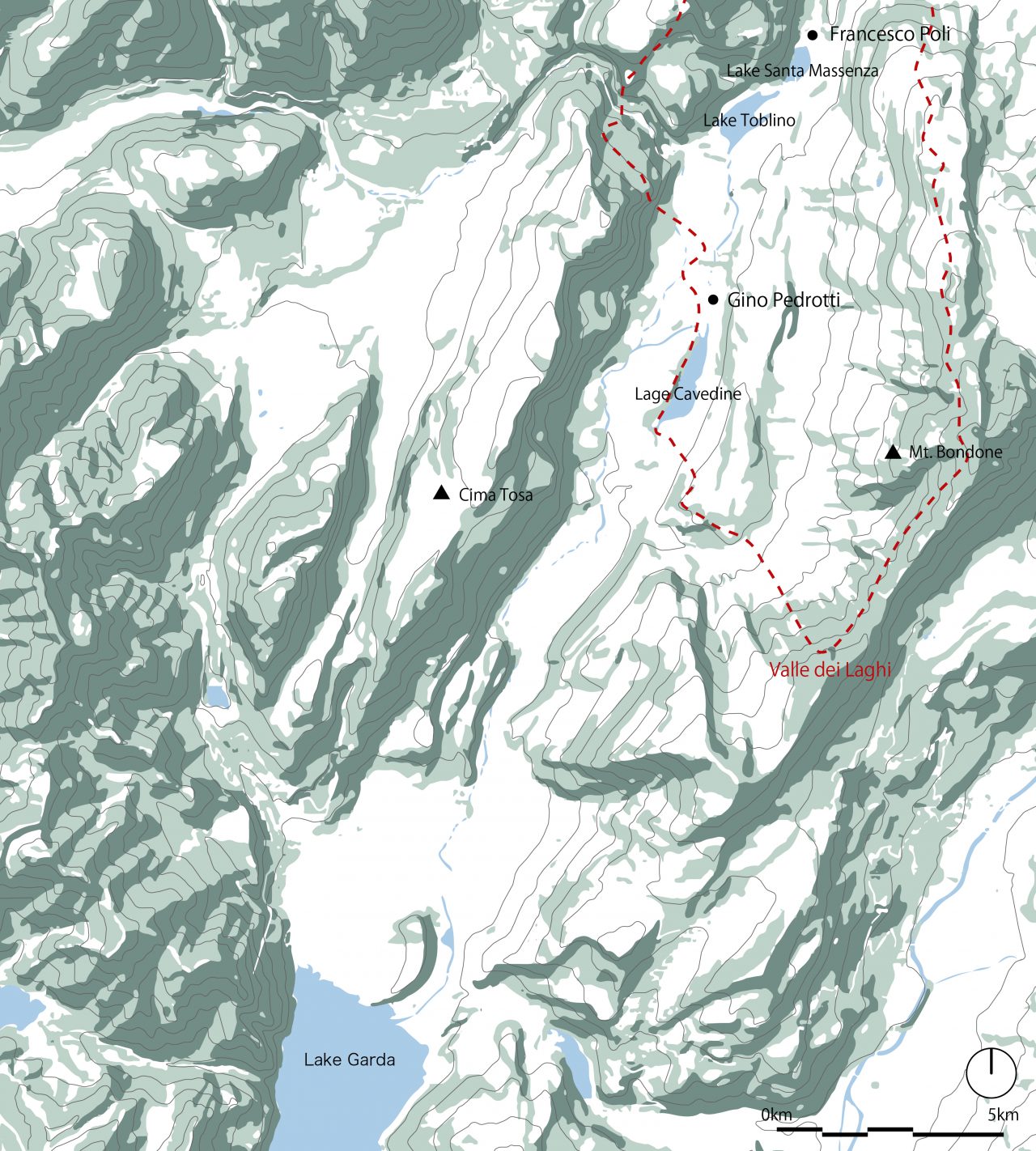

Drive a car east from Milan, go north through Verona and you will see the largest lake in Italy, Lake Garda. Continue running north along the lake and you will arrive in Trentino. This is a province located in Trentino-Alto Adige, at the border with Austria and Switzerland, so both Italian and German are recognized as official languages. Because much of Trentino features valleys lying in between small mountain ranges, the days remain cool even in summer. It is used as a summer resort not only from Italy, but also from neighboring countries, and you can see people enjoying touring and cycling.

For this second column, I would like to introduce the windows that make use of nature to help produce Trentino’s Vino Santo noble rot wine. Noble rot wine is a type of sweet dessert wine made by attaching the noble bacteria (Botrytis cinerea) for fermentation. The bacteria melts the wax layer that protects the surface of the grape and promotes the evaporation of moisture from the fruit. By doing so, the sugar is condensed and a unique flavor can be produced. Noble rot wine is known as a luxurious wine due to its rarity. Generally speaking, it is fermented in vineyards——Trentino Vino Santo, however, is fermented in the attic room. This special production method makes the flavor very mellow.

-

Trentino valley between the slightly elevated mountains

Trentino’s precious wine is called “Vino Santo Trentino, ” which is made up of regionally unique white grapes called “Nosiola.” Wine is still being produced in traditional ways by local producers registered with Slow Food.

There are various opinions concerning the origins of “Vino Santo.” One is a theory that Venetian merchants marked the seal “SANTO” when buying sweet wine from Santorini Island in Greece from the 15th century to the 19th century. Since brewing technology had not yet developed at the time, the wine of the high temperature islands like Santorini was sweet. The wine was said to have gained popularity as it was used for church services for monks, and that it was exported to Italy and even Russia.

Another theory is that Vino Santo was named as a holy (=santo) wine (=vino) that can cure disease. It is said that, because of its healing power, wine that was left over from church services was used as a substitute for medicine.

In the 17th century, when the production of Vino Santo in Trentino began, Trentino was under the control of the Habsburg family (Austria), so much of it was sold in Austrian and German markets. However, when Austria was defeated in World War I and Trentino was integrated into the Kingdom of Italy, its production demand drastically declined. Today, 110-hectare vineyards in Trentino are mostly grown as international Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, and the proportion of “Nosiola”, an inherent species used for precious wine, is said to be only 1.5%.

-

There are couples of small lakes from north to south between the valley in Valle dei Laghi

Of this 1.5%, six groups of producers are registered with Slow Food and are still producing Trentino vino santo using traditional methods. I visited four of these groups. Of them, I would like to especially introduce Gino Pedrotti’s production method.

The Pedrotti family owns small sunlit and airy vineyards along Cavedine Lake that are surrounded by greenery. With these, they are involved in the entire process of grape cultivation and wine production.

“The cultivation of Nosiola requires much more attention compared to other varieties of grapes,” says Pedrotti. “Drainage and ventilation are important.”

-

The winery of Gino Pedrotti

To improve drainage, Pedrotti says that he is making stepped fields in the calcareous sandstone soil. To improve ventilation, he uses a Y-shaped pergola unique to the area, which is composed of square lumber fixed to a concrete column.

-

Y-shaped pergola called "Trentino Pergola" which lets the wind blow well

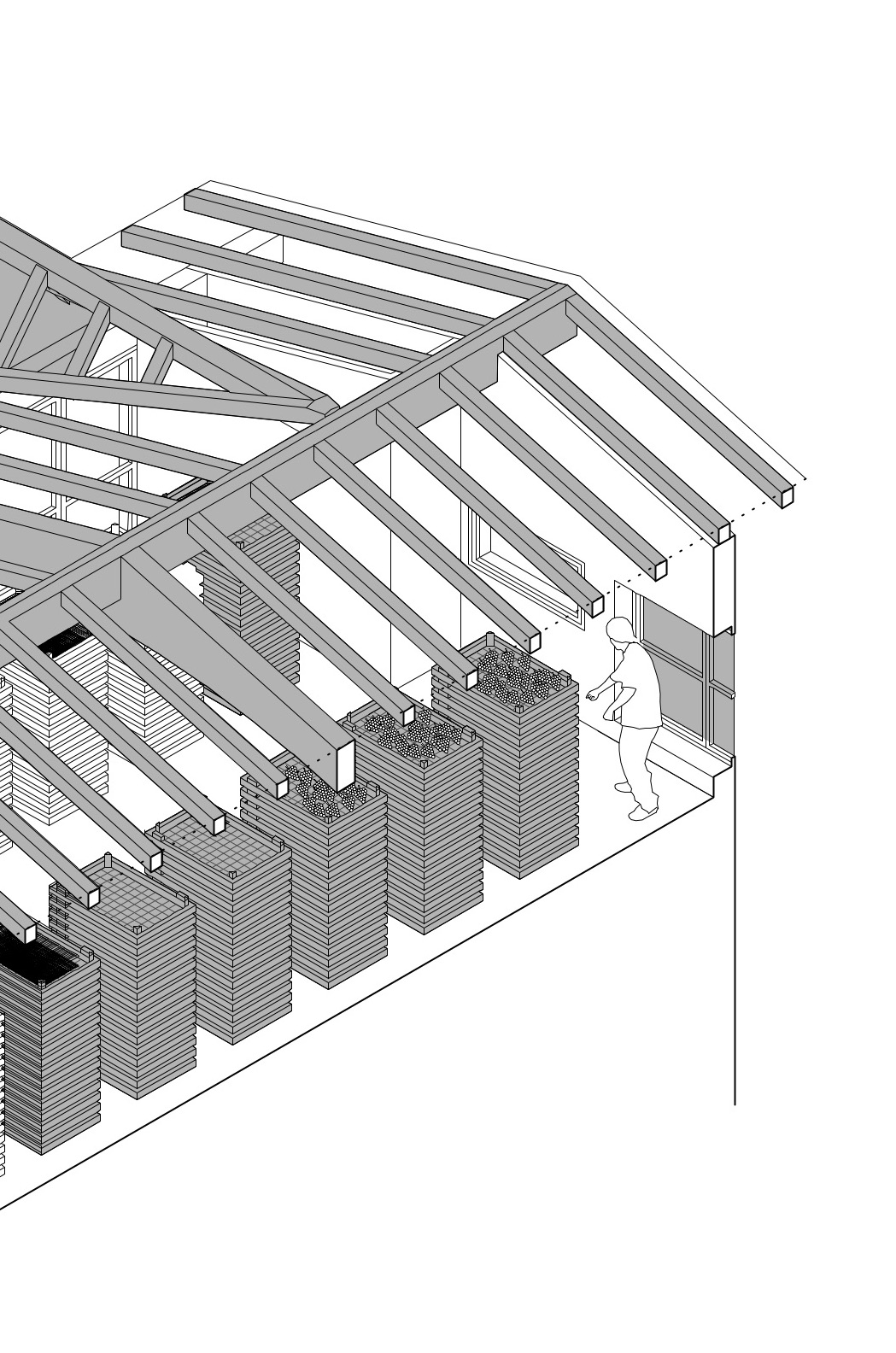

Grapes raised in this manner are harvested after ripening in late September, and are brought into the attic of the winery, in which there is a room for drying. The attic is constructed from a laminated timber frame, and the room’s humidity is kept to 60%. To improve the ventilation, the grapes are placed on a wooden pallet with a wire mesh.

“We open the windows of the attic from September to November, in order to let in the wind blowing from Lake Garda. The wind blowing from the temperate Po Valley to the north picks up moisture as it passes through Lake Garda, passes through the valley and comes here. In this way, we can encourage fermentation using bacteria while simultaneously drying the grapes. We call this wind “Ora del Garda” (Garda’s Time).”

-

Attic room from drying and fermentation

In this way, wind and the bacteria necessary for fermentation are blown into the attic. After exposure to “Garda’s Time” for two months, Nosiola turns into a “Vino Santo Trentino,” a noble rot wine with a sweet, distinctive flavor.

Looking at the arrangement of windows in the attic, hopper windows are arranged in the center of the room, and the east side is lined with large double French windows.

-

Double door windows which opens during "Ora del Garda"

-

The windows on the east side are only opened when ventilation is bad.

I went back in history a bit, examining literature on the drying/fermentation rooms of Trentino’s noble rot wine production. As can be seen in a photograph from a document published in the 1920s, large and small double-French windows are arranged between columns. Grapes are lain on straw set within a wooden frame, drying in the wind that comes through the windows. Elements of the local climate, topography and architecture are summed up in the phrase, “Garda’s Time”—local seasons, temperature, humidity the positioning of windows. This is evidence for how Trentino’s noble rot wine production method is preciously passed from generation to generation.

I visited the drying/fermentation room of Francesco Poli, who is also producing the same Trentino Vino Santo. Indeed, his room is also located within a timber-framed attic. Double-French windows are arranged along the south side, and in the middle of the room, grapes can be seen drying on wooden frames.

-

Drying and fermentation room of Francesco Poli

After November, when “Ora del Garda” has finished blowing, all the windows that had been fully open are closed, except for the center in-swinging hopper windows. These are kept open for ventilation. The grapes are left to dry in the attic over the next several months until Easter, which lasts from the end of March to the end of April of the following year. About 80% of water is lost from the dried grapes, and the sugar content increases. It is said that 100 kilograms of grapes are needed to make 15 kilos of wine.

When I visited around November in the previous year, water still remained, but the white grapes were gradually beginning to lose water. Held up to the light, the grapes seemd to have an amber color and were very beautiful.

-

The grape in the process of drying and fermentation

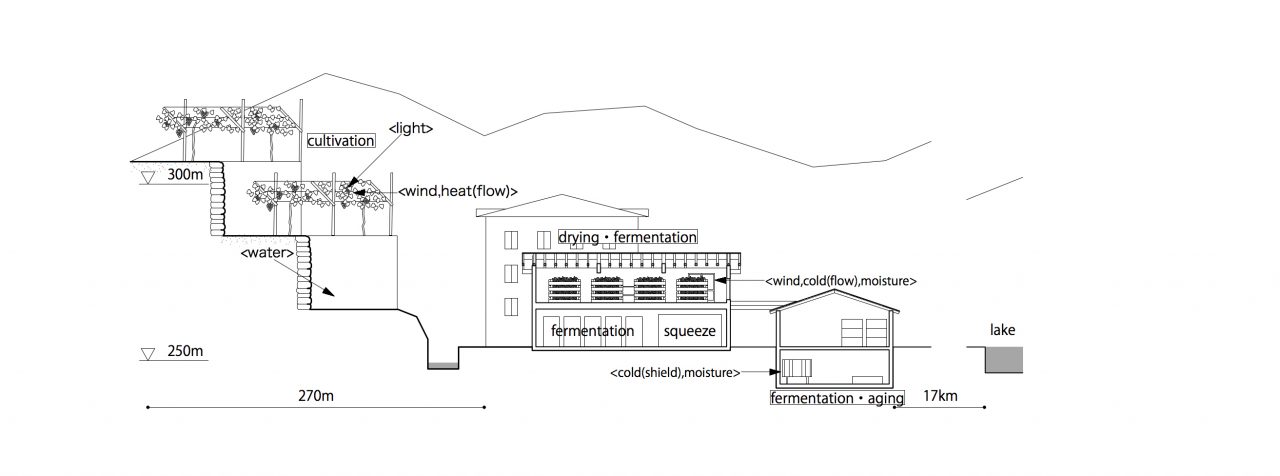

After that, the grapes are squeezed, fermented and aged for six to seven years in oak barrels underground. A concrete aging room helps maintain constant temperature and humidity by utilizing underground cold air and humidity.

-

Underground room manages the resource of coldness and humidity

The wine thus made has a color similar to the color of the oak barrel. The taste is mellow, and scents of honey, raisins and hazelnut spread all over mouth. The name of this variety, “Nosiola,” is said to be derived from the Italian word “nocciola,” meaning hazelnuts. It goes well with biscotti, Italian biscuits that are made with almonds.

-

Noble rot wine "Vino Santo Trentino"

Vino Santo Trentino production process

-

Isometric view of drying and fermentation room

-

The valley section

In Trentino, grapes are cultivated in the valleys surrounded by mountains, so as to avoid the cold windows blowing in from the surroundings. Y-shaped pergolas are arranged east-west in order to improve the movement of warm winds from the south; and, using windows in the attic, the drying and fermentation of grapes is carried out with the help of a moisture and bacteria-carrying wind called “Ola del Garda.” After that, making use of the cold air and humidity of a concrete basement, further fermentation and maturation is carried out.

Tomoki Shoda

Born in Chiba Prefecture in 1990. Since his father transferred to many counties, he had lived in many places such as France, Indonesia, China and Belgium. Researched about traditional workshops in Japan for “WindowScape3 -working window” in Yoshiharu Tsukamoto Laboratory at the Tokyo Institute of Technology from 2014 to 2015. Studied abroad in Politecnico di Milano from 2016 to 2017. Researched about Italian Traditional food registered by Slow Food from the perspective of architecture. Graduated master course in Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2017. Researched Japanese Traditional food production as Slow Food Nippon researcher from 2017 to 2018. He has been in Takenaka corporation design team from 2018 to present.