01 Oct 2018

- Keywords

- Art

- Arts and Culture

- Interviews

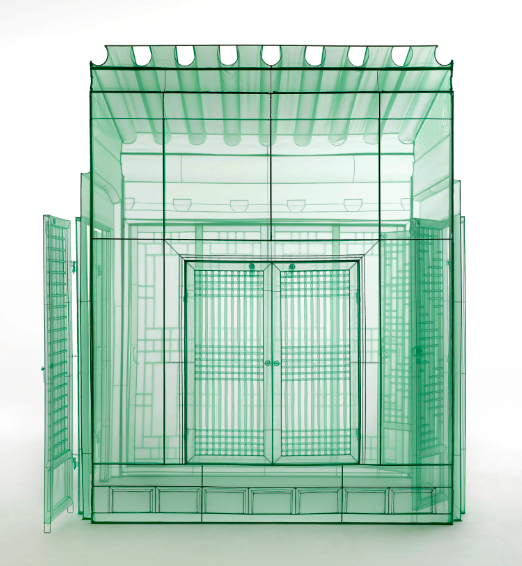

Korean artist Do Ho Suh, who is perhaps best known for his translucent fabric recreations of real buildings, has continued to explore the relationship between existence and space through his work. In 2018, he unveiled a new piece titled Robin Hood Gardens, Woolmore Street, London E14 0HG at at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2018. The film piece, which captured the Robin Hood Gardens (1972) ahead of its imminent demolition, not only brought into light the memories and lifestyles embedded in the concrete living units of the apartment complex but also helped us understand the influence traditional Korean living spaces and windows have had on Suh’s work.

For years you’ve been engaged with creating fabric sculptures, but you decided to make a film for the Biennale. What was the reason for this?

My initial proposal was to make a fabric piece. However, because the apartments were about to be demolished and were soon going to disappear, it became more important for me to document their interiors than to create fabric versions of them. That can be done any time later.

How did you go about the filming process?

We started by asking residents if they could open their doors to us. The Victoria and Albert Museum, which commissioned the project, managed to secure one unoccupied unit and three occupied units. It took us a whole day to film each occupied unit and maybe two or three days for each unoccupied unit.

We documented the spaces using time-lapse 3D scanning and photogrammetry. With this very straightforward documentation process, we were able to capture not only the physical building structure but also the intangible qualities of the people’s homes—like the accumulated energy or history in the spaces.

As you can see in the film, the residents put their own things inside when they moved in, so each unit is radically different. I wanted to show what the units looked like with these layers of things in them and before everything was there. Because these weren’t my own homes and I never actually lived in them, I got to know the apartments better through the filming process.

-

First photo: Video still from Robin Hood Gardens, Woolmore Street, London E14 0HG by Do Ho Suh . Courtesy of the artist, Lehmann Maupin, New York Hong Kong and Seoul and Victoria Miro London / Venice © Do Ho Suh | Second photo: Taegsu Jeon, Do Ho Suh: Passage/s, 1 February – 18 March 2017 Victoria Miro Gallery II, 16 Wharf Road, London N1 7RW Courtesy the artist, Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong and Seoul, and Victoria Miro, London / Venice © Do Ho Suh

-

Robin Hood Gardens, Woolmore Street, London E14 0HG by Do Ho Suh commissioned by the V&A. Courtesy of the artist, Lehmann Maupin, New York Hong Kong and Seoul and Victoria Miro London / Venice. Photo by Window Research Institute

Usually, you make pieces based on spaces that you once occupied, but this time you made a film while working with homes that you had no personal connection to. Did these differences change how you approached the project?

Yes, it was very different this time. First of all, it took me until after the filming was done to figure out the logic of the architecture because it was built on a very complicated modular system. I had to try to understand the logic of its design through the lens of the camera, which essentially caressed all the surfaces of its spaces.

In a way, I suppose I approached the project similarly to my other work, as it was also about being very observant and paying attention to every single square inch of the spaces. As for the time-lapse technique, that wasn’t just a fancy effect—it was actually very appropriate for the project conceptually because it let me capture many more frames than regular film.

We could’ve just filmed in each unit with a video camera for maybe a couple of hours, but we instead spent a whole day to take hundreds of thousands of still photographs that we then stitched together on the computer to create time-lapse animations.

It appears that you combined the time-lapse animations with footage shot at normal speed so that the people and backgrounds are moving at different speeds.

Yes, there were different kinds of filming involved. We filmed the scenes without people and filmed the people separately, and then we put them together because we needed to control the time in two different ways.

You may notice that the figures become transparent as they walk out of the frame. We had to film twice in order to do that, and that sort of elongated the filming process. The conceptual reason why we filmed using such a time- consuming process was that I wanted to respect the time lived there by the residents, as most of them had been living in the single spaces for more than 40 years.

I didn’t feel like we should just go in and then quickly be done. And then, of course, after that there was the post-production work, which took a couple of months to complete. Honestly, I wish I had more time because we got a massive amount of scanned data that I think I could’ve played with to make very interesting things.

-

Photo by Moe Onishi, Window Research Institute

The film contains many iconic shots of windows from beginning to end. What did you find interesting about them?

When I first visited Robin Hood Gardens, I discovered that the living rooms in every unit were all identical, even though the modules were different. Alison and Peter Smithson, the architects, reinforced the repetitive, standardized structure of the apartments with the layout of the windows. In order to show this, I positioned the camera parallel to the façade and moved it horizontally and vertically to follow the grid system.

You can see that all the shots show people in rooms that are decorated differently but have the same windows. You don’t see the similarity unless you look closely because many of the rooms have been personalized with curtains and such, but if you take a careful look you can recognize the repeating structure. To articulate this, I chose to shoot the scenes systematically instead of artistically. Anything you see captured through the windows, though, just happened to be there.

In some of the scenes, there were things that even we didn’t know we filmed. For example, you can see an airplane and cars and such. I didn’t see those things until I projected the film onto a big screen. You could say the windows acted as camera frames that revealed those uncanny moments and things beyond the building. That was an interesting discovery.

-

Robin Hood Gardens, Woolmore Street, London E14 0HG by Do Ho Suh commissioned by the V&A. Courtesy of the artist, Lehmann Maupin, New York Hong Kong and Seoul and Victoria Miro London / Venice. Photo Copyright © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

It’s interesting that you say that, because, in a way, windows reveal things by their very nature as things that occupy a place in between the inside and outside.

I grew up in a very traditional Korean house, which was somewhat similar to a traditional Japanese house for how it didn’t define a clear difference between the inside and outside. Traditional Korean houses don’t have large walls and consist mostly of doors and windows, so they’re very different from Western houses, which instead contain totally controlled, artificial spaces separated from nature and their surroundings.

Traditional Korean buildings have walls that are more porous, and they’re permeable because they tend to have more doors and windows. They’re almost like air. They breathe and bring in the sounds, smells, and light from outside, so even when you’re in the house, you still feel like you’re out in nature. That was the environment I grew up in.

I don’t believe that kind of environment came to be by accident; it was created intentionally. I think it reflects the way Korean people wanted to see the universe. A lot of traditional Korean houses also have large yards that are separated from the neighbors and public spaces by very low walls, so you have to pass through many different spaces in order to reach your room from the gate. They also contain many in-between spaces, which don’t exist in most Western houses.

Traditional Japanese houses also have similar in-between spaces. For instance, there is the engawa, which is a perimeter space that connects the inside and outside of a house like a window, and you can also sit in it to enjoy the scenery.

That’s right. Speaking of scenery, the siting of houses in Korea is very important, partly because the houses have many doors, windows, and those in-between spaces, and partly because of feng shui.

When Korean people design houses, they begin by picturing an imaginary window to frame the landscape. So people will already have a very specific window in mind before construction even begins. You’ll often have a prime view of the surroundings from that room, which will usually be used as the master’s study.

Western cultures tend to value the individual more compared to Eastern cultures so they tend to be very clear about defining personal spaces. These spaces are more fluid in Asia and especially in Korea. So I guess you could talk about the differences between our philosophies based on our concepts of windows.

-

Hub, 260-10 Sungbook-dong, Sungbook-ku, Seoul, Korea, 2016. Courtesy the artist, Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong and Seoul, and Victoria Miro, London / Venice (Photography Taegsu Jeon) © Do Ho Suh

-

Seoul Home/Seoul Home/Kanazawa Home, 2012. Courtesy the artist, Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong and Seoul (Photography Taegsu Jeon) © Do Ho Suh

Would you say that your fabric architectural pieces also embody these aspects of Korean culture that you grew up with?

Definitely. My fabric pieces are reconstructions of spaces that are very intimate and personal to me. So actually I’m asked all the time how I feel about installing them in museums, because by doing that, all of a sudden everybody can enter and look at my personal spaces.

-

New York City Apartment/Corridor/Bristol, 2015. Courtesy the artist, Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong and Seoul, Victoria Miro, London /

Venice and Bristol Museums, Galleries & Archives (Photography Jamie Woodley) © Do Ho Suh

When you look at the pieces, you don’t always realize if you’re on the inside or outside because the walls are all transparent. Even if someone is facing you, you don’t know if you’re being watched, either.

The Korean house I was brought up in also had such blurry boundaries, and the sounds, smells, and air could pass through it. That’s why I don’t think of that house as a purely personal space—it was something between a personal and public space. All of us have different concepts of public space and personal space, so people will probably define the space differently.

I think Korean architecture was developed based on Confucianism, so people know they have to behave even when nobody is watching. You know that you’re not completely isolated and that people can hear everything, so you have be aware of this.

In a way, you always have to think about yourself in relation to others. I don’t actually know whether this way of thinking influenced the design of Korean buildings or vice versa, but it seems to me that way of living somehow dictated the architecture.

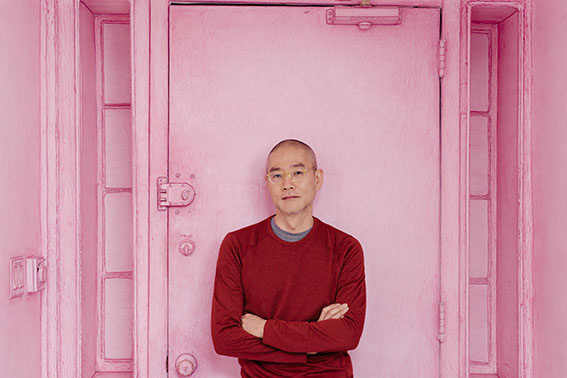

Do Ho Suh

Do Ho Suh (b. 1962, Seoul, Korea; lives and works in London, New York and Seoul) works across various media, creating drawings, film, and sculptural works that confront questions of home, physical space, displacement, memory, individuality, and collectivity. Suh is best known for his fabric sculptures that reconstruct to scale his former homes in Korea, Rhode Island, Berlin, London, and New York. Suh is interested in the malleability of space in both its physical and metaphorical forms, and examines how the body relates to, inhabits, and interacts with that space. He is particularly interested in domestic space and the way the concept of home can be articulated through architecture that has a specific location, form, and history. For Suh, the spaces we inhabit also contain psychological energy, and in his work he makes visible those markers of memories, personal experiences, and a sense of security, regardless of geographic location.

Photo: Daniel Dorsa Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London / Venice All © Do Ho Suh

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Thresholds between Coexistence and Architecture

25 Jun 2019

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Interview with Tom Emerson, 6a architects

22 Apr 2019

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Windows: Openings and devices

12 Dec 2018

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Liquid Light

12 Oct 2018