Series Study on Hashirama-Sochi; Equipment In Between

Movie "THE CORALLUM"

10 Jul 2018

movie “THE CORALLUM”

“Hashirama equipment” is a term used for cultural assets and refers to the entire architectural components between pillars. Specifically, the hashirama equipment includes a variety of types of fittings such as walls, shoji and fusuma sliding doors. In buildings with a wooden framework, in addition to the fittings, the boards and tatami mats on the floors and ceilings are also basically composed of similar “equipment-style” thoughts. A richness of space in Japanese architecture has been created by the diversity of the hashirama equipment. In this study, a building from Japanese architectural history is examined based on a key concept of the previously stated “hashirama equipment”.

A naturally-made space called “ma” (in-between) exists in Sefa Utaki, a historical ritual space in Nanjo City, Okinawa. People sensed an extraordinary atmosphere there, and regarded the space as sacred. The huge rocks are made of Ryukyu limestone (i.e., corallite), formed by coral reefs during the Pleistocene. The Ryukyu limestone formed the entire island of Okinawa, and constituted the city over time while changing its form as foundation stones for traditional houses, or as a material for concrete that supported modernization. This video, “THE CORALLUM”, explores this historical transition, in an attempt to get a brief glimpse of the emergence of the hashirama equipment.

Text content−Dawn of Architecture−

<Introduction>

<Overview of Sefa Utaki>

<Formation of Sangui and Rituals>

<Foundation of Ryukyu Limestone>

<Introduction>

Sefa Utaki is Okinawa’s unique sacred area, located in Nanjo City in Okinawa. Utaki have been important religious bases for village rituals since ancient times. These sacred areas are typically located in a mountain or forest near villages. Utaki characteristically have a widely open space, which were described by Taro Okamoto (1911-1996) – a representative artist of modern Japan, who had a great interest in primitive art – as “dizziness from no existence”.

Sefa Utaki, in particular, has a triangular-shaped tunnel-like opening consisting of huge Ryukyu limestone pieces. It is the most symbolic space for worship. Designated as one of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites, many worshippers still come to Sefa Utaki today, where the ancient worship has been handed down to the present.

This is a prologue of the “hashirama equipment”, about the time before the hashirama equipment was created by human hands, when humans found special places. We focused on ancient sacred places in Okinawa, including Sefa Utaki. Our theme here is Ryukyu limestone, which has been continuously used for everything from traditional houses to modern cities.

<About Sefa Utaki>

Sefa Utaki is located on the east side of the Chinen Peninsula in Nanjo City, Okinawa Prefecture.

In Okinawa since the time of the Ryukyu Kingdom, the east has been considered a holy direction from where the sun rises, called “agari“. The entire area of current Nanjo City and Yonabaru Town was called “agari-kata” and considered a sacred area of the kingdom. Specifically, Nanjo City was a center of the Okinawan legend “Ryukyu Kaibyaku”, and many sacred places still remain today, such as Kudaka Island – an “island of gods”.

Sacred area of the kingdom – Sefa Utaki –

Sefa Utaki is a forest encompassing six sanctuaries, called ibi. A king and the highest ranking priestess of the Ryukyu Kingdom, named Kikoe-no-okimi, took the trouble to visit Sefa Utaki by themselves, and performed various national rituals to wish for bumper crops, national security, prosperity of descendants, and safe navigation for the kingdom. Above all, Sefa Utaki was the main venue of “Oaraori” – the inauguration ceremony of a succeeding Kikoe-no-okimi. It was the most important ceremony for the Ryukyu Kingdom, where priestesses were at the center of the rituals. Kikoe-no-okimi obtained the spiritual power of gods at Sefa Utaki, and protected the king as a living god, “arahitogami“.

Three out of six ibi in Sefa Utaki – Ufugui, Sangui, and Yuinchi – consisting of huge Ryukyu limestone pieces, are believed to be named after rooms and sanctuaries that once existed in Shuri castle1. Sefa Utaki was the most highly regarded sacred area of the Ryukyu Kingdom, where priestesses had political power based on religious authority.

<Formation of Sangui and Rituals>

Formation of the gap in Sangui

The most imposing place in Sefa Utaki is Sangui.

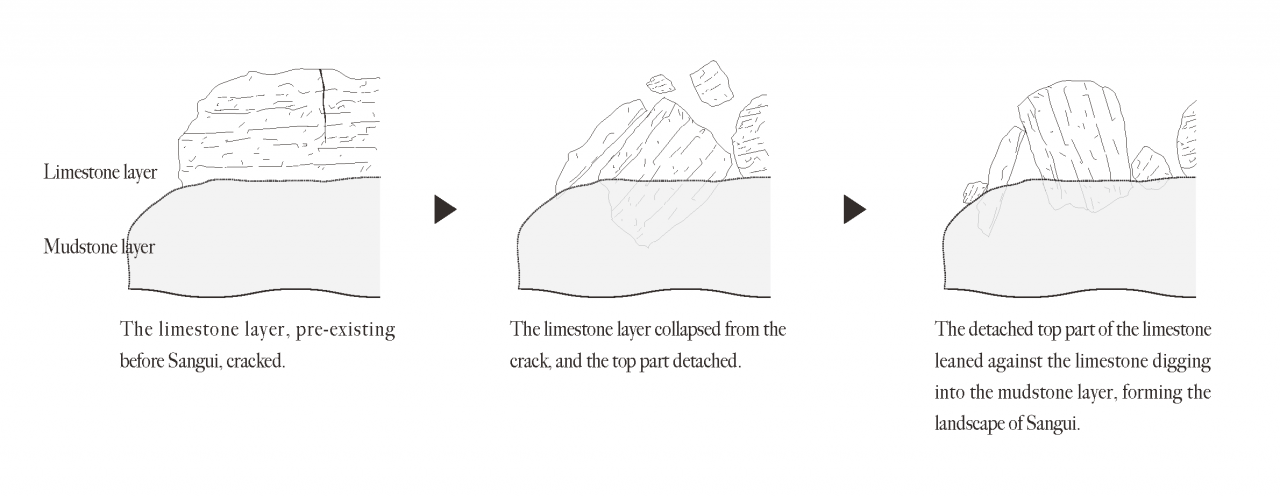

The triangular tunnel-like landscape of Sangui consists of a huge piece of Ryukyu limestone, which seems to have slid off and become embedded while leaning against another huge rock. How was this landscape formed?

The geological base of Sefa Utaki is mudstone strata. The top part is covered with a Ryukyu limestone layer formed in a different time period. The rock once constituting Sefa Utaki was larger than the present one, and formed a rock shelf with a horizontally layered geological structure. Later, the rock shelf collapsed and the largest rock dug into the topmost mudstone layer in an 83 degree angle. The topmost part of the huge rock detached, and came to a stop by leaning against the original rock, creating the triangular gap of Sangui.

-

Figure 1. Diagram of Formation of Sangui

Gap and Rituals

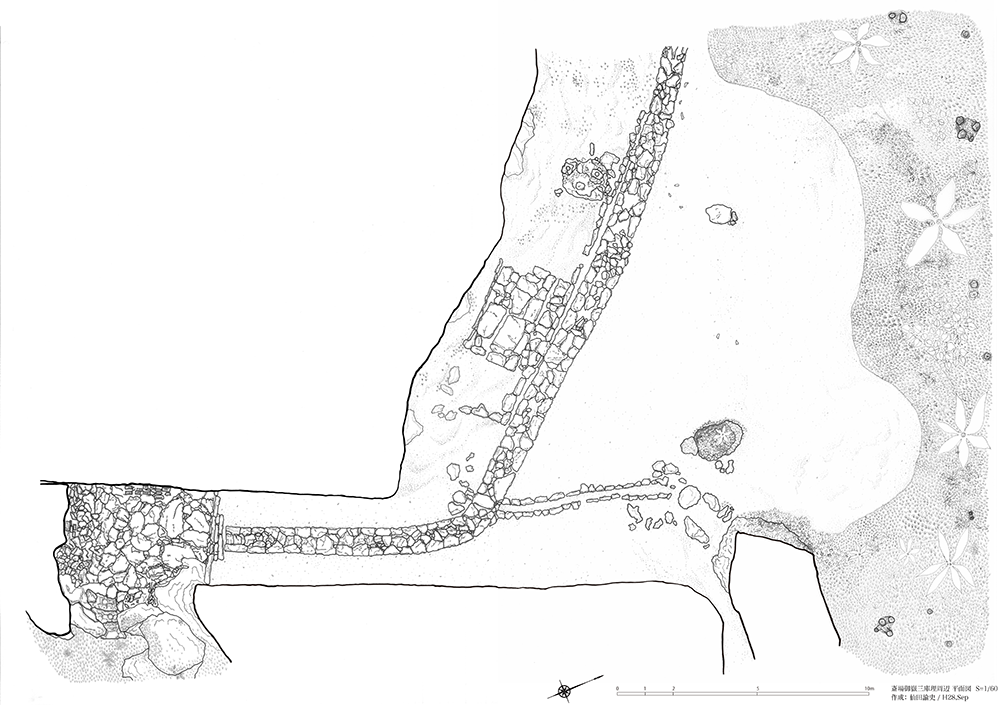

Sangui is one of the important places for rituals performed in Sefa Utaki. The gap of Sangui, consisting of two huge rocks, lays in the north-south direction and is constantly windy. A platform paved with Ryukyu limestone exists behind the gap, and this is where the Ibi of Sangui is. Items likely used for rituals in the Ryukyu Kingdom, such as comma-shaped ornamental stones and coins, have been excavated from under the foundation. The ibi of Sangui became a yohaijo (a place to worship from a distance) for Kudaka Island, as the island can be viewed from there. Kudaka Island is an isolated island, located about 5km east of Sefa Utaki. It is also called the “Island of gods”, and still preserves major sacred areas of the Ryukyu Kingdom, such as Fubo Utaki and Ishiki beach. The rising sun (teida) can be viewed from Ishiki beach on the east side of the island. People in Okinawa believe a paradise called the “Niraikanai” lays beyond the beach. Since ancient times, Sefa Utaki and Kudaka Island have evolved a close relationship. Kudaka Island has been worshipped from the yohaijo in Sefa Utaki, priestesses from Kudaka Island participated in rituals in Sefa Utaki, and coral sand from the island was used for paving Sefa Utaki.2

At the back of Sangui, songs of gods were chanted, which meant setting off to Kudaka Island. The route from reentering the triangular gap of Sangui to Ufugui recreated the visionary journey to Kudaka Island and Niraikanai. Therefore, the gap of Sangui was truly a gate connecting this world to the paradise Niraikanai in the Oaraori ritual.

-

Figure 2. Plan of Sangui in Sefa Utaki

<Foundation of Ryukyu Limestone>

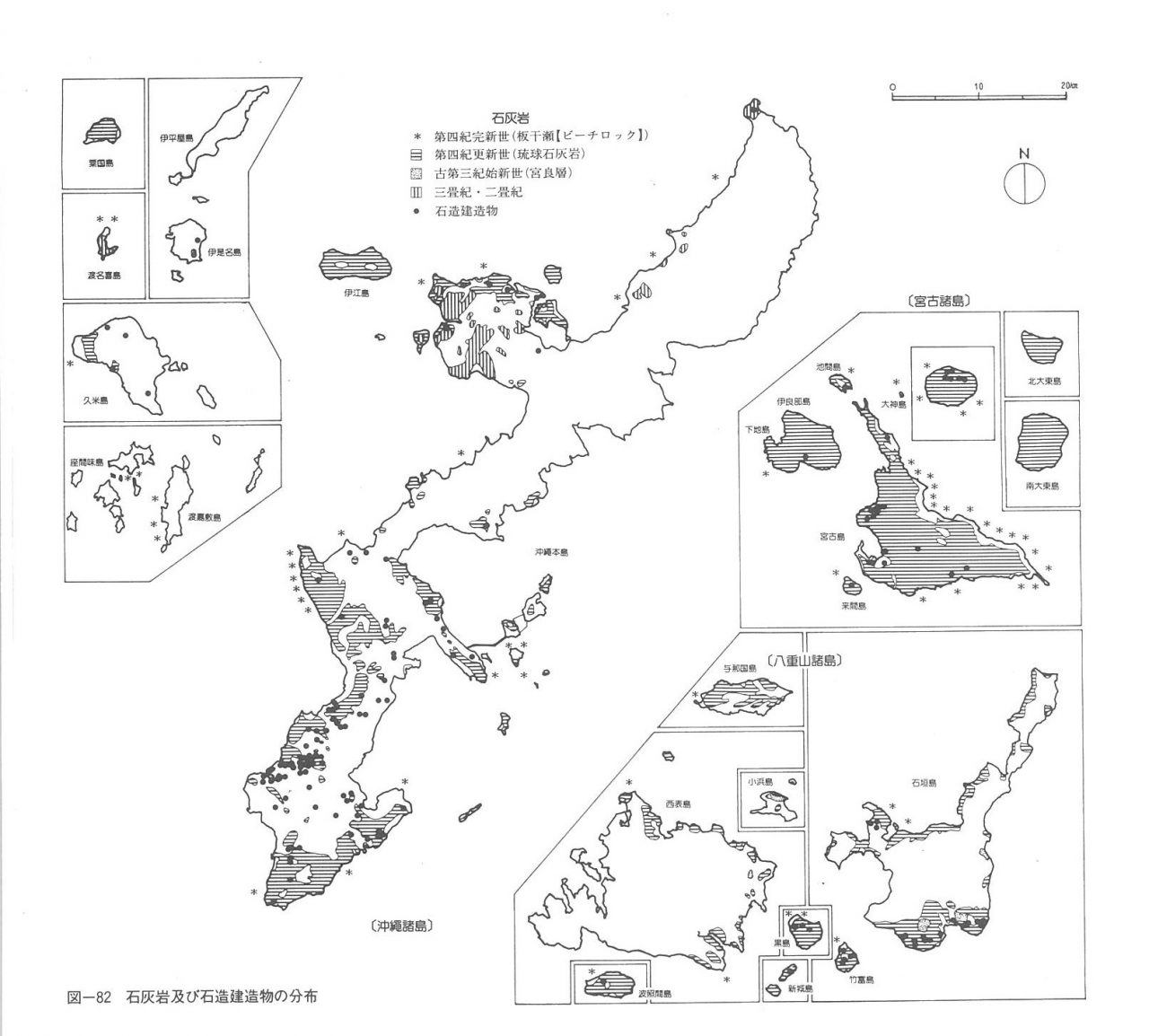

30% of the land of Okinawa consists of calcareous earth. The limestone produced there is called Ryukyu limestone. Strata were formed as coral reefs and dead habitant marine organisms accumulated on the seafloor. The strata surfaced due to tectonic deformation or lower sea levels, forming the current geology of Okinawa. The Ryukyu limestone has been a familiar material for the Okinawan people since ancient times. We would like to explore the chronology in Okinawa, focusing on lifestyles and Ryukyu limestone below.

-

Figure 3. Distribution of limestone and masonry buildings 3

Worshipped limestone – ancient times

In the ancient Ryukyu society, people found gods in everything from huge stones or trees to beaches and caves. Limestone was also worshipped. Spring water is often found near exposed limestone. In islets with limited accessibility to domestic water, sources of water and nearby limestone became the basis for people’s lives. The most representative example is Sefa Utaki. A triangular gap was formed by two huge rocks leaning against each other on top of a mountain with spring water. Even today, massive force is still applied to the contact point of the rocks. The huge rocks and gap – much larger than human scale – survived for thousands of years. People have been greatly awed by them and have regarded them as grounds for worship.

-

Figure 4. Looking back at the gap of Sangui

Processed limestone

Ryukyu limestone is porous and softer than other types of limestone, since it is mainly made of petrified coral reefs. Therefore processing technologies were easily developed. What is essential in life in Okinawa is countermeasures for the tropical climate (such as typhoons and heavy rainfall), and climate-induced damage, including termites. People began using Ryukyu limestone for building materials, since it is easily processible and has excellent drainage.

The limestone was fractured from the bedrock and large rocks in seashores and mountains, using iron tools, or hard rocks, and easily-handled size pieces were cut out. Stone materials were carried via water and land routes to become a foundation of castles/fortresses (e.g., Shuri Castle) and buildings for powerful figures.

-

Figure 5. Former stone quarry in Yomitan

Among all, the Nakamura House (designated as an important cultural property) in Kitanakagusuku Village in Nakagami District is a folk house, which was built with the best traditional architectural technology of Okinawa. The folk house uses Ryukyu limestone everywhere, such as the hinpun wall4 (made of Ryukyu limestone cut out and carried from the Yomitan stone quarry), stone walls, stone pavement, and a block for chopping firewood. Inside of the wind-blocking walls, everything is entirely paved with stones. In order to prevent termite damage, wooden posts were placed on floor post footings (made of limestone) that were higher than typical ones, and the building was jointed. Plaster used for the roof was made by baking coral, crushing it into fine pieces, and mixing it with straw. The roof tiles that were immobilized by plaster survived typhoons and blocked rain and wind. Limestone was used to block and protect buildings from natural threats.

-

Figure 6. The Nakamura House

Reconstructed limestone

After World War II, people acquired a technology to crush limestone into finer pieces. Mechanically-crushed fine limestone is a prime ingredient of concrete. The American army also turned their attention to Ryukyu limestone, and introduced a concrete production technology to build facilities. Concrete buildings replaced traditional wooden buildings that suffered from typhoons and termites, since the raw materials were readily available and concrete was suitable for the tropical climate. Concrete was also used for infrastructure development, including highways and monorails, in addition to buildings. Standardized concrete blocks were loaded on trucks and fluid cement concrete in concrete mixer trucks, and concrete structures spread throughout Okinawa. Today, 90% of buildings in Okinawa are made of concrete. Urbanization of Okinawa was brought about by popularization of concrete, and was actually largely attributed to Ryukyu limestone.

-

Figure 7. Current Okinawa city

Foundation of Ryukyu Limestone

The huge Ryukyu limestone was worshipped as a god in the past, and primitive “ma” (in-between) was born due to its nature. Ryukyu limestone was later processed by human hands, establishing a base to support the royal residence and wooden dwellings for powerful figures. Later, Ryukyu limestone was crushed into small particles by heavy machinery, and transformed into the current city of Okinawa. However, when taking a broad view, the fact that the land of Okinawa is covered with Ryukyu limestone has never changed since ancient times to the present day. People continue making buildings on the limestone land, while updating technologies and construction methods. Limestone derived from coral has always been a foundation of the “hashirama equipment”, which has been developed in architecture and the city of Okinawa.

Notes:

1. Described in ” Studies on Divine & Human Environment in Ryukyuan Rituals” (Tsutomu Iyori, Chuo Koron Bijutsu Shuppan, 2005) on p.429

2. The current yohaijo for Kudaka Island is in Sangui, but was originally located at a different place in Sefa Utaki. There is no historical evidence of worshipping Kudaka Island from Sangui, and therefore the yohaijo in Sangui is believed to have been built in later years. According to architectural historian Tsutomu Iyori (1949- ), “Oaraori” had been performed on Kudaka Island, and its venue was later moved to Sefa Utaki in the course of simplification of the ritual. Therefore, a visionary journey to Kudaka Island and Niraikanai is incorporated into the rituals in Sefa Utaki, which have been handed down until today.

3. From “Masonry Culture of Okinawa” (Shunsuke Fukushima, Shinpo Publishing, 1987), Figure 82. Distribution of limestone and masonry buildings on p.182

4. A short wall between a gate and main building of folk dwellings in Ryukyu. It is also believed to be a charm against evil spirits.

Reference materials:

Tsutomu Iyori “Studies on Divine & Human Environment in Ryukyuan Rituals” (Chuo Koron Bijutsu Shuppan, 2005)

Taro Okamoto “Forgotten Japan―Treatise on Okinawan Culture” (Chuokoron-Shinsha, 2002)

Chinen Village Board of Education “Sefa Utaki Development Project Report (Excavation survey, material version)”

Yashu Nakamatsu “Gods and Villages: Villages in Okinawa” (Institute for Okinawan Studies, University of the Ryukyus, 1968)

Nanjo City Board of Education “Report of Development Implementation Plan for the Periphery of Sefa Utaki” (Nanjo City Board of Education, 2013)

Shunsuke Fukushima, “Culture of stoneworks in Okinawa” (OkinawaShuppan, 1987).

Figures:

1. Created by Nakatani laboratory

2. Figure 10 from Chinen Village Board of Education “Sefa Utaki Development Project Report (Excavation survey, material version)”, edited by Nakatani laboratory

3. From “Culture of stoneworks in Okinawa” (Shunsuke Fukushima, Okinawa Publishing, 1987), Figure 82. Distribution of limestone and masonry buildings on p.182

4. Taken by Nakatani laboratory

5. Taken by Nakatani laboratory

6. Taken by Nakatani laboratory

7. Taken by Nakatani laboratory

Norihito Nakatani

An architectural historian, professor of Waseda University, and the principal researcher of this study. His chief literary works include Shifting Land, Shape of Living –Navigating the Boundaries of Plates (Iwanami Publishing, 2017), Revisiting Kon Wajiro’s ʻJapanese Houses’ (as part of the Rekiseikai group, Heibonsha, 2012), Severalness+: The Cycle of Things and Human Beings (Kajima Institute Publishing Co.,Ltd., 2011), and The Study of Classical Literature, the Meiji Period, and Architects (Ikki Shuppan, 1993).