Series Shoei Yoh: A Journey of Light

Architecture in Motion

19 Mar 2025

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Columns

- Essays

- Japan

Architect YU Momoeda, who is a long-time admirer of Shoei Yoh, participated in the Find and Tell residency program of the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), providing his readings of the archival materials that Yoh donated to the Centre’s collection. Here, he shares his thoughts on Yoh’s architecture and words with a focus on the keyword “motion”.

Buildings are generally regarded as immobile. Hence, when finishing an interior wall, for example, it is common practice to layer a pair of gypsum boards and apply filler along the joints to create a blank, seamless surface. Despite the fact that such finishes often end up cracking due to the building’s movements, many architects are drawn to abstract walls devoid of visible joints. But Shoei Yoh thought differently—he understood buildings as things that move.

Yoh devised a way to create a building in which light occupies the place of the joints that absorb movement between rigid materials. He designed a UFO-like house imbued with a sense of weightlessness and a crustacean-like gymnasium that appears poised to spring into motion at any moment. He sought to shape structures that respond to natural phenomena through their forms. He envisioned architecture as something that synthesizes the materials and technologies unique to its time; as something unbound to the earth, like an automobile or airplane; and as something dynamically attuned to the laws of nature, like a sunflower turning to face the sun.

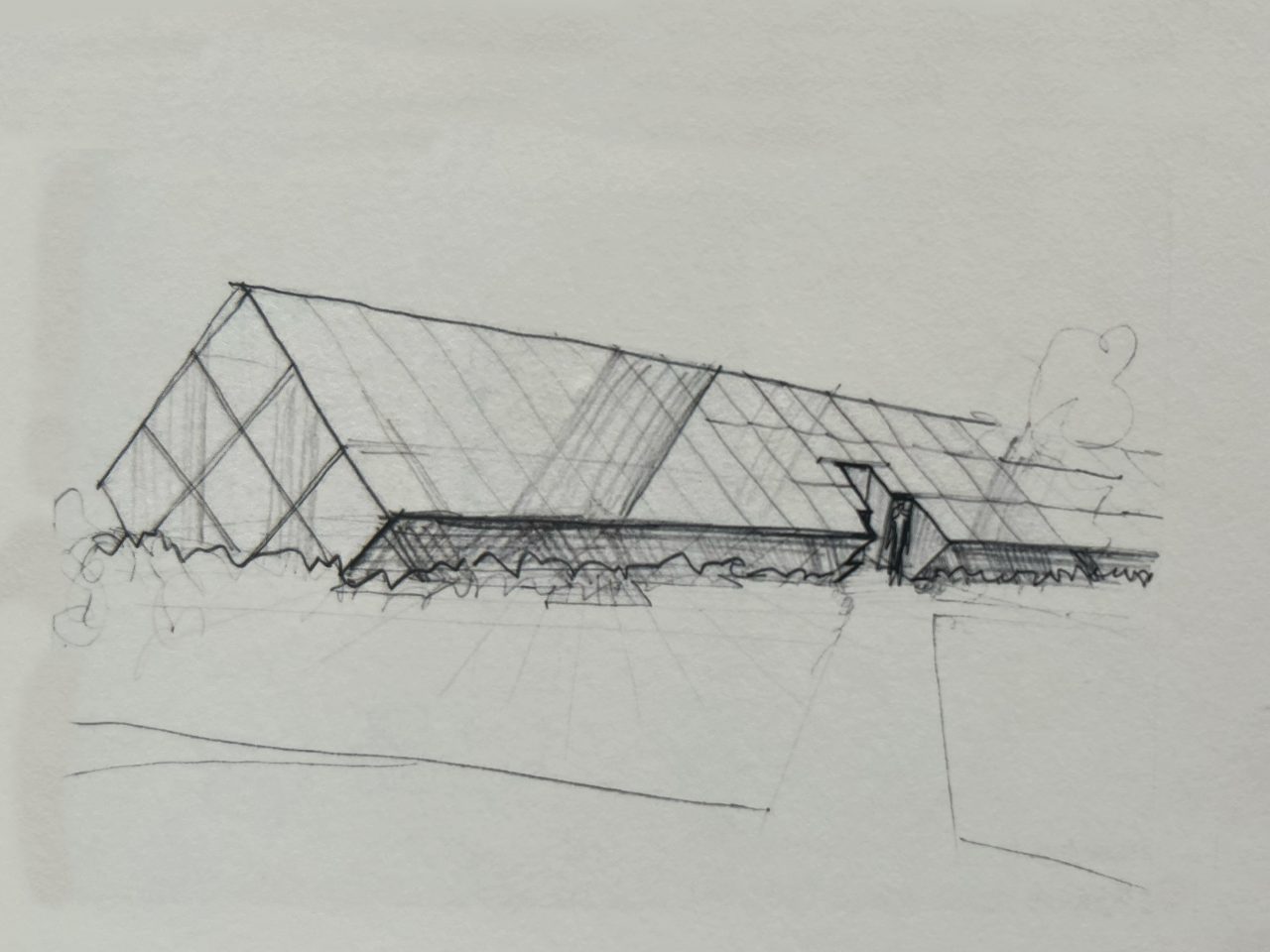

Joints of Moving Light: The Stainless Steel House with Light Lattice

Yoh, who began his career in interior and product design, developed his interest in natural phenomena through designing the Ingot Coffee Shop. Where architecture fundamentally differs from interior design is in its direct engagement with the ever-changing external environment. Unlike artificial light, natural light exists in constant flux, continually marking the passage of time. The Stainless Steel House with Light Lattice was conceived as a building that incorporates such motions of nature.

Prior to this project, Yoh believed that a floor and a roof were all that was fundamentally necessary to make a house. He reasoned that because a family is something whose composition changes as children grow, a house must be a space that responds to and accommodates such changes. However, because his clients for the Stainless Steel House with Light Lattice were a childless couple, he shifted the focus of his design from the changes within the family to the changes in sunlight. This, combined with his decision to incorporate the site’s irregular topography into the interior, gave rise to a richly articulated space where the moving light and shifting topography play off the visual uniformity of the house’s gridded framework.

“Interfaces between people, technology, and nature must incorporate gel-like buffer zones or interstitial gaps (air can act like a spring).” Shoei Yoh, “Shoei Yoh: 12 Calisthenics for Architecture”, SD 9701, no. 388 (1997): 142.

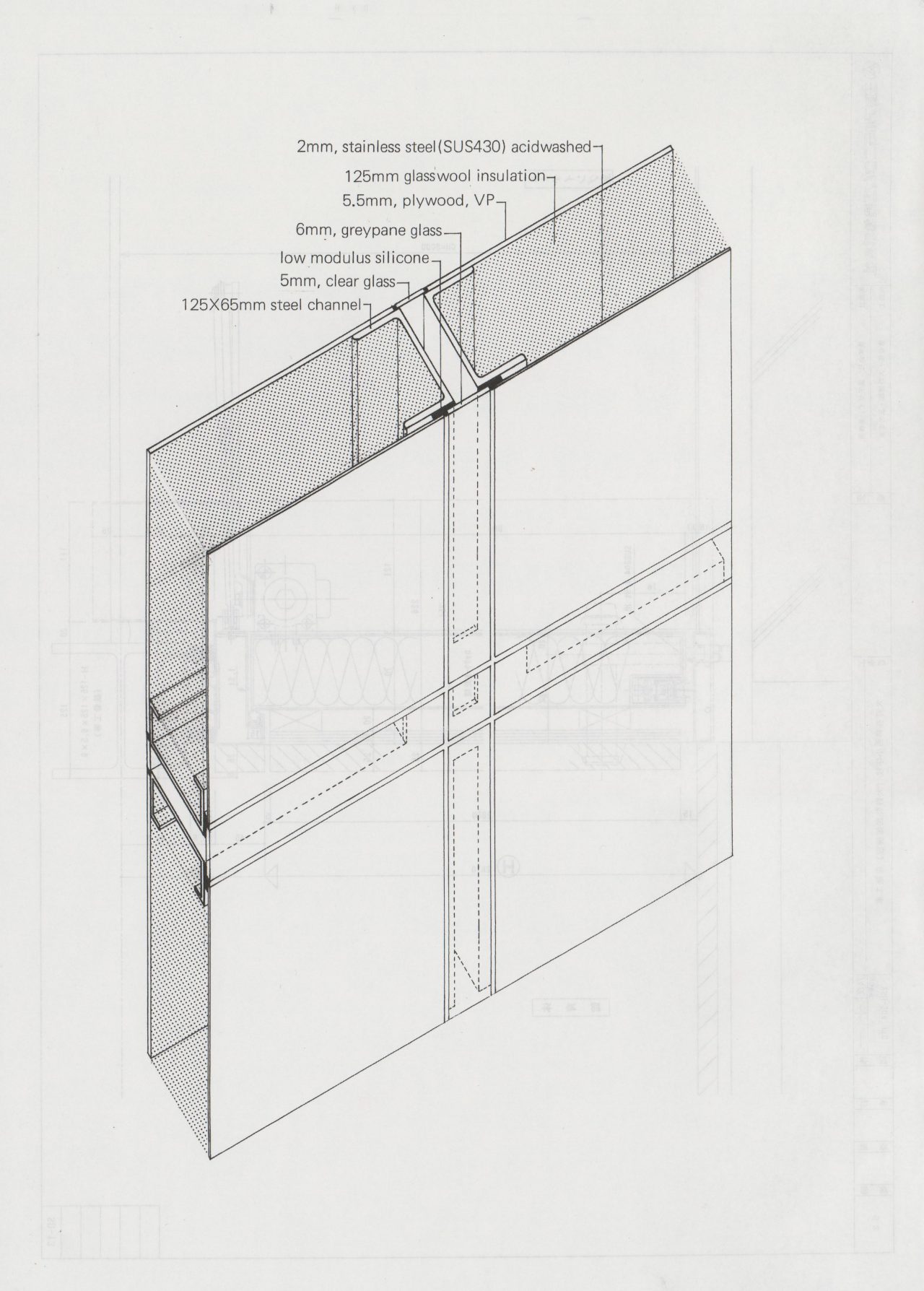

The Stainless Steel House with Light Lattice is literally built of stainless steel: its walls consist of stainless-steel panels, spaced apart with gaps to allow the passage of light. Yoh, having developed expertise in handling glass through previous projects, was mindful of the detailing of rigid materials and their movement-absorbing joints. For this house, he joined the stainless-steel panels, doubled-up steel channels, and infill glass using silicone, creating a flat, abstract space composed of minimal elements. He thus resolved the movement between the disparate materials through an approach that was both phenomenological and tectonic.

-

Stainless Steel House with Light Lattice, wall detail. Shoei Yoh Archive, Kyushu University.

Freed “Non-Architecture”: The Kinoshita Clinic

In his pursuit of so-called “non-architecture”, Yoh sought inspiration in the details of industrial products, such as automobiles and airplanes. What project better embodies this technological perspective, along with his desire to free architecture by cutting its ties to the earth, than the distinctly UFO-like Kinoshita Clinic?

“Basically, in the world of my dreams, buildings just move as a matter of course. . . . But, you see, it’s written right at the beginning of the Building Standards Law that ‘a building is something fixed to the ground’. My work stems from my rejection of this definition.” Shoei Yoh, in a conversation with Hiroyuki Suzuki, “Tekunorojii to kosumorojii no aida” [Between technology and cosmology], Kenchiku Bunka 42, no. 491 (September 1987): 136–137.

In a conversation with architectural historian Hiroyuki Suzuki, Yoh speaks about his fantasy of the Ingot Coffee Shop transforming into different sizes, taking on various functions, and moving (teleporting) to other locations. He acknowledges that Archigram and Superstudio were major influences, with their visions of architecture untethered from the earth. He recognized both portable installations, like Archigram’s Instant City, and enormous constructions spanning the globe, like Superstudio’s megastructures, as works of environmental design. This perspective very much defined his career, which yielded a wide range of designs, from luminaires to open-air concert venues.

Yoh was also interested in new technologies, particularly those developed by NASA. In the world of automobile and aeronautic engineering, the idea of a “flying car” was first dreamt up in the early 1900s. Today, the notion of what a car can be is being further redefined with advancements in drone technology, which is inspiring concepts for new kinds of vehicles capable of flying freely through the skies. Considering that space stations, which enable humans to inhabit space for extended periods, have already been tried and tested in the realm of aerospace engineering, the day may soon come when “flying buildings” become a reality, whether on Earth or elsewhere. Yoh’s visions of “non-architecture”, which leaned heavily on scientific technology, represented his attempts to free architecture from its existing constraints by rethinking it from scratch.

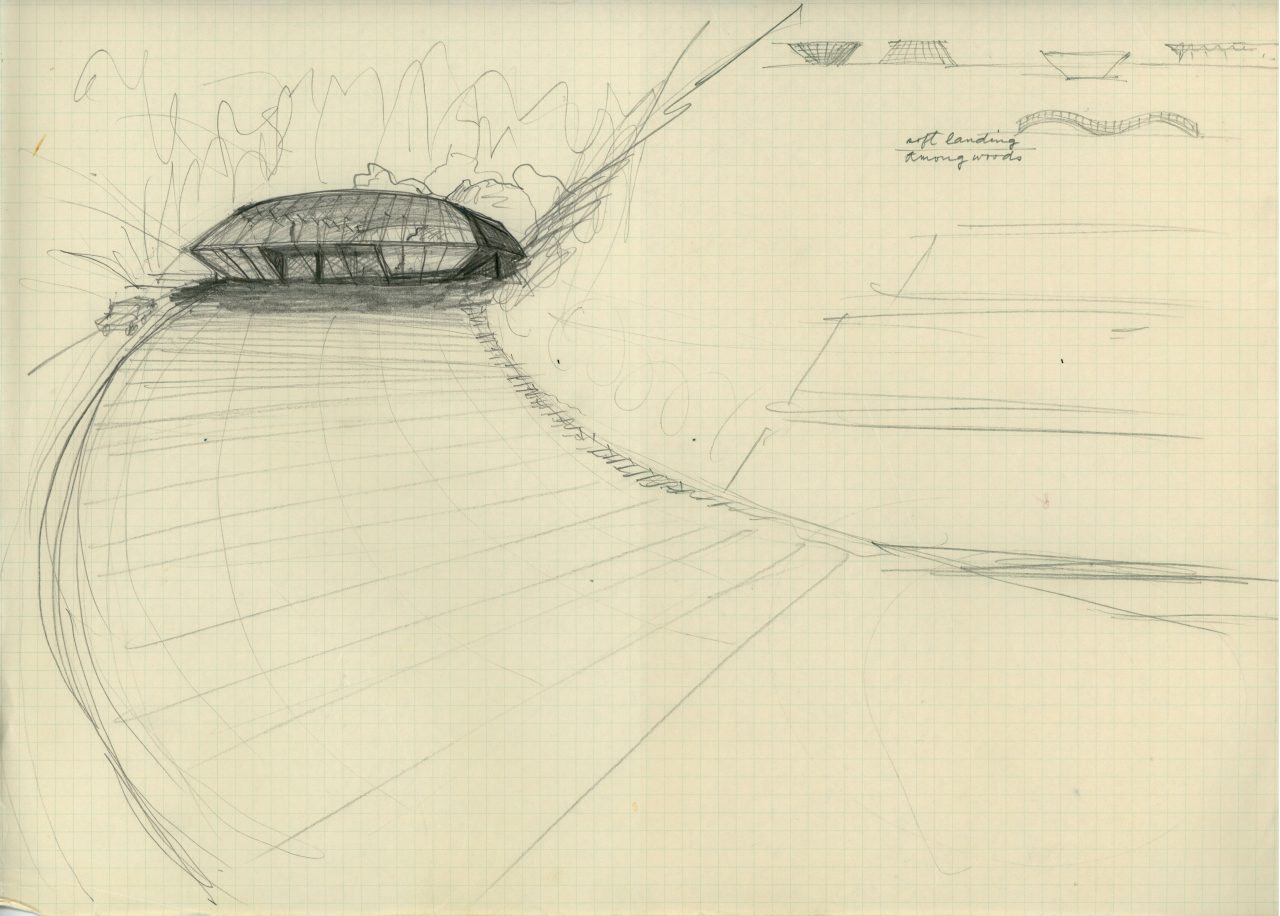

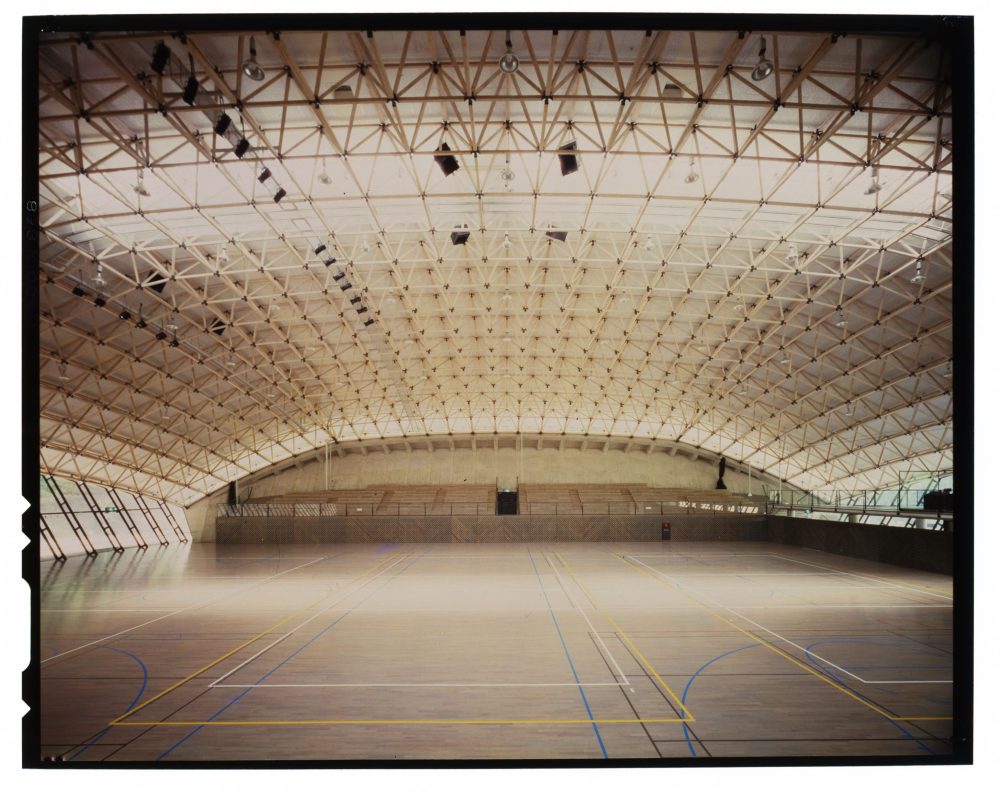

Crustacean in the Landscape: The Oguni Dome

The Oguni Dome is Japan’s first large-scale wooden building exceeding 3,000 square meters. It was an unprecedented project that ventured into uncharted territory for timber architecture while tackling numerous challenges, including the utilization of small-diameter heartwood (thinned timber), revitalizing the local community, introducing a lattice-truss construction method that joins timber with spherical metal nodes, and securing ministerial approval. The level of completeness achieved by this work is quite astonishing; beyond realizing a novel timber structural system, it maximizes the potential of materials by employing them where they are most effective, such as the glass skylights that enhance the gymnasium’s functionality and reduce operational costs, the glass curtain walls tilted downward to avoid direct sunlight, and the concrete anchor blocks with integrated seating.

Architectural feats aside, it is also very intriguing how Yoh symbolically related the children of Oguni to the building by having each of their names inscribed onto pieces of the thinned timber in the roof structure, such that the individually delicate elements form a communal core in the aggregate. In addition to helping to foster an affectionate bond with their hometown, this gesture ensured that the building would continue to live on within the children’s memories, even should they one day leave Oguni.

“This gymnasium gives the impression that it might slide out of the depression in the deep mountainous landscape where it is nestled. This effect is due to the fact that all points of contact between its form and the ground are intentionally designed in a minimal manner.” Shoei Yoh, “Ambient Design Matrix”, Kenchiku Bunka 42, no. 491 (September 1987): 80.

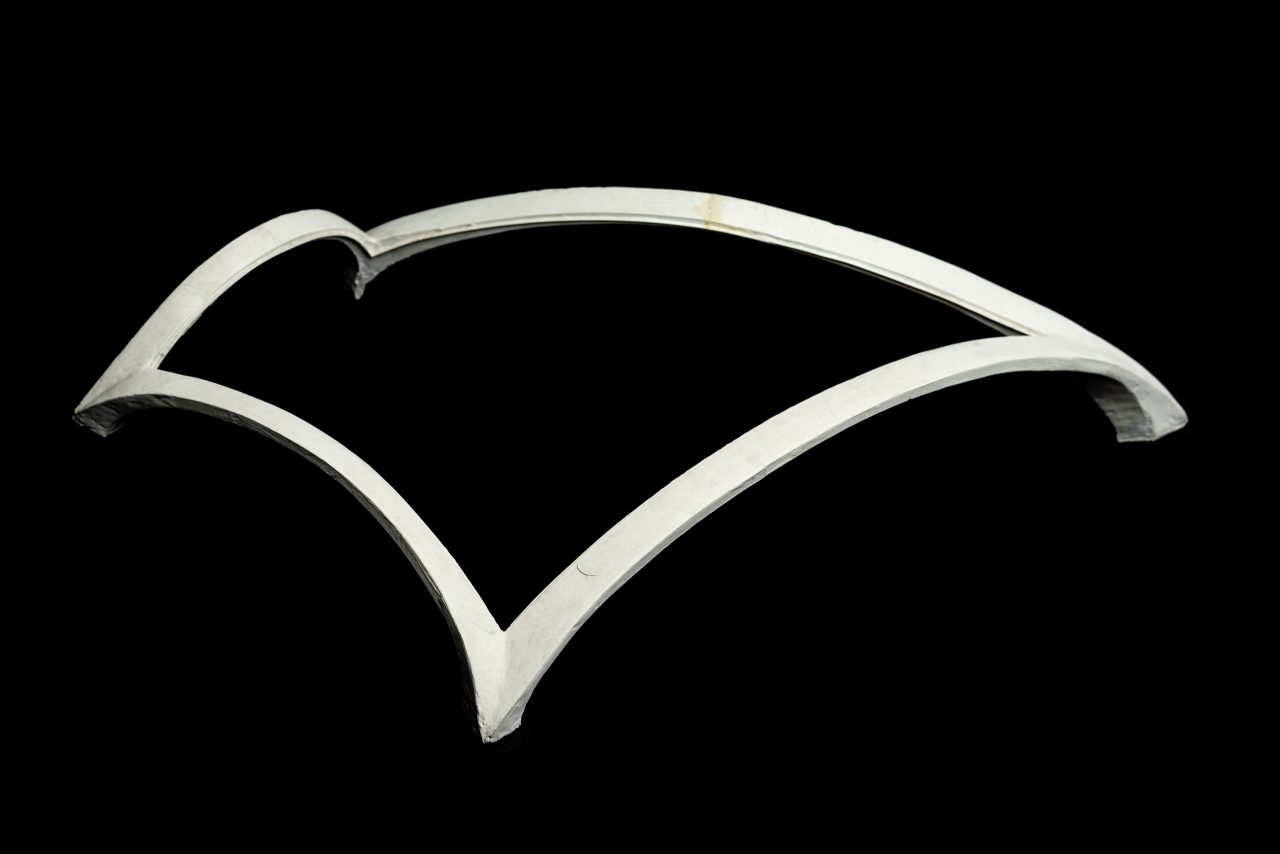

The Oguni Dome picked up on the idea of a transformable, movable building from the Ingot. As Yoh shifted into the computational design phase of his career following this project, one could say that it marked a notable turning point in how “arbitrariness” is manifested in his work. For the Oguni Dome, which he referred to as a “crustacean”, he employed a univariate design approach, setting arbitrary rise values and having the structural engineer run calculations to define the arched forms. In subsequent projects, however, he leveraged computational tools that enabled him to search for optimal forms by setting multiple parameters, generating more fluid, organic designs. The “crustacean” resting in Oguni’s landscape would go on to evolve into a “galaxy” and a “drifting cloud” as a result of this shift.

From a “Galaxy” to “Drifting Cloud”: The Toyama Galaxy Hall and Odawara Municipal Sports Complex

“[I]t requires considerable effort to create three-dimensional curved surfaces, unless they occur as natural phenomena.” Shoei Yoh, in an interview with Masaaki Iwamoto, Akihiro Mizutani, and Toshiaki Sato, “Mokuzō to konpyutēshon ga deatta toki” [When timber construction and computation meet], Shoei Yoh Archives Report (March 2020): 63.

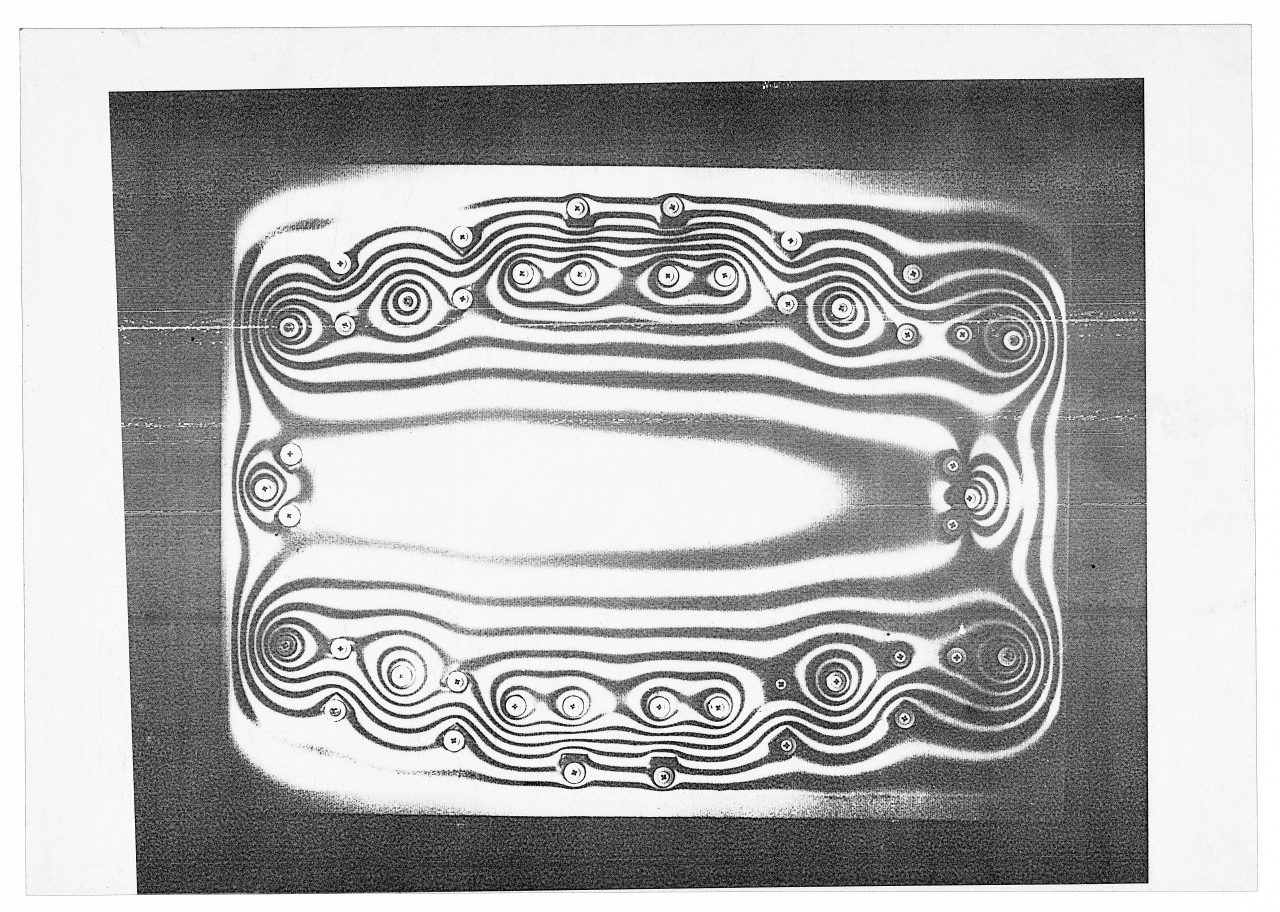

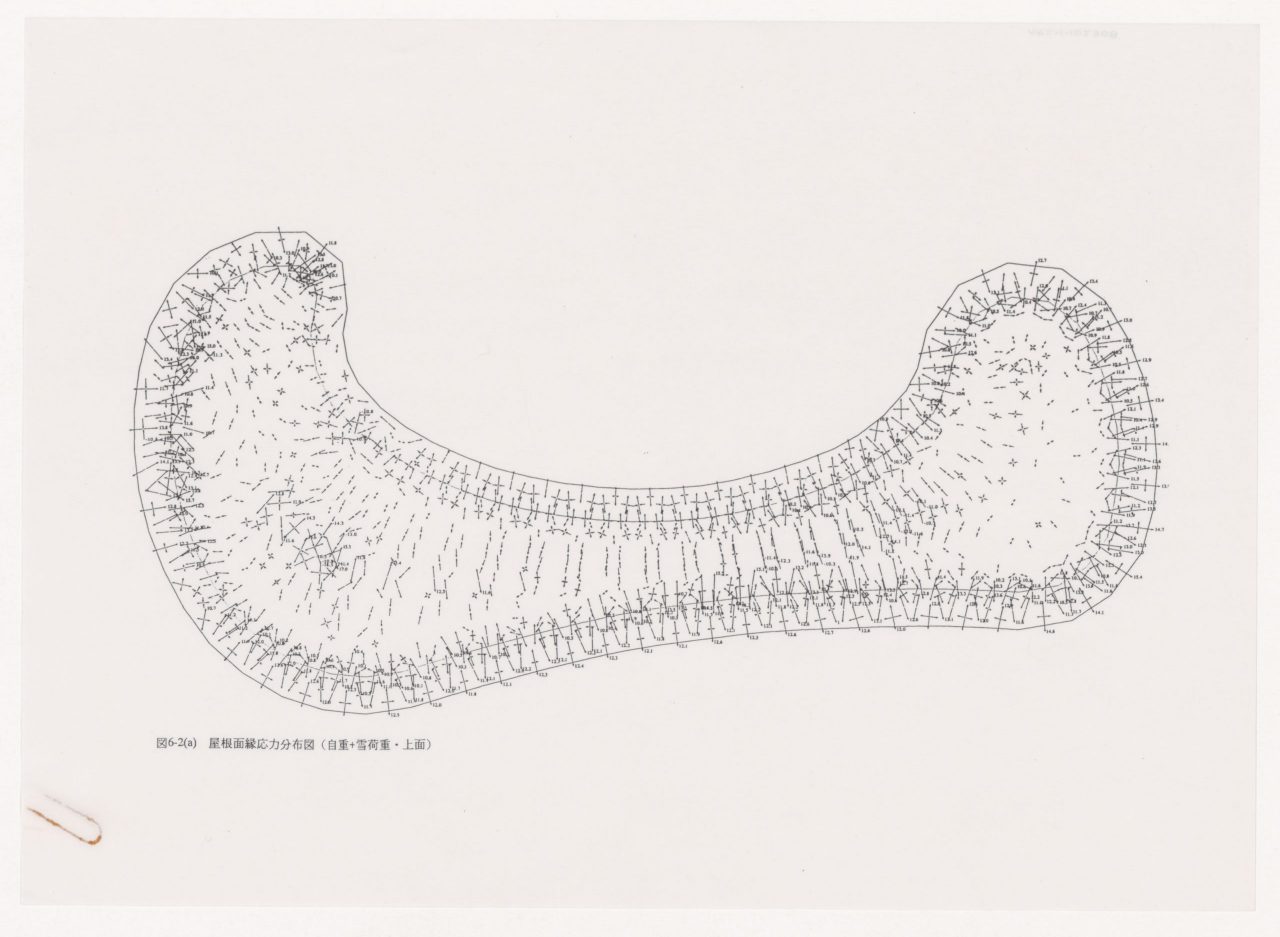

After completing the Oguni Dome, Yoh began attempting to create buildings featuring three-dimensional curved surfaces, inspired by Arata Isozaki’s competition proposal for the Palau Sant Jordi indoor arena in Montjuïc, Barcelona. The Galaxy Toyama was the first of these projects. Photoelasticity experiments, which use light to visualize stress distribution on complex curved surfaces, played a major role in its design. The key was that this method, which structural engineer Gengo Matsui had been researching at the time, allowed the stress patterns to be verified using a physical mesh model. While computer analysis provided numerical descriptions of how the roof would deform under its own weight and snow loads, the physical model enabled Yoh to grasp these effects through the medium he most trusted: light (and shadows).

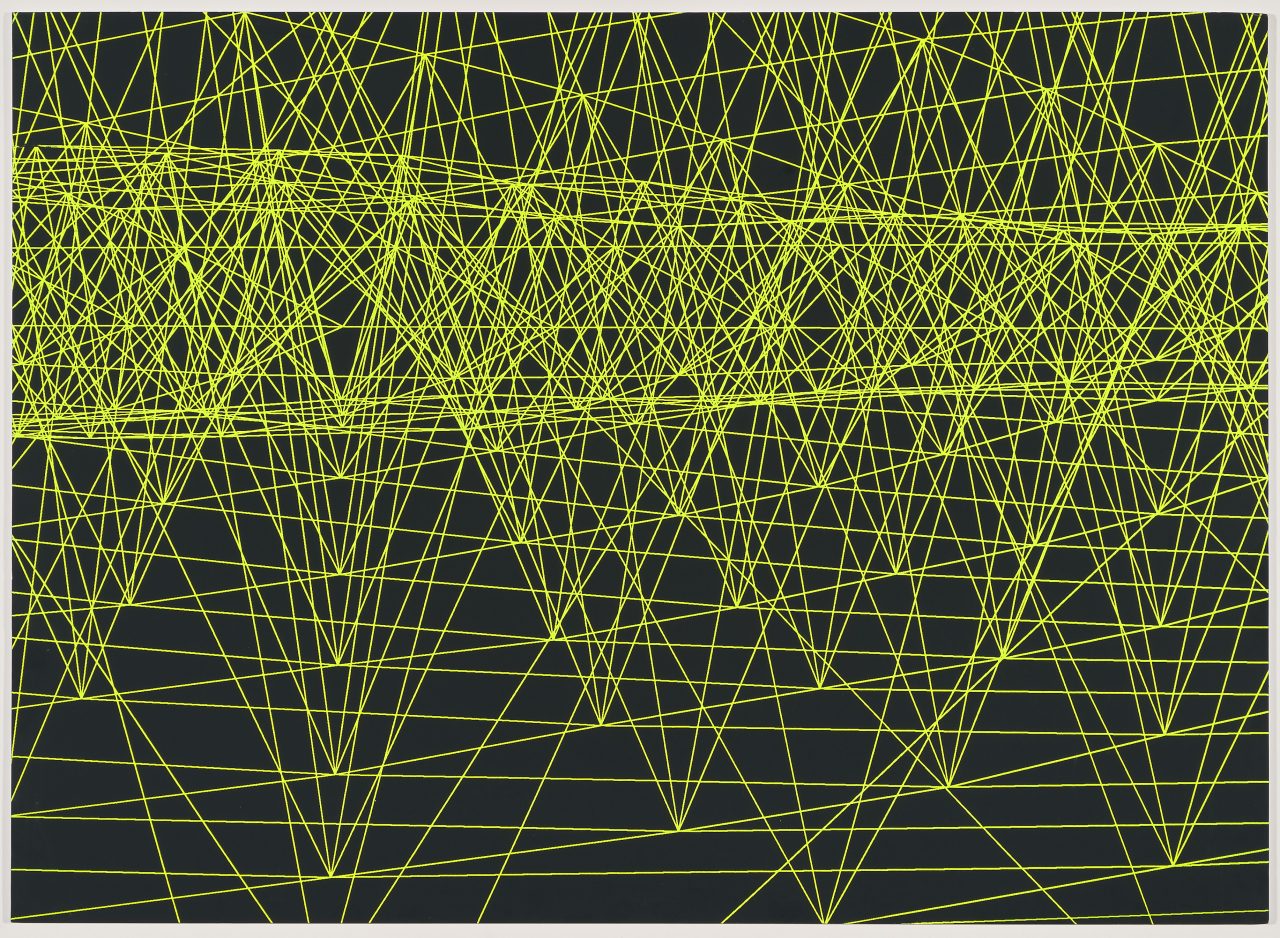

Computer simulations felt “like magic” to Yoh, who was interested in finding optimal architectural solutions through a dialogue with natural phenomena, such as gravity. Computational tools allowed him to shape the Galaxy Toyama’s three-dimensional curved roof in direct response to snow loads using steel trusses, which generated a complex geometric interior space that he referred to as a “galaxy”. Computer-controlled fabrication technology also made it possible to construct the roof economically, despite the fact that all its components were uniquely dimensioned.

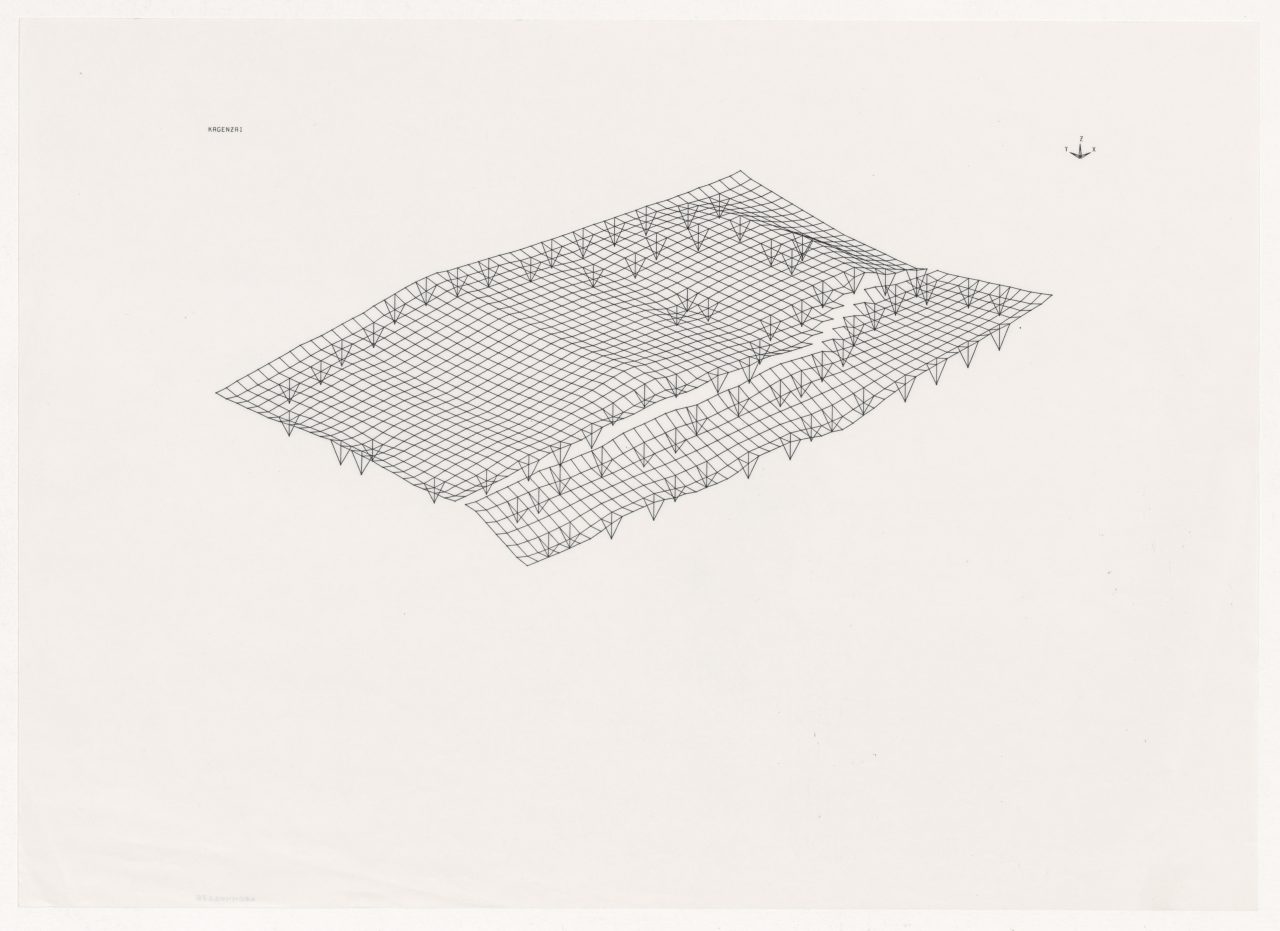

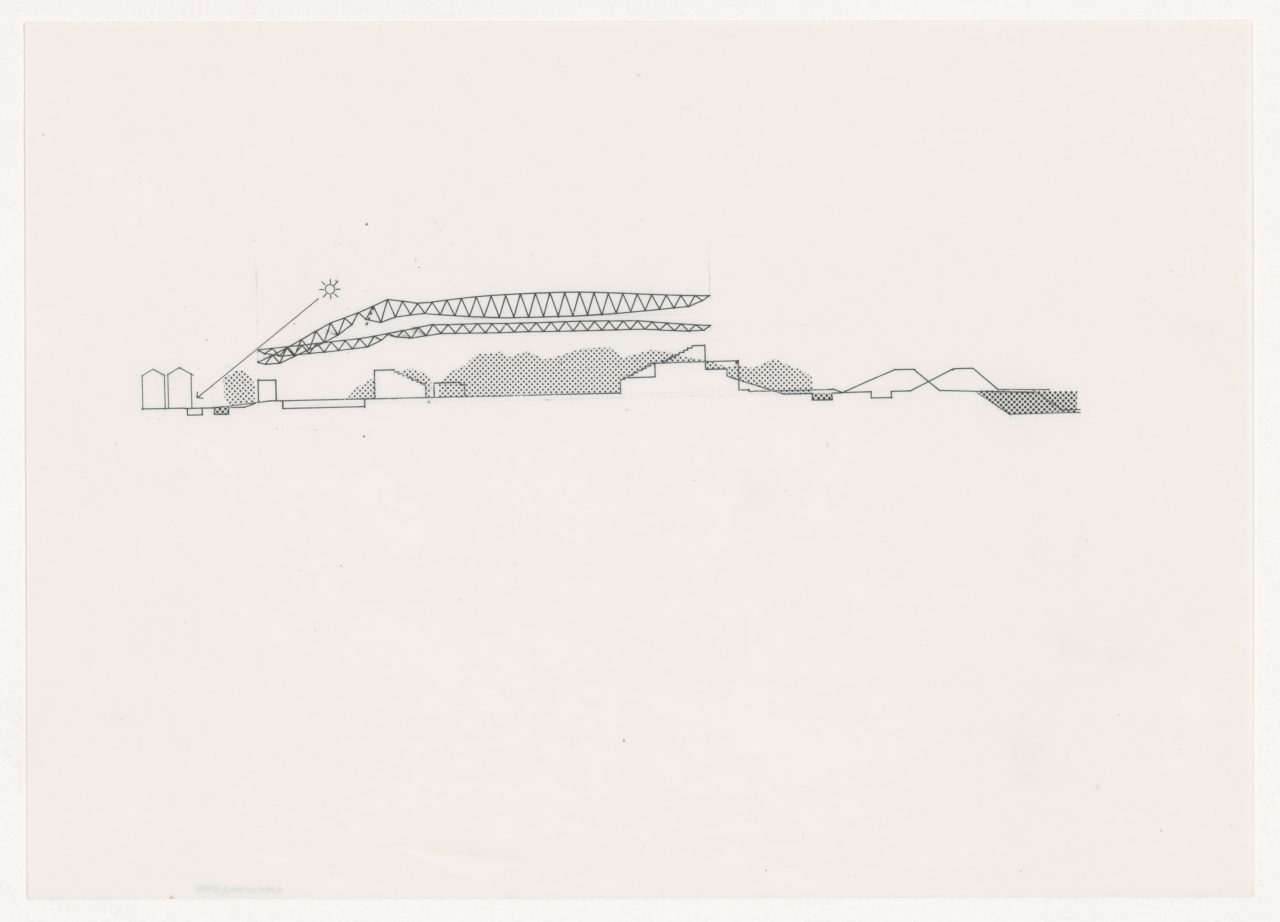

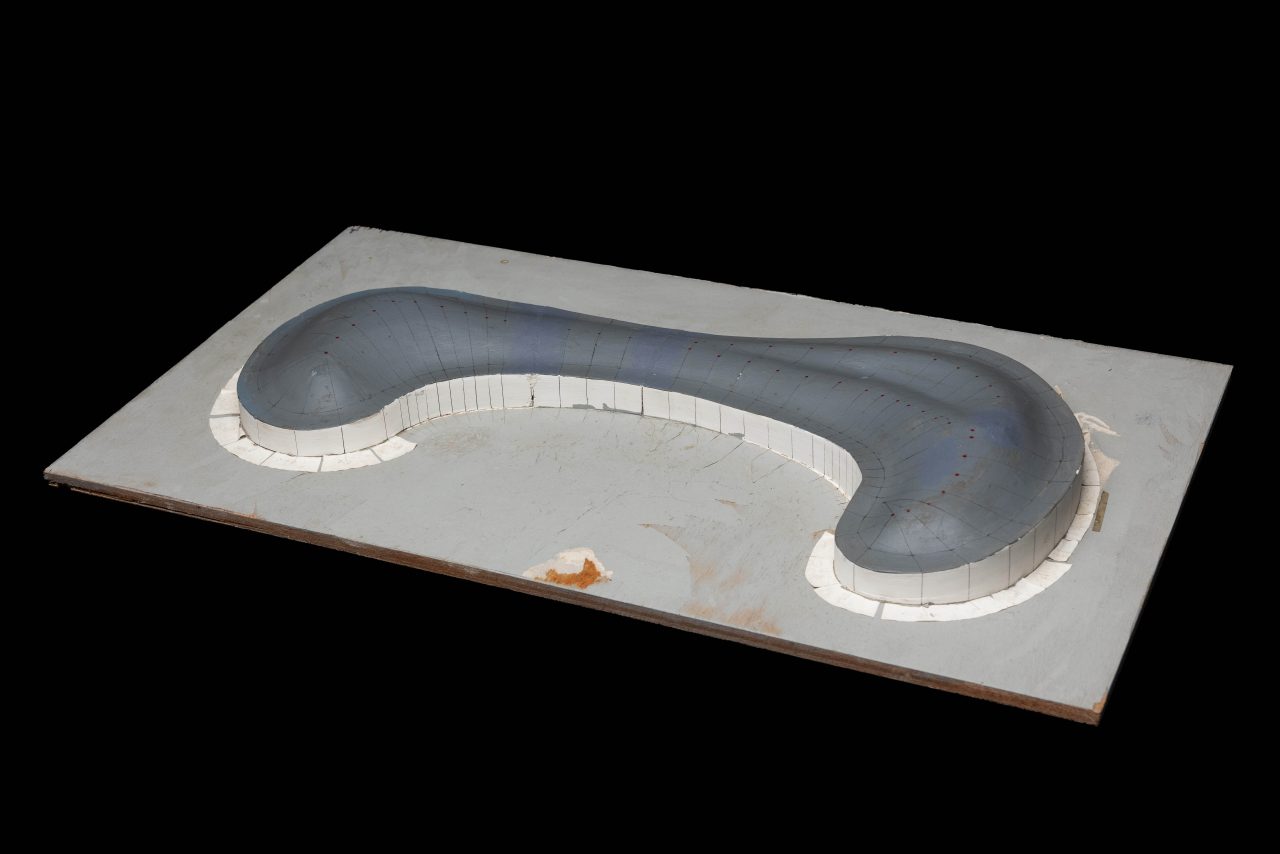

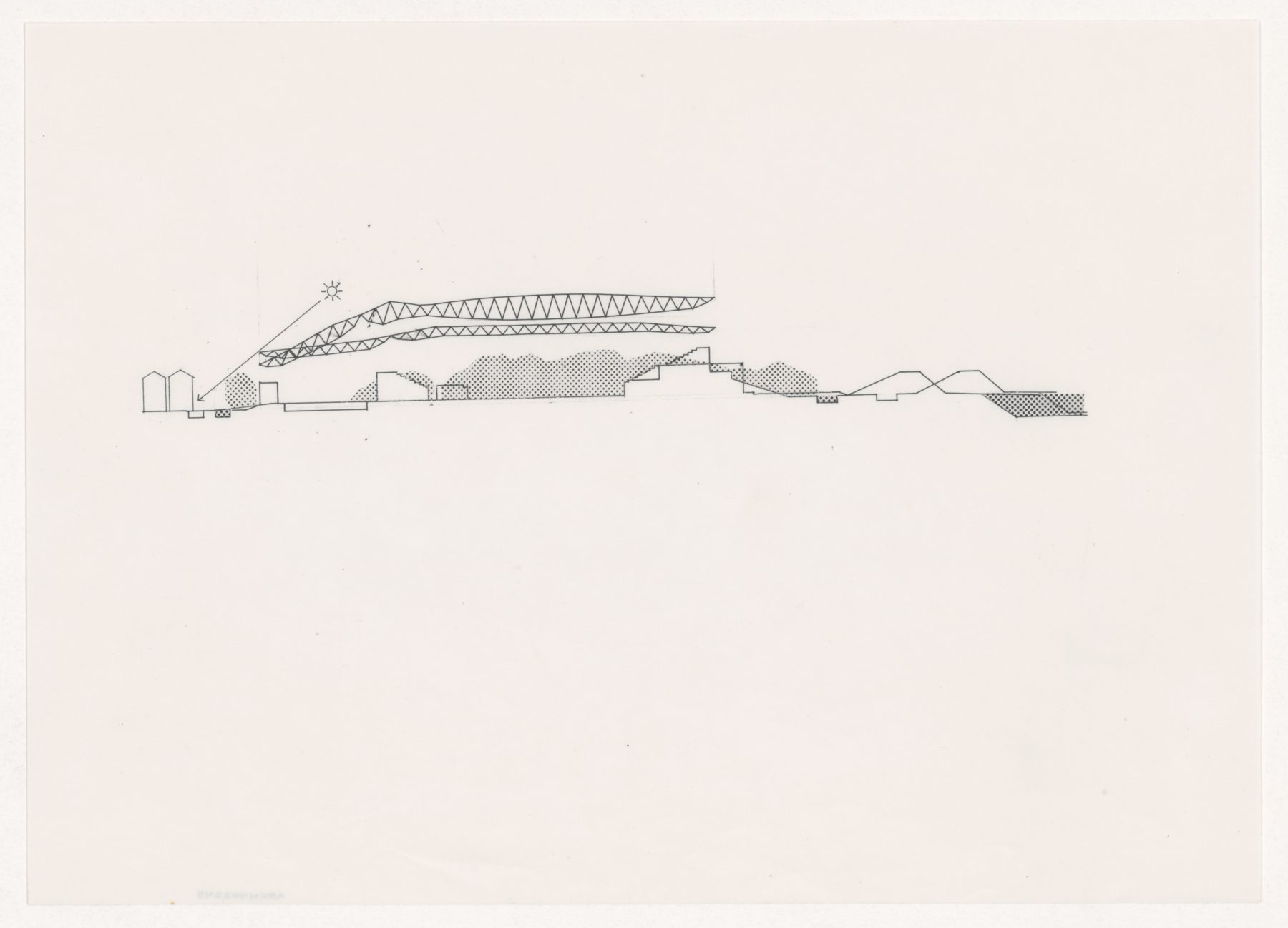

While the Galaxy Toyama was under construction, Yoh worked on the Odawara Municipal Sports Complex, a competition proposal featuring a distinctive large roof he called a “drifting cloud”. Unlike the Galaxy Toyama’s roof, which levels out along the edges, the proposed roof was envisioned as an “asymmetrical continually changing” design optimally attuned to the sun’s position, wind flow, and the surrounding environment. By using a computer to simultaneously analyze various parameters, such as the necessary heights of each space and the placement of columns, the building evolved into a work of “topological architecture” that embodies the idea of continual change.

The Behavior of Materials: The Glass Station, Naiju Community Center and Nursery School, and Uchino Community Center for Seniors and Children

After realizing a steel-frame structure shaped in response to snow loads with the Galaxy Toyama, Yoh continued engaging in dialogues with natural phenomena using different materials, such as glass, concrete, and bamboo.

In explaining the Glass Station and Naiju Community Center and Nursery School, Yoh draws a contrast between the two structures by employing the dichotomy of “draping versus pulling taut”. The Glass Station forms a minimal surface made with a uniformly stressed glass membrane, which was designed using computational tools and wind tunnel testing. The glass membrane, stretched across the inner side of the perimeter concrete frame, maintains its shape by being evenly tensioned, much like the strings of a tennis racket. In contrast, the Naiju Community Center and Nursery School forms a shell structure made with concrete cast over a bamboo mesh framework, which was woven by members of the local community. Yoh notes how the features that may seem extraneous, such as the loose folds and fluttering edges, help imbue the building with presence and also contribute to its appeal to children as a place to play. Thus, while the Glass Station expresses a trim, streamlined aesthetic achieved through tension, the Naiju Community Center and Nursery School took shape as a relaxed, embracing environment achieved through compression.

For the Uchino Community Center for Seniors and Children, Yoh employed a parametric approach in which the rise of the distinctive undulating concrete dome roof changes in accordance with the spacing of the columns. This enabled the creation of a cohesive design that is rational both structurally and economically. Departing from the square plan of the Naiju Community Center and Nursery School, the roof is irregularly shaped in plan and relies on its eaves to bind the entire structure together along its periphery.

“It’s a gate to the [forestry] town of Oguni, after all. . . . I felt that I had to create something that would be impossible to do in wood, or else it would be an affront to wood.” Shoei Yoh, in an interview with Naoki Ezoe, Shoei Yoh: 1970–2000 (Kataribe Bunko, 2000), 69.

This quote was made in reference to the Glass Station. Yoh was acutely mindful of the proper application of materials, and this was what enabled his buildings to take on forms that evoke living organisms, even as he used computational analysis to achieve a multifaceted rationality in structure, construction, and cost. Applying the form-finding method of Frei Otto, one of his influences, he aimed to develop architectural forms by translating the materials’ intrinsic “behaviors”—a term that, in Japanese (furumai), originally described the way a bird moves its wings freely as it dances lightly through the air. Indeed, these buildings, which leverage the physical properties of glass, bamboo, and concrete, elevating them into their structure and construction, evoke a sense of light, organic movement.

Buildings as Transient Organisms

In the aforementioned conversation, Yoh shares his view on the life of buildings. He speaks of them as things that are neither eternal nor universal, capable of living on only through continual renewal. He adds that, just as with humans, the most important thing is that buildings are able to exist happily over the course of their lifespan, and this is why he is interested in equipping them with the ability to adapt to change. His perspective aligns with the tradition of shikinen sengū [periodic shrine relocation] practiced at the Ise Grand Shrine.

“We keep ourselves upright by swaying, lunging, clinging to hanging straps, and shifting our weight into our legs. Trees and grasses do the same, and buildings are no different.” Shoei Yoh, “Shoei Yoh: 12 Calisthenics for Architecture”, SD 9701, no. 388 (1997): 15.

Yoh viewed buildings in the same way as humans, plants, and other lifeforms; that is, as transient things existing within nature’s fluctuations, synced to the motion of our rotating planet. He engaged with both humans and architecture earnestly and with an understanding of the laws of nature. He saw buildings as things that change with nature and can be dismantled at any time. He sought to redirect society toward a future where materials are sourced locally and recirculated within communities. He reimagined buildings as transformable, portable, and light-treading, leaving a minimal impact on the earth. Are these ideas not still innovative even today, in a time when environmental consciousness has become the expected norm? Shoei Yoh conceived architecture from within the motions of light and various other phenomena.

Top image: Odawara Municipal Sports Complex. Canadian Centre for Architecture (Shoei Yoh Fonds, ARCH402245, gift of Shoei Yoh). © Shoei Yohx

YU Momoeda

Born 1983 in Nagasaki, Japan. Principal of YU Momoeda Architects. Project Associate Professor at the Built Environment Center with Art & Technology (BeCAT) of Kyushu University. Class-I licensed architect in Japan. Graduated from the Environmental Design Course of Kyushu University’s School of Design in 2006. Earned a master’s degree from the Yokohama Graduate School of Architecture (Y-GSA) in 2009. Worked at Kengo Kuma & Associates before founding his practice in 2014. Participated in the Find and Tell residency program of the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) in 2019 and penned an essay on Shoei Yoh’s work. Architectural works include the Agri Chapel, Four Funeral Houses, Farewell Platform, and CYCL. Awards and honors include the AR Emerging Architecture Awards Shortlist (2017) and Highly Commended (2018), DFA Design for Asia Awards Grand Award (2017, 2021, and 2024), AIJ Selected Architectural Designs Young Architects Award (2018), and AACA Yoshinobu Ashihara Award (2021).