Series Shoei Yoh: A Journey of Light

Shoei Yoh: Architecture of Light, the Real, and Monism

20 Dec 2024

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Columns

- Essays

- Japan

Architectural historian Yoshitake Doi, who began teaching in Kyushu in the 1990s and witnessed firsthand as Fukuoka-based Shoei Yoh completed numerous works one after another, explores the essence of Yoh’s architecture.

In an Age Called Postmodern

There was a time when postmodernism played with fiction. It constructed fictions and then exposed them. Architecture, fundamentally, is about constructing certain ideals. Works of architecture are founded upon invented systems, ideals, dreams, ideologies—things that do not exist in the so-called state of nature. For this reason, they are conceived as fictions of sorts, for better or for worse.

Back during that time in the 1990s, Shoei Yoh said to me that it had come to the point where the only remaining possibility was to build “non-architecture”. He appeared as a maverick to my eyes for still holding faith in the real rather than fiction.

Dichotomy, Sectioning, and Geometry

Buildings are generally understood as dialogues between elements that support and those that are supported. This dichotomy has persisted throughout the ages, manifesting in the post-and-lintel structures of ancient temples, the vault-and-rib relationship in Gothic buildings, and the Renaissance debate over whether the essence of architecture lies in the column or the wall.

Eugène Viollet-le-Duc reduced buildings to their individual masonry blocks and the stresses transmitted from block to block. Structural mechanics envisions virtual—i.e., fictitious—cross-sectional cuts through structural entities and gauges the stresses acting upon these sections. This methodology is rooted in the supporting/supported dichotomy of classical philosophy.

Roofs, as supported elements, are ordered and geometric. Domed roofs are inherently built according to the principles of masonry construction. They are designed with spherical or circular forms, which simplify stress calculations and offer structural advantages. The symmetry of the supporting/supported framework leads to the underlying principles of the roof dictating even the floor plan. Domed buildings are hence marked by the extensive use of circular and square geometries. Geometry is conceptual; geometric constructions are artificial.

Yoh also utilized pure geometric forms early in his career. However, even back then, he was free from this kind of dualistic thinking. Consider, for example, the Ingot Coffee Shop (1977), where he explored the potential of the material of glass. He saw the envelope as the building’s only raison d’être. In doing so, he did away with the virtual sectioning. Moreover, he introduced a third material—namely, epoxy or silicone—at the junctures of the different materials, articulating it as a buffer and connector. He imbued these materials with special meaning by employing them not merely to compensate for deficiencies but to mediate the encounter between different things. What does reality entail for this kind of design sensibility?

-

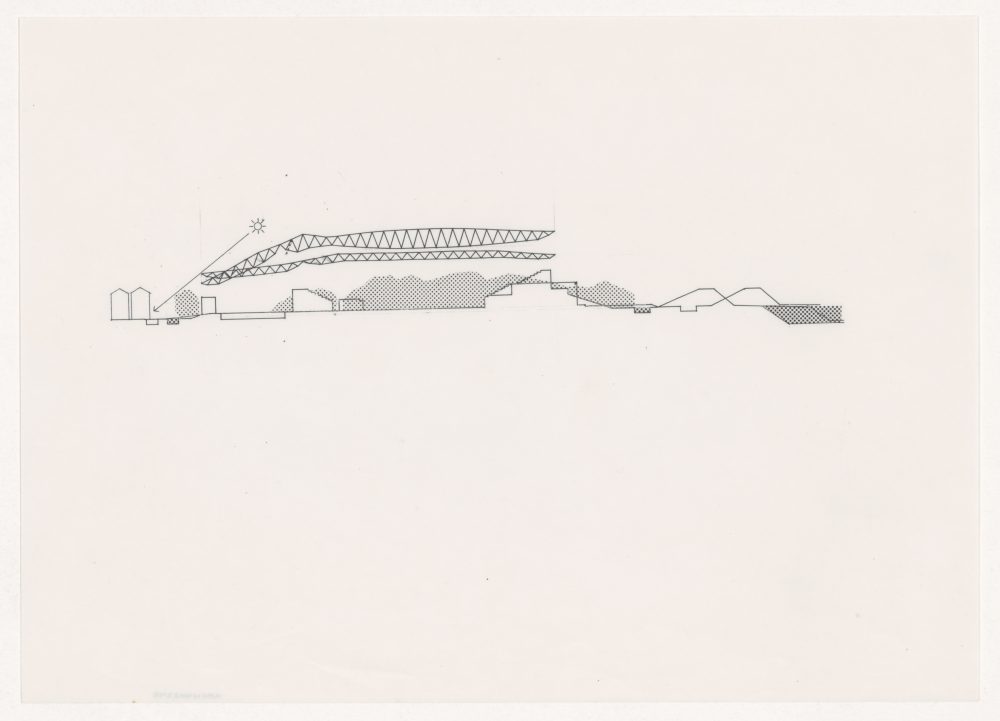

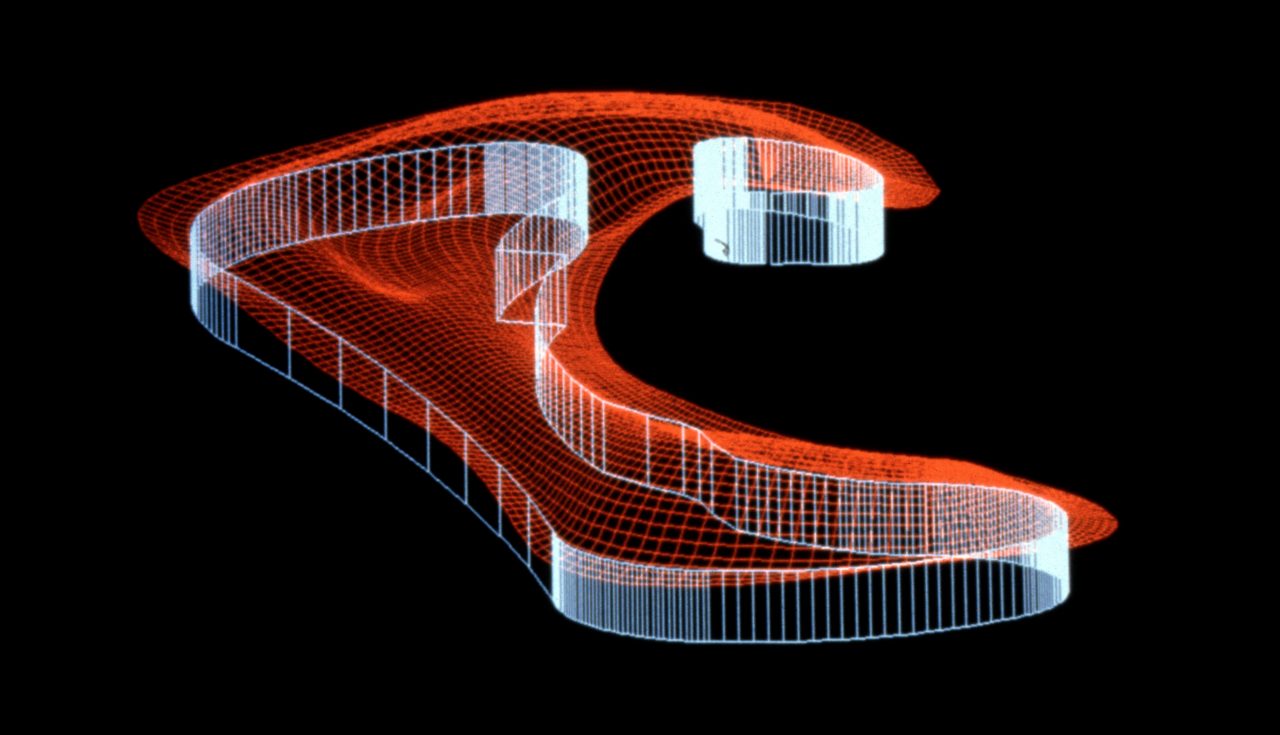

Uchino Community Center for Seniors and Children, computer-generated image. Shoei Yoh Archive, Kyushu University.

Reality

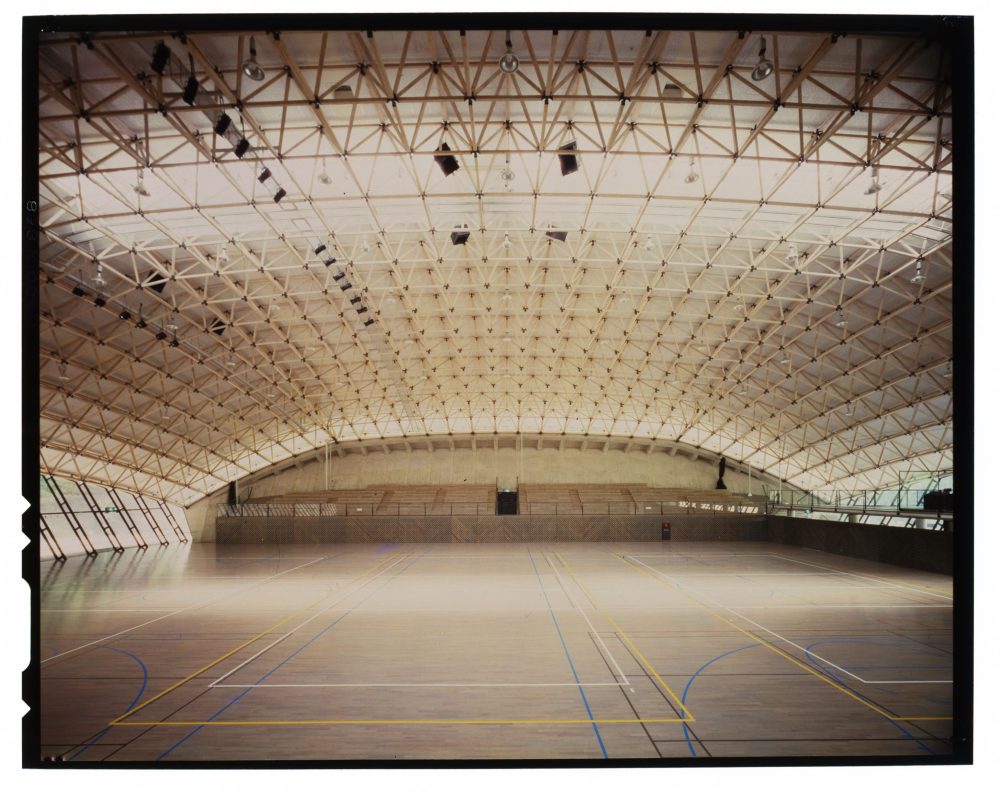

At the Naiju Community Center (1994) and the Uchino Community Center for Seniors and Children (1995), the floors are direct extensions of the earth. These floors are most notably configured as free plans, creating spaces somewhat similar to parks, where arbitrarily formed trails are later formalized into paths. The buildings can effectively accommodate the initial arbitrariness precisely because they were designed based on a rigorously rational set of procedures rather than an a priori geometric order.

The roofs resemble clouds or fog, drifting above the earth. They are reinforced concrete shell structures with richly articulated freeform surfaces. Unlike traditional vaulted or domed roofs, they do not have sections that cut through supporting/supported elements, as they are self-supporting structures. One could liken them to groves of trees or bamboo, with the columns representing trunks and the shells representing a dense canopy of branches and leaves. They provide shade for the townspeople to gather.

The buildings’ relationship to the earth is defined by their floors, and their relationship to the sky is defined by their roofs. While subjected to the various forces of both earth and sky, they harmoniously inhabit the space in between by passively bearing and actively converting and manipulating these forces.

-

Uchino Community Center for Seniors and Children. Photo: Shoei Yoh. Shoei Yoh Archive, Kyushu University.

Yoh thus freed himself from architecture’s traditional dichotomies of not only supporting/supported but also inside/outside, earth/floor, and artificial/nature. To avoid drawing lines between these things, he turned to concepts such as “mediating materials”, “points of equilibrium”, and “pleats”. The traditional dichotomies divide the world into two realms, and it has been understood that the reality of a building is only ensured through the reconciliation of these divides. Reality, as so conceived, inherently seeks to bring agreement to a bifurcated world. Yoh, however, does not try to ultimately reconcile the things that he deliberately separates at the start. In fact, he does not recognize dichotomous frameworks at all. For him, architecture is not about the inside/outside dichotomy; that is, it is not about enclosing an interior. Rather, architecture is and must be about establishing a new order within the site environment as a whole.

-

Naiju Community Center, interior view. Circa 1995. Photo: Yoshitake Doi.

-

Uchino Community Center for Seniors and Children, interior view. Circa 1995. Photo: Yoshitake Doi.

Emulating Nature

The JET Tower (1992) offers an experience of gazing down into artificial fog, created as an environmental art piece. This differs from the traditional aesthetic experience of viewing nature through a filter of fog that has formed in the landscape. However, natural fog and artificial fog are identical phenomena, at least when viewed on a micro scale. This experience embodies an aesthetic that combines sensory excitement with levelheaded objectivity. How does Yoh, the owner of this aesthetic sensibility, conceive reality?

-

JET Tower. Photo: Shoei Yoh. Shoei Yoh Archive, Kyushu University.

-

JET Tower. The observatory’s three-dimensional courtyard is infused by Fujiko Nakaya’s fog sculpture. Photo: Shoei Yoh. Shoei Yoh Archive, Kyushu University.

Yoh begins designing not from fiction but from the real. Things such as light, wind, gravity, and material are crucial to him. Capturing light in a uniform manner or rendering spaces with lattices of light is real to him. A long-span arch formed of linked pieces of thinned wood that settles in a certain position as it bends under gravity, a woven bamboo lattice that stabilizes in certain places as it sags under gravity, a large space-frame roof whose dimensions are adjusted according to the behavior of the stresses acting upon it—these are also all real to him. These things far transcend the plain and simple dimension of traditional realism. They are akin to phenomena such as rain, wind, and clouds, which are not so much physical entities as they are occurrences shaped as a result of a combination of various metrics such as temperature, humidity, and air pressure. Yoh’s buildings, too, are singular, real, beautiful occurrences that exist as a coalescence of diverse elements. One could liken them to the crystals that form when water vapor turns to snow.

Free and varied while conforming to physical laws as things in nature do, Yoh’s buildings are real and they are sincere. Moreover, the architect’s sincere philosophy of respecting the real and only the real, without relying on fiction, pervades his personality, his words, and his many brilliant works.

Among the handful of special features published on Yoh, there is an SD magazine feature issue titled “Shoei Yoh: 12 Calisthenics for Architecture” (January 1997). A parallel can indeed be drawn between architecture and calisthenics, or bodyweight training: buildings are fundamentally designed to support themselves, not external weights. Natural bodies behave in response to environmental factors such as gravity, humidity, temperature, and air pressure. Yoh’s buildings, while artificial constructions, behave like natural bodies.

Light

Optics was the cutting-edge science during the time of the philosopher Descartes in the 17th century. Scientists and philosophers alike put their minds to creating microscopes and telescopes. Exemplary of this is Descartes’ Dioptrics, which ties into and forms a whole with The World, Meteorology, and Treatise of Man. These writings lay out a concrete and detailed narrative describing the world as a medium for the transmission of light, opening up an interpretation of the universe, and hence also of nature, as a monism of light.

The Sundial Welfare Facility for Seniors (1996) features an enormous glazed atrium. Instead of confining the users of this elderly care facility, Yoh sought a solution that would allow them to receive care within an open, airy space while still protecting their privacy. This led to the construction of the spacious atrium. Since both its ceiling and walls are made of glass, nothing obstructs the transmission of light.

The atrium’s structure is entirely exposed on the exterior, making it hardly noticeable from the interior. It could be described as a selectively barrier-free design that allows light to pass through while concealing things that are visually undesirable. Yoh himself likens this to the relationship between the exterior buttresses and the interior view of the stained-glass windows of Gothic cathedrals. However, in my view, it speaks to the monism of light.

-

Sundial Welfare Facility for Seniors, interior view. Circa 1997. Photo: Yoshitake Doi.

-

Sundial Welfare Facility for Seniors, glass roof. Photo: Yoshitake Doi.

-

Sundial Welfare Facility for Seniors, roof structure. Photo: Yoshitake Doi.

Junichiro Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows speaks to the dualism of light and shadow. While portraying shadows, Tanizaki leverages this potent dualism to depict a fictional interiorized light, like that found in Romanesque churches, where light is funneled in through windows piercing thick, solid walls to emphasize the materiality of the stone; in Gothic cathedrals, where luminous stained-glass windows recreate heavenly realms on earth; or in Japanese rustic teahouses, where shitajimado [exposed lath windows] convey the ever-changing expressions of natural light. This dualism renders light as a symbol of nature or transcendence and a means of illumination and revelation.

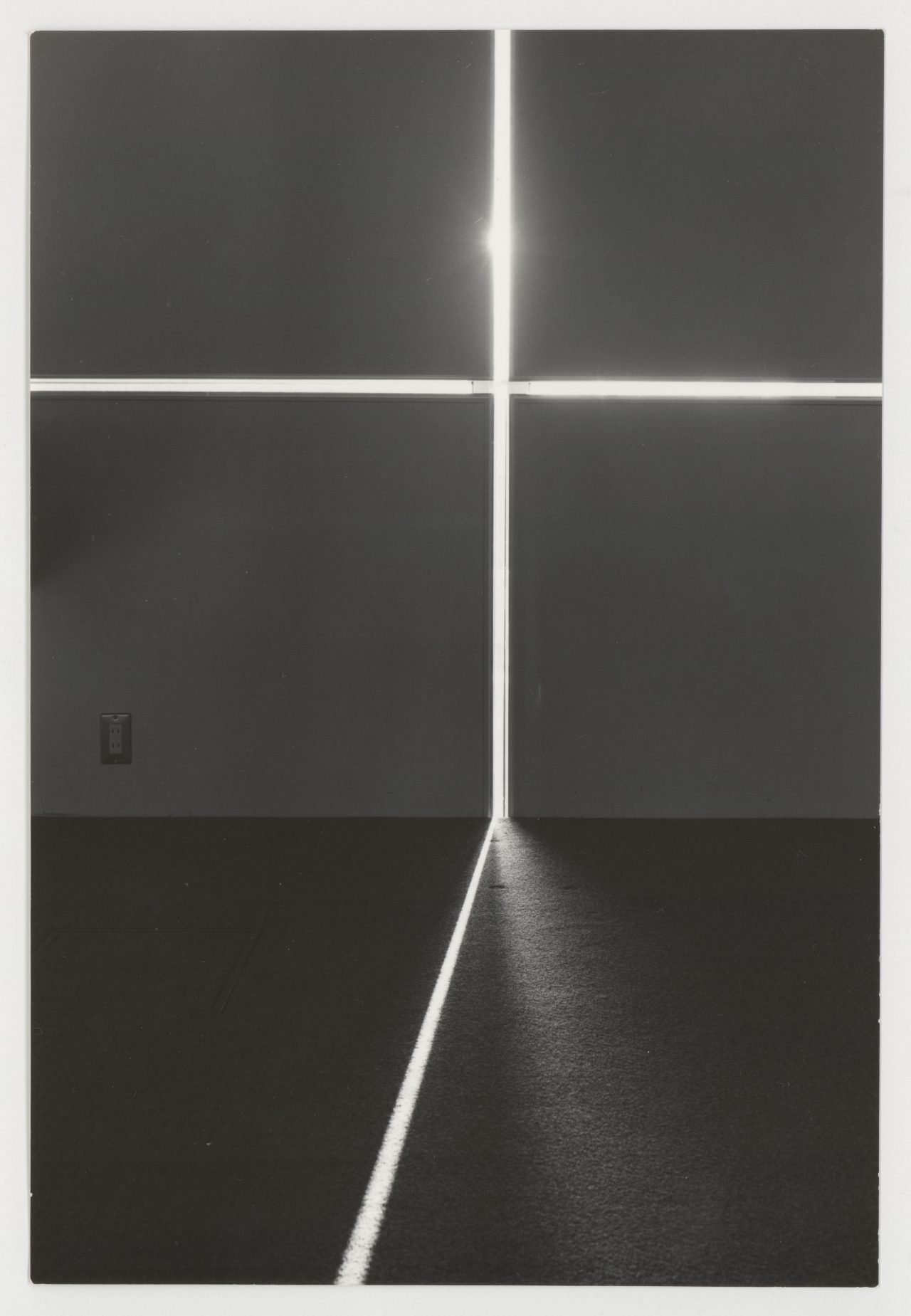

In contrast, Yoh constructs worlds that are filled with light and devoid of shadows. Consider both the Stainless Steel House with Light Lattice (1981) and the Sundial House (1984), where one can compare light of various intensities entering from different sides of the cubic interiors or observe light shining in from one slit at one moment in time and from another slit in the next. Light itself is the primary subject. These buildings can be seen as photometric devices of sorts, like prisms that deconstruct light into its components. A prism is a universal device that elucidates the natural world by enables one to examine light as it passes through a universal condition where two types of matter exist in juxtaposition. Yoh’s buildings, in a similar way, are microcosms that engage with real light itself.

-

Sundial House. Photo: Shinkenchiku-Sha. Shoei Yoh Archive, Kyushu University.

-

Sundial House. Photo: Shinkenchiku-Sha. Shoei Yoh Archive, Kyushu University.

Top image: Sundial Welfare Facility for Seniors, interior view. Circa 1997. Photo: Yoshitake Doi.

Yoshitake Doi

Born 1956. Architectural historian. Doctor of Engineering. Graduated from the Department of Architecture at The University of Tokyo. Withdrew from the doctoral program at The University of Tokyo with full credits. Held positions as a research associate at The University of Tokyo, associate professor at the Kyushu Institute of Design, and professor at Kyushu University before becoming an emeritus professor at Kyushu University. Studied abroad as a French government scholarship student at the École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Paris La Villette and Sorbonne University. French government-certified architect. Publications include Architectural Missions in the Age of Classicism (V2-Solution Books), An Imaginary History of Architecture (Sayusha), The Sacred in Architecture (University of Tokyo Press), Chikaku to kenchiku [Perception and Architecture] (Chuo Koron Bijutsu Shuppan), Academii to kenchiku ōdā [The Academy and the Architectural Orders] (Chuo Koron Bijutsu Shuppan), Kotoba to kenchiku [Words and Architecture] (Kenchikugijutsu), Tairon: Kenchiku to jikan [Discussion: Architecture and Time] (Iwanami Shoten), and Kenchiku kiiwādo [Architectural Keywords] (editor and author, Sumai no Toshokan Shuppankyoku), among others. Has also published numerous co-authored books. Translated publications include Pierre Lavedan’s Histoire de l’urbanisme à Paris (Chuo Koron Bijutsu Shuppan) and David Watkin and Robin Middleton’s Neoclassical and 19th Century Architecture, vol. 1 and 2 (Hon no Tomosha). Awards include the Architectural Institute of Japan’s AIJ Book Award and AIJ Prize (Research Paper).