Series Windows of Japanese Modernist Architecture

The Diversity of Windows in Kiyonori Kikutake’s Serizawa Literary Center (Serizawa Kojiro Memorial Museum)

25 Dec 2024

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Columns

- Essays

Numazu, Shizuoka—the birthplace of Kojiro Serizawa, the author known for works such as Ningen no Unmei [The Fate of a Human]. Nestled in a pine forest beside Suruga Bay is the Serizawa Literary Center (now the Serizawa Kojiro Memorial Museum, 1970), designed by Kiyonori Kikutake, Architect & Associates. Architect and researcher Tatsu Matsuda walks us through this lesser-known gem of the Metabolism movement, which features a variety of windows within its simple composition of cores formed from clustered walls.

Four Pillars in the Pines

Standing quietly on the Ganyudo Coast, at the eastern fringe of the Senbon Matsubara [Thousand-Tree Pinewoods] that follows the coastline of Suruga Bay for about 10 kilometers from the Tago Inlet, is a literary monument titled Kaze ni naru hi [Monument That Sings in the Wind] (1963). The reinforced concrete monolith is split by a narrow vertical off-center slit, which was originally topped with a metal sculpture by preeminent avant-garde postwar sculptor Ryokichi Mukai (1918–2010) that was unfortunately nowhere to be found at the time of my visit in 2024. The sound of the wind passing through the slit is superimposed onto a childhood memory of locally born author Kojiro Serizawa.

-

The Kaze ni naru hi literary monument designed by Masato Otaka.

The monument was designed by architect Masato Otaka—this I did not know. Although it is in a rather worn-down state, with some of its internal rebars showing on the surface, the slitted design cleverly makes use of the strong seaside breezes to evoke the sound of the wind. As I walk away from this monument with the sea at my back, a concrete mass soon comes into view, nestled between Mount Ushibuse on the right and the pinewoods on the left. This is the Serizawa Literary Center (now the Serizawa Kojiro Memorial Museum), designed by Kiyonori Kikutake, Architect & Associates.

I move in for a closer look. The building is composed of four large, tower-like cores. While they appear to be enormous solid pillars, they have fairly spacious interiors that house stairwells and galleries. The floor and ceiling slabs span between the four cores, but there are only two stories because the first story has a high 5-meter ceiling. The rooftop is designed as an observation deck that offers views out to the Senbon Matsubara and Suruga Bay. One of the cores has a long, narrow slit running down the center of its face. As the walls of the irregular heptagonal cores are all tall and narrow in proportion, the building brings to mind a Gothic verticality in its details, but not so much when regarded as a whole. It occurs to me then that its overall volume is scaled to harmonize with the surrounding pines: it blends in with the trees while still asserting its presence.

Tangible Metabolism

The Center was built in June 1970, right in the midst of the Japan World Exposition in Osaka, which began in March. By then, Kikutake had already emerged as the darling of the times: he had recently completed the Expo Tower (1969) at the exposition site, capping a decade during which he proposed numerous visions for the future, such as the Marine City; realized major works such as the Tokoen (1964) and Miyakonojo Civic Center (1966), one after the other; and advanced his personal design methodology through his seminal book, Taisha kenchikuron: Ka, kata, katachi [The Theory of Metabolic Architecture: Ka, Kata, Katachi] (Shokokusha, 1969).

This building may not particularly stand out when placed alongside the slew of projects he designed during that period. Yet, as I take my time walking through it, I begin to think that it may actually be a hidden Kikutake masterpiece. The space held up by cores is very much a Metabolist expression; it is similar to the parti of his Sky House (1958), where the living spaces are raised into the air by four piers, or his Tatebayashi Civic Center (1963), where the spaces are also supported by four cores but have additional intermediary columns. However, the Serizawa Literary Center lies between the two in terms of scale, offering a spatial experience that is distinct from both. Here, you can tactilely feel the distance from core to core, which are spaced neither too far apart nor too close together, giving you a real sense of the slab suspended between them.

One could go further to say that this building’s size made it ideal for Kikutake to connect his ideas to the architecture—or, to use his terms, to express the “ka” (principles), “kata” (order), and “katachi” (phenomena). That is, I believe it is the best place where one can truly experience these concepts all at once in a single building. And I feel that the designs of its windows speak to this.

Creating Openings Without Making Holes

Now, what do I mean by this? When you are at the Center, you actually do not really feel the presence of windows—or more precisely, windows made as holes in walls—because it is, in fact, a “hole-less” building. Normally, buildings have holes of some sort to allow the passage of light and air. Instead of making traditional “hole-in-the-wall” windows, Kikutake focused on creating walls that inherently formed openings. The clusters of walls form the cores, and these cores make up almost the entirety of the building, with the only other elements being the horizontal slabs that span between them.

I have identified three types of windows in the bold, yet simple architectural composition. The first type is the wall-slit window, found in the core housing the stairwell. Interestingly, this vertical fixed-glass slit window is intersected by a short horizontal slit near the top, forming a slender Latin cross when viewed in full from the outside. The design is a subtle nod to Christianity, which influenced Serizawa throughout his life. Important to note is that the window is expressed in such a way that it reads not as a hole in the wall but more as a gap between two walls. Ascending the spiraling stairway inside the core, I see two lights, resembling fishing buoys, hanging down through the central void of the stairwell from a cantilevered beam at the top. The stairwell appears to have been designed to evoke an undersea environment. As I climb a little further, the cross-shaped portion of the window emerges into view. Though not large, it is a dramatic and mystical space.

-

View of the cross-shaped slit window from inside the stairwell. -

Close-up view of the fixed-glass slit window.

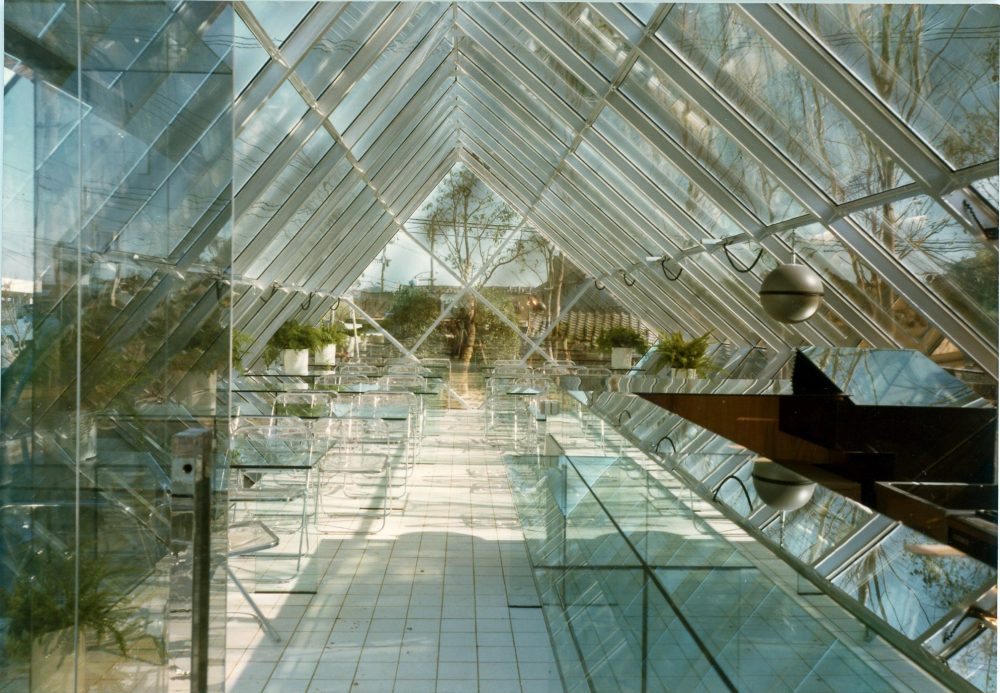

The second type of window is the inter-core window. On the first story, soft light filters in through the upper part of the gaps between the cores, filling the airy, high-ceilinged gallery that was originally planned as an exterior piloti space. Even airier, however, is the second-story hall. Here, you clearly get the feeling that the space is floating in the air. Cropped at the corners by the four cores, the hall is cross-shaped in plan, perhaps deliberately for the same reason as the wall-slit window. The ceiling, made of exposed cedar-board-formed concrete, is articulated with repeated V-shaped grooves that emanate from the cores and converge at the center. This intricate pattern, reminiscent of pine needles, gently guides the viewer’s gaze upward, enhancing the sense of lightness in the space. The inter-core windows on this story fill the full height from floor to ceiling. Although bracketed by slender casement windows and rather wide aluminum sashes, these gaping openings are otherwise free of obstructions and are visually filled by the pine trees outside. The airiness of the space is further enhanced when you stand in a position where you can see the wall-to-wall openings beyond the open doors of the cores. One could argue that the second story does not have any “windows” per se; it only has gaps that resulted automatically from having four cores. Once again, Kikutake created openings without making holes.

Vertical Rhythmicity, Disappearing Tricks, and Mixed Architectural Languages

The third type of window is what we might call the “normal” infill window. This is not to say that these windows at the Center are not interesting. Take, for example, the large 5-meter-wide opening composed of wood-sash windows set in wooden frames that backs the grand entrance doors. Its stacked wooden squares create a vertical rhythmicity. These intricately designed features—which, with the exception of the floor that was originally finished with vinyl composition tiles set in the same pine needle pattern as the ceiling, remain unchanged—establish a balance with the massive cores.

The current staff room, located beside the entrance, has a passage at the back that leads up to a mezzanine level. Hidden here is an approximately 2.5-tatami-mat-sized space styled in a Japanese manner—albeit with ceilings and walls of exposed concrete. The opening connecting this room to the central gallery is properly designed with three layers: from the inside to outside, these consist of double-sliding fusuma [cloth-faced wood-framed panels], double-sliding shōji [paper-faced wood-framed screens], and double-swing board shutters. When fully opened, these board shutters, which are also attached to the doorway below, fit perfectly into nooks in the walls of the chamfered corner of the polygonal core and become completely inconspicuous. While this same magic-trick-like contrivance can also be seen on the second story and around the other cores, it is only here that two sets of stacked shutters can be made to “disappear” together. This is a valuable feature because it indicates that Kikutake sought to minimize the number of concrete elements at the detail level that could distract from what originally were envisioned as abstract cores.

-

The staff break room on the mezzanine.

Another feature that caught my attention is the small prismatic window visible from the outside to the right of the entrance. It seems to me that a different architectural language has been mixed in at this one part of the building for some reason. Unlike the other ventilation windows, it is neither designed as a simple opening nor a recess, but instead clearly stands out on the exterior like a bay window. It was not originally equipped with any lighting fixtures either. While its purpose may be to shield views, it seems to have too much sculptural intent. If one had to explain it, perhaps it could be described as a late-Corbusian detail. It resembles, for example, the slightly protruding, upward-tilted window in the east wall of Le Corbusier’s Chapelle Notre-Dame du Haut (1955) and the window covered by a rotated concrete wall on the south side of the Convent La Tourette (1960). These features add a sculptural accent to the buildings’ exteriors while also bringing controlled light into their interiors. The member of Kikutake’s staff who was assigned to the Serizawa Literary Center project was a young Yuzuru Tominaga, before he became known as a Corbusier scholar. I am tempted to conjecture that the window was his idea, but for now, I will stop at simply pointing out the diversity of windows that this building presents.

Simultaneously Appreciating the “Ka“, “Kata“, and “Katachi“

As interesting as the other diverse examples of normal infill windows at the Center are, I would like to go back to the first two non-“hole-in-the-wall”-type windows. Both the wall-slit window and inter-core windows can be described as openings that were not expressly fabricated as windows but rather formed incidentally as a result of constructing the walls and, by extension, the cores.

The former window resonates with the slit of the Otaka-designed Kaze nina ru hi literary monument nearby. Whether this is by happenstance, I do not know, but one wonders if the deteriorating, seemingly neglected monument could be restored, as the literary monument and literary museum can be seen as serial works by the two Metabolists. As for the latter windows, these are formed from gaps that are distinct from the inter-pier gaps of the Sky House and inter-core gaps of the Tatebayashi Civic Center, as I mentioned earlier. The Serizawa Literary Center is medium-sized relative to the two and occupies an extremely rare size class among Kikutake buildings. To use Kikutake’s terms again, it can be said that typically, the smaller the building, the more perceptible the “katachi” (phenomena) becomes, while the larger the building, the more perceptible the “ka” (principles) becomes. As one becomes more perceptible, the other becomes less so. However, my impression from visiting the Center is that it is a place where you can tangibly appreciate the “katachi” (i.e., the phenomena in the space) while also conceptually appreciating the “kata” (i.e., the order of the spaces created by the cores) and the “ka” (i.e., the principles informed by Serizawa’s literature and the site’s context) all at once.

The three types of windows coexist in the building as a direct result of its being just the right size for one to be able to simultaneously appreciate the “ka“, “kata“, and “katachi“. The interestingness and diversity of the windows are what make me believe that the Serizawa Literary Center is a hidden masterpiece that holds a unique position in Kikutake’s oeuvre.

-

View of Suruga Bay from the second-story hall.

Tatsu Matsuda

Born 1975 in Ishikawa, Japan. Specialist of architecture and urbanism. Architect. Associate professor in the Department of Design at the Shizuoka University of Art and Culture. Completed a master’s degree in engineering at The University of Tokyo Graduate School of Engineering in 1999. Worked at Kengo Kuma & Associates before completing the advanced studies diploma program (Diplôme d’Études Approfondies, DEA) in urban and regional planning at Université Paris XII. Previously taught as an assistant professor at The University of Tokyo Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology. Publications include Kenchiku shisō zukan (The Visual Dictionary of Architectural Ideologies) (Gakugei Shuppansha, 2023) and Kigō no umi ni ukabu “shima”: Isozaki Arata kenchiku ronshū 2 (Arata Isozaki Writing as Architecture 2) (Iwanami Shoten, 2013) (editor and author of both). Works include the JAIST Gallery.

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Windows of Japanese Modernist Architecture

The Windows of Tomoya Masuda’s Naruto Cultural Center: A Faintly Bright Louvered Space

17 Jun 2025

Windows of Japanese Modernist Architecture

A Culmination of Sutemi Horiguchi’s Aperture Designs:

The Tokoname City Municipal Ceramics Research Institute (Tokoname Tounomori Research Institute)15 May 2025

Windows of Japanese Modernist Architecture

The Windows of Hiroshi Hara’s Awazu House: Spaces of Light Illuminating the Darkness

26 Apr 2024

Windows of Japanese Modernist Architecture

Windows of the Aichi University of the Arts

by Junzo Yoshimura and Akio Okumura:

The Concrete Science of Living with Nature19 Jan 2024