Series THE SAGA OF CONTINUOUS ARCHITECTURE

The Window is the Difference

between the Life and Death of a Space

11 Oct 2016

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Conversations

- Interviews

There are many things you can understand about a company’s image by looking at the way it makes use of windows and glazing. Hernan Diaz Alonso, who is known as the director of the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc) and the architect of many buildings characterized by their unique surfaces, shares his thoughts on the symbolic meaning of windows.

Yusuke Obuchi (hereinafter referred to as Obuchi): It seems obvious that digital technology has transformed not only technical aspects of windows but also our perceptions of windows. For you I thought this would be an interesting topic because all of your projects are nothing but windows to some degree, right?

Hernan Diaz Alonso (hereinafter referred to as Diaz Alonso): I would say holes, but okay. For the purposes of distinguished people they’re colored windows.

Obuchi: For you, what is the role of the window in your designs?

Diaz Alonso: You can trace the evolution of formal language in architecture through windows. If you start from the renaissance, modernism was the first time that the window was not just a hole, but also created a surface. Windows became part of the horizontal composition and vertical composition. In that way, windows have been really important.

Since the 1990s, all of us have been obsessed with surfaces and form and digital manipulation of all that. What we have realized is the notion of punctuation signifies the tradition windows have in architecture. Windows have become something else. The window has become embedded in the continuity of other things.

I’m much more interested in bubbles. I mean, it’s a window right? With a lot of these highly reflective surfaces that I work on, the window or the glass will become flush.

Obuchi: Right, that is another aspect of windows. Not about the geometry but the effect that they produce.

Diaz Alonso: Yes, absolutely. I am more interested in that. I’m more interested in the effect of the window than the geometry of the window.

Obuchi: The windows in your designs seem to be the smallest units of the overall geometry, and when they aggregate, they transform into something other than a collection of small windows.

Diaz Alonso: Yes. I’m very interested in the cellular logic of any form, so the transformation of windows is one language as part of one vocabulary that gets integrated. So I agree with you. I think it’s a good assessment. I think there is a scalar logic to it. To tell you the truth, the last two years have been very, very interesting in terms of glass and transparency. I’m very interested in not only the window but the idea of the capacity of transparency in the glass to really produce non-recognizable forms because through transparency and reflectivity, the forms start to change.

I’m interested in the new possibilities of curtain walls, for example. The curtain wall doesn’t need to be flat anymore. I have become interested in how you integrate the problem of windows or integrate the problem of glass into this kind of language. I’m less interested in the flatness. I don’t have a problem with having flat windows, but then we camouflage it with veils, for example. I like layers a lot and we work with them a lot.

-

TBA 2.0, 2011 ©XEFIROTARCH

Obuchi: Where does this come from? This fascination with making forms appear to be different than what they are? Are you interested in the physical aspect of a form that makes multiple visual experiences?

Diaz Alonso: I think that sometimes you have internal logic, but sometimes it’s like a reaction to external forces, so in many ways one could argue that the formal Project (with a capital P) has been driven by that idea of form and the iconic form and all that. I think this was another way of stating the problem of form in a way that is not divided by joint or shape but that is divided by effects on spheres.

What if we have a super-precise, defined geometrical form? What if we don’t want that? A part of the big argument that I think is an interesting one (and this is, I will say, fundamentally different in Japanese or Asian tradition, but I’m a Westerner and I operate in the Western world) is that in many ways we can argue that architecture as a cultural practice in the Western world exists in the renaissance.

And if you think about it, part of the desire throughout the renaissance was to achieve perfection through imperfection; through an imperfection mix. Now we have computers—which are perfect equations—so the geometry is perfect. I think there is a desire to produce imperfection out of perfection.

Obuchi: Right, which is very Eastern when you think about it. That’s what the Eastern tradition is about.

Diaz Alonso: I think there are certain disciplinary things. Some would say: let’s be less precise, let’s make it more vague, let’s make it more ambiguous. It’s just a little bit of a reaction to what it is, right?

I’m very interested in fashion. There is something very interesting about Japanese fashion. I think it is the most sophisticated fashion design in the world, conceptually and technically. It always takes a convention and screws with it. You grab a jacket and it’s basically just a jacket, and then a backpack that looks like a regular backpack. But it is designed to be empty, so you cannot put a lot of stuff in it. If you do, it deforms, and it looks like a weird thing, right? There’s something that fascinates me about that. The idea is that you take a convention and you make it unconventional so you achieve sophistication through imperfection.

I was joking with my wife on the phone. I bought her a bag and a pair of shoes and I said, “Honestly, if I walk in here with $100,000 I will buy everything because conceptually it’s so fascinating.” Now, I’m not so sure if people look good in these things or not, but as objects they’re extraordinary. There is something about that. Is this design? Glass is used to symbolize transparency, order, regularity, whatever, right? What if we make glass to be dirty, imperfect, and distorted, but at the same time sophisticated? So, in a way I think what I’m trying to do with that is not different than what designers are trying to do with high-end fashion.

Obuchi: I read somewhere that the origin of contemporary Japanese fashion comes from the traditional kimono. The kimono is very simple and basically all are the same size. All you need to do to wear it is wrap it around the body and then fold it to adjust its length. It’s how you modify it to fit to the body. It’s not deformed in the sense of how you described before, but rather in how you make it adaptive. Whereas in the Western world, the origin is the military. It’s a uniform. They are precisely tailored and standardized, so someone like me, when I buy, say, HUGO BOSS, it just doesn’t fit. Because my body does not fit the standard sizes designed for Europeans.

Diaz Alonso: Well, it doesn’t work. Japanese fashion unfortunately doesn’t work for me either! We’re talking about windows. Window companies are the future of that. How far can convention get you?

What are the possibilities for windows? What would happen if you did a whole building of windows and you saw more and more and more of these layers of envelopes like metal over glass? You would also see that the whole process is all about tweaking the glass. I think, in a way, part of the problem with the lack of evolution of architecture is sometimes a result of the companies who produce standard products. They’re too comfortable with the standards. I’m not familiar enough with how important it is in Japan.

Clearly, here in Japan there is a sense of innovation and appreciation for things outside the norm, much more so than in Europe and America right now. That’s an interesting thing because I think it’s the only way somebody like me can have a dialog with a company like YKK AP. If I were to work with YKK AP on a project of mine, nothing that they would produce would fit my project, so they would have to custom-make things for my project.

I’m also interested in the future of the industry, the future of the service, the business of creativity in the industry of creativity, how that works, and whether or not we see a future in that. Also, how are we going to integrate new mechanisms of production into it?

Obuchi: Are there any other places where you could explore the idea of making geometry that disappears or appears? Or staircases? Within the treatment of window elements or surfaces, what gives the most juice? Or can we kind of extract it personally?

-

Helsinki Library, 2012 ©XEFIROTARCH

Diaz Alonso: There is more than one way to read that in the sense that things are never as linear as they seem. I have a very curious mind and I have a very playful mind, so I like to play with things and see what happens. The truth of the matter too is that we have to deal with certain pragmatics. To develop certain projects, you have to have a client and the project needs to move ahead, so when you’re in a competition, you develop a project to a point, you send it, you lose, you move on.

I’m interested in dislocating natural states; in how you move pieces. That’s something I learned—to take an element and put it in a different place or change the scale. And then it’s like this kind of surreal effect moment. So that interests me. It interests me a lot. How you use architectural elements to produce rhythm and break the rhythm of something. I’m interested in challenging the form, but I’m not interested in challenging the concept of the window. A window is a window. You need windows and you need light. They don’t need to look like your mother’s windows.

Obuchi: But with windows, you often talk about (once again, a more technical question) how to get light into those spaces.

Diaz Alonso: The window is the difference between the life and death of a space. Windows make the difference between a good space and a bad space. You can go to a great hotel, but if the windows are too small, you’re going to feel like a prisoner. In the hotel where we’re staying now, the windows are great. You don’t want the window from the floor to the ceiling because it may scare you when you’re so high.

The window starts at the floor with something like a white fence so you can look out without fear. Windows are amazing. I think windows are also really important when you work with partitions and repetitions. For example, windows in a museum are not so important. They’re important, but in a hotel, in housing, and in a tower, they’re everything.

If you use a lot of glass, in modernism conventions, it means clarity—it means transparency. There is a symbolism attached to it, you know. It’s an interesting problem but I really think I’m fascinated with the relation between windows, glass, and the reflective method.

Obuchi: How much do you use a computer to make that reflectivity really precise? Or to create a certain unexpected reflectivity that you want to play with?

Diaz Alonso: It doesn’t matter. That’s the whole thing. It’s the relation between form and reflectivity.

Obuchi: The reflection produces an entirely different meaning.

Diaz Alonso: Yeah. You can control a lot with the computer. I always feel that the computer produces a different one than the one that will be the real one and that’s pretty cool too. Another thing that I find fascinating is the degradation and transparency of glass over time. You know, I’m interested in distortion and extrusion and how you start to make them. They are really interesting problems. You have to customize them. Real windows too.

They are very varied in terms of tone and coloration, but I think there is a very culturally amazing thing about how they mix. Right now, we are in a very globalized culture. An office building in Tokyo is not so different than an office building in San Pablo, but when you look at projects that are a little bit older (older buildings), there was a whole different idea about what windows were and what they meant in each culture.

It’s not only shapes, it’s depth. So I think there’s a lot to do there. If a very clever architect like Frank Gehry works with the standards, the standards become anomalies. My case is the opposite. Everything I work with is an anomaly. I use standard moments to produce weird things.

But today I think something that is very important about windows is how they define private and public space. They separate us, but at the same time, they allow us to connect the two. I work a lot with that too. I think there is a much more subtle complex relationship now between the public and the private and the role of mediation, because in a way, one could argue that our iPhones are windows.

-

PS1, 2005 ©XEFIROTARCH

When you think about it, the whole notion of technology has been defined by Windows and the position of Apple to Windows. I mean literally Microsoft. When they came out with a software they called it Windows. Windows are also mechanisms for communication, like window displays. That also interests me a lot.

To me, those things are fascinating. It’s interesting because before I came here to talk to you, I didn’t know how much I would be able to say about windows. Then we started talking, and I realized there’s already all of this already! My brain is thinking, “Oh!” All these other possibilities are interesting.

Obuchi: You spoke about how different cultures traditionally have different levels of privacy that register in window design. Maybe reflectiveness also plays an interesting role in this too. In social hierarchy, for instance. Shininess, for example, seems to represent wealth. Transparency, reflections, and opacity are all effects from a single glass material.

Diaz Alonso: Yeah. Another example is the glasses that can go from transparent to opaque. There is a whole series of new possibilities.

Obuchi: I can imagine if you look at it one way, it’s transparent, but because of the reflective qualities, from another way, it becomes opaque.

Diaz Alonso: Yes, I think the surface of the window is also important. The floor is one thing. The moment that you put a little bit of curvature in, the reflection will change, the transparency will change, and distortion will come into play. If they curve it even more and if you do doubly-curved glass, it becomes a whole kaleidoscope of possibilities. I also wonder what the relation is between the transparent surface and the frame. For my own work, my main problem has always been the frame because the geometry of the frame is too prescriptive for me. I love windows, but the idea of the predetermination of a frame is a major problem.

Obuchi: That’s interesting because it’s a great way to animate the building. Once you make a curvature, it certainly produces a different visual effect, especially when you walk in front of it. It appears as if the surface is moving by itself.

Diaz Alonso: There is a significance the window has in our society and in our architecture. I have a simple theory about this. I’m probably wrong, but I think it came from banks. Look at banks from the nineteenth century until the 1930s. Or a temple or church entrance. They were made of heavy stone or brick. Solid. The message is, “We are solid.” At some moment, banks became all glass, transparent. They go, “We’re transparent. We are dynamic, we are modern.” Now it’s irrelevant because it’s about ATMs.

It’s all online, so banks don’t invest in buildings anymore. Banks don’t make symbolic buildings anymore. I have a feeling that money and offices blend into the same logic. I think it’s also a very important view of the office. I mean the notions of the corner office, the glass office, and the window office.

There is also something interesting about how the notions of glass and curtain walls became symbols of money. They never became symbols of political power. They’re symbols of monetary power. Political power is still expressed through heavy stone. Most government buildings are heavy. It’s an interesting idea; glass equals transparency and money and dynamism. Like the Apple Store.

Steve Jobs wanted to make it all about glass without seams because it was about being simple and clean. The apple is what Apple symbolizes. They use the gigantic glass as a way to produce a message. Historically, windows have been symbols for architecture. It’s almost like an alphabet; like a signature of a society, of a culture, of an architect.

Obuchi: It would be interesting to study how companies represent their image through the use of glass and windows.

Diaz Alonso: They all do it. Glass symbolizes sophistication and sleekness.

Obuchi: So the window is life and death for companies?

Diaz Alonso: Yeah. The window is the difference between the life and death of a space, yes. You do it wrong, you’re killing the space. You do it right, you give it life.

Obuchi: I enjoyed our talk on the window today. Especially considering that that no one seemed to expect an intellectual discussion about windows.

Diaz Alonso: No, but it’d be like if you had suggested we talk about shoes. You might think, “What can I say about shoes?” But then you’d realize you’ve been buying shoes all your life.

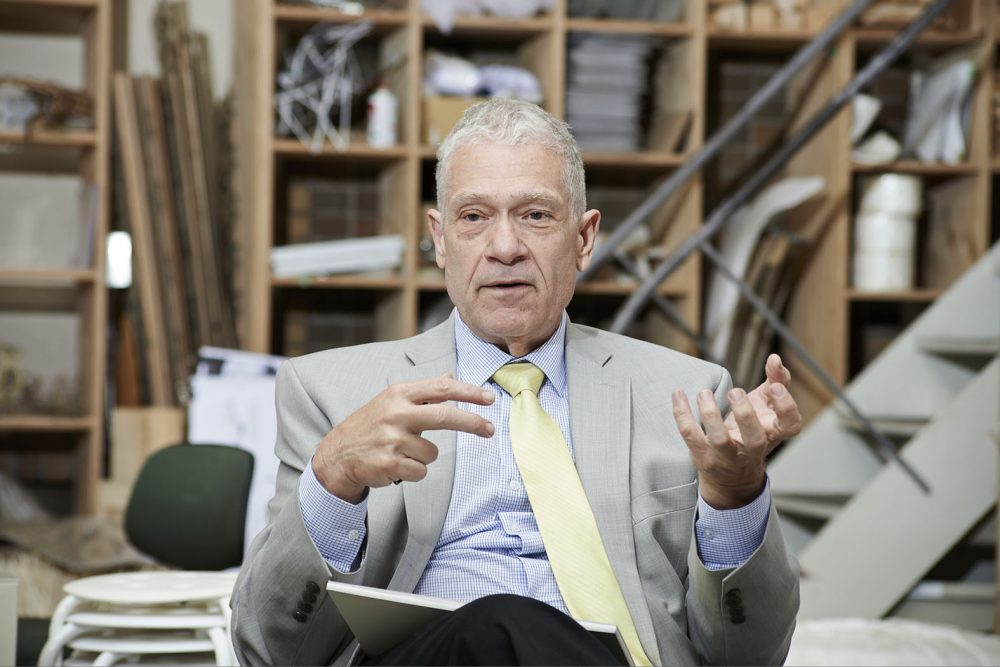

Hernan Diaz Alonso

Hernan Diaz Alonso is the director of SCI-Arc and is principal of LA-based architecture office Xefirotarch. In 2005 he won MoMA PS1’s Young Architects Program (YAP) competition, and he received the Educator of the Year Award from the American Institute of Architects in 2012. In 2013 he received the AR+D Award for Emerging Architecture and a Progressive Architecture Award; both awards were for his design of the Thyssen-Bornamiza Pavilion/Museum in Argentina. Diaz Alonso’s designs have been featured at the London Architecture Biennale, the Venice Architecture Biennale, and at ArchiLab in France. His work has been included in exhibitions by the New York MoMA, SFMOMA, and the Art Institute of Chicago. As an educator, Diaz Alonso has received the Louis I. Kahn Visiting Assistant Professorship from Yale University. He was a Design Studio Professor at Columbia University’s GSAPP, and is also an architectural design professor at the University of Applied Arts Vienna.

http://www.xefirotarch.com/

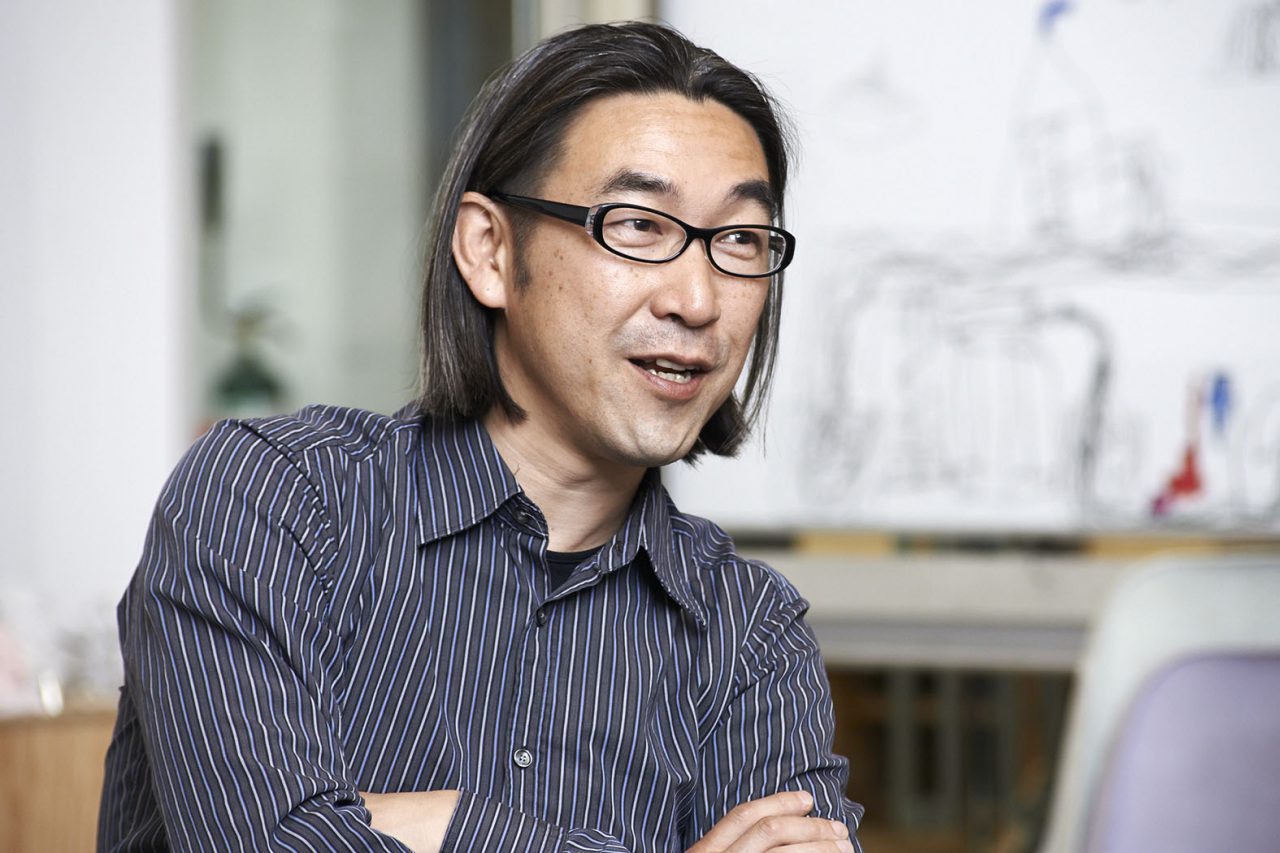

Yusuke Obuchi

Born in Chiba Prefecture in 1969. University of Toronto Department of Architecture from 1989-1991. Roto Architects from 1991-1995. Graduated Southern California Institute of Architecture in 1997. Completed Princeton Graduate School Master’s Course in 2002. RUR Architecture from 2002-2003. Course Master, AA School from 2003-2005. Director, AA School Design Research Lab from 2005-2011. Instructor, Harvard Graduate School of Design in 2013. Visiting Associate Professor, Princeton Graduate School from 2012-2013. Project Associate Professor, The University of Tokyo from 2010-2014. Associate Professor, The University of Tokyo from 2015-present.

http://t-ads.org/

http://obuchi-lab.blogspot.jp/