Series Danish Architects Serial Interviews

A Conversation with Johansen Skovsted Arkitekter

12 Jul 2023

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Interviews

- Landscape

On the occasion of the “Windowology: New Architectural Views from Japan” currently being held in Copenhagen, we conducted a series of interviews with four Danish architects in cooperation with the VILLUM Window Collection, the venue for the exhibition.

Johansen Skovsted Arkitekter, an up-and-coming firm based in Denmark, has already earned a variety of accolades in the eight years of its operation. Their projects such as Tipperne, where they proposed new structures for a bird sanctuary, and Skjern River, where they transformed disused pump stations, offer fresh ideas for how we can engage the natural environment through architecture. We spoke with founding partner Søren Johansen at their shared office space in Copenhagen to learn more about their work.

You have developed a number of unique projects that are deeply related to their environmental context. For example, perhaps your best-known project, Tipperne (2017), is located in a bird sanctuary that is an important stopover site for migratory birds. Could you tell us about the site?

Tipperne is in Ringkøbing-Skjern, a municipality situated on the North Sea coast in the western part of Denmark. To our knowledge, it’s the survey site of the longest-running bird count in all of Europe. It forms part of a small, flat peninsula inside a lagoon that features a very dynamic landscape with quiet waters formed just through the accumulation of sediment transported by a river.

-

Landscape 03 – Ringkøbing Fjord : ©︎Johansen Skovsted Arkitekter

Already in the late 18th century, the land was set aside as public property, and regulations were later introduced to protect it as a nature reserve. The site remained closed off except for researchers, and the public was only allowed special access to certain parts of it during specific periods of the year. The Danish Nature Agency decided to team up with a Danish architecture philanthropic association called Realdania to see if the site could be opened to the public without disturbing the wildlife. Our assignment was to design the facilities needed for this.

How did you become involved in the project?

In 2017, Realdania held an open call for architecture teams to take part in projects in areas of Denmark that needed to undergo a transformation from agricultural production to experience-based tourism. Sebastian, Christoffer Thorborg, and I applied together with Bertelsen & Scheving Arkitekter, where I worked at that time, and we had the luck to be chosen. I suppose we were a bit of a wildcard for them, because back then we didn’t even have an office, and we only had two small built projects and a competition proposal as references.

What did you design?

We designed a new bird watching tower (Tower), as the original one used by professional bird counters since WW2 wasn’t structurally sound enough to be opened to the public. We also renovated a field station used for studying the wildlife (Research Station) to serve both professionals and the public. Although this wasn’t part of the original assignment, we also proposed a bird hide (Hide), which is a small steel structure for observing the wildlife up close. We wanted to allow visitors to walk into the landscape to be closer to it, in addition to looking at it from a long distance through the telescope in the Tower.

Could you tell us more about the ideas behind the Tower?

Since the site is right on the west coast of Denmark, where it’s very windy and the air contains a lot of moisture, we wanted to make something that responds to the intense, dramatically changing atmosphere. Another idea we had, also based on an observation of the landscape, was to keep the horizon intact, as it’s the most dominant feature of the site. So, we tried to make an open, see-through structure that is as slender as possible.

-

Tower 06 : ©︎Rasmus Norlander

As the environment is also very salty, we had to use materials that could withstand weathering. We turned to electricity pylons and other galvanized steel structures made using traditional methods for ideas to work with, and found that if you use steel angles, they make sharp shadows, but if you use cylindrical steel bars, they appear very slender and create a much softer and lighter expression because the light bends around the surface. We looked around for manufacturers who handle structures of this kind and eventually found one quite close to the site. So, the Tower’s construction is truly based on an industrial production method. When designing it, we had to make sure every nut and bolt is in the correct place and plan everything because you can’t make any changes after they galvanize the components.

-

Section 1 at Carl C factory space – Tower : ©︎Johansen Skovsted Arkitekter

Why did you prefer to make it using a traditional method?

I wonder if “traditional” is the right word. It was more about using commonly available techniques. The factory that we worked with normally produces telecom masts and other such structures, which, if you go and see them, you will notice are actually much more refined than the electricity pylons that you see around everywhere.

Were budgetary constraints also a factor in your decision to take this approach?

Yes, the budget was quite limited, so our thought was basically that we should work very closely with the manufacturer to ensure that our design would be optimized for the techniques that they usually use. We actually were positively surprised by how much advice they had to offer about the structure, and I think that happened because we had pretty much incorporated all their usual techniques. So, even though the structure may seem complex, it was relatively simple for them to build, and this worked out well for keeping the costs within budget.

The very slender expression of our design also worked well with lowering the costs. If we had adopted a design approach that involved adding to the structure, we would have needed to use much more material.

But this delicate structure must still be quite strong considering how intense the weather conditions can get.

Although it looks fragile, the structure is actually very steady. It turned out to be even steadier than the kinds used for military radars. You can imagine just how steady it has to be since the professional bird counters need to be able to use the telescope to see how many eggs there are in a nest several kilometers away. This stability is achieved by the balustrade, which is composed of very thin round steel bars measuring only 22 millimeters in diameter. The balustrade not only prevents you from falling out of the stairway but also takes the lateral wind loads and transfers them to the foundations through these very slender steel bars, which act like the tension cables of a tent.

If what you wanted was an open structure, why did you cover it with sliding shutters at the top?

The glass shutters are only for when it’s windy. They allow the telescope to be used for 360-degree observation while keeping it sheltered from the wind. Because the telescope has to be able to pan, we didn’t put columns in the corners. This is also why we made the four sliding shutters on each side. We only needed three sets of these shutters because we found the triangle to be the optimal shape that allows the telescope to cover all the directions.

-

Viewing platform 01 – Tower : ©︎Rasmus Norlander

What did you think about with regard to how the different structures on the site relate to one another?

We wanted the elements to have some relationship to each other since the landscape here is so open and you can see all of them at once. However, we didn’t want them to display a very strong architectural signature, as we felt they would become too dominant in the landscape if they were too much alike. So, we decided to relate the Tower to the sky and the Hide to the ground and the vegetation around it.

-

New pond by the bird hide – Ringkøbing Fjord : ©︎Johansen Skovsted Arkitekter

We made the Hide out of corten steel to relate it to the ochre colors in the water of the small ponds on the site. Its leaning triangular form relates to the prevailing westerly wind. You can see the plants around it leaning away from the wind in the same way. We were also looking to keep it small, as we wanted it to have a lightness to it. This is why it doesn’t touch the ground and instead simply rests on the profiles that hold it together.

-

Hide in landscape 01 – Hide : ©︎Rasmus Norlander

It seems that these designs were very much guided by their relationship to their surroundings.

It was important for us that they would be perceived as things that are a natural part of the place. We wanted them to be related to various elements that are common to the local landscape, such as grain silos and electricity pylons, and be seen in the same way.

Another one of your site-specific projects is Skjern River (2015), which involved converting three pump stations. Could you tell us about that project too?

The Skjern River is the largest river in Denmark. Over the centuries, it created a delta landscape featuring a mix of marshes, meadows, winding channels, and shallow lakes, which led to the vast lagoon where Tipperne is located. In the 1960s, however, the downstream portion of the river was reclaimed and straightened out to be developed as agricultural land. That was when the pump stations were built.

-

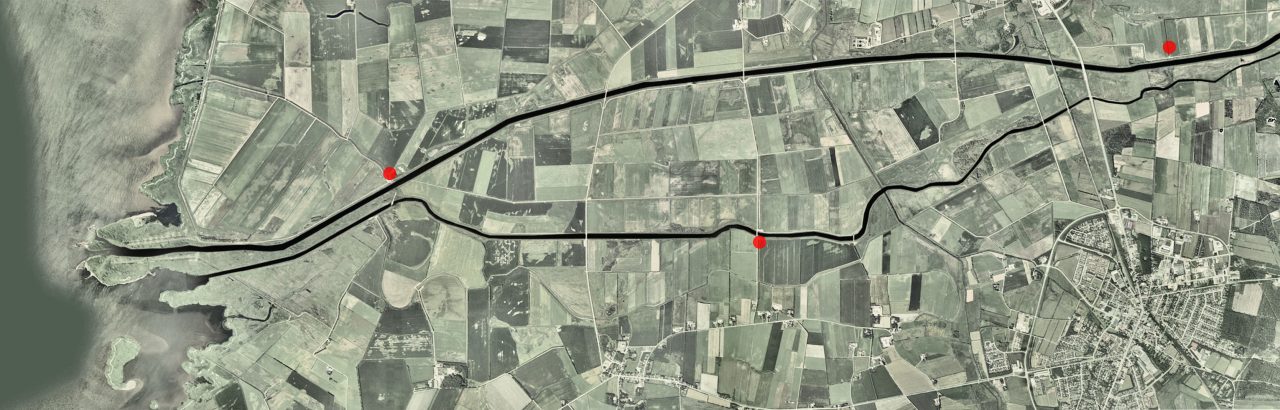

Area plan after the restoration of the river basin – Red dot indicates position of pumpstations -

Area plan before the restoration of the river basin – Red dot indicates position of pumpstations

But then a lot of problems occurred as sediment was washed out by the pump stations and by the drainage channels built to prevent the river from overflowing. Many fish and birds died in the lagoon. So, the Danish government decided to restore the river, and in 2002, a large part of the delta was once again returned to its original state. Much of the river and its wetlands are now protected, and the ecosystem has recovered. In 2013, the municipality and Realdania held a tender for an architectural team to repurpose three of the pump stations as recreational and tourist attractions for the community, and we won.

-

Pump station North 01 : ©︎Rasmus Norlander

How did you tackle this project?

The idea was to compose each of these pump stations so that they would still appear as singular objects in the landscape. So, this is the same approach that we used at Tipperne. We wanted to provide people who interact with the buildings with a memorable spatial experience without disturbing the landscape.

For Pump Station North, which is the largest of the three pump stations, we converted the interior into an exhibition space and added a structure on top to create a partly covered viewing terrace. The new structure reflects the relief pattern of the original building’s concrete façade but is instead made of wood.

-

Pump station North 03: ©︎Rasmus Norlander

We decided to make a strong compression in the stairway leading to the terrace so that the space would open up again when you emerge at the top. This stairway transitions from a very dark and narrow space to a bright space illuminated by translucent glass fiber panels. As the landscape is very open and flat, if we had made an open stairway, you basically would have been able to finish experiencing it before you reached the terrace.

-

Stairwell – Pump station North : ©︎Rasmus Norlander

The structure on top is cross shaped, and it divides the terrace into four separate areas. On the south side, you have a view towards the river and the more natural landscape. On the north side, you have a view of the agricultural landscape with canals and fields. And then to the sides, you can look down the long path along the dyke that used to contain the water during a period from 1960 to 2000. So, the views in each direction are quite different in character.

-

Roof 02 – Pump station North : ©︎Rasmus Norlander

-

Roof 01 – Pump station North : ©︎Rasmus Norlander

The structure essentially marks the boundary between the rewilded landscape and cultivated landscape.

Exactly. And it also serves as a framing device, as the walls help you focus on each view. Even though the experience is really simple, we divided it into small pieces so that you can appreciate each view one at a time.

As with Tipperne, I find it unique how your client of this project wanted to develop a tourist destination of sorts by making use of the site’s existing features rather than creating a new attraction from scratch. And yet, there is no obvious landmark, like a huge waterfall, for example.

I understand why you might think, “Why would anyone go to this flat piece of land to have an experience?” But this is Denmark—we don’t really have any waterfalls. [laughter] This is the kind of nature that we have. Maybe it’s not as powerful as the big mountains in a place like Norway, where the landscape itself can give you a great experience anyway. The difference here is that you have to open up to the landscape a bit more. It’s also easier to disturb though, so you must be very careful to keep the expression of the intervention quite quiet so as not to ruin it. We’ve made these architectural elements, but they aren’t the actual attraction; the focus is on the landscape.

Johansen Skovsted Arkitekter was founded by Søren Johansen (b. 1981) and Sebastian Skovsted (b. 1982). The office seeks to synthesize ideas, techniques, and manufacturing methods in ways that connect contemporary building processes and materials with timeless architectural values, and works particularly effectively in contexts that require a delicate response to the existing architecture and landscape.

Søren Johansen studied at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts Schools of Architecture, Design, and Conservation (KADK). Sebastian Skovsted studied at the KADK and Delft University of Technology (TU Delft). They have previously taught at the KADK Institute of Architecture and Technology.

Top : ©︎Rasmus Norlander