The Criminology of Windows

10 Dec 2019

According to sociologist Georg Simmel, windows have two fundamental meanings. Firstly, they create a unilateral connection between the inside and outside. Secondly, they constitute a path that exists for the sole purpose of the eye.

However, there are some acts that resist this fundamental “principle”. See the photo below for an example.

In other words, an act that violates the social consensus over the role of windows constitutes “deviant behavior”, and as such we call it a “crime” when the act is subjected to (formal) punishment.

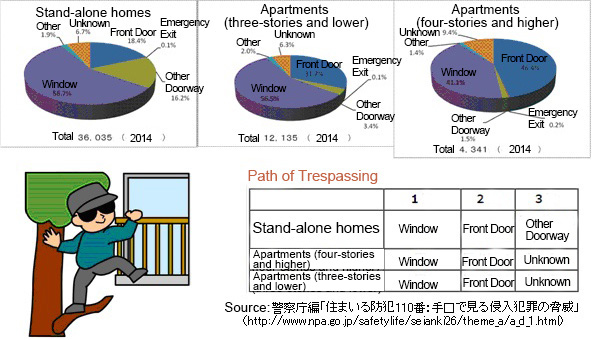

Windows as a path for trespassing

According to statistics compiled by the National Police Agency of Japan (NPA), windows ranked top among “paths for trespassing” for household burglaries across all types of housing. This means that people looking for a path other than the one meant solely for the eye, namely for crossing from the outside to the inside, will know a good thing when they see it.

A Look at CPTED(Crime Prevention through Environmental Design)

In an attempt to deal with these windows as a path for trespassing, a project aimed at improving the physical security performance was jointly implemented by the government and private sector, achieving a certain amount of success (http://www.npa.go.jp/safetylife/seianki26/theme_b/b_c_1.html [in Japanese]) However, there is also concern that these physical crime prevention measures inhibit the other role of windows, namely, that of connecting the inside and outside, and “fortifying” our houses in the name of “safety and security.”

“Broken Windows” as a metaphor

In the field of criminology, apart from the “window” as an element of the physical environment, the image of the “broken window” is becoming dominant as a theoretical metaphor.

As seen below, if one fails to deal with minor disorderly acts such as littering and graffiti, other illegal activities will follow; eventually, people will become desensitized and stop paying attention to such ʻbroken windows,’ and they will be left unrepaired. This leads to a further decline in the security capabilities of the whole community as well as an increase in more malicious crimes and criminals; this, in a nutshell, is the “broken window theory.”

This theory was originally derived from observations of slum areas in the United States. However, there is some disagreement about what kinds of countermeasures would be most appropriate under these circumstances.

One of the ideas proposed is known as the “Zero Tolerance” policy: it states that police should not overlook even the smallest acts of deviance, and should enforce strict regulations on them. If this policy is taken too far, however, it may generate public backlash against overzealous crackdowns, or encourage discriminatory policing, both of which are indeed major social problems in the U.S. today.

I myself believe that for official agencies like the police, it is more desirable to support proactive, voluntary initiatives on the part of citizens that “ensure their own security through their own knowledge and strength,” rather than by intensifying crackdowns.

Expanding “voluntary crime prevention activities” of local residents

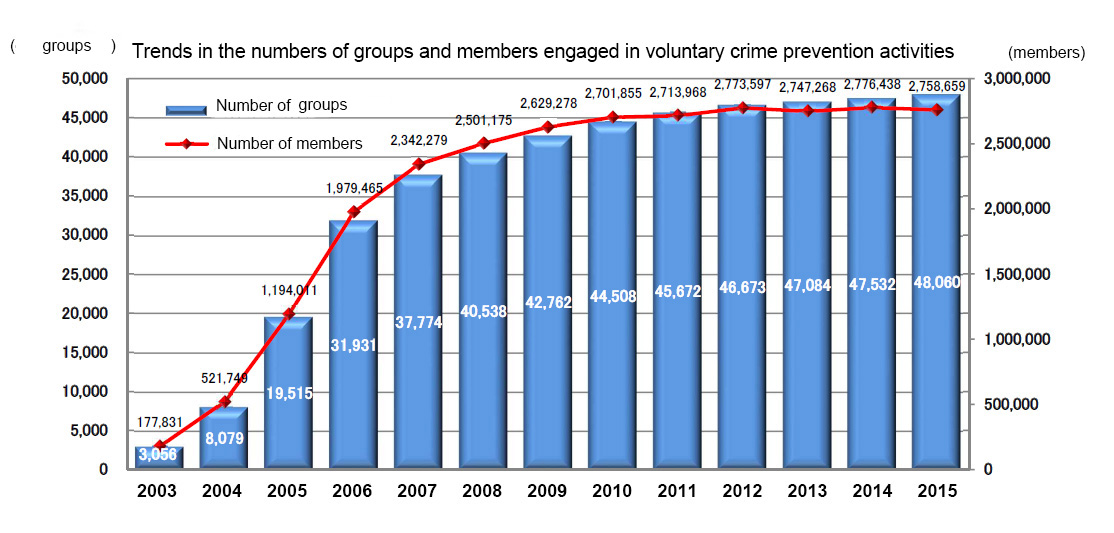

In fact, over the past ten years, voluntary crime prevention activities by local residents have spread to various regions as indicated in the graph below.

-

Trends in the numbers of groups and members engaged in voluntary crime prevention activities (Statistics obtained from police in every prefecture)

However, as these activities mainly involve movement in an outdoor setting, it has always been difficult to obtain exact information about them or to share information between members.

Development of the “Kiki-gaki Map”

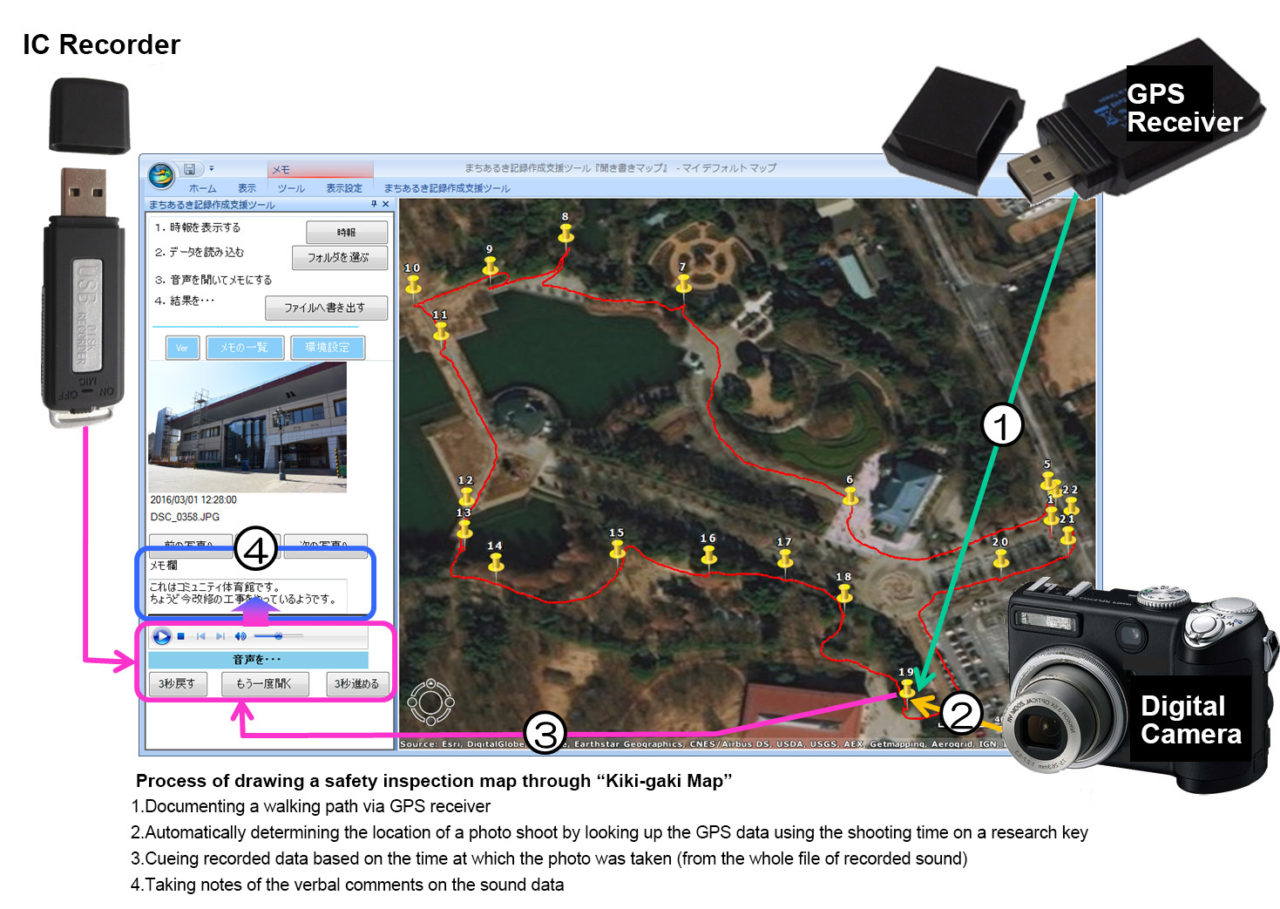

For this reason, we developed software called the “Kiki-gaki Map,” by making use of recent technologies such as GPS to map out the results of walking around neighborhoods for safety checks.(http://www.skre.jp/KGM_3100_top/KGM_top.html [in Japanese])

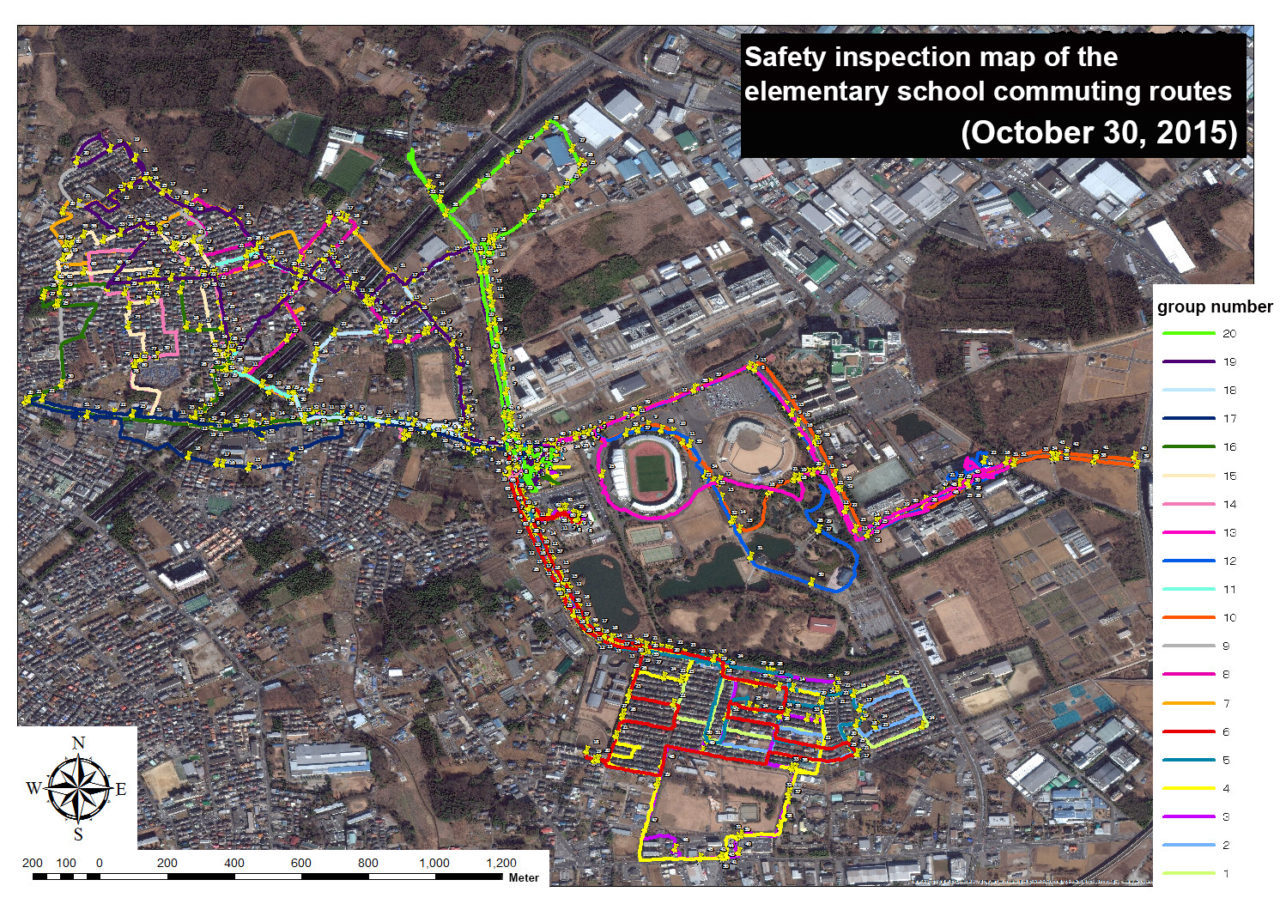

In fiscal year 2015, as one of MEXT’s model projects, we initiated the safety inspection maps for elementary school commuting routes by making use of “Kiki-gaki Map”. In this model school, all the 4th grade students completed a series of fieldwork with three gadgets (GPS receiver, IC recorder, and digital camera) and created safety inspection maps by converting that data and printing it out. (http://qzss.go.jp/news/archive/gis_161018.html [in Japanese])

If we export the data collected through “Kiki-gaki Map” to a general purpose geographic information system, a large panoramic window—a safety inspection map covering the entire area based on the data collected by each of the groups separately—will appear.

With this, members can share security information pertaining to the neighborhood in the form of maps with a minimum expenditure of time and money. This is a tool that enables us to “visualize” the current state of a given area in a “panoramic” way.

Moving forward, I would like to support locals in solving problems through greater coordination among members based on their respective situations by continuing to improve this “Kiki-gaki Map” and encouraging its widespread adoption.

Conclusion

In closing, I would like to conclude with the suggestion that the act of repairing “broken windows,” in a metaphorical sense, is also to create a “window” of cooperation that connects people— or is perhaps an “opening” to do so.

Yutaka Harada

Born in 1956, Osaka. He holds a Ph.D in Criminology, with a specialty in Sociological Criminology. After graduating from the Department of Sociology, University of Tokyo, he joined the National Research Institute of Police Science. For two years starting in August 1986, he studied at the Center for Studies in Criminology and Criminal Law, University of Pennsylvania on the Fulbright Scholar Program. During this period he wrote a research paper entitled “Modeling the Impact of Age on Criminal Behavior: an Application of Event History Analysis,” and became the first Japanese national to win the Gene Carte Student Paper Competition of The American Society of Criminology. In August 2000, he received his Ph.D. degree in Criminology from the University of Pennsylvania. After working as chief researcher in the Crime Prevention Section at the National Research Institute of Police Science, he served as the head of the Department of Criminology and Behavioral Sciences from 2004 until March 2016. He has served in his current post since retiring. He is conducting a longitudinal analysis of crime and delinquency careers, a geographic analysis of crime using GIS, and an empirical crime analysis with an advanced approach, in addition to trying to make a civic contribution using the results of his research to give back to society by developing and sharing the field note-taking support software “Kiki-gaki Map.”

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Window Sociology

High-rise condos and windows—from functionality to scenery—

22 Aug 2019

Window Sociology

Societies and Fluctuations in Numbers of Windows—Some thoughts on the Question of “windows” During Times of Change

25 Jul 2019

Window Sociology

Windows and the Invisible Light

17 Jun 2019

Window Sociology

Windows as media

— why we find looking through windows intriguing?—24 May 2019