Series Japan Pavilion, The 15th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2016

Exhibition “Present State(ment)”

27 May 2016

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Interviews

“En: art of nexus” is the theme of the Japan Pavilion at the 15th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2016, one of the world’s largest modern architecture festivals. How are the exhibiting architects interpreting the theme? What are their ideas of the various forms of “windows” in architecture? We interviewed the architects and the venue designer by taking actual works as examples.

Could you explain your latest exhibition, “Present State(ment)” ?

Takeshi Hashimoto (hereinafter referred to as Hashimoto): The Prismic Gallery, the venue of this exhibition, is a gallery where exhibitions of young architects have been held continuously as its main feature, and it’s a great honor for us to have this opportunity. For “Present State(ment)”, we wanted to make it as an opportunity for reviewing what we have done, rather than exhibiting our current works and projects in detail. So what we did is to stay at the gallery for a while just before the exhibition started, which was called “the editorial room”, and we had a discussion there. The exhibition shows the result of that discussion.

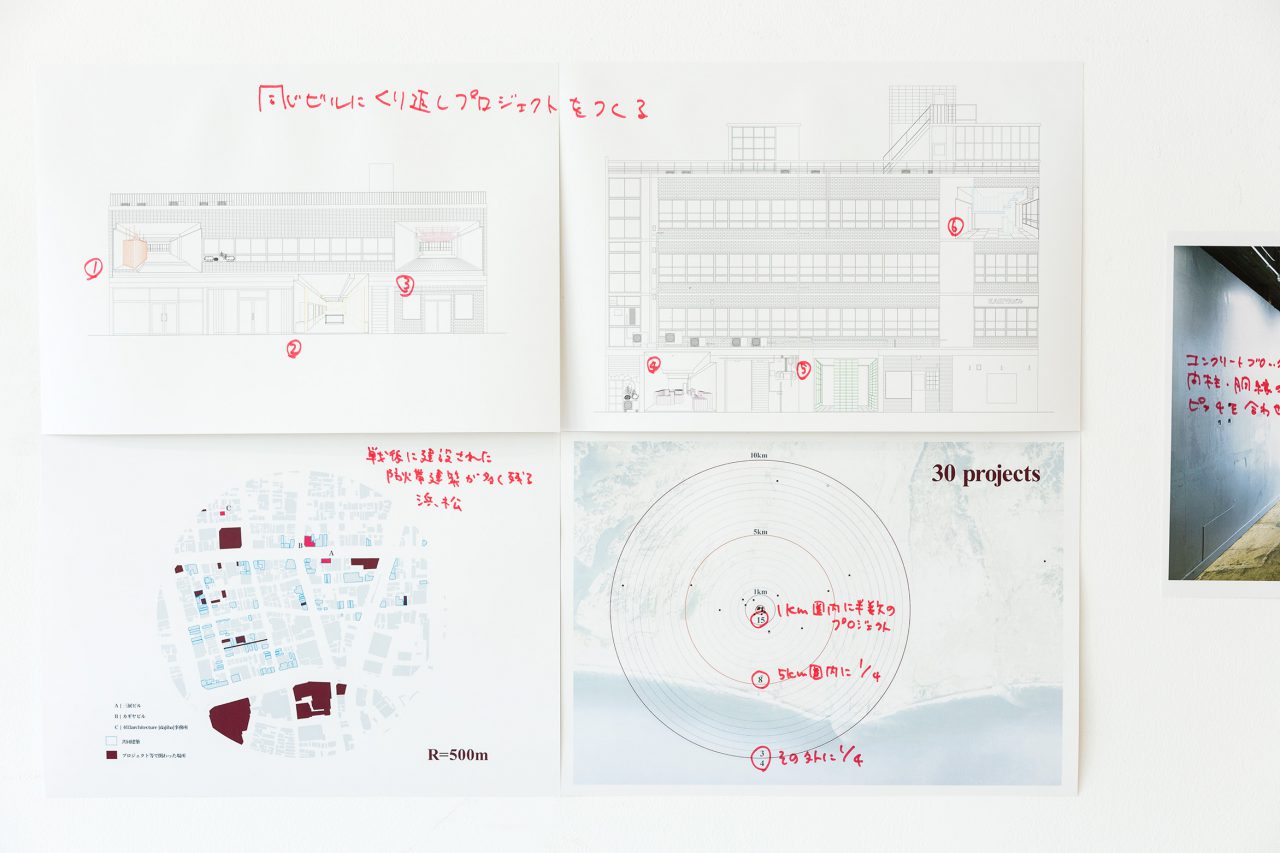

It’s been about five years since we established our office, and we have done approximately 30 projects so far. We have reviewed these projects, including their titles. Particularly in this exhibition, we organized what we call “tags.” We have been using “tags” before the exhibition for categorizing approaches, ideas, shared perspectives etc. which can be applied not only to a single project but also across multiple projects. We re-examined the definition of “tags” because it was rather ambiguous, and then their titles were renamed. They were also integrated or subdivided into appropriate categories. Instead of describing each project in detail, we aimed to exhibit how we perceive projects as a group by showing them according to “tags.”

For example, there is a tag named “Gaps in Customs,” and a renovation project of “The Ceiling of Tomitsuka” (2012) is tagged in this category. Japanese houses are typically built with a large opening and windows in the south, and this particular house was no exception. It was, however, in a residential area and a neighboring house in the south was closely built so that it affected the amount of sunlight coming through the windows. Besides, it was rather difficult to open the window freely without feeling the neighbors’ eyes. Taking these factors into account, we reduced the size of windows by installing a wall and a storage rack in the south side of the house. In the north side of the house, on the other hand, the window area was enlarged by replacing an ordinary flush door with a floor height double sliding window. An entrance with a double sliding door was also in the north side and there was a level difference from the street, which made this part of the house relatively openable. In addition, smaller windows in the south also became openable, which made the house well-ventilated. Therefore, critically evaluating the customs and applying them in different ways can lead to the influence of original customs to be re-examined.

-

The Wall of Zudaji (2011) ©Kenta Hasegawa

In another case, a constructional material used for a storehouse project “The Wall of Zudaji” (2011) was something close to laminated wood; lumbers are glued to each other. What was unique about the laminated wood used in this project is that the lumbers were not completely glued but glued with spaces. Since it was used as a storehouse, we explored the balance of sunlight coming through, just enough for working inside it. That is to say, we created windows directly on the laminated wood. The exterior walls were covered with transparent polycarbonate corrugated panels for making it water resistant. It resembles to a very common shed simply built with a wooden framework and corrugated panels, but the proportion of wood used is exceptionally high. In this project, we tried to perceive the customs such as the laminated wood and a simple shed from a different point of view, with consideration of mechanics, environment, economy and so on. We tried to create “Gaps in Customs” which will provide a connection to a new context. Tags are useful for organizing ideas from different projects.

-

The Ceiling of Tomitsuka (2012) ©Kenta Hasegawa

How do you perceive and design the window as an architect? I understand that you have used elements such as stairs as the main theme of your work in the previous projects.

Hashimoto: As I said earlier, we installed an aluminum sash between the entrance and the room in “The Ceiling of Tomitsuka” project. In another renovation project “The Depth of Yoyogi” (2015), there was a triple sliding steel door at the entrance and we installed an aluminum sash at the back of a doma(earthen-floor)-style room. I may consider an aluminum sash not as a so-called window but as something like an airtight and transparent piece of furniture.

For example, if you build an extension on the other side of a window, the window is not a window anymore but becomes an entrance. An entrance of a room, on the contrary, may become a window. Although it is certainly necessary to take constructional measures including waterproof and insulation treatments, I probably consider the window as a temporary element rather than something absolute for dividing the inside and outside of the house.

You have mainly done renovation works in your career so far, and could you tell us what you think about newly constructed architecture?

Hashimoto: We perceive the architecture in a way that materials come and go from some place to another, and we call it “flow of the material.” From that point of view, it is fundamentally the same whether the architecture is newly constructed, renovated, or even demolished. In the process of constructing buildings as an industry, the construction system has advanced and been divided into clearer categories. However, traditional wooden architecture in Japan used to be much more ambiguous about such categories.

For example, in Ise Jingu Shrine, after the main building of the shrine is demolished for the ceremony of Shikinen Sengu (transfer of a deity to a new shrine building once in a prescribed number of years), the old materials are distributed nationally and become materials for constructing other shrines. This is a rare example, but it used to be a common practice for Japanese architecture to have parts or roof replaced. I see both renovated and newly-built architecture as a continuous phenomenon. At the same time, I’m also fully aware of the construction method which is totally unique to the new buildings, due to contemporary factors including the length of design period and institutional procedures.

Not so many young architects work so close to the local communities, like you. Could you talk about the reason why you are based in Hamamatsu, Shizuoka prefecture?

Hashimoto: Takuma Tsuji, one of our members was from the district. It was about one year after the graduate school when we advanced working positively in Hamamatsu. Since the graduate school, we have already worked as a unit, 403architecture. During the certain period after the graduation, we continued to work for some small activities such as workshops, and exhibition designs. When “Architectural Conference of Hamamatsu” was held in Hamamatsu, we had an opportunity to plan a related workshop. Meanwhile we knew so little about Hamamatsu, but we came to know that shopping districts had turned into “shuttered streets”. As we said “then, shall we study the condition of the vacant rooms?”, we started mapping abandoned houses with the local students at Shizuoka University of Art and Culture. We examined various kind of things, for example, how many vacant rooms there are on the ground floor or upper floor, how their distribution is, what their relation is with years after construction. Since our investigation seemed not to be sufficient, we negotiated with the owners of vacant properties to rent them to us for a certain period. We rented four spaces at the same time, and asked the students to make installations there. At that time, we also organized the workshops to make the installations bringing the available materials from somewhere.

Gradually the owners began to recognize us as the guys working around architecture, and asked “are you working in architecture?” At first, we didn’t have an architecture office established. However, they began to offer us some works. Probably they just had an impression that we were young men good at DIY. It led to the new business. There were surplus of similar kind of vacant single-room apartment remained without tenants even in real estate agent, and we had to do something with them. Vaguely, we felt that in this environment we could deal with such structural problems.

When talking with these owners, they always let us do it for ourselves. Even though I studied architecture at the university, actually I knew so little how the buildings were constructed. It was very attractive for me to dismantle them for myself. By following the opposite process of breaking houses down, I was able to learn how to construct them, I thought. Of course I had a choice to get a practical training at an architectural office. But I started to work in Hamamatsu, thinking that it was an alternative way of working in architecture, to use the stocks already finished, and deal with them.

How many years has it been since you started to work in Hamamatsu?

Hashimoto: It will be 5 years, soon. I think I have settled at the best place, being able to continue working without interruption. In recent years I have received various commissions. Hamamatsu is a good place for marketing tests, because it is located just in between Kanto (Eastern part of Japan) and Kansai (Western part of Japan), and there are some big industrial companies. At the same time, it is a medieval town under a castle. It is also a typical city where both the city center and the suburban area are developed. This makes the result of marketing investigation in Hamamatsu often be applied to another area. In this sense, I think it has a convenient scale for us. In larger cities such as Osaka, Nagoya, and Tokyo, we would have to choose a different approach. Or in the cities with smaller population, the local community may be too strong that there is no substitute for us. That would probably be difficult too.

As you talked, your activities have been mainly based on a local area. What is your ideas in presenting them in more global scales at Venice Biennale?

Hashimoto: Currently we have about 30 projects in progress at the same time. We are doing 15 projects, which is a half, within 1km distance from our office. Since we have worked in the almost same area, we have got the accumulation of the local contexts, and understood that history. If we work in a distance, it will be the same. We see things as an architect built up in Hamamatsu. Each architect has his/her own approach with his point of view. For instance, various architects apprenticed in different places have different perspectives on a city.

When we talk about the regional history in Hamamatsu, it usually means the history after WWII. I am strongly interested in what happened after WWII, although I refer to the story before the war, or traditional days. When we work in Tokyo, we can also consider by focusing on the matters after the war.

In case of Venice, it has a different meaning of “after the war”. The key point is what kind of contexts are behind. Considering what kind of place Venice is, and what kind of industry there is, I thought of glass. Glass is a typical product in Murano islands. Also, it is a traditional material combining unique industry, history, and technology. I think we can make a good use of it. Our experiences in Hamamatsu probably lead us to such an approach.

Could you tell us about the details of your exhibition plan at Venice Biennale?

Hashimoto: The exhibition consists of photos and works built on site. Main theme of Japan pavilion is “en: art of nexus”. Since we belong to the category “en in things”, we will put a focus on things. We are going to install photos of several projects, and show what material we make use of and how. In fact, the word “en” contains vast meanings, and it almost means relationships. To show our approach, I think it can be the simplest way just to show how we deal with it. For this reason, we are considering of making things using the local materials rather than bringing mock-ups made in Japan. What they call “slapping” is, distorted, cracked, failed Venetian glass which can be re-used once it is melted and solidified into blocks. We are going to construct a sort of arch using these blocks like bricks.

It requires sophisticated technology to remake the glass materials, so we prepare the exhibition in collaboration with local furnaces. The glass-making history began at Murano island in Venice. The local artisans have very delicate skills. In such a condition, we want to work on the project by making a new relationship between the traditional technology and the local places. Our project intends to represent the icons of Venice, since we had the strong impression of many channels and many bridges over them in Venice.

What is your favorite window?

Hashimoto: After finishing graduate school, I did some small jobs and saved up money, and traveled Europe for an extended period of time, visiting a lot of architecture. I started from Italy, and travelled to Switzerland, Germany, and France. I travelled down to the south and at the very end of the journey, I went to Unité d’Habitation in Marseille, designed by Le Corbusier. I was totally impressed and overwhelmed by that architecture, only by its exterior design. As you may realize, however, the design of Unité d’Habitation is basically the intensive repetition of windows. Even before I visit there, I knew as a knowledge that the architecture was a complex of restaurant, hotel, kindergarten once standing on the rooftop and so on. I was deeply impressed that such an enormous scale of concept was realized. To put it crudely, the exterior of Unité d’Habitation can be described as a mere repetition of windows, compared to Chapelle Notre-Dame-du-Haut de Ronchamp, Couvent de la Tourette, or Villa Savoye. I just couldn’t tell why Unité d’Habitation was still incredibly impressive.

Then I realized, and to put it crudely again, I have seen an enormous number of apartment buildings in Japan, quite similarly with the repetition of windows. The exterior design of those buildings was not so much different from the design of Unité d’Habitation, but something crucial was completely missing for those apartment buildings. That something is, I feel, strongly related to how I perceive the architecture. I guess it’s nothing to do with the proportion according to the Modulor. Whether it was architectural or not is dependent on what you sense and what you view in the background of the building, I felt.

What is your favorite window?

Hashimoto: After finishing graduate school, I did some small jobs and saved up money, and traveled Europe for an extended period of time, visiting a lot of architecture. I started from Italy, and travelled to Switzerland, Germany, and France. I travelled down to the south and at the very end of the journey, I went to Unité d’Habitation in Marseille, designed by Le Corbusier. I was totally impressed and overwhelmed by that architecture, only by its exterior design. As you may realize, however, the design of Unité d’Habitation is basically the intensive repetition of windows. Even before I visit there, I knew as a knowledge that the architecture was a complex of restaurant, hotel, kindergarten once standing on the rooftop and so on. I was deeply impressed that such an enormous scale of concept was realized. To put it crudely, the exterior of Unité d’Habitation can be described as a mere repetition of windows, compared to Chapelle Notre-Dame-du-Haut de Ronchamp, Couvent de la Tourette, or Villa Savoye. I just couldn’t tell why Unité d’Habitation was still incredibly impressive.

Then I realized, and to put it crudely again, I have seen an enormous number of apartment buildings in Japan, quite similarly with the repetition of windows. The exterior design of those buildings was not so much different from the design of Unité d’Habitation, but something crucial was completely missing for those apartment buildings. That something is, I feel, strongly related to how I perceive the architecture. I guess it’s nothing to do with the proportion according to the Modulor. Whether it was architectural or not is dependent on what you sense and what you view in the background of the building, I felt.

Takeshi Hashimoto

Born in Hyogo prefecture in 1984. Graduated from the Department of Architecture at National Institute of Technology, Akashi College, Japan in 2005. Graduated from the Architecture and Building science at College of Engineering, Yokohama National University in 2008. Finished Y-GSA (Yokohama Graduate School of Architecture) at Yokohama National University in 2010. Established 403architecture [dajiba] in 2011. Honored with the 30th Yoshioka Award in 2014. Part-time lecturer at Meijo University since 2014. Part-time lecturer at University of Tsukuba in 2015.

http://www.403architecture.com/

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Japan Pavilion, The 15th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2016

Steel House

27 May 2016

Japan Pavilion, The 15th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2016

House at Komazawa Park

27 May 2016

Japan Pavilion, The 15th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2016

Boundary Window

27 May 2016

Japan Pavilion, The 15th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2016

Sunny Loggia House

27 May 2016