Chiharu Shiota

The Sense of Daily Life and Smells Soaked into Windows Gives Power to My Work

15 Oct 2019

- Keywords

- Art

- Arts and Culture

- Interviews

Chiharu Shiota is an ever-active Berlin-based artist. In works such as her large-scale installations that tie spaces together with massive amounts of threads, she has used clothes, beds, suitcases, and other familiar materials to create art with deep roots in her own spirituality. Her largest-ever solo exhibition, Shiota Chiharu: The Soul Trembles began in June 2019 at Mori Art Museum, Tokyo. This exhibit includes works that use windows, a core motif in her art. We asked this artist who says she was inspired by Germany after the fall of the Berlin Wall about the meaning of windows in her own work.

Shiota Chiharu: The Soul Trembles, now being held at Mori Art Museum, is your largest-scale exhibition in your approximately 25-year-long career as an artist. Throughout your work, you’ve shown many works that take windows as a motif, such as Inside – Outside (2009/2019), a part of this exhibit. Could you tell us what led you to make this work?

When I moved to work in Berlin in 1998, there was construction being carried out all around the city. The origins of this work came from when I saw a scene of removed windows lined up at a construction site, causing me to wonder if I could make something from it. Though nine years had already passed since the fall of the Berlin Wall at the time, the situation was still chaotic, and there were still many vacant homes in town.

The Berlin Wall divided people from the same country who spoke the same language. It even created walls within people’s hearts as a result. About twenty years earlier, I imagined what people on the east side of the wall must have thought of the people on the west side, and I came to realize that windows are full of people’s history and emotions, every one having its own story.

-

Chiharu Shiota

So your works using windows were first born from the experience of seeing a construction site. I imagine it must have been very difficult to gather this many windows.

For the most part, we only come into contact with windows as part of a building, and we rarely see just windows on their own. But when I saw all of those windows laid out in a courtyard, it made me think that I could catch a glimpse of the memories and lives of the people who lived in the rooms they were once in. That is when I began my days of going around construction sites in order to collect windows.

At that time, I spent morning to night doing nothing but going around construction sites. I think I was at a pace of as many as 20 a day. As I did this, I began to figure out when during the demolition process each site would remove their windows. As they’d begin removing the windows and lining them up at the construction site, I would go to the people working there and ask them if they could give them to me for my art.

Most old windows are disposed of, so they were usually generous in giving them to me, though some people would try to sell them at a high price. I spent half a year doing this, so you might be able to say that I was possessed by windows at that time. The attic atelier I used at the time wasn’t big enough to store the windows I gathered, so I had no choice but to rent a small warehouse in the suburbs of Berlin. As I was also renting a cheap atelier with a courtyard, I found myself penniless all thanks to windows (laughter).

-

Looking out at the streets of Berlin from the opening of a building with a removed window.

View of Construction Site in Berlin, 2004 Photo by Sunhi Mang

Were you gathering windows before you came up with the idea for your work?

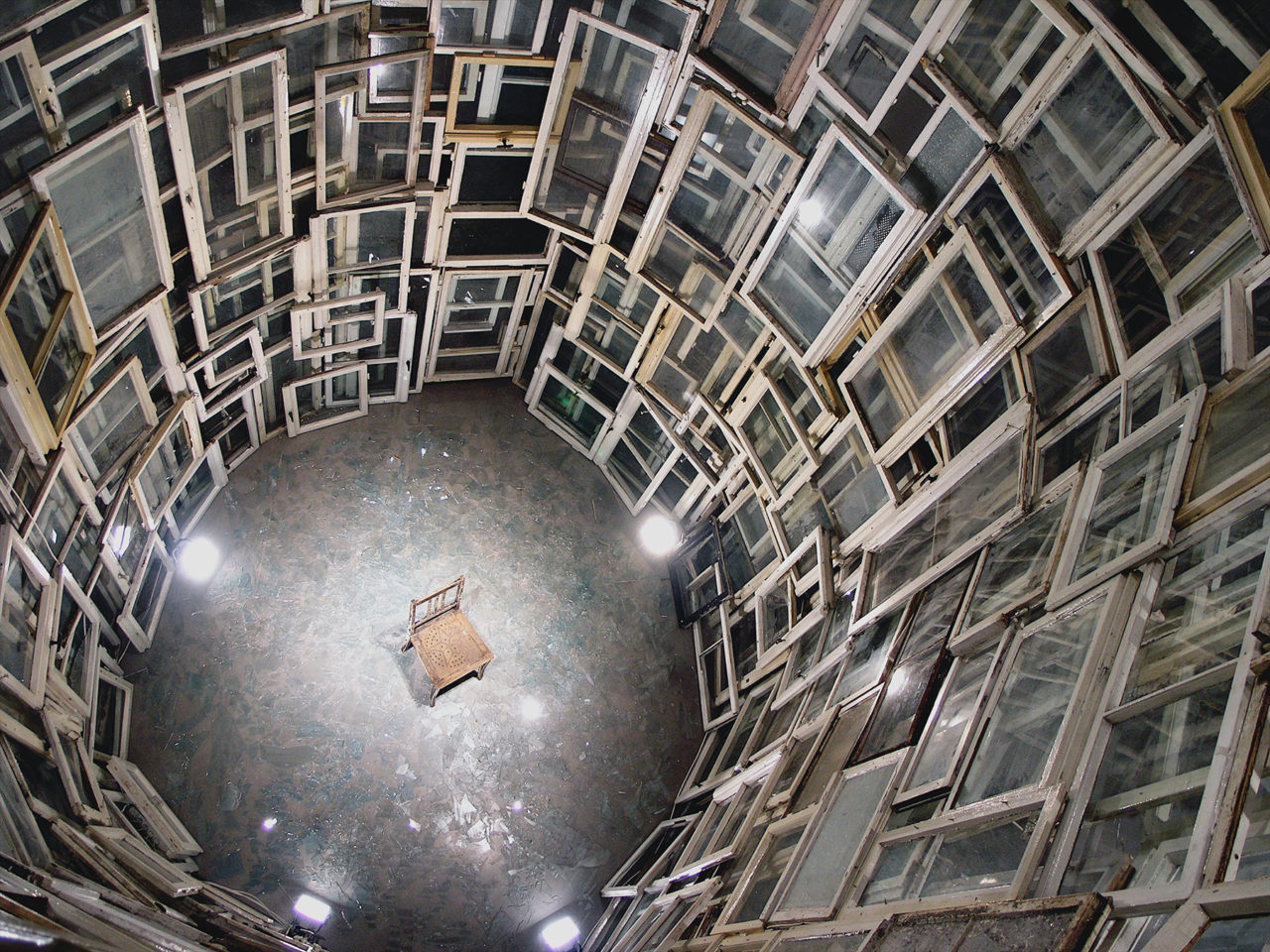

I was. My first work using windows was in made for my 2004 exhibition at the 1st International Biennial of Contemporary Art of Seville. I realized that the 600 windows I had initially gathered to make the work wouldn’t be enough, so I went back to gather more. My next work was His Chair, which I made for a 2005 exhibit at the ARoS Aarhus Art Museum (in Denmark). For this, I put together about 750 windows for an exhibition celebrating 200 years since the birth of Hans Christian Andersen, Fairy Tales Forever—Homage to H.C. Andersen.

For this work, I put the windows together in a cylindrical shape, then placed a single chair in the center of them. Though this chair is an homage to Andersen, it is also a work where you can see the lives, families, and histories of people through windows. When I ran out of windows while making the work, I even made my own frames out of wood. Inside – Outside, which is now being exhibited at Mori Art Museum, also makes some use of window frames I made with screws.

-

Chiharu Shiota His Chair, 2005

Installaiton: old wooden windows, chair

ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum, Aarhus, Denmark

Photo by Sunhi Mang

Copyright JASPAR, Tokyo, 2019 and the artist

© VG BILD-KUNST, Bonn & JASPAR, Tokyo, 2019

G1956

In The Soul Trembles, the following striking phrase is printed on a wall of the hall: “Our first skin is human skin. Clothes make up our second skin. If, then isn’t our third skin made up of our living spaces——the walls, doors, and windows that surround the human body?” It is both so a very unique thought as well as a feeling that I think we all share. What were your thoughts behind these words?

I only started being aware of skin after I began living overseas. For example, humans are very weak creatures within a jungle compared to other animals. We can call the clothes of these humans’ their second skin, and outside of that are living spaces, which we should call a third skin.

Having lived in Berlin for a long time, I sometimes don’t know if I’m “coming back” to Japan or if I’m “going” to Japan. Whichever way I go, neither are paths home at this point. While the idea of skin in the sense that I just brought up is like an existence that acts as a border separating the inside and the outside, going back and forth between Japan and Germany feels like I’m standing in a space that is neither inside nor outside, but in between. This kind of cycle may have also been what caused me to be possessed by windows.

Have you ever felt rootless during your many years living in Berlin?

Whenever I make my art or display it, I’ve had a strong feeling of not belonging to anywhere, and that I’ve been making moves on my own. I think this kind of motivation is also expressed in putting myself in uncertain situations, while in my work it connects to the creation of art that does not rely on strong structures.

-

Inside – Outside (2009/2019), exhibited at Shiota Chiharu: The Soul Trembles at Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 2019

For example, my works that use windows are made up of nothing more than windows, with no structure supporting them. As each window has its own significant weight itself, there is also the physical consideration that a regular iron structure would bend even if I made one, but what’s most important to me is my desire for situations where an object or objects stand on their own even if they may not be stable.

At the opening of The Soul Trembles, you also cleverly said that feelings of uncertainty are what cause you to create works. It seems that your own uncertainties resonate strongly with the appearance of windows.

What is interesting about windows is that they do not stand alone. You must create something strong and sturdy from the ground up in order to stabilize hundreds of windows. Combining them all into a cylinder is what gives the work as a whole a stable structure. This kind of creation involves not only uncertainties, but all of my thoughts and emotions such as doubts and vexations. But, as I said earlier, I did not clearly know at first that I would create in this way. It was something I began to see through the process of collecting windows, as I thought, “Ah, so this is why I wanted to make this work.”

-

Inside – Outside (2009/2019), exhibited at Shiota Chiharu: The Soul Trembles at Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 2019

So the situation of windows lined up at a construction site as well as the chaotic situation after the fall of the Berlin Wall were tied together inside of you and pushed you toward creating work.

I do not immediately give form to my ideas. Instead, I begin creating after thinking about them for a good amount of time. His Chair and Inside – Outside also required a lot of time to think about how they would look after I gathered the windows. The free time I spend planning is very important to me. I do not create many drawings because the rough sketch itself will become a work of art. The time I spend vaguely thinking and not doing anything, in part so as not to destroy my mental image, is very important to me.

Farther Memory (2010), which you created for the Setouchi Triennale, is a work that uses an old community center in Teshima as its location. I think this area would have been a different scene for you than Berlin, but what did you think about it?

Just as I collected windows in Berlin, I gathered over 400 doors, windows, and screens from seven islands in the Seto Inland Sea. They were all once used in people’s daily lives. I put them together to create a tunnel-shaped work. I created Farther Memory in a place called Ko, and at the time a child had just been born in that hamlet for the first time in about sixteen years. The town is connected to rice paddies by way of this tunnel, while you can see the home where that child was born in the opposite, town-facing direction.

A wedding ceremony was held using this work in 2016. When the village mayor told a member of the art festival staff about a wedding that was previously held in this community center, they too said they would like to hold their ceremony here, using the tunnel as a wedding aisle. While I unfortunately was not able to attend, I could see in the pictures I later received the villagers giving the couple their blessings, making this a work that has left a deep impression on me.

-

Chiharu Shiota Farther Memory, 2010

Installation: Old wooden windows, wooden fittings

Setouchi International Art Festival:

100-Day Art and Sea Adventure, Teshima, Japan

Photo by Sunhi Mang

Copyright JASPAR, Tokyo, 2019 and the artist

© VG BILD-KUNST, Bonn & JASPAR, Tokyo, 2019

G1956

Regarding the relationship between art and people, you have also been involved in art direction for many theatrical productions, such as Tattoo (Written by Dea Loher, Directed by Toshiki Okada). How do you feel about the relationship between art and people?

In contrast to Berlin, where I went around collecting windows on my own, in Teshima I needed the help of many people to create my work. When I was unsure of how to act in the village, members of the art festival staff gave me advice such as, “Always make sure to greet the villagers,” and “If a villager shows kindness to you, return your feelings with gratitude in a form other than money.”

The village had no hardware store, and I needed to communicate with others just to borrow so much as a stepladder. Even the villagers who peeked through their curtains to see what I was doing at first eventually began to help me, and I was able to complete the work. So, what happened as a result?

Surprisingly enough, once the art festival began and I left the island, the old men and women apparently would explain the work to visitors. I think the fact that it is created using these windows, materials that are very close to the people of the island, plays a big role in this. I doubt they would have done this had I created a sculpture in my atelier, carried it to the island, left it there, and returned.

When I visited Teshima three years later, I was met with a different village. Everyone there was lively and smiling. The fact I was able to create a connection so strong that someone would hold a wedding ceremony in my work is an experience more valuable than anything else.

-

Chiharu Shiota

As we reach ten years since the first showing of Inside – Outside, we also reach thirty years since the fall of the Berlin Wall. Please tell us your thoughts about displaying this work once more.

While Inside – Outside is being held as part of the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa’s collection, I too saw it for the first time in a while and appreciated once more the weight that windows have. This is because windows are created as a result of someone seeking light.

From August to February in Berlin, the heavy sky is full of clouds day after day. Light coming from windows during such weather must provide people with mental stability. There is a trend in recent buildings to make windows larger, and even in renovated buildings we see large windows that allow for lots of sunlight to come in.

The windows that I use are not brand-new ones prepared for the exhibition, but are windows actually once used by the people living in East Berlin. They exude a kind of sense of daily life and a smell that must give the work some kind of power. Through this work, I myself had a strong experience of how empty a structure without windows is. I think the presence of windows alone can give a building or the people who live inside it vitality.

Shiota Chiharu: The Soul Trembles

Venue: Mori Art Museum

Exhibition Period: June 20 (Thu), 2019 to October 27 (Sun), 2019

http://www.mori.art.museum/en

Chiharu Shiota

Born in Osaka in 1972, Chiharu Shiota traveled to Germany in 1996 after graduating from Kyoto Seika University in Oil Painting. She then enrolled at the University of Fine Arts Hamburg, the Braunschweig University of Art, and the Berlin University of the Arts, and studied under Marina Abramović and Rebecca Horn. She has made Berlin her base for creative work since 1998.

In works such as her large-scale installations that tie spaces together with massive amounts of threads, she has used clothes, beds, suitcases, windows, and other familiar materials to create her art. Her Memory of Skin, exhibited at the Yokohama Triennale in 2001, was widely talked about, leading to exhibitions of her work being held in many museums inside and outside Japan.

She was the Japanese representative artist at the 56th Venice Biennale International Art Exhibition held in 2015. From June 20 to October 27 of this year, she holds her largest ever solo exhibition, Shiota Chiharu: The Soul Trembles at Mori Art Museum, Tokyo. Her written work includes Shiota Chiharu / Kokoro ga katachi ni naru toki (Shinjuku Shobo, 2009).