In New York: Windows and Looks

12 Jul 2018

- Keywords

- Art

- Interviews

Since traveling to New York in the 1970s, artist Masao Gozu has spent over 40 years unveiling work that takes the window as its theme. His Bowery Street (Day ⇔ Night) series that captures New York’s immigrants from a fixed point won him the 10th Ina Nobuo Award and the 1990 Le Mois de la Photo special jury prize. Following this, he worked as a carpenter while beginning to create sculptures that involved taking actual windows out of buildings being demolished and reconstructing them elsewhere. He now works out of his studio in the mountains of Pond Eddy, located in the outskirts of New York, conducting energetic activities such as cutting bricks out of rocks to create gigantic window sculptures.

We spoke to Mr. Gozu during his solo exhibition at the Azumino Municipal Museum of Modern Art about why he continues to create window-themed works and about his creation methods.

The first work you ever showed was your In New York series that depicted people looking out from windows in New York. What made you create this series of works after traveling to the United States in your 20s?

Masao Gozu (hereinafter referred to as Gozu): I first went to an art school in New York, and from there I began drawing. There just so happened to be immigrants where I lived, and I began photographing them because of the empathy I felt for them. That’s why I’m a self-taught photographer.

I may not actually have that much interest in what you would call art. I felt like I was in some sort of in-between space when I was in New York. I think there was a sense of distance between myself and what was around me because I was in another country, and I was interested how all of these things affected me. In a way, windows create a sense of distance between you and a subject, and so that may be why I started photographing windows.

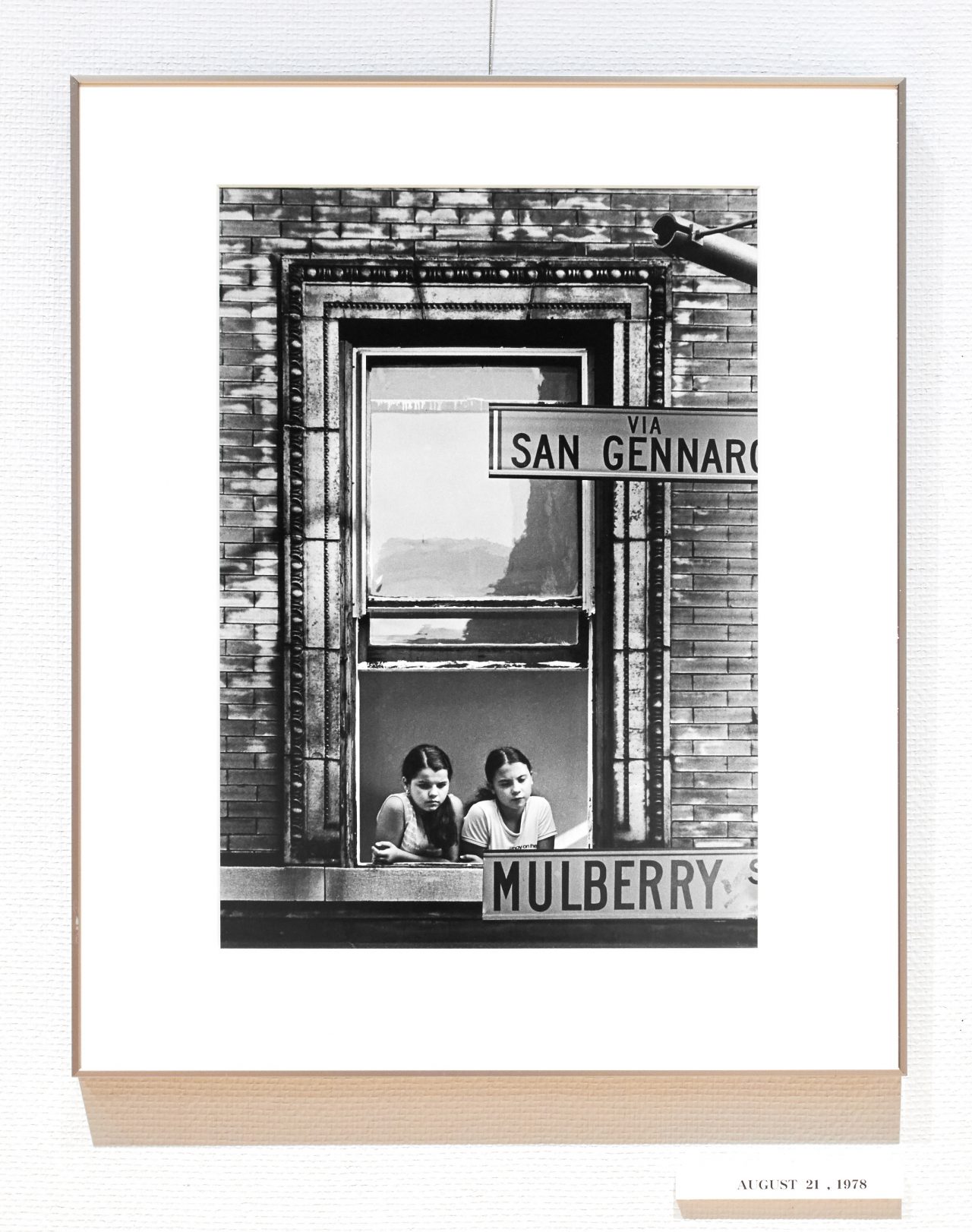

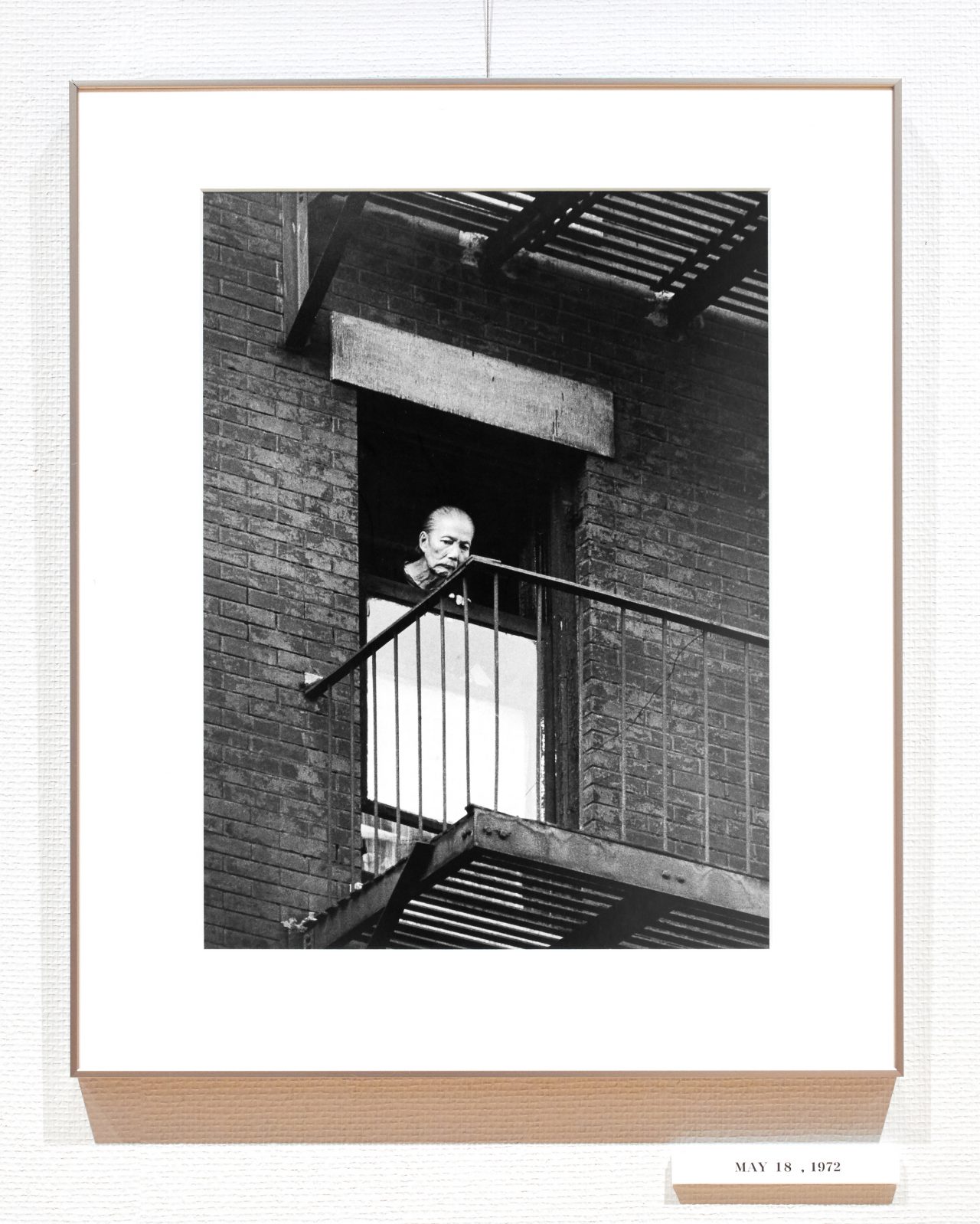

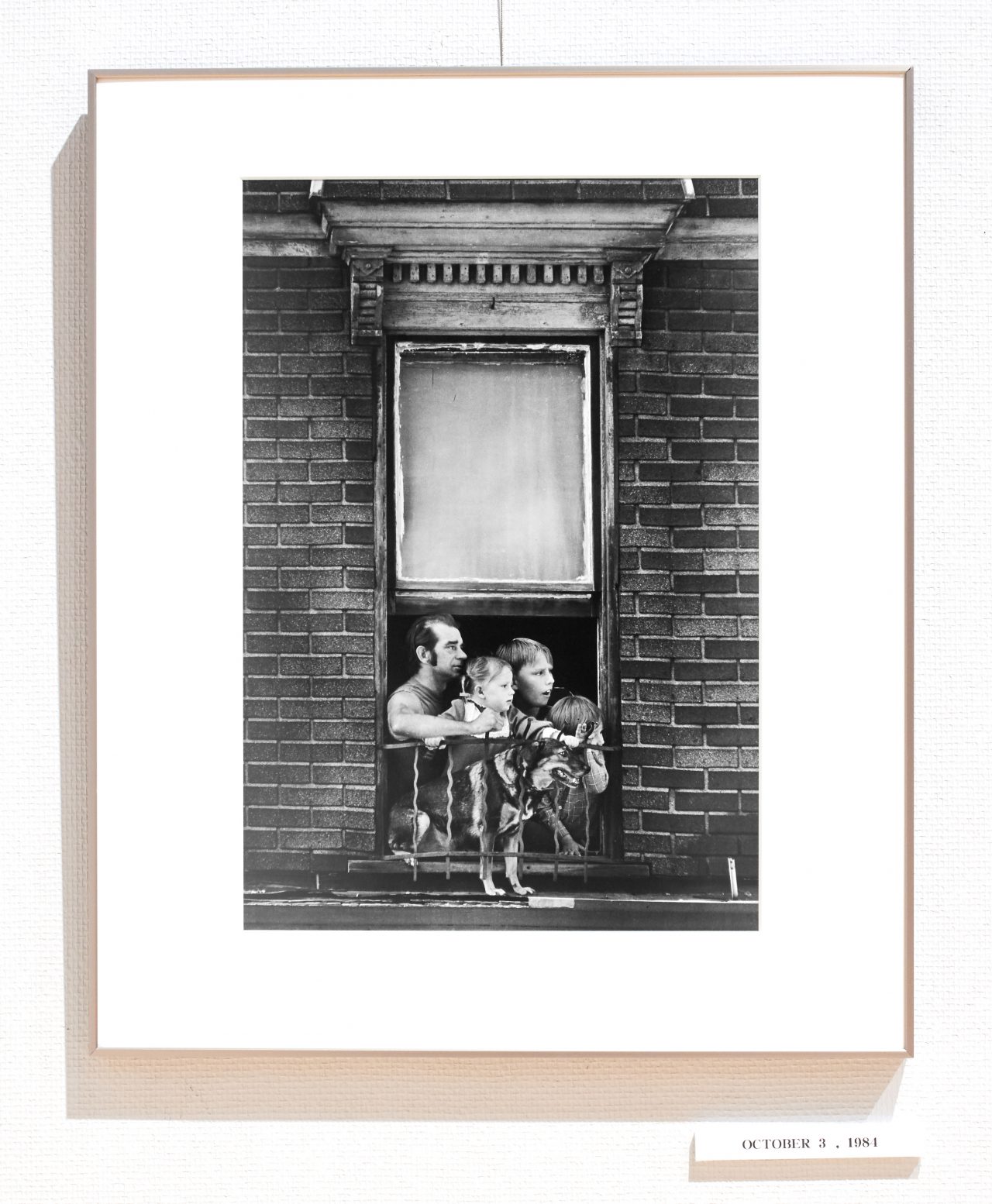

It was lines of sight, or rather, eyes that made me interested in this kind of visual relationship. When you get down to it, eyes are like a window to the building that is one’s body. From there, I started to constantly take pictures of windows. This is my favorite work, and I feel like it’s where I started from. His eyes are sharp. You can say that photographs are a type of eye, can you not?

Were these taken as you walked the streets?

Gozu: Yes, as I was walking. I had my camera and my tripod with me, and I basically took a photo when someone looked out their window. It didn’t go too well because I was a self-taught photographer, and most everything I did then ended in failure.

These are places where many immigrants live, even by New York’s standards.

Gozu: That’s correct. It’s where I lived, too. There were many Latino individuals looking outside the windows. Japanese people don’t look out of their windows as much as them.

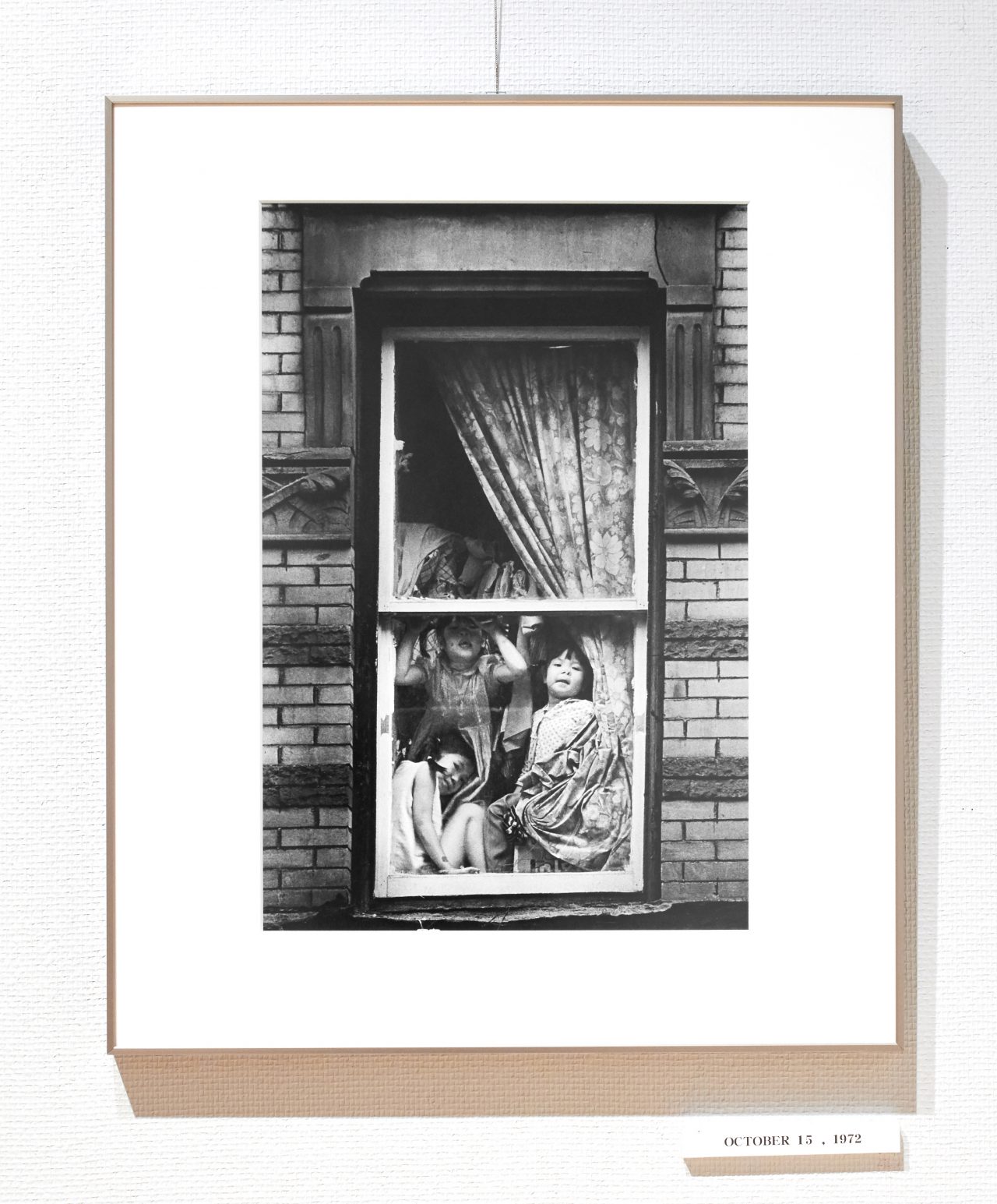

There are many Asian people as well.

Gozu: Yes, the fact that they were Asian like me put me at ease, and so I’ve taken a lot of photos of them. Maybe you could say that I’m reflected in these photos.

The immigrants that lived in this area really would look out their windows for so long. They were always looking outside, with nothing else to do. That’s why some people appear again and again. I was always taking pictures of people like that, and I think that they were ultimately the people closest to me. These windows were mirrors that showed my own reflection.

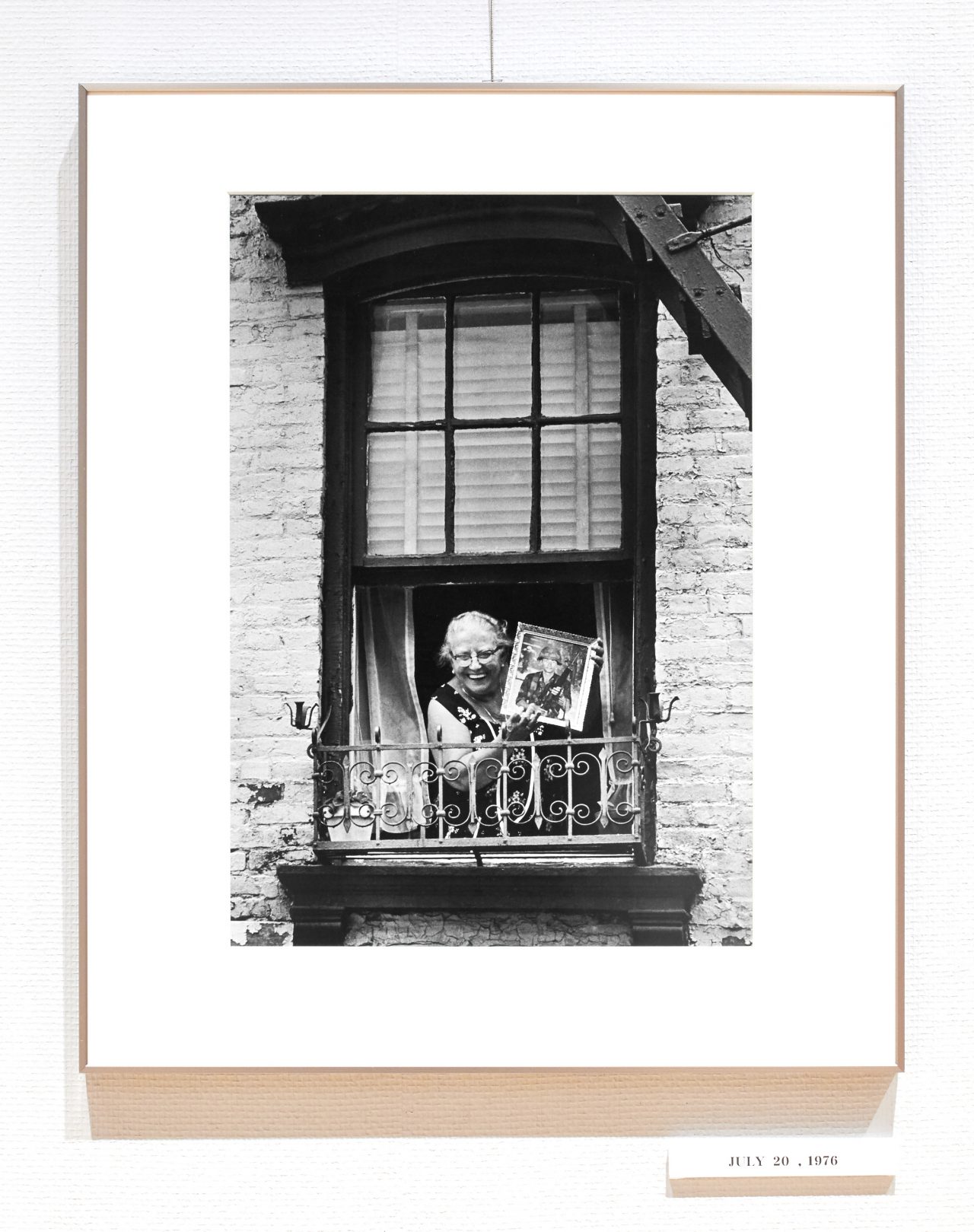

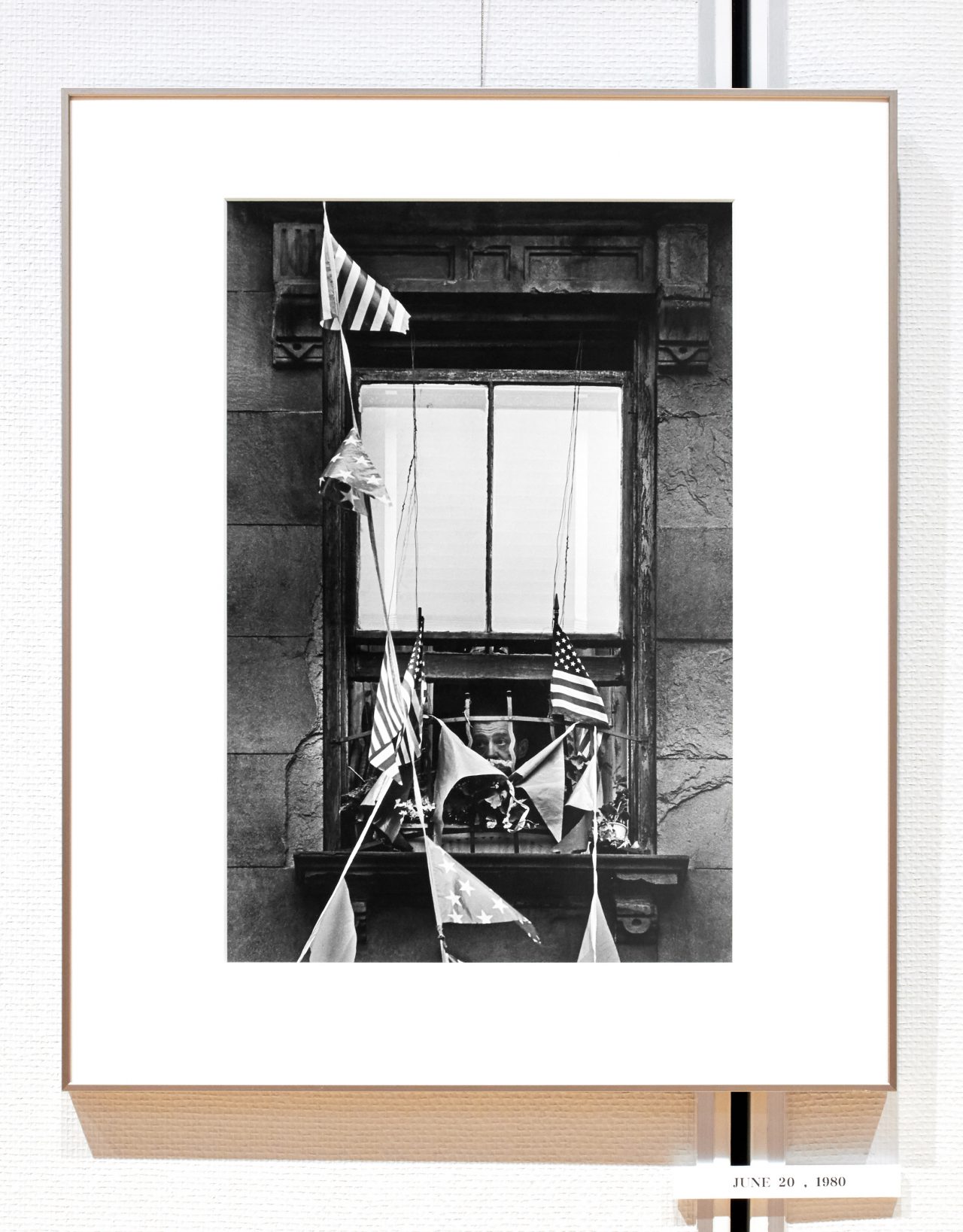

This is a photo of someone watching a New York parade where people march through the streets with their god or something strapped to their back. She’s Italian, and she’s showing this god a photograph of her son who died in the Vietnam War.

This one’s the same. When there are a lot of people in a photo, it’s usually because they’re watching a parade.

Did you ever actually speak to them?

Gozu: I didn’t. It’s not as though this is wildlife photography, but I did want to take pictures of them in a natural state, and so I shot these without their knowledge.

Is there a reason you’ve always shot in New York?

Gozu: Really, I didn’t have much of a choice. I happened to go to New York, and soon that was the only place I could be. I lived around the Lower East Side, and so I took photographs of the area. I was in a very poor area on a road called Bowery Street. It used to be a good place, but it was at its most dangerous period when I was taking photos of it. It’s gotten nice again, with a lot of galleries opening up on it. New York keeps on changing.

There are so many windows that one might wonder if it could act as an archive of New York’s windows. Is there something special about the windows of New York?

Gozu: I think that European artisans created them at first, which is why I think they have an architectural style.

What was the approximate period of time over which you took these?

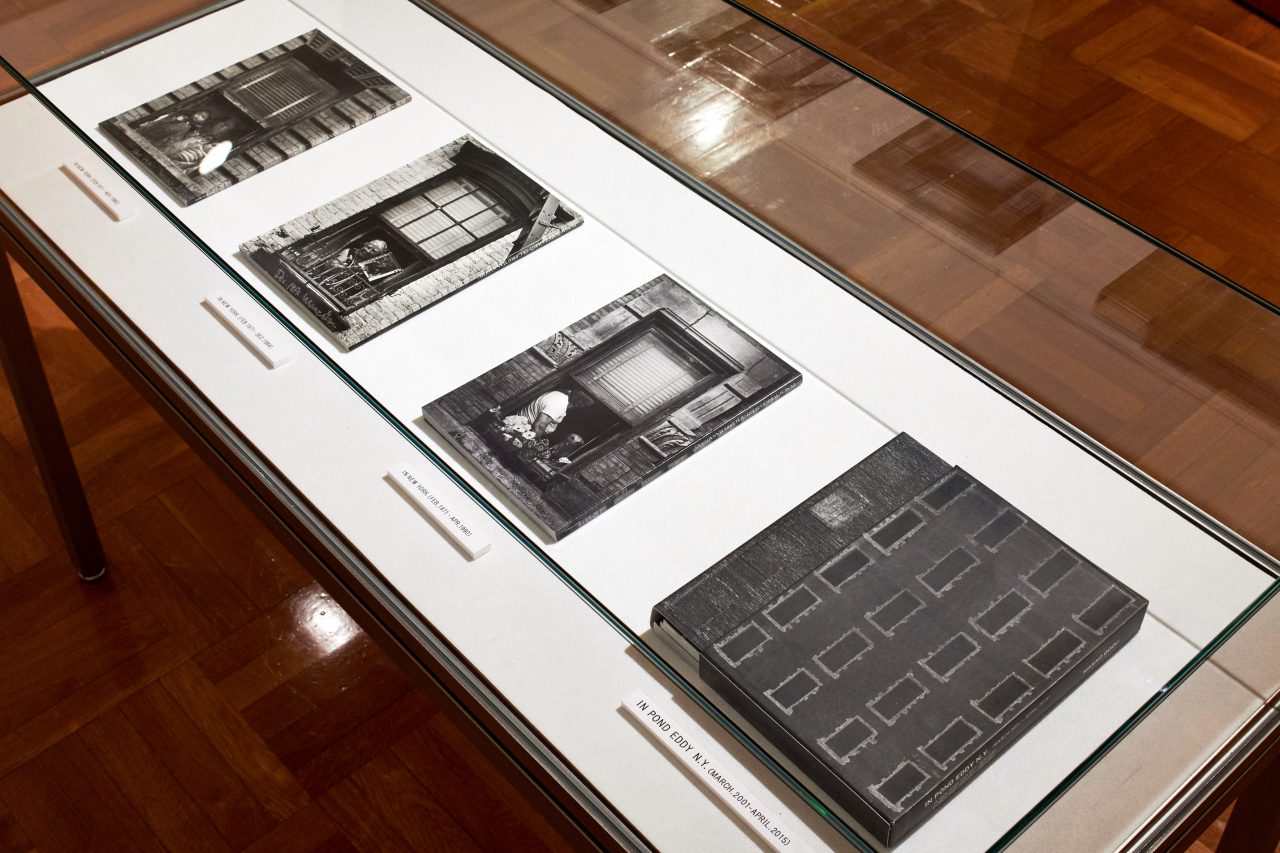

Gozu: I took them over a fairly longer period. I want to say it took a four-or-so year period to take the Harry’s Bar series after this. I kept on taking pictures and saving them, and then I made a book of them. I kept adding to what I made at first, and ultimately I collected them in three volumes.

You self-published them.

Gozu: That’s correct, all of them. Books are a form of expression, after all. In America, there’s a genre of art known as “book art,” which are essentially books created by artists.

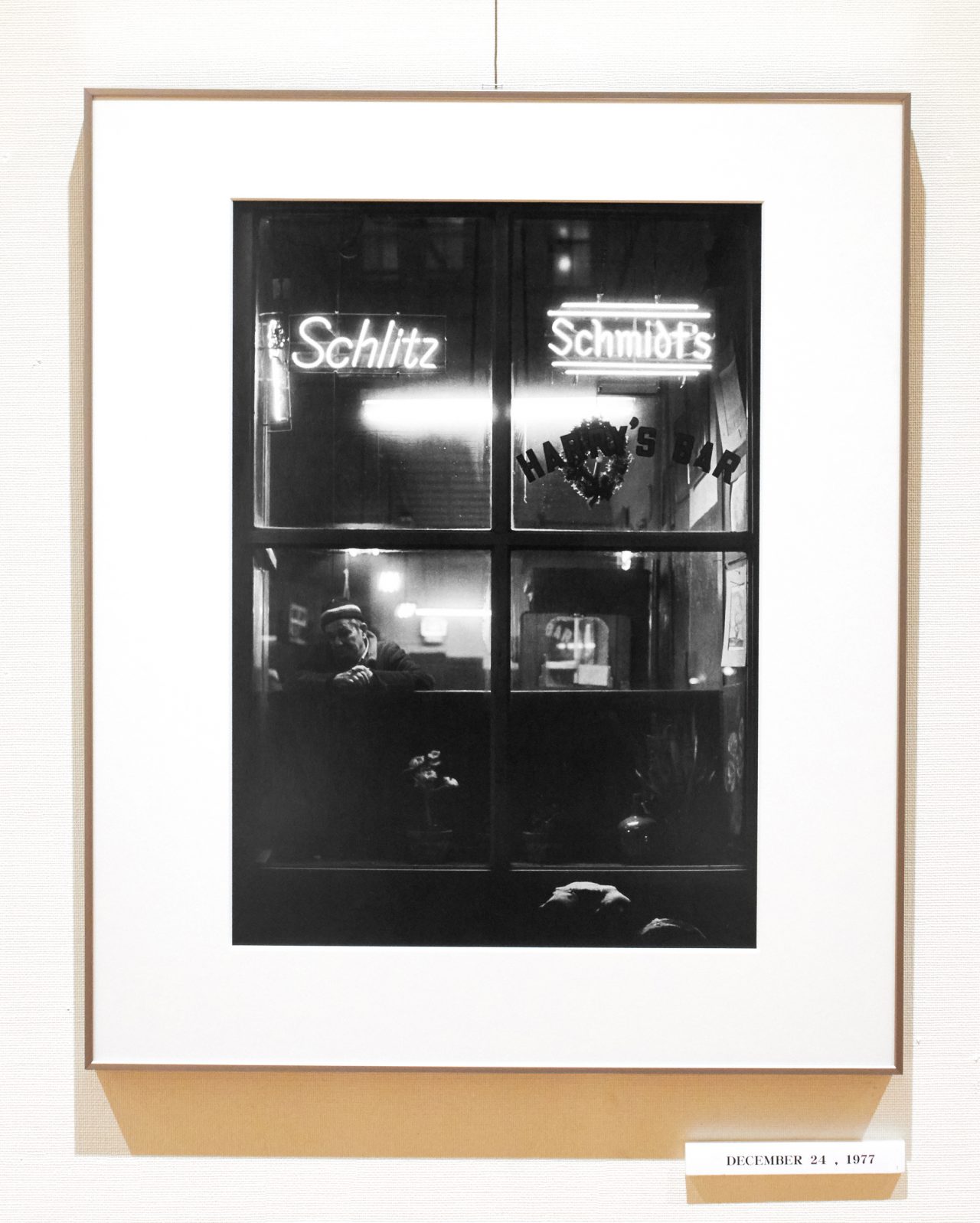

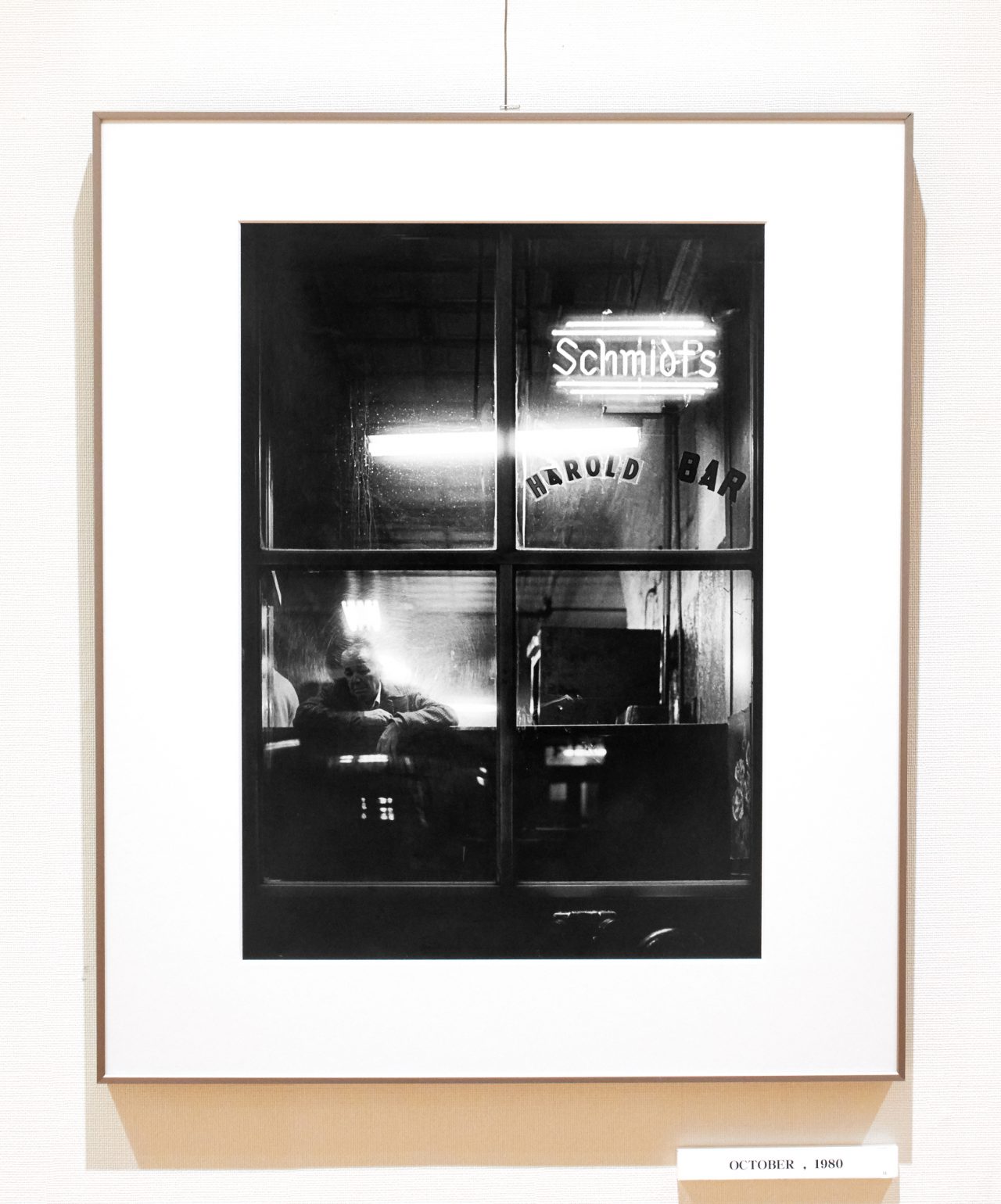

Next, you began to work on a series of fixed point photography of Harry’s Bar, a small bar in New York.

Gozu: It got started while I was putting together the previously mentioned In New York series and happened to take a photo of this place, Harry’s Bar.

It originally takes its name from a fairly famous and fancy bar in Europe where Hemingway often drank. It even appears in novels. But a lot of poorer people went to this Harry’s Bar in New York at the time, and I started taking photos there.

It’s quite the contrast to the original, showy Harry’s Bar in Europe.

Gozu: The plant inside this show window gets bigger and bigger before withering.

Around this time, the name of the bar also changes from Harry’s Bar to Harold Bar. I’m interested in the way that time passes like this. You also see the same people appear again and again. I guess just about all they had to do was go to this bar.

This entire series is taken from the same fixed point.

Gozu: It wasn’t really out of necessity. I happened to not have anything to do, so I’d stopped my car in front of this store and was reading a book. I could always park my car in front of this store, making it easy to shoot.

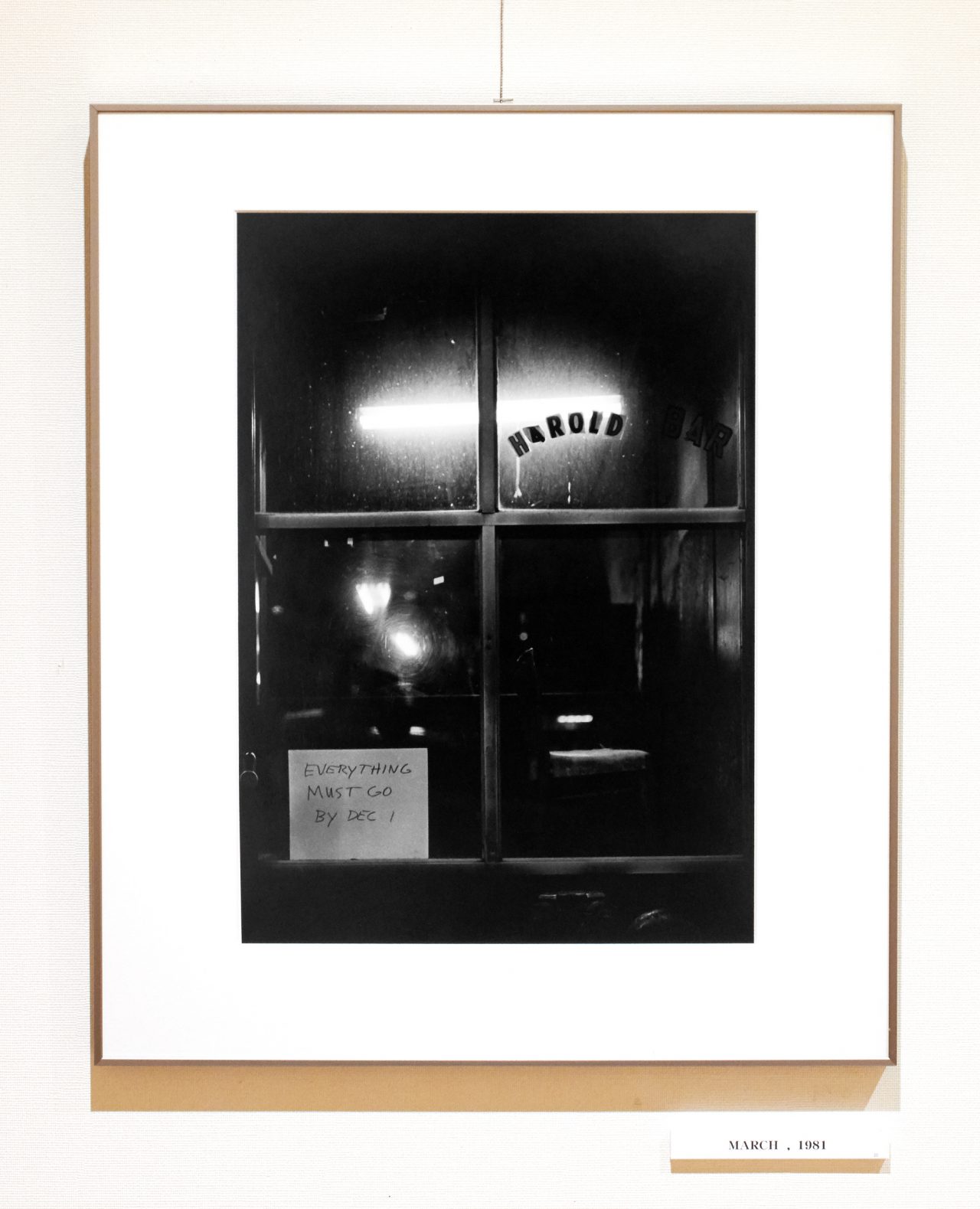

And the store ended up closing during your many years of photography. While it may not have been your intention, you were seeing its history.

Gozu: Yes, though that can only be said in retrospect. This last photo shows a sign saying the store is going to close and that they’re selling everything, “Everything must go.”

Then when I was going to do an exhibition, I thought that if I was going to display these photos, I might as well buy the entire window to show as well. It did say they were selling “everything,” so I thought I’d buy the window itself. The owner was from Florida and so I sent him a letter, but he never replied. He probably thought there was something a little messed up with my head since I was saying I wanted to buy his window (laughter).

It was because of that earlier window at Harry’s Bar that you began creating a series of sculptures that involved actually cutting the windows out of structures.

Gozu: Yes, I wanted to bring windows as actual objects. That’s when I started stripping windows out of demolished buildings. I’d write out instructions on how to build them and then recreate them exactly as they were in a separate location as a piece of work. At first, I was putting them together in my apartment, but they were a little heavy and my floor started to sink, which is why I rented a cellar room and did it there.

here are some words by photography critic Mr. Kotaro Iizawa in the afterword to the photograph collection we spoke about earlier. He says that he felt a strangely calming feeling when surrounded by these excised windows in your studio, and I found that interesting.

Gozu: Yes, as I said, after that I rented a cellar room to work out of because my apartment floor began to sink. It was very cheap. When he came to visit me, I let him stay there. I think he slept there with those windows for about a week (laughter).

Did you create these all on your own, from the act of cutting out the windows to reconstructing them?

Gozu: Yes. I didn’t have the money to hire anyone. I also felt like I had to have this fire escape attached to the windows. They’re a symbol of New York.

Didn’t you run into any problems when cutting windows out of buildings?

Gozu: The people who demolish these kinds of buildings are very rough individuals. I told one, “I’ll give you a hundred dollars if you can get me this fire escape,” and he said, “Okay, I’ll get it for you.” We went to the second or third floor of a building in the Bronx surrounded by other abandoned buildings, and when I told him, “I want this fire escape,” I heard a bang from behind me. When I turned around, there was a gun in my face. I didn’t want to go outside for about a week after that.

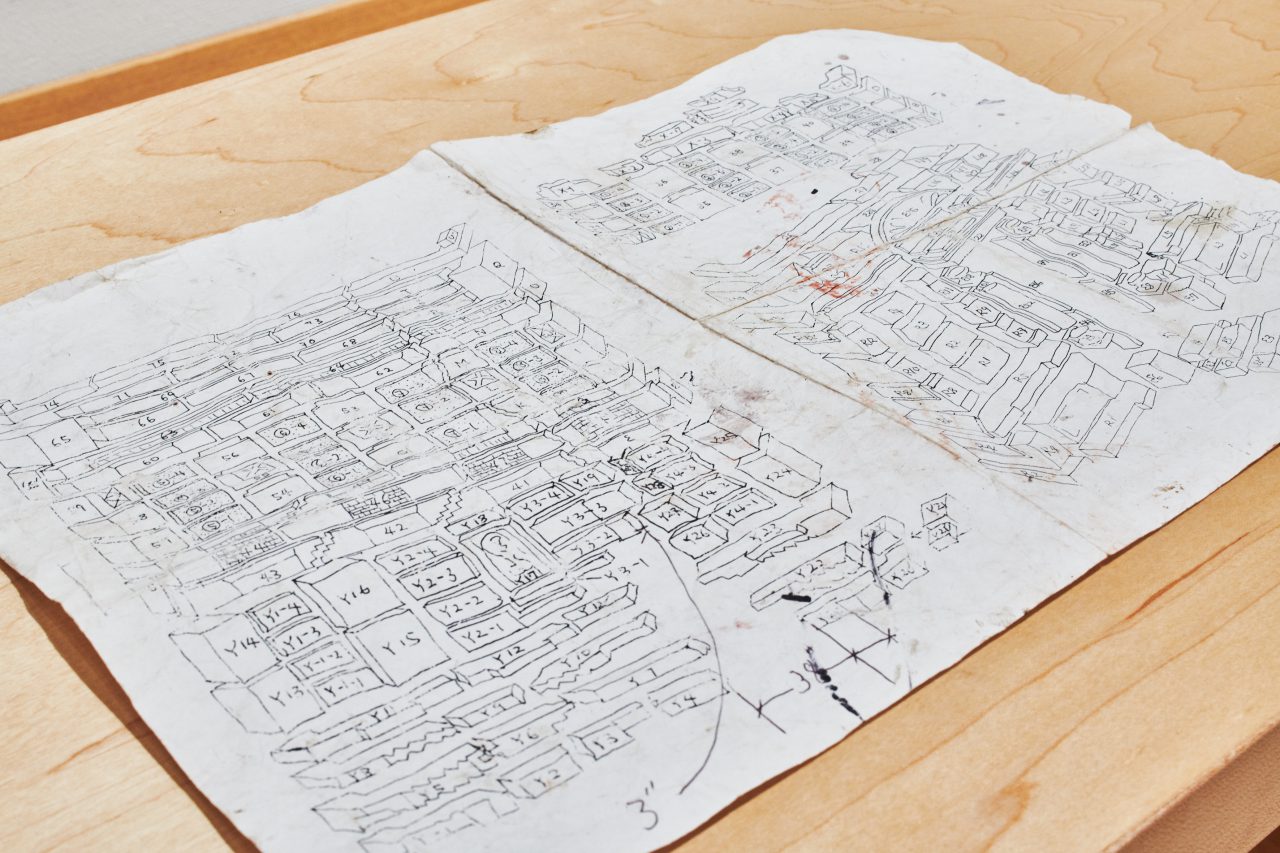

How does one reconstruct windows this big?

Gozu: You put it together gradually from the ground up. Once there’s a section that’s about as heavy as I can lift, I put the thinnest piece of vinyl I can find on top of it, then go back to putting it together. Once it’s all done, I draw a diagram. That way I can build it again next time. Of course, these are pretty sloppy diagrams since I’m only making them for myself.

I had the opportunity to see your handwritten assembly diagrams. They’re incredibly meticulous.

Gozu: All the parts are there and numbered, and that’s the order in which I pick them up. I’m entirely self-taught and come up with how to do this on the spot.

Did you come up with this method on your own?

Gozu: I wasn’t able to live off of photography alone, so at one point I was working as a carpenter. That’s where I learned some of how this is done.

I actually made this to be three stories high so that it would fit perfectly in a gallery, but it ended up being higher than the roof when I tried measuring it. That’s when I hastily made it so that it could be split in two.

How did you transport it?

Gozu: I transported it in a container. I brought about five windows that were even bigger from America when I held an exhibition at the Mitsukoshi department store in the past. The one time I transported them on an airplane was when I brought them to the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, but I returned them by ship.

Rents got higher in the Lower East Side area since then, so I moved to a studio that’s still in New York, but near the mountains. That’s where I began making windows out of stone. Stones with moss and thorns on them. Moss is like a symbol of the passage of time. I cut out stones like this that were near my studio, made them into blocks, then piled them on top of one another to make a window.

-

Gozu’s studio in Pond Eddie, located in the outskirts of New York

It’s very precise work.

Gozu: It’s the same with photography, but I suppose I like the simple act of piling things up. At this period in my life, I was just blindly creating new windows. When I first started taking photos, windows were a kind of mirror to me. But from there, they eventually became something like a stage. Then as I began to create windows, the distance I felt between myself and them started to disappear. Maybe you could say that in the end, I ended up becoming a window myself.

You’re building these windows anew, but at the same time, there’s a large amount of time inside of that window. Do you not have any interest in new windows?

Gozu: No. Making a window cuts out a period in time for me. I think there’s something about the act that shares a concept in common with photography.

Azumino Municipal Museum of Modern Art Special Summer Exhibition: Masao Gozu

Date: April 28, 2018 (Sat) – June 3 (Sun)

Closed May 7 (Mon), 14 (Mon), 21 (Mon), and 28 (Mon). *Open April 30 (Mon)

Admission: Adults ¥800 (¥700), High School Students ¥600 (500), Junior High School and Younger free / Prices in () are for group admission.

Hours: 9 AM – 5 PM (Entry until 4:30 PM)

http://azumino-artline.net/toyoshina/2018/03/post-355.php

Masao Gozu

Born in Hakuba, Nagano in 1946. After graduating from Hotaka High School (now Hotaka Commercial High School), he studied at the Toyo Institute of Art and Design. Traveled to the United States in 1971, and attended the Brooklyn Museum Art School until 1973. Gozu continues to base his activities out of New York. Gozu has exhibited photographs and installations with windows as their theme, covering individuals such as those who loiter around downtown windows. He has held many solo and group exhibitions in locations both inside and outside of Japan such as the OK Harris Works of Art (New York) and the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography.