Series Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

A Conversation with Mario Botta

17 Nov 2020

Mario Botta, a master architect born in Ticino in the south of Switzerland, still lives and works in the area, practicing architectural design.

In this, the second in a series of conversations with Swiss architects by the Chair of Architectural Behaviorology (ETH Zurich), Botta talks about windows, homes, and the city while looking back on a body of work that spans from his early residential projects in Ticino to the Watari-um Museum in Tokyo.

Chair of Architectural Behaviorology (CAB): Since this interview will be shared with a Japanese audience we thought it could be interesting to begin with your single-family houses. Like many Japanese architects, you have used these small-scale commissions as a ʻlaboratory for experimentation’, a testing ground to develop new ideas. Perhaps we could begin by discussing what the element of the window means to you in the context of the domestic space.

Mario Botta (MB): I’d have to first begin by defining the house. Still today, the house is an element of protection, the shelter par excellence. When we’re tired, we still say “I’m tired, I’m going home”. I believe that the idea of the house as the ultimate refuge remains embedded in our subconscious. It’s not about square meters or the richness of materials. It’s the place we go to recharge and find the energy for the next day: a moment of pause within the rush of daily life.

In archetypal terms, the house is the sheltering cave in the mountainside, and the window inside this house is the great void opening up toward the valley—a projection toward the outside world. Even if they’re expressed in different ways, I would like these archetypal forms to persist in today’s culture as well.

-

Single-family house, Ligornetto, Switzerland, 1975-1976 : © Antonio Martinelli

CAB: We’ve been looking at your monographic issue of A+U published in 1986, which gathers all your single-family house projects up to that date. A recurring feature seems to be the idea of having large openings in the volumes which relate to the scale of the landscape and which are then articulated in smaller scale windows connecting to the domestic sphere—often these small windows in turn become fireplaces or skylights linked to the staircase…

MB: Yes. As I said, the house is a shelter, but it also involves what I call the ʻliving rights’ that civilization offers and that the architect can provide for. Rights, for example, regarding the land on which the house sits. From my point of view, the land is not to be inhabited in a literal sense, but should be considered as a space of transition between the outside world and the domestic interior.

-

Single-family house, Ligornetto, Switzerland, 1975-1976 : © Alo Zanetta

So, in all the houses I make there is always this first microclimate of transition at ground level, which establishes a physical connection with the terrain. The living quarters are located on the floor above. Here, the relationship with the surrounding environment is visual, rather than tactile; if you want to go into the garden then you have to go down. The living space offers you the panorama of the city or the external landscape. Above that, there is one last level for the night, a more intimate one that mostly responds to the idea of a relationship with the cosmos—the sky, the stars and the moon—through a skylight that brings these elements into the house.

So, the exercise I’ve been carrying out with these houses is to think about this condition of the house as shelter, its relationship with the territory and the terrain, which is not directly habitable, but has the instrument of the garden at ground level. Then there is the first floor as a gaze onto the habitat, with the second floor as a more intimate gaze toward the sky.

CAB: It is interesting that you have this very clear sequence of levels and yet at the same time the large openings in the volumes are able to establish a connection between them, introducing a sense of verticality. In the above-mentioned issue of A+U there is an essay by Takamitsu Azuma in which he describes how he could relate this sense of verticality in your Single-Family House at Riva San Vitale to his own project for the Tower House in Tokyo.

MB: In the case of the Single-Family House at Riva San Vitale, what I have just described is a bit more exaggerated, because there you have the possibility of experiencing the volume as a whole. Even when you’re entering from the bridge you’re in the void, and this allows you to experience the lower part: you can sense the lake and the church on the other side. The house is an instrument for reading the landscape.

-

Single-family house, Riva San Vitale, Switzerland, 1971-1973 : © Alo Zanetta

-

Single-family house, Riva San Vitale, Switzerland, 1971-1973 : © Antonio Martinelli

CAB: How did you begin to think about this idea of verticality? Is it connected with any experience in your training?

MB: It emerged little by little. It was while I was working on these houses—all of them inexpensive commissions for friends or artists—that I discovered the values I call ʻliving rights’, which are not about the floor area. A house that offers thousands of square meters is quite unremarkable to me: I prefer a house that can offer me different emotions while I’m moving through it. That said, if I could live in the Pantheon I would, because it offers not just a microclimate but also a relationship with the sky.

CAB: And how did your clients react to these kinds of spatial proposals? Were they expecting more conventional horizontal arrangements?

MB: Our traditional old houses already had this kind of spatial richness with the loggia and the attic, for example. These arrangements already exist in the vernacular structures of our village, so there has never been any difficulty with the clients. Designing houses has been a precious experience, truly an apprenticeship. As you mentioned before, it has been a ʻlaboratory for experimentation’ through which I’ve been able to develop other themes, such as the church, the museum and the theater.

-

Single-family house, Vacallo, Switzerland, 1986-1988 : © Pino Musi

CAB: So how would you describe the relationship with the client? Is there an active role for them in the design process?

MB: Yes, but we should not steal the client’s consent. I believe it’s better to let the client dream as well. While I’m not going to ask the client how to do things I’m very interested in their reactions as well. I once had a client who wanted to have the bathroom fixtures black and I couldn’t understand why, since we were already cutting costs everywhere else in the project. But he was right. He was a tonal painter and white would have been obsessive for him.

So, you have to understand the spirit of the client as well. Personally, I’ve never had any difficulty with clients—the difficulty has been more in finding clients sometimes. But once a relationship is established and there is a site the project begins. The client is fundamental, because they’re the one who chooses the site. It’s the client who chooses me, not the other way around.

CAB: How do the houses relate to their surroundings? The large openings in the volumes often become like loggias, which seem to introduce a sense of urbanity into the mostly suburban context…

MB: The house is never isolated. The house is a way to live with others, even if they’re far away. A house is a place that belongs to a community, a history, a memory, a culture. The house connects us and tells us we should take care of the forest, the lake, the land, the fields, and even of our neighbor. Our neighbor is a friend, someone that lives like we do.

Yet, the world often goes in a different direction and we see rows of identical houses which are often perceived as places you go to isolate yourself. But the house is our means of living in a community, this is what our European culture teaches us.

-

Single-family house, Massagno, Switzerland, 1979-1981 : © Alo Zanetta

-

Single-family house, Massagno, Switzerland, 1979-1981 : © Antonio Martinelli

CAB: Another characteristic that we observe in your houses is the use of geometry…

MB: I use geometry without fear. Although young people nowadays tend to take a hesitant view of geometry I think it’s an economic means that is part and parcel of tectonics, just like gravity. For example, talking about gravity, I very much like a house to express its own weight. If I had to design something that aimed at lightness I’d make a balloon that rises up in the sky or an airplane, but not a house: the house should take possession of the terrain.

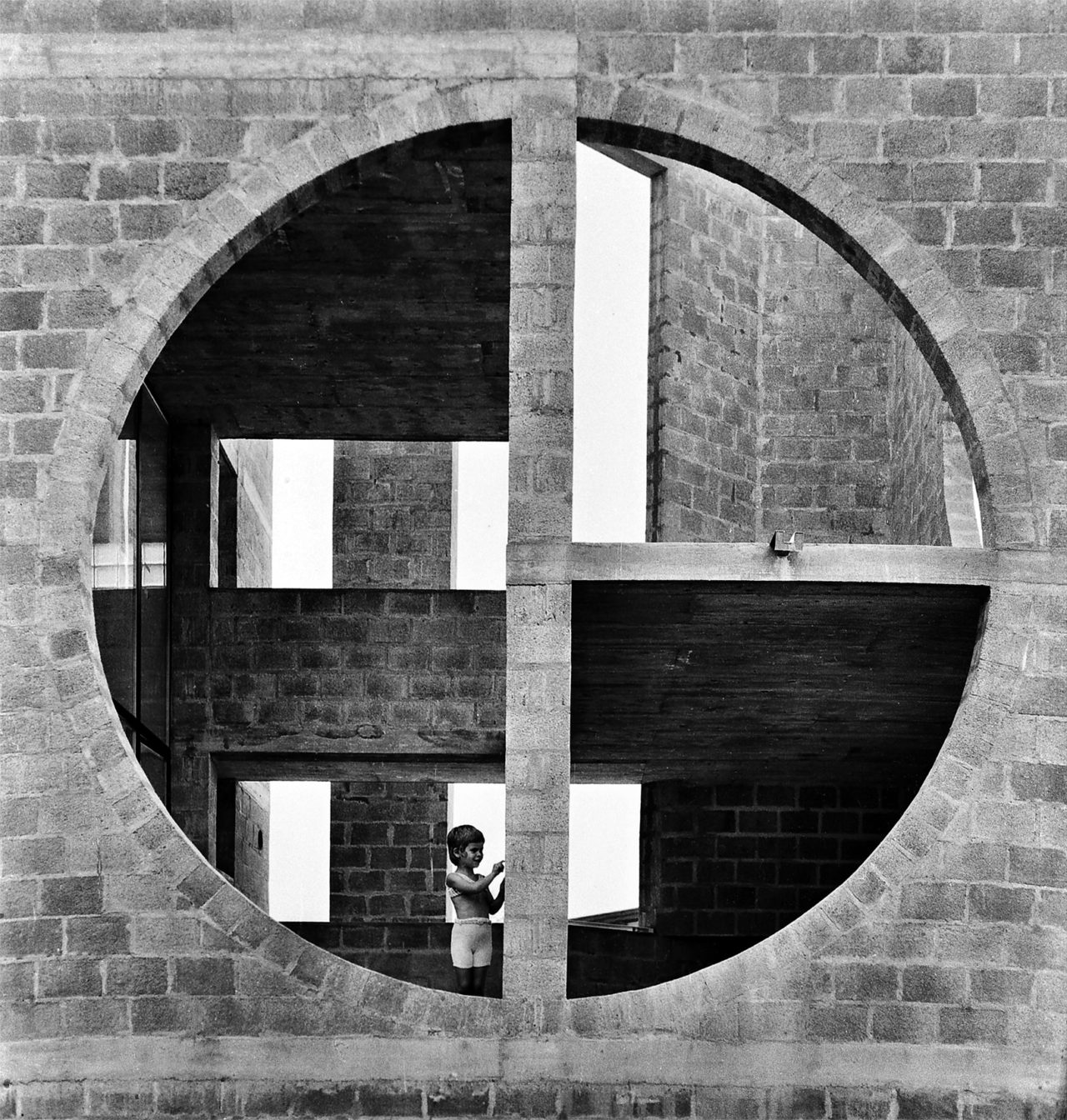

CAB: Talking about tectonics, when we visited your Single-Family House in Cadenazzo with our students a few years ago, we observed how the circular openings were created using the principle of the arch, as you utilize bricks or concrete blocks. Structurally speaking, they are not holes within a concrete wall…

MB: Yes, these openings work with the principle of the arch. It is the use of blockwork—rather than a concrete wall—that demands the arch. This technique reinforces the appearance of the blocks, which are of prefabricated concrete rather than ashlar masonry. The archetypal form of the openings, the circular shape, is the best form to maintain the structural principle of the loadbearing wall. But if the façade were in glass, for example, it would no longer follow the structural principle of the loadbearing wall, but would be a trilithic system.

-

Single-family house, Cadenazzo, Switzerland, 1970-1971 : © Maurizio Pelli

CAB: As we mentioned at the outset, starting your career with the design of single-family houses is something you have in common with Japanese architects. Is there anyone you feel you have a particular connection with?

MB: I know architects such as Fumihiko Maki, Tadao Ando and Takamitsu Azuma, architects of my own generation. We’ve met several times during international competitions and have always regarded each other with friendship and respect for the commitment to our work. Japanese architecture has given a lot to contemporary architecture. Tadao Ando also came several times to Ticino and we went to visit the houses I designed.

So, my relationship with Japanese architects has more to do with the aspect of time, with the fact that we’re from the same generation. Our clients would have been fitted similar profiles in terms of age, although they would have had very different local mindsets.

Added to this, there are different instruments to work with, and also different ways of living in the city as opposed to the countryside, which is the culture I work within. Japan also experienced a rapid technological development that Europe did not, so although we’re from the same generation we operate in very different economic and technical conditions.

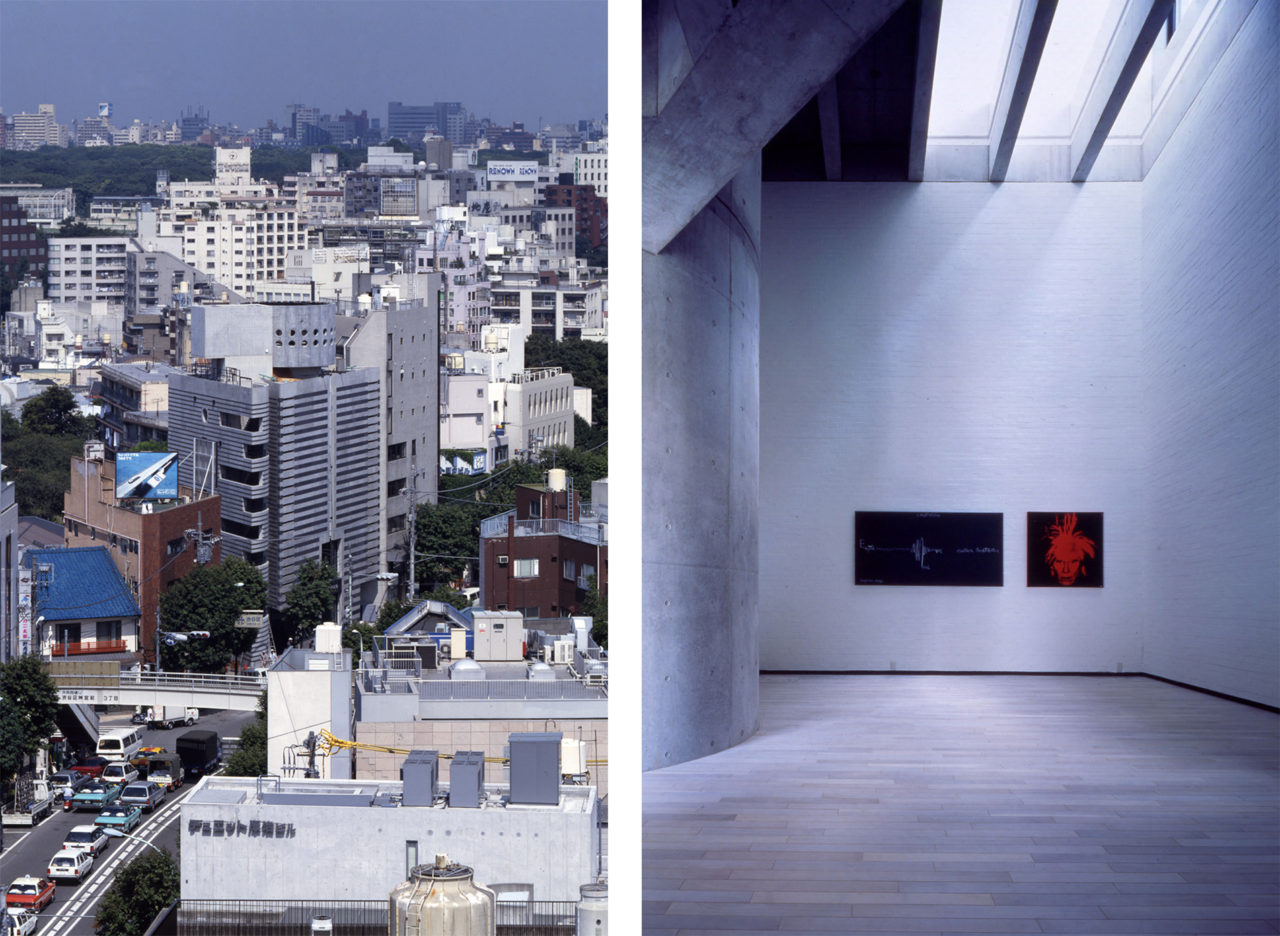

CAB: And how was your experience of designing in Japan in such a different context, with the commission for the Watari-um Museum?

MB: First of all, I felt that the economic constraints—which obviously we have here as well—are a prevalent issue in Japan. For example, in relation to the high cost of the land the site boundary line is dealt with in an almost formal way. In Europe have a little more leeway for interpretation and thus the form prevails over the boundary line. In Japan by contrast, it’s the boundary line that prevails, and this condition implies a very different way of thinking.

For example, in the design of the Watari-um Museum the corner of the site where I finally positioned the stair was too precious not to use. It is a very small piece of land, a residual space, and I liked the idea of placing the stair there, making it something like a flag that reinforces this urban corner.

-

Watari-um Museum, Tokyo, Japan, 1985-1990 : © Pino Musi

CAB: Indeed, in your single-family houses in Ticino the staircase is usually positioned at the center of the plan, along the main axis—often becoming an element that brings light and organizes the space, whereas here it is at the edge. Besides the challenges of engaging with a context like Tokyo were these decisions also developed within your design process?

MB: The design of the Watari-um was the result of a long process in which Ms. Watari’s involvement was crucial. I used to work on the design when I went to Tokyo, and she would be there too. Interestingly, whenever I would find a solution she would understand it instantly, sometimes even before I did. She also took most of my sketches!

So, the design developed directly in this way. When the engineers pointed out a problem I would draw a solution. With the stair, for example, since it had to function as fire escape and be accessible to firefighters, I decided to place it separately at the corner and make it a sign or a signal, like I said earlier. Then to gain the necessary floor space for the galleries, the technical elements are positioned in the cylindrical volume on the top.

This project is made of different parts, each with its own language. Here the windows did not have the same meaning they had in the houses. Instead of being elements to look out, they had just to bring in some light, so we worked out a system of skylights.

-

Watari-um Museum, Tokyo, Japan, 1985-1990 : © Pino Musi

What was important for me was the design of the long side of the triangular plot that overlooks the city, which is a result of the new road traced for the 1964 Olympics that cut through the pre-existing urban fabric and created this new piece of urban frontage. With the central opening I wanted to give a sense of axiality to the façade, enhancing it like a palazzo. If I could have got away with it, I would have designed only this façade!

CAB: The dynamics of Tokyo’s urban space have clearly played a crucial role in the design of the Watari-um Museum. How has the specific context of Ticino influenced the design of your single-family houses?

MB: In Ticino, land-use plans haven’t regulated development but instead have enabled a brutal process of urbanization. So, whenever we receive a commission to design a house we are prisoners of this condition, and each time we have to make a renewed effort to understand how to deal with it.

For example, with the design of the Single-Family House in Stabio, I decided to make a house with a round plan that would emphasize the diagonal of the plot and thus escape the scheme of regular plots defined by the development plan. I wanted to escape the idea of a façade against a façade by having a house that would have no façade at all.

-

Single-family house, Stabio, Switzerland, 1980-1981 : © Antonio Martinelli

Yet, considerations about the urban context apply to the design of every building, and not just to houses. What is peculiar to the house, and what makes it the main architectural theme, is that the house lives the twenty-four-hour cycle of the day: more than any other, it’s the space that puts us in relation with the world. The home brings the seasons with it, for example, in a way that the office doesn’t. Through the house, you have to be able to grasp the solar cycle and the seasonal cycle. That’s important to me.

CAB: To conclude, how about today’s situation? How have the rising trends of industrialization and globalization affected architectural practice?

MB: I feel that nowadays buildings are all tending to become the same, as we’re all using the same materials. When I look at projects in magazines I no longer understand where they’re located. But above all, nowadays, it is the client that has disappeared. We don’t have clients anymore.

For example, I am currently working on a project in Italy and I don’t know who it’s for—it was commissioned by an investment fund and has already been sold three or four times over. These funds have very different values and criteria, they’re only interested in square meters. The spaces could be offices, but they could be shops as well—they don’t even know what they want. These are very odd conditions to cope with, working for a client that I don’t even know. It’s this type of globalization that makes us lose our identity.

I prefer to be an ʻold’ architect who works with themes: if I have to design a museum, then it’s a museum, and I reflect on what a museum is today. But the reality in which I work, Ticino, is a small one. Even Zurich is inaccessible territory for me … These are hard times for architects!

-

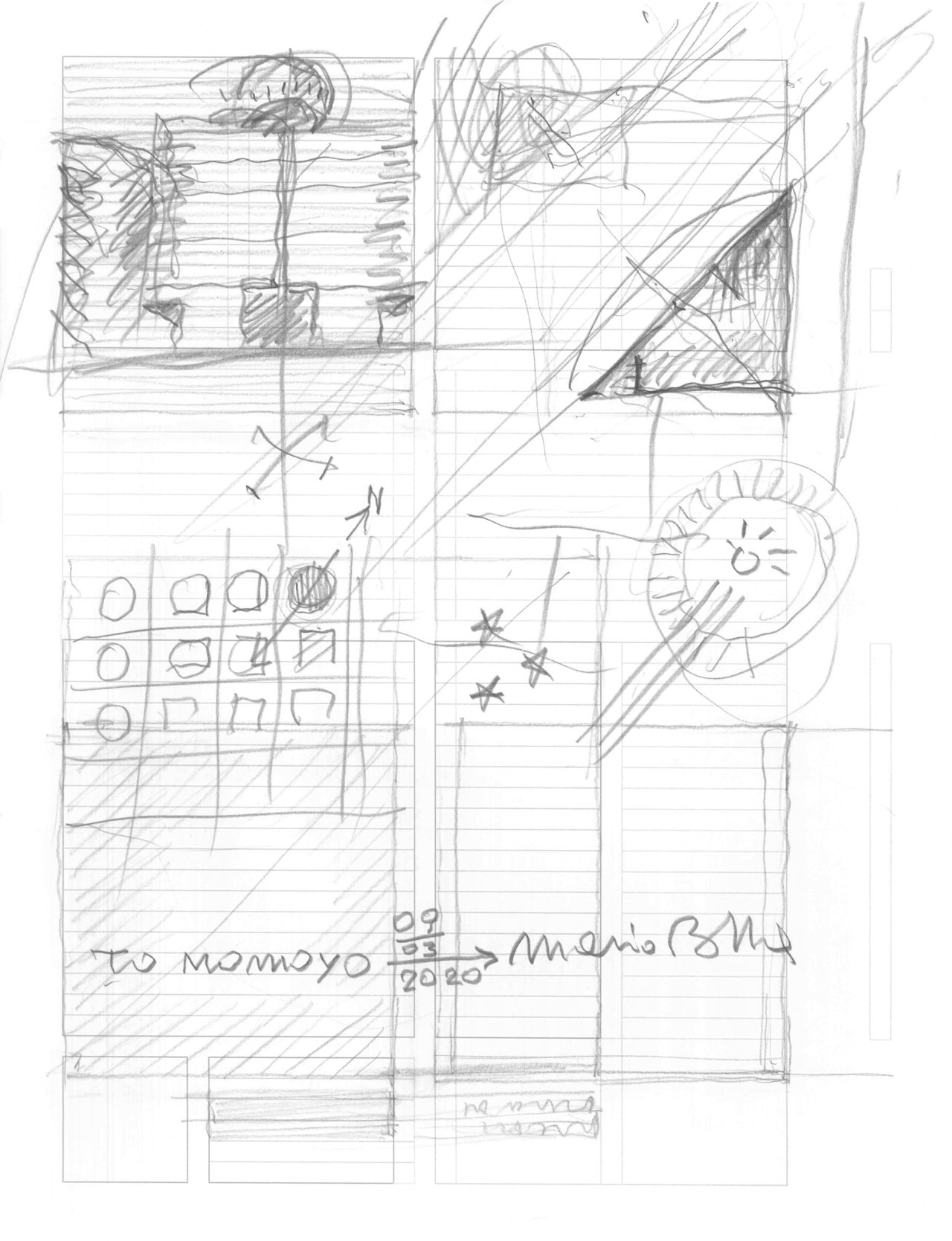

Mario Botta’s sketch from the interview

Mario Botta

Since setting up his own practice in Lugano in 1970 Mario Botta has combined his professional activity with an intense commitment to teaching, giving lectures, seminars and courses in many schools of architecture in Europe, Asia, the United States and Latin America. From his early single-family houses in Ticino his work has expanded to encompass many other building types such as schools, banks, administrative buildings, libraries, museums and sacred buildings. His work has been recognized worldwide and shown in many exhibitions. An honorary member of many cultural institutions, Botta has also been awarded honorary degrees by universities in Argentina, Greece, Romania, Bulgaria, Brazil and Switzerland.

In 1996 he was one of the key figures behind the founding of the Academy of Architecture in Mendrisio, where he taught until 2018. A further instrument for promoting the cultural debate around architecture is the Theater of Architecture in Mendrisio, which opened in October 2018.

Momoyo Kaijima

Momoyo Kaijima has served as Professor of Architectural Behaviorology at ETH Zurich since 2017. She founded Atelier Bow-Wow with Yoshiharu Tsukamoto in 1992 after her initial studies at Japan’s Women’s University and completed her post-graduate program at the Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2000. An associate professor at the Art and Design School of the University of Tsukuba since 2009, she has also taught at Harvard GSD (2003, 2016), Rice University (2014–15), TU Delft (2015–16), and Columbia University (2017). While engaging in design projects for houses, public buildings, and station plazas, she has conducted numerous investigations of the city through publications such as Made in Tokyo and Pet Architecture. She was the curator of the Japan Pavilion at the 16th International Architecture Exhibition — La Biennale di Venezia.

Simona Ferrari

Simona Ferrari has been a teaching and research assistant at the Chair of Architecture Behaviorology (ETH Zurich) since 2017 and works independently as an architect and artist. She studied architecture at the Politecnico di Milano, TU Vienna, and the Tokyo Institute of Technology as Monbukagakusho Fellow. From 2014 to 2017 she worked with Atelier Bow-Wow in Tokyo, completing several international projects. She is currently pursuing an MA in Fine Arts at the Zurich University of the Arts. Ongoing projects include the winning proposal of Europan 15 for the former industrial site of Acetati in Verbania, IT (with Metaxia Markaki).

Top image by Chair of Architectural Behaviorology

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

Swiss Window Journeys: A Conversation between Andrea Deplazes, Laurent Stalder, and Momoyo Kaijima

17 Dec 2024

Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

A Conversation with Silke Langenberg

25 Jul 2024

Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

A Conversation with François Charbonnet (Made in)

25 Jan 2024

Window Behaviorology in Switzerland

A Conversation with Christine Binswanger, Raúl Mera (Herzog & de Meuron)

24 May 2023