12 Oct 2018

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Interviews

Held during the Venice Architecture Biennale 2018, the exhibition “Liquid Light” presents an adaptive reuse project in which the Barcelona-based architect duo Ricardo Flores and Eva Prats converted an early twentieth-century building into the new home of the Sala Beckett, a theater that has held a prominent place in Barcelona’s performing arts scene since its founding in 1989. Featuring a full-scale partial reconstruction of the cultural facility as its centerpiece, the exhibit lays bare the complete process behind the six-year project through an array of original models and drawings used in its development.

In our conversation, Flores spoke about the various ideas and details condensed in the exhibit while reflecting on the path that he and his partner took to bring life to the spaces of the Sala Beckett, whose design was inspired by their initial encounter with light shining through the windows of the once dilapidated building.

To begin, can you tell us about the Sala Beckett, the subject of this exhibit?

The Sala Beckett is a theater that quickly became very influential in the theater community of Barcelona and put down deep roots in the city. The building it was relocated to already existed long before we started our restoration project. It opened for business in 1924 as a place for selling wood, but it also had a café, a theater space, and a nursery for the kids of the workers there. It was a social center for the poor working class.

It was in 2011 that the decision was made to renovate the building and you were commissioned to carry out the redesign. What condition was the building in at that time?

The building had been abandoned for 30 years by the time we were selected to work on the project. It was in desperate need of restoration, especially considering its glorious past. These are photographs that we took before we began on construction.

-

Photos © Adrià Goula

These pictures capture the very first moments of our encounter with the light in the building. The light was very dramatic and also promising for the building’s new life as the Sala Beckett. Seeing this made us decide to restore the building and to try to make it useful again for the future. The same light is still there in the Sala Beckett today.

The word “light” is also in the exhibit’s title, “Liquid Light”. What is the concept behind the exhibit, and how does it relate to the Biennale’s theme of “Freespace”?

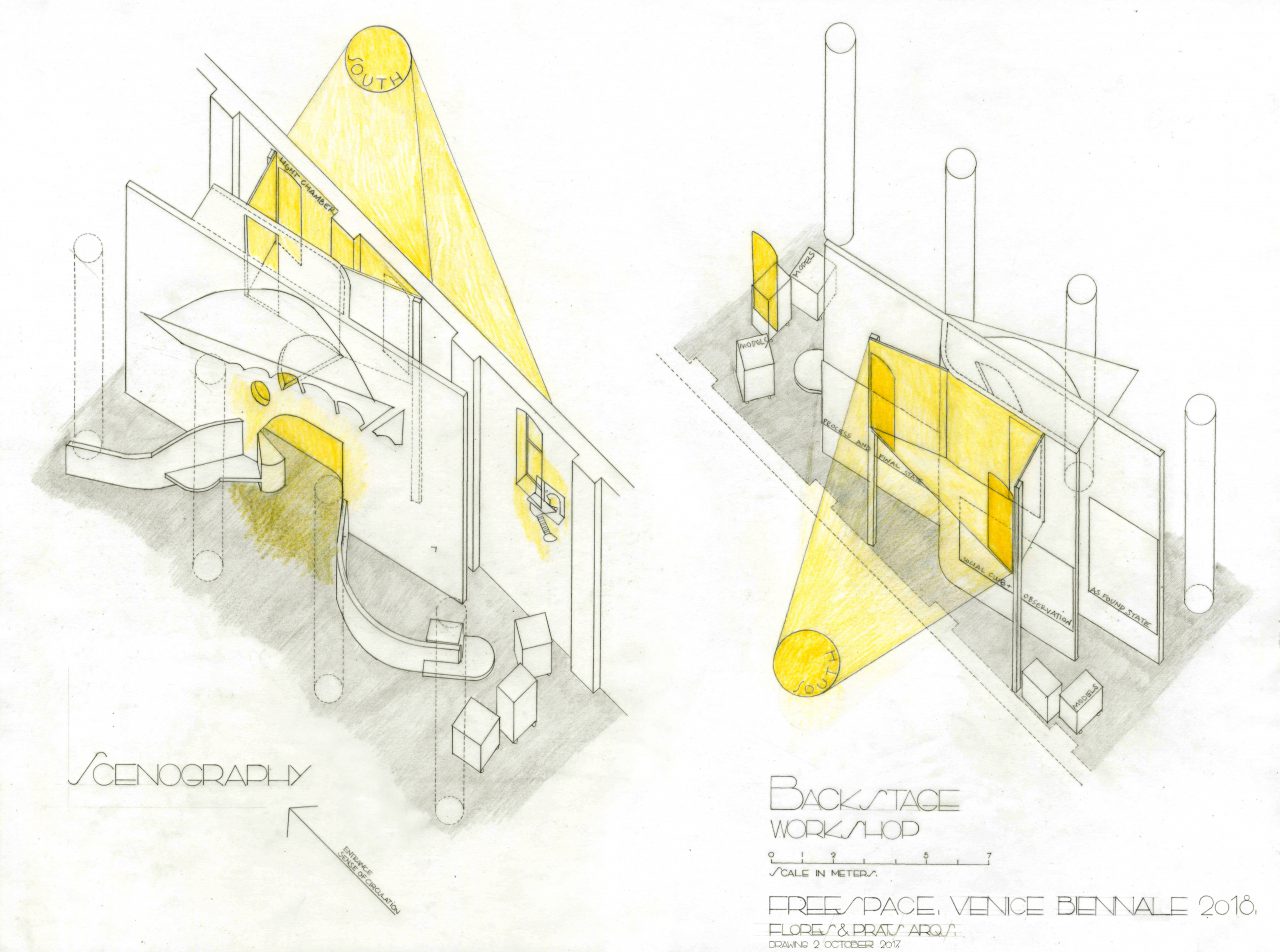

We wanted to respond to the theme of “Freespace” by using natural light because we have worked with lightwells in many of our restoration projects. This led us to the idea of opening up the windows in the venue to bring in natural light. From there we decided to bring in fragments of the Sala Beckett by building a full-scale model of the theater around these windows. The light funneled in from the windows flows into another window on the inner wall of the model and lights up the model from inside. This light then spills out from the windows and entrance on the front side of the model, inviting people to enter.

-

Entrance of the full-scale model

Photo © Adrià Goula

When you walk into the full-scale model, you start to understand what’s happening with the light and where it’s coming from. First you see the light coming in and filling the entire entrance space, and then you realize that the light is in fact natural light brought in from outside through the two windows. You can see the same light in the actual Sala Beckett. We refer to such light as “liquid light”, and we used this as the title of the exhibit.

Why do you call it “liquid light”?

Because it’s a kind of light that can be manipulated and worked to not only flow down with gravity but also spread out horizontally and fit to spaces of various sizes. It has a fluid, water-like quality that lets you redirect it in whatever way you want to fill a room with light.

-

Image courtesy of Flores & Prats

What is exhibited inside the full-scale model?

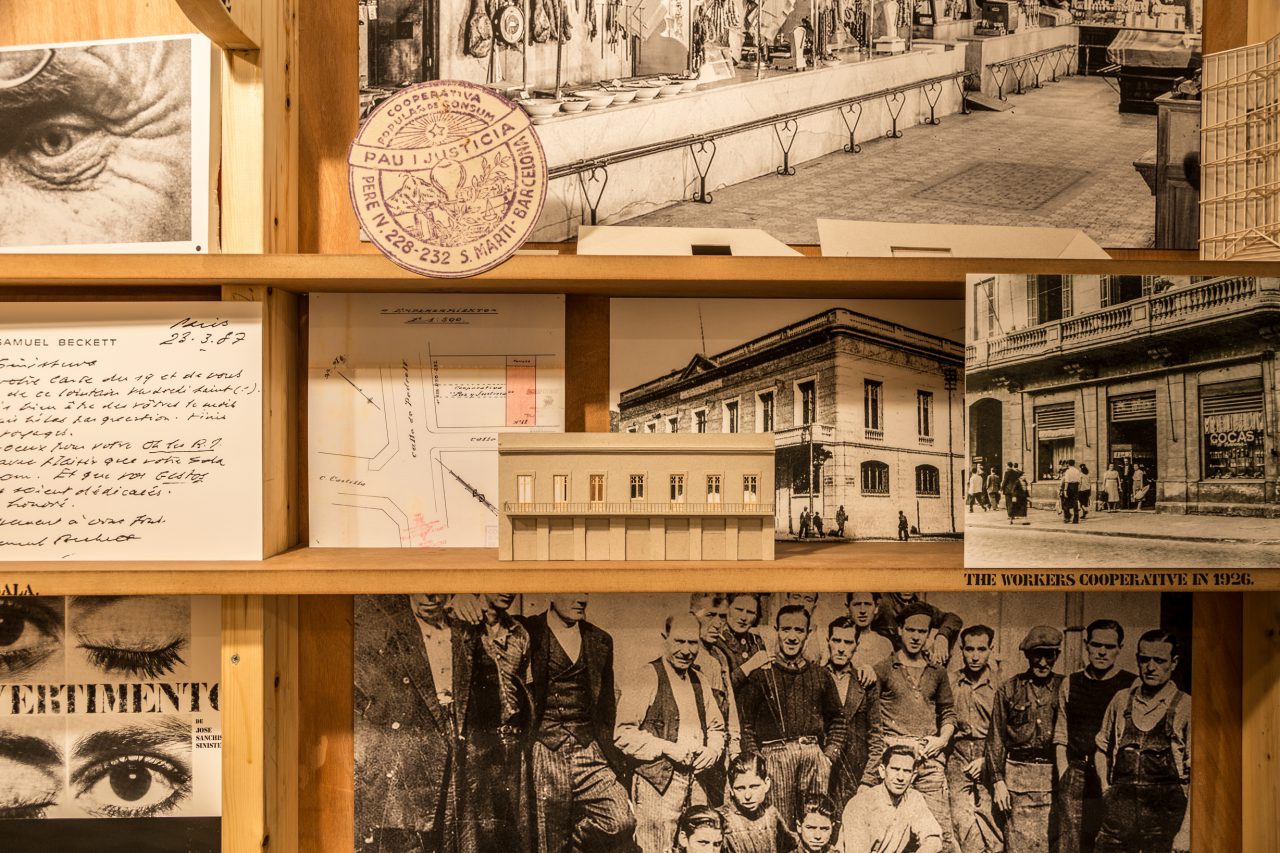

If you look at the model as a stage set, you could say that the space inside it is the backstage. There you can understand the process behind the restoration project that we developed from 2011 to 2016. Everything from our work for the competition to our preparations for the Biennale is condensed in the 15-meter-long exhibit.

-

Photo © Adrià Goula

-

Research materials and study models used to develop the project

Photos © Judith Casas

Can you tell us more about the exhibited models and drawings?

Most of them were actually used in developing the restoration project. The first thing we had to do in the project was to figure out a way to expand the building because there wasn’t enough space for all the programs. We kept making studies for the roof, windows, and floors until we found the final solution.

And then there was a process of drawing. We spent a whole month just making drawings for the competition. We started by drawing the building as it existed. It was important for us to draw everything we thought needed to be restored and used somehow. So, we drew every door and window, and we tried to draw not only objects but also the things around them because it’s not just the window that makes the window, for example; its surroundings are also part of the window. We drew and modeled everything and built a huge inventory of things to reuse somewhere in the new design. Our trying to adapt these things to the new program was in a way a compromise between creating a work that was very important for us and preserving all the workers’ memories that lived there in the building for many, many years. That was one thing we didn’t want to erase, so we drew and modeled everything.

-

Flores & Prats’ studio in Barcelona

-

Tracings of doors and windows

-

Paper models of the windows and doors of the original building

-

Making of a map of the windows and doors in the new Sala Beckett Photos © Judith Casas

Looking at the models and drawings, we really get the sense that the treatment of light was at the core of the design of the Sala Beckett.

Exactly. All the central parts of the original building were illuminated by light brought in from outside. Understanding how the light passed through the different windows was important for us to be able to relocate them and make them useful again for the new program.

Don’t erase the memories of the original building, make sure that the new Sala Beckett has a good presence, and make full use of our experience as architects. These were the three points we kept in mind while working on the drawings. To create a work of architecture that shines, you shouldn’t make your presence strongly felt in it, though you should also have the courage to break things when you need to. If you have this mindset, you will see that the light helps, the windows help, the doors help—everything can help your design.

I think we were able to create a convincing building in the Sala Beckett project because we developed a good understanding of its history and context, and we were able to make use of this in the design. We were able to make a place where people in the present can get in touch with the spirit of the people who used to visit the building in the past.

-

Interior of the new Sala Beckett Photos © Adrià Goula

What else are you showing in the exhibit other than these drawings and models?

There’s a little documentary film in which we interview designers and artists who work with renovating spaces and materials. We’re also exhibiting a model that shows how people are using the new Sala Beckett. By looking at the model, you can understand how people have found places to occupy in the middle of the vestibule, in the theater, in the dressing rooms—all over. It’s like they are performing little plays. It’s very nice because you can see how the building works all at once.

We have also put on display our first proposal for Freespace that we made back in August of last year. So, we’re actually showing the process of making the exhibit in the exhibit itself. We had the idea of bringing all those materials to the Biennale as a way of getting young architects and students to spend some time on the benches. Also, we felt it was important to show how much time we spent in the office to create what may seem very, very simple when in fact we have put in a terrible amount of work to make it happen.

-

© Adrià Goula

-

Bottom two photos © Adrià Goula

Can you end by telling us what “freespace” means to you?

I understand “freespace” to be like a gift that an architect offers even though people didn’t ask for it. For example, a courtyard illuminated by a beautiful light. Even if it isn’t in your own house, you might see it as a pedestrian walking by and take joy in its beauty. It’s something that may not necessarily be productive, but it can give people joy. That’s what “freespace” is for me.

Flores & Prats

Architecture studio based in Barcelona, which combines design and constructive practice with intense academic activity. After their experience at Enric Miralles’ studio, Ricardo Flores and Eva Prats eveloped a career where research is always linked to the responsibility to make and build, where importance is given to participating in the interpretation of the constructed work. Their projects, most of which are the result of opencompetitions, have investigated in fields such as rehabilitation, social housing, or urban public spaces and neighborhood participation. But the office has also developed mobile or portable projects, has experimented with the use of film to document the architecture, and with menus of edible architecture developed for the exhibitions of its work in Barcelona and Copenhagen.

The work of Flores & Prats has been widely awarded, published and exhibited. They have been part of the Emerging Offices Wallpaper Directory in 2007, won the Grand Prize for the Best Architectural Work of the Royal Academy of Arts in London 2009 for the rehabilitation project Mills Museum in Palma de Mallorca, and the International Prize Dedalo Minosse in Vicenza 2011 for the New Microsoft Campus in Milan. Most recently, they were awarded the City of Barcelona Prize of Architecture and have received a special mention in the Spanish National Architecture Awards for their work Sala Beckett Theatreand Drama Centre, and were awarded the City of Palma Prize of Architecture for the project Casal Balaguer Cultural Centre. Their work has been exhibited at La Biennale di Venezia in 2012, 2014, 2016, and 2018 and nominated for the Mies van der Rohe Prize 2005, 2015, 2016 and 2017. In 2018 they have been named the Architects of the Year in the AD Awards.

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Thresholds between Coexistence and Architecture

25 Jun 2019

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Interview with Tom Emerson, 6a architects

22 Apr 2019

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Windows: Openings and devices

12 Dec 2018

The 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia 2018

Spaces In Between

01 Oct 2018