Series Windows of Japanese Modernist Architecture

A Culmination of Sutemi Horiguchi’s Aperture Designs:

The Tokoname City Municipal Ceramics Research Institute (Tokoname Tounomori Research Institute)

15 May 2025

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Columns

- Essays

The exhibition Explorations of Horiguchi Sutemi: Modernism, Rikyu, Garden, Waka opened in August 2024 at the National Archives of Modern Architecture of the Agency for Cultural Affairs. Katsuhiro Kobayashi, the archive’s Chief Senior Specialist for Architectural Documents, sheds light on the appeal of one of Sutemi Horiguchi’s representative works, the Tokoname City Municipal Ceramics Research Institute (now the Tokoname Tounomori Research Institute), which is replete with features reflecting the architect’s careful consideration of openings.

A Masterpiece of Postwar Modern Architecture in a Ceramics Capital

The city of Tokoname, Aichi, situated in the central part of the Chita Peninsula’s western coast, facing Ise Bay, has a long history as a site of ceramic production. Tokoname ware is one of Japan’s six historic ceramic traditions (the others are Seto, Echizen, Shiga, Tamba, and Bizen) and is considered the oldest and largest among them. Even the city’s name is rooted in the earth: it came to be called “Tokoname” because its clay beds (常 toko: “bed”, as in “ground”) are smooth (滑らか nameraka). Many historical sites related to the ceramic industry can be found throughout the city.

Located among gentle hills a little way out from the city streets, the Tokoname City Municipal Ceramics Research Institute (now the Tokoname Tounomori Research Institute) stands as a refined building with an undertone of light purple. Its asymmetrical composition is marked by the horizontal lines of its deep eaves and balcony railings, an entrance canopy articulating the point of ingress, and a sculptural daylighting penthouse on the rooftop. It also has an enigmatic quality to it; without prior knowledge, one would probably wonder what purpose it serves and when it was built.

The building is a major late-career work by the architect Sutemi Horiguchi (1895–1984) from 1961. Considering the period when it was built, it is a particularly noteworthy masterpiece of Japanese postwar modern architecture. Horiguchi explored various ways of designing apertures in this building, and its exhibition room, in particular, was among the finest interior spaces in Japan at the time.

History of the Building

The Tokoname City Municipal Ceramics Research Institute was built for the purpose of promoting ceramic art in 1961 with an endowment from Chozaburo Ina, who founded Ina Seito (now LIXIL) and also served as Tokoname’s first mayor. Housing an exhibition room, a meeting room, and administrative offices, the building is adjoined at the back by a workshop, material warehouse, and lodgings. The exhibition room features items ranging from large works of Old Tokoname ware, dating from the late Heian to Kamakura period, to pieces by master artisans of the Edo period and later. The Tokoname City Folk Museum was built nearby in 1981 (renovated in October 2021), and in 2012, the research institute, museum, and workshop were consolidated as the Tokoname Tounomori [Tokoname Tounomori Museum] with the aim to comprehensively “cultivate and pass on Tokoname ware and create and promote ceramic culture”. As part of this restructuring, the Tokoname City Municipal Ceramics Research Institute was renamed the Tokoname Tounomori Research Institute.

The Tokoname City Municipal Ceramics Research Institute gained greater recognition as an important work of modern architecture when Docomomo Japan listed it in 2014. Furthermore, the building and its main gate were designated as Tangible Cultural Properties of Japan in 2023, adding to its growing reputation as a masterpiece more than half a century after its construction.

The Building’s Apertures

Owing to its primary function of displaying ceramics and its deep cantilevered eaves and balconies, the Tokoname City Municipal Ceramics Research Institute appears devoid of conspicuous openings from a distance. This might lead one to think that the main focus of the design was the balanced composition itself, formed by the asymmetrically arranged deep eaves, horizontally articulated railings, and sculptural rooftop element. As one moves closer, however, a variety of creatively designed apertures reveal themselves.

The entrance makes use of glass blocks whose edges are painted in purple, such that the entire surface of glass emits a soft purple glow. The double door is designed with a mirrored pair of distinctive semicircular push plates, such that when the door is closed, a golden, moon-like circle appears to float between the purplish glass block surfaces.

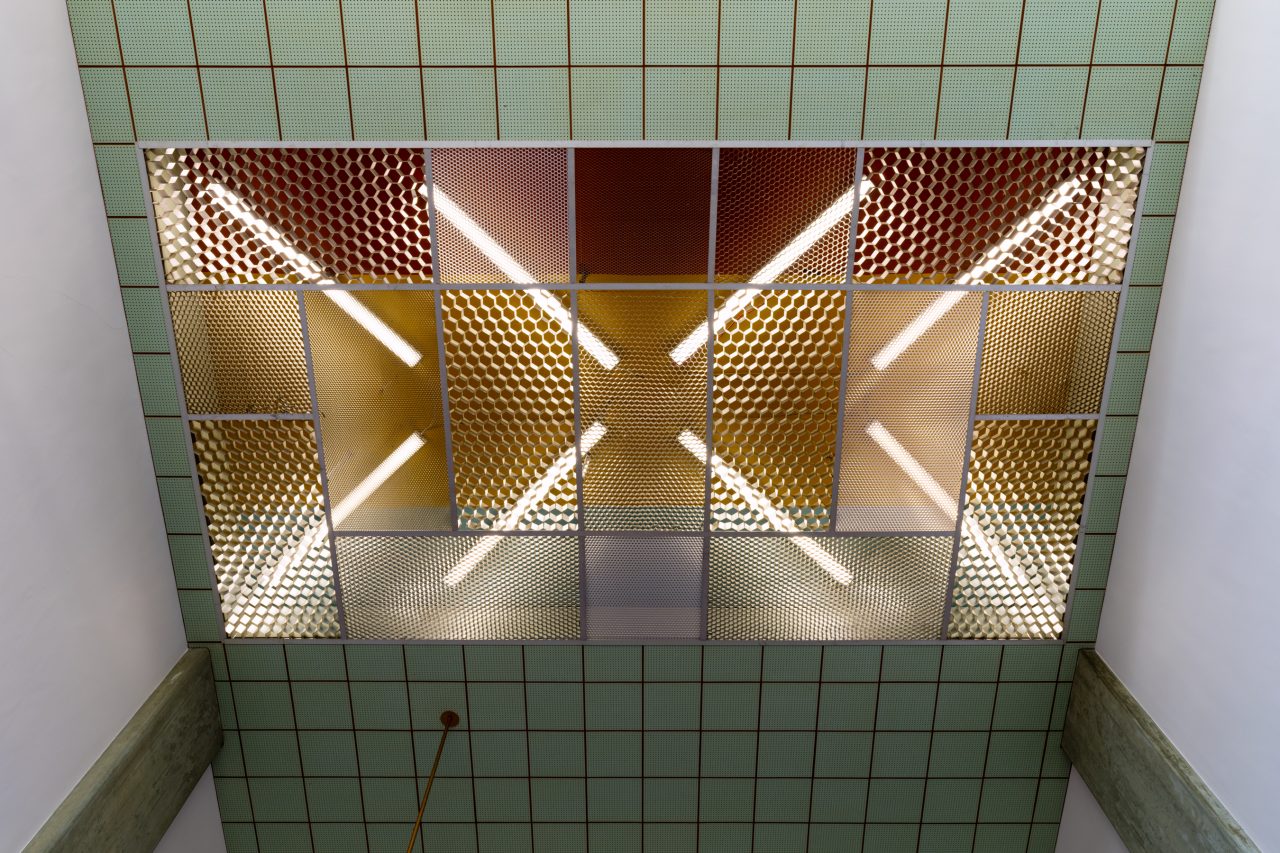

The double-height entrance hall has a distinctive staircase with a weightless design achieved using tension members. Overhead is a luminous ceiling, consisting of a radial array of fluorescent lights and three types of light louver grids arranged beneath them in a way that evokes tatami floor patterns. The shapes and aperture ratios of each type of louver grid are intentionally varied, and make for a peculiar ceiling design as a whole.

-

Entrance hall with suspended staircase.

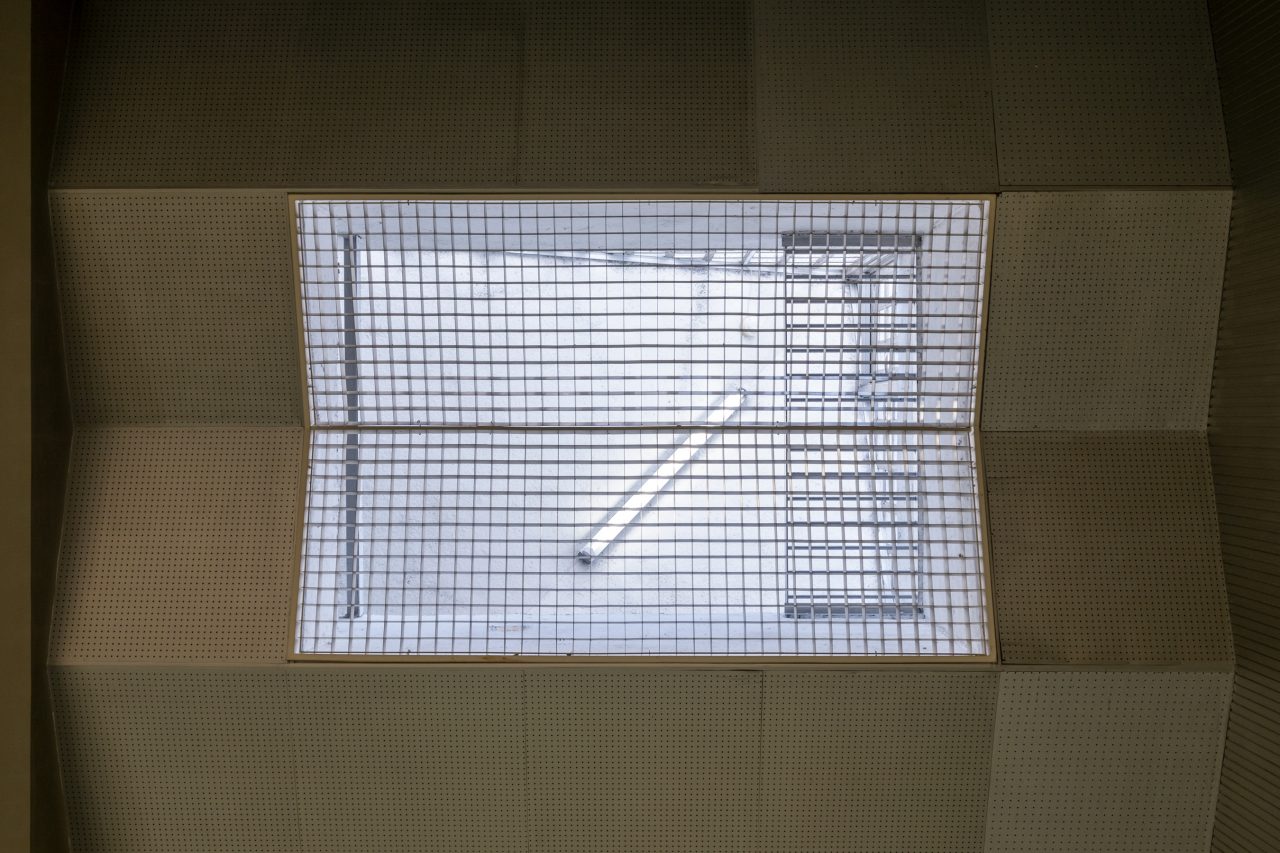

The exhibition room, located beside the entrance hall, is the building’s central space and is especially illustrative of Horiguchi’s deep interest and versatile creativity in the design of apertures. The space is composed of silver-toned wall and ceiling surfaces to enhance the prominence of the ceramic works. The ceiling, formed of folded planes, is punctuated by four louvered skylights, which filter the light drawn in from the penthouse. Arranged in rotational symmetry, these louvers lend the space with a sense of movement. By looking up through the louvers from directly below, one can see that there are service catwalks, as well as artificial lights fixed to the penthouse’s slanted roof. The three-dimensional composition of the light from these four ceiling apertures, the horizontal bands of light spilling from the niche displays along the walls, and the light emanating from the linear display case in the center of the room, render this exhibition space an enduring masterpiece that makes great use of light.

-

The exhibition room’s silver-painted walls. -

The works in the central display case are set atop glass and evenly illuminated by built-in lights from above and below.

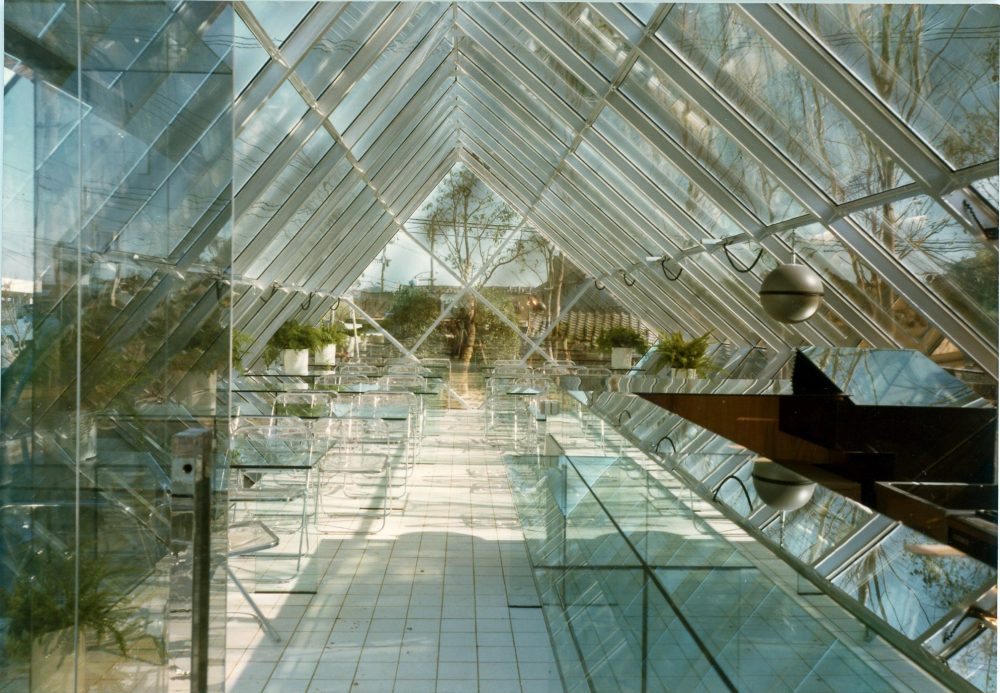

The penthouse, though made for the skylights, also serves as a kind of sign for the facility when viewed from afar. It incorporates tricky details, as its lattice windows had to be fitted into rough openings that are triangular in elevation. Furthermore, the openings within the lattices are fitted with ribbed glass, adding to the complexity.

Considering that it was built in 1961, the exhibition room is radical in its design. While there are other notable exhibition facilities of postwar modernism, such as The Museum of Modern Art, Kanagawa (1951), Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum (1952), and The National Museum of Western Art (1959), it stands apart from their exhibition spaces in the way it utilizes the light emanating from the apertures of the display cases. In fact, it could be described as representing the most diverse exploration of apertures and lighting in all of early 1960s Japan.

For Horiguchi, apertures included more than just typical windows; he considered any opening facilitating the interplay of light or sightlines an aperture. This includes openings beyond the building envelope, such as the veranda bordering the second-story meeting room and Japanese-style room, which is furnished with an outdoor bench for viewing the surroundings, while the beams above form louvers to allow sunlight to filter through. As a consequence of incorporating such diverse apertures, Horiguchi also had to devise many solutions to reconcile their junctures. For example, consider the space combining the reception room and tearoom on the first story. The exterior sliding sash windows and the interior shōji [translucent lattice screen] window do not align, as the dimensions of the former correspond to the spacing of the concrete columns, while those of the latter correspond to the configuration of the tearoom. Although designed to be inconspicuous from within, this shift is clearly perceptible from the outside.

Sutemi Horiguchi’s Diverse Aperture Designs

Let us look back at the career of architect Sutemi Horiguchi through the lens of his aperture designs. Horiguchi played a central role in founding the Bunriha Kenchikukai [Successionist Architecture Group] (1920), which is regarded as Japan’s first genuine modern architectural movement, and he authored some of Japan’s most emblematic works of International Style architecture in the 1930s. By examining the apertures in his work—such as the geometric windows punched out of the walls of the Shienso (1926), the horizontally pronounced windows of the Oshima Weather Station (1938), and his early adoption of glass block windows in Japan at the Wakasa House (1939)—one can appreciate how he responded sensitively to European modernist trends and deftly assimilated their evolving apertures into his own designs. Alongside his design work, he also made excellent scholarly contributions to the study of Japanese tearooms and sukiya-style architecture from the late 1930s onwards. Building on his research findings, he created works of modern sukiya architecture, such as the Hasshokan (1950), through which he reinterpreted traditional Japanese apertures—that is, airy openings composed of columns and shōji.

From 1949 to 1965, Horiguchi taught at Meiji University’s architecture department, and he designed a series of reinforced concrete buildings for the university’s campus. The Tokoname City Municipal Ceramics Research Institute also dates to this period. Horiguchi demonstrated his creative prowess across diverse disciplines beyond architecture, including the Japanese arts of tea, poetry, and garden design. As a connoisseur of various cultural arts, he was undoubtedly particularly inspired by the opportunity to design a facility dedicated to contributing to ceramic arts.

Through his research and practice of both modern architecture and sukiya architecture, Horiguchi deeply understood how apertures shape the character of buildings and spaces. The Tokoname City Municipal Ceramics Research Institute stands as a culmination of his interest and expertise in designing apertures, brought to life through his seasoned hand.

Explorations of Horiguchi Sutemi: Modernism, Rikyu, Garden, Waka

Dates: August 8 – October 27, 2024

Venue: National Archives of Modern Architecture, Agency for Cultural Affairs (Yushima Local Common Government Offices, 4-6-15 Yushima, Bunkyo, Tokyo 113-8553)

Details: See website of the National Archives of Modern Architecture, Agency for Cultural Affairs

The exhibition features a life-size fold-up model of the Yosuitei that was produced for Windowology: New Architectural Views from Japan, an exhibition organized by the Window Research Institute and presented at the Japan Houses and Villum Window Collection.

Katsuhiro Kobayashi

Born 1955. Professor Emeritus of the Tokyo Metropolitan University and Chief Senior Specialist for Architectural Documents at the National Archives of Modern Architecture, Agency for Cultural Affairs. Specializes in modern architectural theory and design. Graduated from the architecture department at The University of Tokyo in 1977. Completed the doctoral program at The University of Tokyo in 1985. Doctor of Engineering. Taught as a lecturer, associate professor, and professor at the Tokyo Metropolitan University before retiring from its Graduate School of Urban Environmental Sciences in March 2020. Chief Senior Specialist for Architectural Documents at the National Archives of Modern Architecture since April 2021. Major publications include Kenchiku kōsei no shuhō: Hiritsu, kikagaku, taishō, bunsetsu, shinsō to hyōsō, sōkōsei [Techniques of Architectural Composition: Proportion, Geometry, Symmetry, Segmentation, Deep Layers and Surface Layers, Layered Compositions] (Shokokusha, 2000); Kenchikuron jiten [Encyclopedia of Architectural Theory], ed. Architectural Institute of Japan (principal editor) (Shokokusha, 2008); Architectural Conversions in the World II (Kajima Institute, 2013); Skyscrapers: Challenge of Tall Buildings in the World (Kajima Institute, 2015); and From Architectural Conversion to Urban Regeneration (Building Center of Japan, 2022).

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Windows of Japanese Modernist Architecture

The Windows of Tomoya Masuda’s Naruto Cultural Center: A Faintly Bright Louvered Space

17 Jun 2025

Windows of Japanese Modernist Architecture

The Diversity of Windows in Kiyonori Kikutake’s Serizawa Literary Center (Serizawa Kojiro Memorial Museum)

25 Dec 2024

Windows of Japanese Modernist Architecture

The Windows of Hiroshi Hara’s Awazu House: Spaces of Light Illuminating the Darkness

26 Apr 2024

Windows of Japanese Modernist Architecture

Windows of the Aichi University of the Arts

by Junzo Yoshimura and Akio Okumura:

The Concrete Science of Living with Nature19 Jan 2024