Louis Kahn and the Power of Shadow

06 Jan 2025

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Columns

Does shadow have the power to give form to architecture? The increasing number of transparent buildings and LED installations enforces the impression that light has eliminated the relevance of shadow. But to answer that question, let’s look back at an Estonian-born master of light whose architecture was shaped by shadow: Louis Kahn.

As identified by Leonardo da Vinci, we often encounter three types of shadows: attached shadow, shading, and cast shadow. The attached shadow falls on the body itself – like a cantilever roof causing a shadow on the façade. The second type refers to bright and dark contrasts, which are inherent to the form and depend only on the source of light, e.g., a ball-shaped pavilion, which, even under an overcast sky, shows a darker zone in the lower part. The third, cast shadow, could result from a tall building generating a shadow on the street due to the projection of the building’s outline.

Kahn’s archetypal forms trace back to Greek architecture, which he studied in the 1950s: “Greek architecture taught me that the column is where the light is not, and the space between is where the light is. It is a matter of no-light, light, no-light, light. A column and a column bring light between them. To make a column which grows out of the wall and which makes its own rhythm of no-light, light, no-light, light: that is the marvel of the artist.”

-

A bench built into the interior wall of the classroom of the First Unitarian Church, Rochester, New York (1969) with fixed windows on either side.

Photo courtesy of The Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum, bequest of Minor White © Trustees of Princeton University

However, light was also a central element in Kahn’s philosophy because he regarded it as a “giver of all presences”: “All material in nature, the mountains and the streams and the air and we, are made of Light which has been spent, and this crumpled mass called material casts a shadow, and the shadow belongs to Light.” For him, light is the maker of material, and material’s purpose is to cast a shadow.

And because Kahn believed that the dark shadow is a natural part of light, he never attempted to create a purely dark space for a formal effect. For him, a glimpse of light elucidated the level of darkness: “A plan of a building should be read like a harmony of spaces in light. Even a space intended to be dark should have just enough light from some mysterious opening to tell us how dark it really is. Each space must be defined by its structure and the character of its natural light.” As a result, the light source is often hidden behind louvers or secondary walls, thus concentrating attention on the effect of the light and not on its origin.

-

The brick wall partitions inside the Arts United Center (1961) feature carefully crafted openings.

© Jason R. Woods

-

South galleries of the Kimbell Art Museum (1969-72) feature arched ceilings with slits at the apex. Beneath them are crescent-shaped lighting fixtures called “lunettes,” designed to soften Texas’s intense sunlight while bringing natural light into the interior.

Louis I. Kahn (1901–1974), architect Photograph: Robert LaPrelle © 2013 Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth

The “mysteriousness” of shadow was also closely linked to evoking silence and awe. For Kahn, while darkness evokes the uncertainty of not being able to see, of potential dangers, it also inspires deep mystery. It is in the hands of the architect to evoke silence, secrecy, or drama with light and shadow—to create a “treasury of shadows,” a “Sanctuary of Art.”

Thus, walking through the sequence of openings at the portico of the Salk Institute brings to mind the dark silence of a cloister. Dark shadow lines and holes, from the precisely defined molds, offer a fine texture on the massive walls. The white stone and the gray concrete walls present a monotone three-dimensional canvas for the play of shadows. Shade becomes an essential element to reveal the arrangement and the form of Kahn’s monolithic volumes.

-

Salk Institute for Biological Studies

La Jolla, California (1965)

© Nils Koenning -

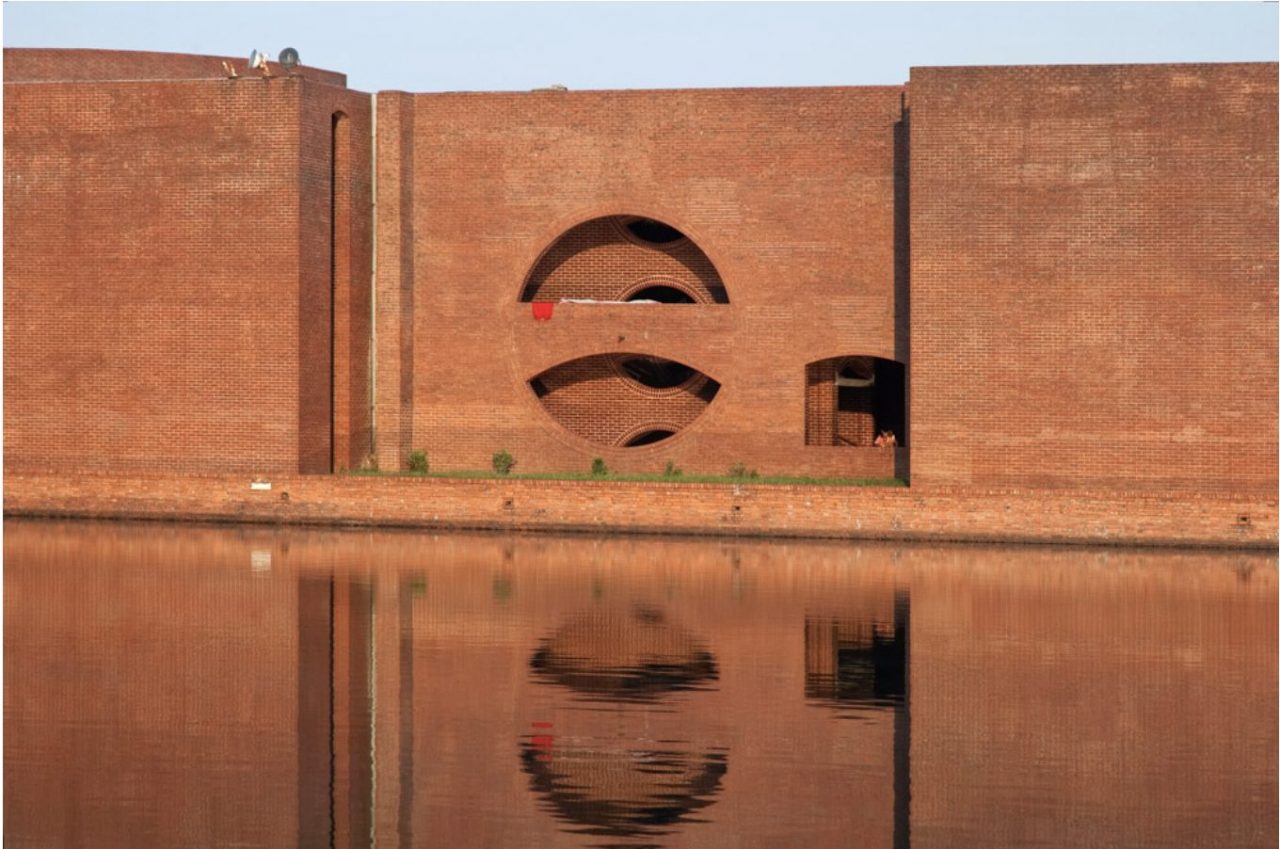

And even though Kahn erected many buildings in regions exposed to extreme sunlight (such as India and Pakistan), he did not design his buildings to protect users from the sun but rather to preserve the sanctity of the shadow. He didn’t believe in artificial shade, such as ʻbrise-soleils,’ explains Ingeborg Flagge, the former director of the German Architecture Museum, who curated the exhibition The Secret of the Shadow. Instead, he used windows and doors in his double walls to direct the light into the interior. As Kahn describes the large open windows and doors of the Indian Institute of Management: “The outside belongs to the sun, and on the inside, people live and work. In order to avoid protection from the sun, I invented the idea of a deep intrados that protects the cool shadow.”

Kahn’s path of designing with shadow attracted numerous followers, such as Tadao Ando with his Church of Light, Peter Zumthor with his Therme Vals, and Axel Schultes with his Crematorium. They all include shadow as a form-giver for silent spaces. This perspective presents a pleasant counterpoint to today’s architecture, which strives for dynamic and bright icons.

-

Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, India (1997)

© Jeroen Verrecht

References:

1. Buttiker, Urs. Louis I. Kahn: Light and Space. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1994.

2. Wurman, Richard Saul, ed. What will be has always been. The words of Louis Kahn; Progressive Architecture 1969, Special Edition, Wanting to Be: The Philadelphia School. London: MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1973.

3. Lobell, John. Between Silence and Light. Spirit in the Architecture of Louis I. Kahn. Boulder, Colorado: Shambhala Publications, 1979.

4. Merrill, Michael: Inventio and Tectonics in the Work of Louis Kahn, Perspecta: The Yale Architectural Journal Vol. 21, 1984.

This essay was originally published on ArchDaily, April 23, 2013, and has been revised with a new selection of photographs and updated information. The original article can be read on “Louis Kahn and the Power of Shadow.”

Thomas Schielke

Thomas Schielke studied architecture at the University of Technology in Darmstadt, Germany, completing a doctorate in engineering (Dr-Ing) at the same institution.

Thomas works as a lighting design trainer for the lighting manufacturer ERCO, where he teaches lighting and designed an extensive online guide for architectural lighting. He is the co-author of two books: Light Perspectives – between culture and technology (2009, with Martin Krautter) and SuperLux – Smart Light Art, Design & Architecture for Cities (2015, with Davina Jackson), and has published numerous articles on lighting design and technology.

Thomas has also presented lectures at a number of American and European universities, including Harvard GSD, MIT, Columbia GSAPP and ETH Zurich. His regular column “Light Matters” in ArchDaily discusses various aspects of architectural lighting.