01│Antoni Gaudí: A "Sensible Architect"

11 Dec 2024

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Essays

Introduction

The window is an extremely popular motif among architects. It would be natural to think that the possibilities for window design flourished after the mass production of plate glass began in the mid-19th century. However, aside from special cases such as the Crystal Palace (1851), which was built as a pavilion for the inaugural World Expo, structures enveloped in glass or equipped with large glass windows and skylights did not immediately spread beyond monumental buildings, such as railway terminals, government halls, and banks. Glass windows also offered benefits for housing with their ability to introduce sunlight and views while keeping out the wind, yet few residential works appeared that incorporated them as a primary design feature. Victor Horta’s Maison & Atelier Horta (1901) in Brussels, with its stairwell skylight and large glazed openings on the front façade, can be considered one pioneering example.

-

Maison & Atelier Horta, exterior view (middle two buildings).

Let’s take a look at the window designs presented in the work of three architects from that era who explored the possibilities of the window and gave it new meanings: Antoni Gaudí i Cornet (1852–1926), Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959), and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969).

Antoni Gaudí: A “Sensible Architect” Mindful of Amenity

Perhaps owing to the fact that the Sagrada Família in Barcelona is scheduled for completion in 2026, Gaudí and his work have lately been frequently spotlighted in the Japanese media. Images of his church are even featured in ads for package tours to Spain. I should note that, personally, I do not consider any part of this building other than its four eastern steeples as the work of Gaudí, even though they may be based on his original vision. This is because Gaudí was the type of architect who finalized his designs on the worksite while consulting with the builders.

The media tends to focus on Gaudí’s “eccentric forms” while rarely directing attention to how the windows in his work—particularly his residential work—were designed with detailed consideration for lighting and ventilation, which was rather innovative for his time. Here, I would like to highlight the considerate window designs he developed for buildings including the Casa Batlló (1904) and Casa Milà (1906).

-

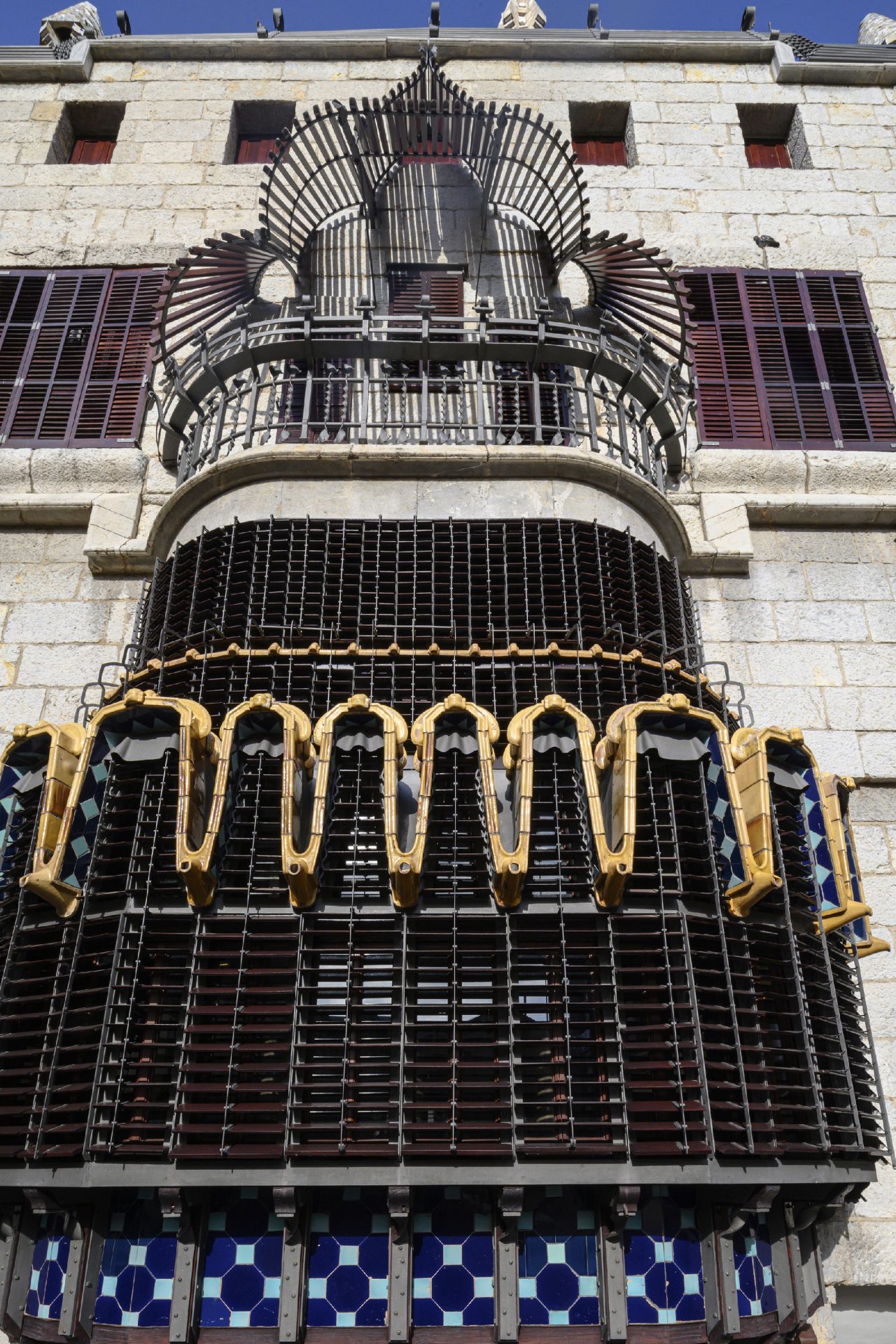

Casa Batlló, upward view of the front façade.

The Casa Batlló is a renovated residential building. If you look at the third- to fifth-story-portion of its façade facing the Passeig de Gràcia, one of Barcelona’s main avenues, you will see that the windows are regularly aligned. This is because Gaudí retained the windows from before the renovation. At the request of his client, the textile industrialist Josep Batlló Casanovas, Gaudí created a new basement and converted the first story into offices, the second story into the client’s residence, the third and fourth stories into rental apartments, and the fifth story into servants’ quarters.

A key feature of Gaudí’s renovation is the large atrium carved into the heart of the building, which allows light to enter through the skylight and air to circulate through vents beneath the fixed-glass windows facing the atrium. Positioned at the center of this atrium is an elevator with a stairway wrapped around it. Gaudí thus transformed the traditionally dim, back-of-house area into a bright, prominent space.

-

Casa Batlló, atrium (the ventilation slits are visible beneath the windows).

The second-story portion of the main avenue façade was refashioned with a large glass curtain wall. What I would like you to focus on here are the series of small ventilation slits incorporated along the bottom of the windows. Describable as small versions of musōmado [Japanese sliding-slat ventilation windows], these slits can be opened to allow airflow. Ventilation slits also accompany the windows facing the atrium. Gaudí thus treated the atrium as a semi-outdoor space and the rental apartments as “houses within a house”.

The dining room, which faces the terrace at the rear of the second story, also features large windows. These, too, were novel at the time. They are designed not only to allow one to enjoy meals in a sunlit room but also to seamlessly connect the interior with the outdoor terrace.

-

Casa Batlló, second-story dining room.

Gaudí employed a similar approach in the dining room of one of his earliest works, the Palau Güell (1889). Appropriate to the fact that his client, Eusebi Güell, was one of Barcelona’s wealthiest men, this house makes liberal use of marble sourced from Güell’s own quarry and is adorned with intricate wrought-iron ornamentation throughout. It also features splendid Gaudí-designed Venetian blinds outside the windows of the second-story dining room. The architect gave thorough consideration to ventilation in this house as well. Ventilation shafts leading up to the rooftop serve not only the basement carriage garage but also all the rooms above it. The most striking feature is the 17-meter-high atrium positioned at the center of the second story; its ceiling contains many small openings that allow air to escape outside. The bristling “chimneys” on the rooftop thus are not solely for fireplaces but also serve ventilation purposes.

The Casa Milà is another residential building Gaudí designed with careful attention to lighting and ventilation. Commissioned by Pere Milà i Camps (a businessman) and Roser Segimon i Artells (Pere’s wife and the landowner), the building stands on the former site of a church and is said to have been built by repurposing discarded bricks left on the site (the building’s primary structure is steel). Each story has four apartments, and every unit has been designed to allow light and air to be brought inside from both the outer façade and inner lightwells. With windows not only in the entrance halls and living rooms but even in the kitchens, utility rooms, and bathrooms, along with high ceilings, these living spaces feel truly bright and comfortable when you are inside.

-

Casa Milà, apartment entrance hall. -

Casa Milà, apartment kitchen.

The Casa Milà also has a large basement garage. It is precisely because of such amenity-focused, forward-thinking considerations that this apartment building remains a highly sought-after property even today, more than a century after its completion. The fact that its designer, Gaudí, was a “sensible architect” should deserve more recognition.

Hiroyasu Fujioka

Born 1949 in Hiroshima, Japan. Researcher of modern architectural history. Emeritus professor of the Tokyo Institute of Technology Graduate School of Science and Engineering. His focuses include research on architectural thought and design, such as the historical development of “Japanese-ness” and the concept of “space”, as well as biographical research on architects, modern building technology history, and preservation theory. He has also been involved in preservation efforts, producing reports that elucidate the architectural value of historic buildings. Notable publications include Hyōgensha Horiguchi Sutemi: Sōgō geijutsu no tankyū [The Artist Sutemi Horiguchi: A Quest for a Total Art] (Chuokoron Bijutsu Shuppan, 2009), Kindai kenchikushi [Modern Architectural History] (Morikita Publishing, 2011), Meiji Jingū no kenchiku: Nihon kindai wo shōchō suru kūkan [The Architecture of Meiji Shrine: A Space Symbolizing Modern Japan] (Kajima Institute Publishing, 2018), and Horiguchi Sutemi kenchikuronshū [The Architectural Theories of Sutemi Horiguchi] (author and editor; Iwanami Shoten, 2023). Awards include the Tokyo Institute of Technology’s Best Teacher Award in 2003, the Architectural Institute of Japan’s AIJ Prize (Research Theses Division) in 2011, the Architectural Association of Japan’s Architecture and Society Award in 2013, and the Japan Coast Guard Commandant’s Award in 2021.