Series Shoei Yoh: A Journey of Light

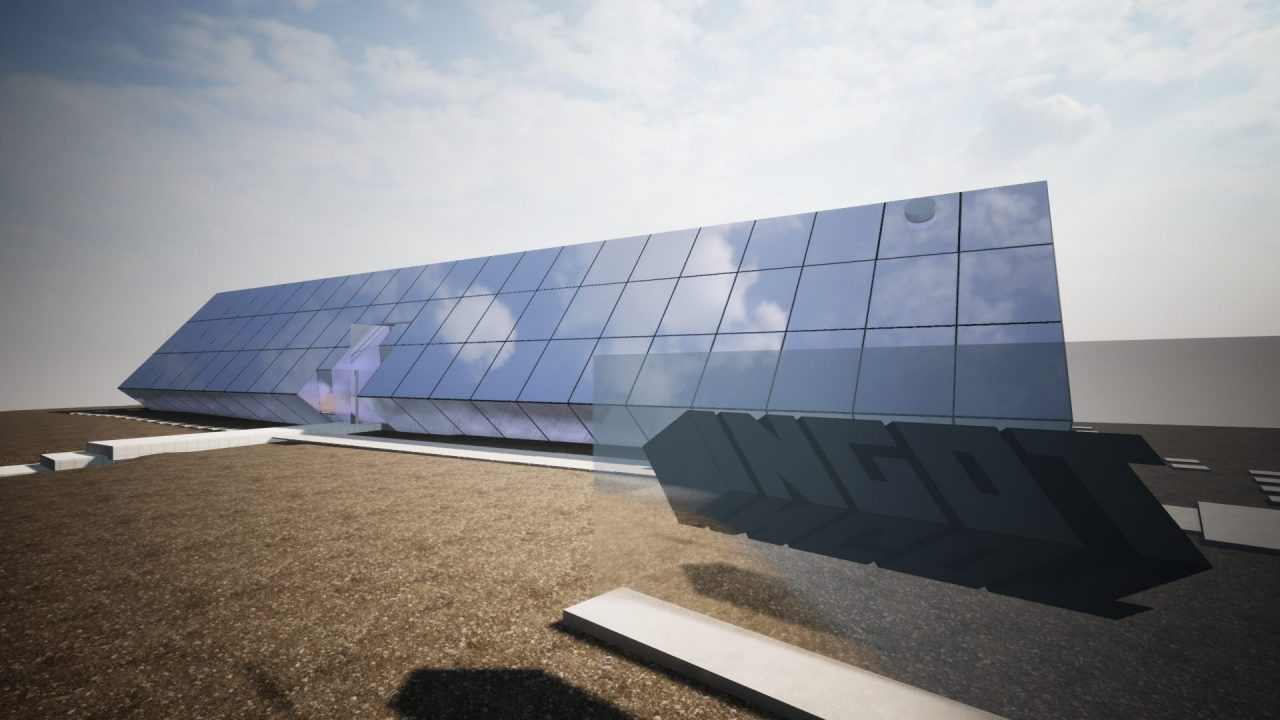

The Ingot Coffee Shop: Building as a Mass of Glass

04 Oct 2024

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Columns

- Essays

- Japan

Tomo Inoue, a building construction expert engaged in efforts to digitally reconstruct Shoei Yoh’s works using 3D scanners, explains the novelty of the Ingot Coffee Shop, an early work of architecture conceived as a “mass of glass”.

Glass Masses

The roots of glass architecture can be traced back to the Crystal Palace1 of 1851. This novel structure of iron and glass, the technical underpinnings of which were informed by Sir Joseph Paxton’s background as a gardener2, is considered a watershed work that marked the shift from buildings expressed as masses of masonry to those expressed as masses of glass.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Friedrichstrasse Office Building (1921) and Glass Skyscraper (1922) are also pivotal works of glass architecture. Although neither project was realized, Mies’ visions of the crystalline masses towering above the masonry streetscapes of Germany undeniably made a profound impression on many architects.

However, it would take another half-century before a building conceived as a mass of glass would materialize in reality. The moment finally came with the completion of the Willis Faber & Dumas Headquarters (1975) by Sir Norman Foster. There was also another such building that was realized at almost exactly the same time here in Japan: the Ingot Coffee Shop (1977) by Shoei Yoh.

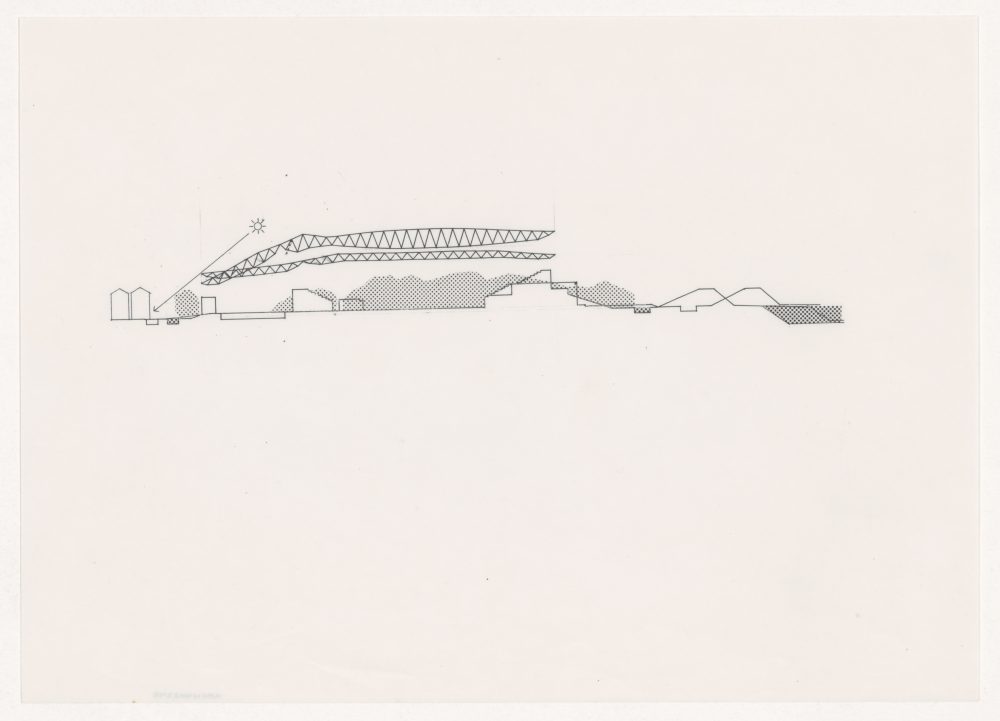

Born around the same time, the architects Foster and Yoh both spent their student years in the United States in the early 1960s, founded their practices in island nations in the fringes of Eurasia, and went on to produce many masterpieces. Foster’s Willis Faber & Dumas building is encased in black-tinted heat-absorbing glass3 assembled using the patch fitting system. Developed by Pilkington4, this glazing system can be described as the precursor to the DPG system5, where the glass is held in place mechanically. Yoh’s Ingot, on the other hand, was encased in heat-absorbing and heat-reflecting6 insulating glass7 assembled using the SSG system8, in which the glass is held in place chemically by the adhesive bonding strength of structural silicone sealant. Both the DPG and SSG systems were new glazing approaches that contributed to the spread of glass architecture from the 1990s onwards. While the fact that Foster and Yoh adopted these systems early to realize “glass mass” buildings may simply be explained as a matter of contemporaneity, the synchronicity of their careers is quite intriguing.

-

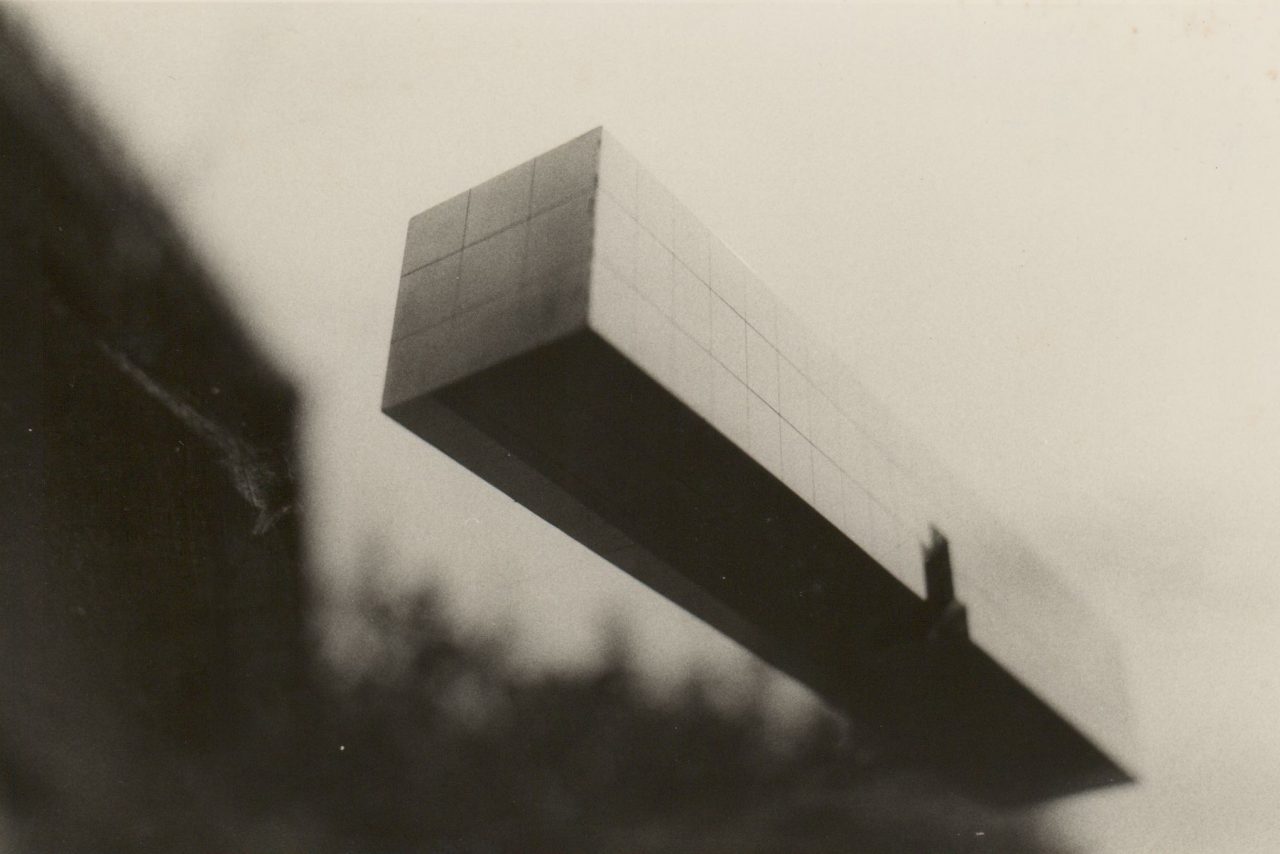

Ingot Coffee Shop, model view. Circa 1980. Shoei Yoh Archive, Kyushu University.

The word “ingot” technically refers to a mass of cast metal shaped for ease of use. While seemingly incongruous for describing a work of glass architecture, Yoh’s decision to use this term is understandable if one reads the building as a mass of glass. Here, I would like to delve into what made the Ingot an “ingot” while drawing from the digital reconstruction that we developed to better understand the now-demolished building.

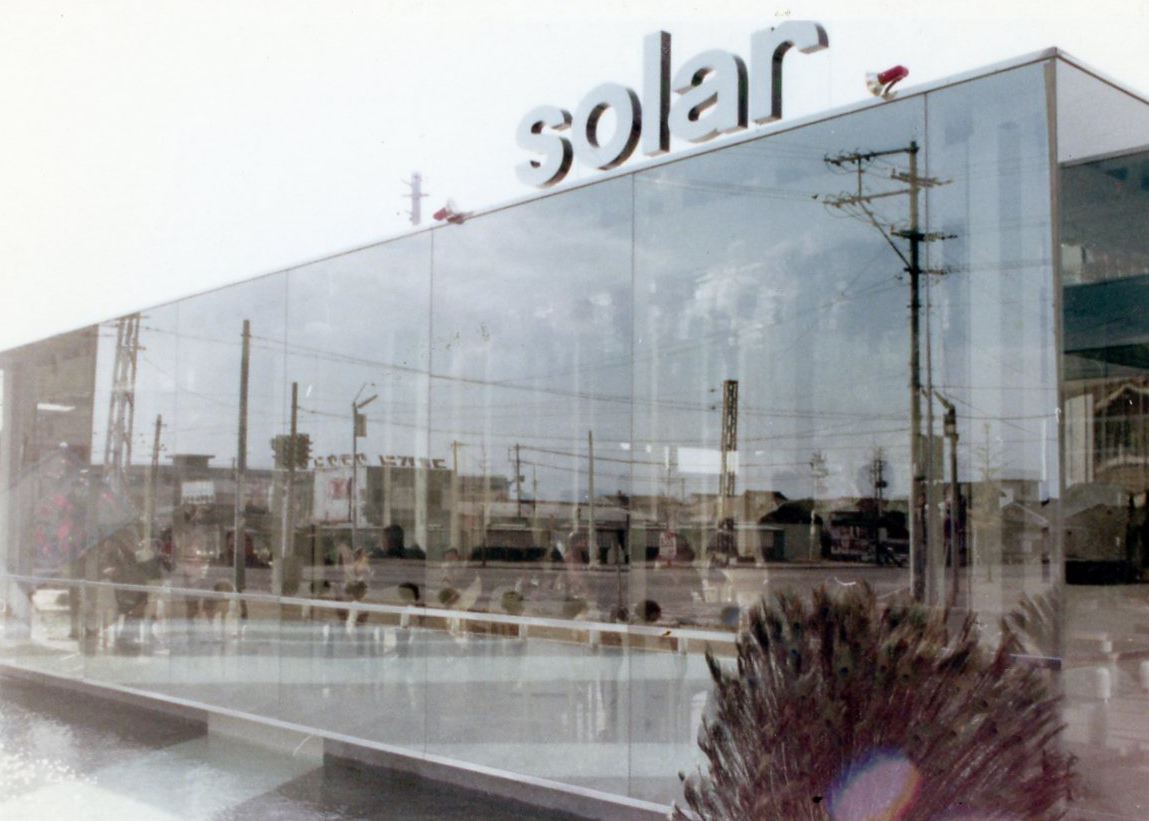

Pre-Ingot, Post-Ingot

Shoei Yoh started out on his own in 1970 when he founded his design firm in Fukuoka at the age of 30. His first independent project was the Café Solar & Air Service (1970) in Oita. Two features he experimented with in this project set the tone for the distinctive style he would go on to develop: the SSG system and light-emitting furniture (specifically, tables). The Café Solar can thus be considered the origin of his later Architecture of Light series and Luminous Furniture pieces.

At the time of this project, the SSG system, a still-new 1960s American invention, had yet to be implemented in Japan. This is what Yoh sought to accomplish at the Café Solar. The SSG system can be considered an offshoot of the glass mullion system. In the latter, the weight of the glass is supported mechanically from below by the lower frame member, while the wind loads are transmitted to the lower and upper frame members and to the glass mullions chemically by means of structural silicone sealant. This system is still commonly employed today in places such as automobile showrooms. The SSG system evolved from it when the glass mullions were replaced with metal ones. The late 1960s saw the emergence of two-sided SSG9 for curtain walls, and in 1971, the world’s-first instance of four-sided SSG10, where even the weight of the glass is carried by the silicone sealant, was realized in the US. This was the global technological backdrop against which Yoh attempted the SSG system for the first time in Japan at the Café Solar. However, due to technical concerns about the sealant’s ability to fully support the glass under extreme conditions such as earthquakes and gales, he ultimately settled on using two-sided SSG. The disappointment of not being able to realize four-sided SSG led him to reattempt it in the Yoh House Extension (1976), and he achieved it using triple-laminated structural glass, if only on the roof. The four-sided SSG that he realized at the Ingot the following year thus was a long-awaited accomplishment for him. Considering that the world’s first four-sided SSG was realized in 1971, had Yoh succeeded with his first attempt at the Café Solar, he could have added another achievement to his name as the pioneer of four-sided SSG.

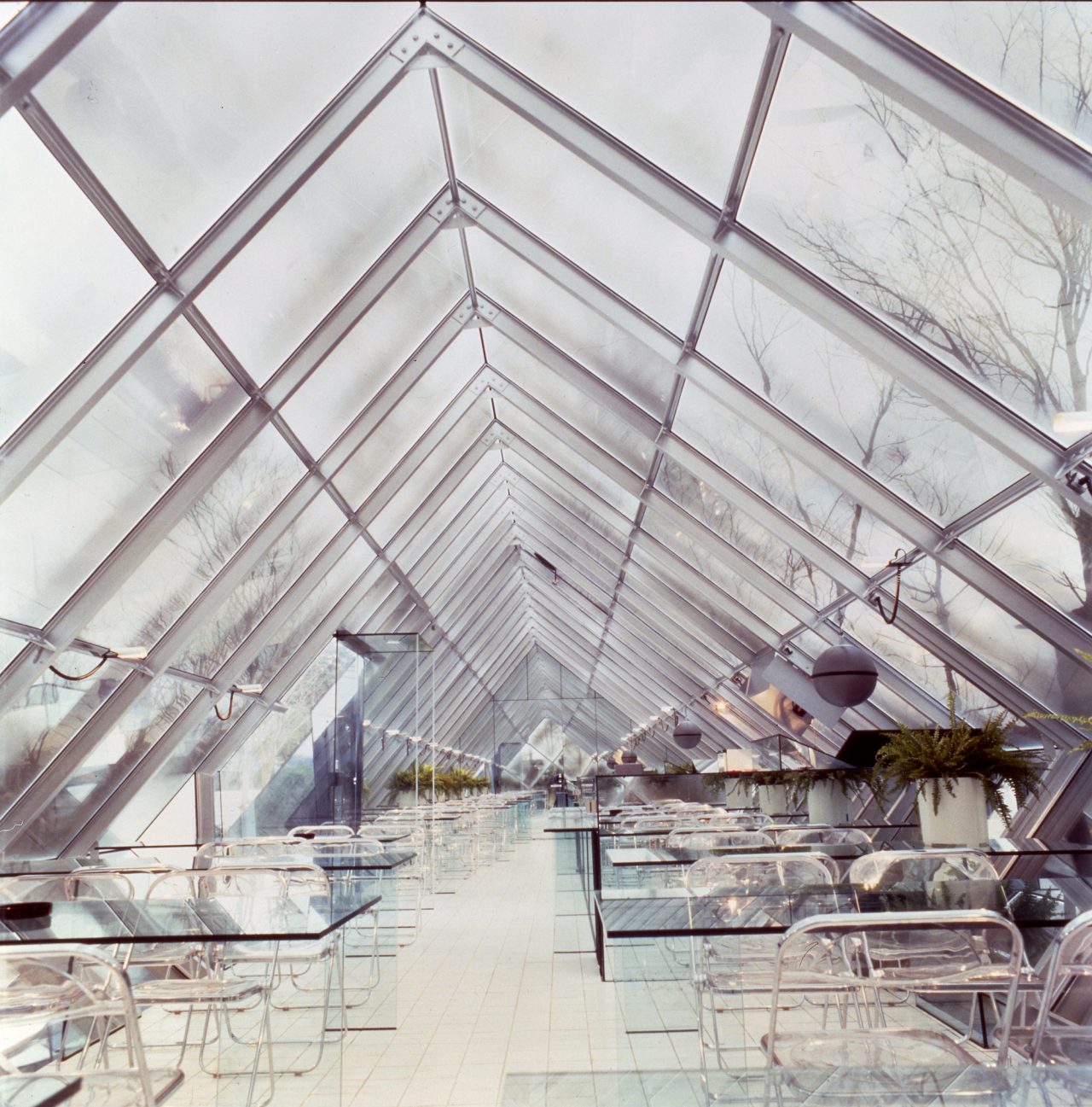

As for the light-emitting furniture pieces: these he continued to develop through several interior design projects. After producing the Luminous Furniture, Lighting Tube, and Wireless Lamp pieces, he arrived at the concept of “luminous gravity conversion”, whereby he manipulates the perceived lightness or heaviness of objects by “designing” the light and shadows, playing with how shadowless objects appear weightless while intense shadows augment light. The Ingot represents the epitome of this concept. During the day, the glass-encased steel-frame rectangular prism presented itself as a heavy mass of metal due to its silvery reflective glass11. At sunset, it became transparent as the glass seemed to vanish, melting away the distinction between inside and outside. Then, at night, it transformed into a weightlessness luminous mass by giving off light.

Yoh took a liking to the chemical-based glazing approach of using structural silicone sealant and employed it for various joints. For example, he used it to set the skylight glass at the Kinoshita Clinic (1979), Stainless Steel House with Light Lattice (1980), and Silver Building (1981). He even developed a method of using the silicone sealant to make weather seals for the Yoh House Extension, where he applied the sealant to three edges of the glass while using metal hinges on the remaining edge, and trimmed the sealant down after it hardened. Building on this further, he developed another method for the Kinoshita Clinic and House with Wind Lattice (1983), where he applied the sealant to all four edges of the glass, using it to create weather seals along three of the edges and a chemical hinge along the remaining edge. This is telling of just how much Yoh trusted this new way of creating joints with structural silicone sealant. When developing these original methods, he consistently worked with the same contractor to build a reliable relationship and diligently conducted durability and deformation recovery tests on the sealant.

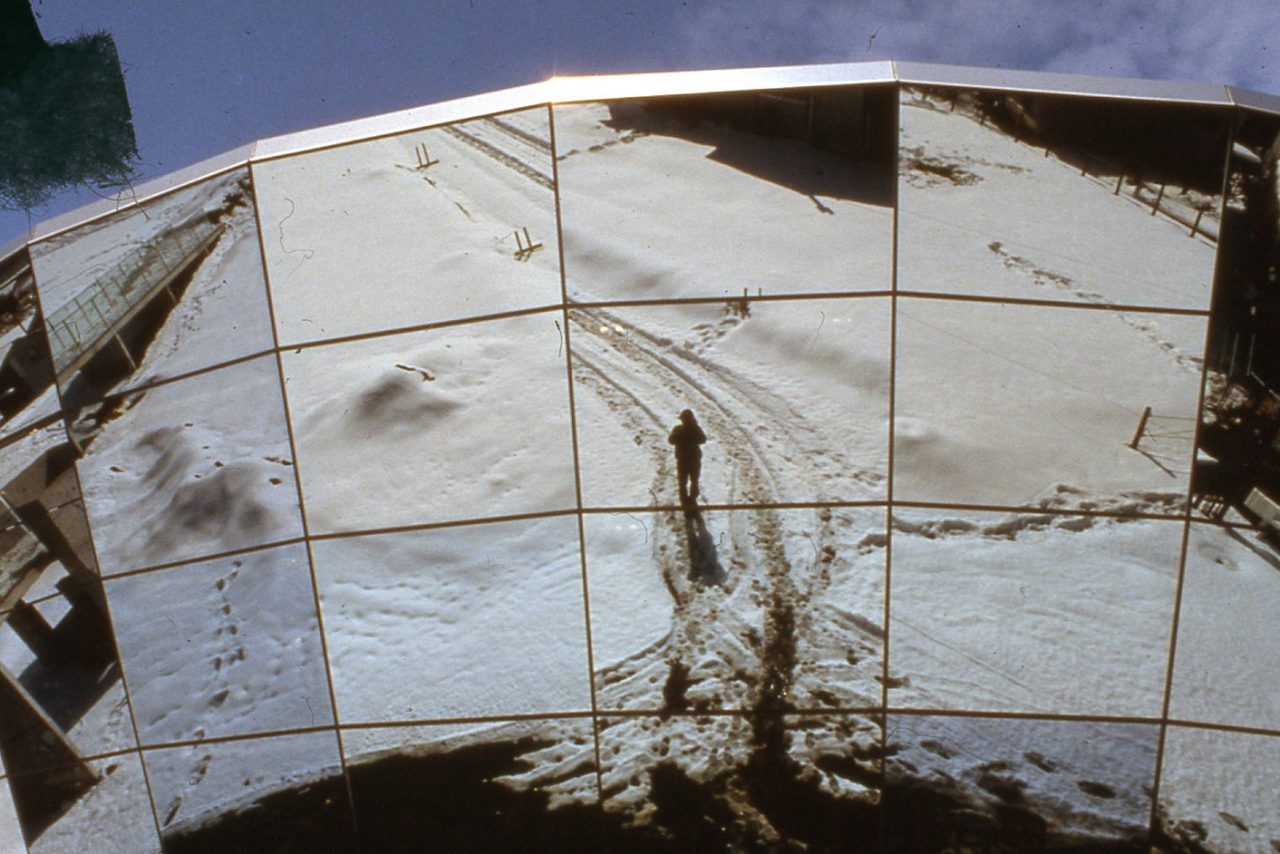

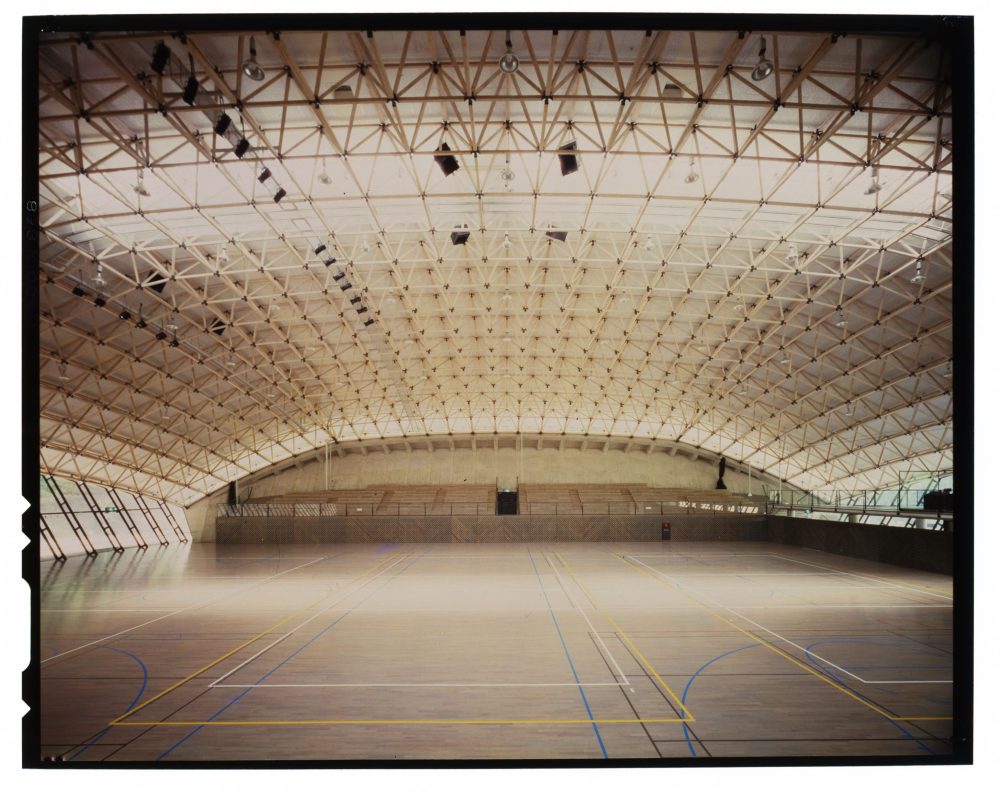

Yoh’s experimentations with four-sided SSG continued after the Ingot. He maintained his collaboration with the contractor that applied the structural silicone sealant at the Café Solar, Yoh House Extension, Ingot, and Stainless Steel House with Light Lattice until ACT6 (1985). At ACT6, he successfully realized four-sided SSG with insulating glass measuring 3 meters by 6 meters, fully constructed in situ. The panes are equipped with retainers to prevent them from falling out because the building’s characteristic façade leans towards the fronting road. Concerns about the durability of structural silicone sealant and the precautionary measures that could be taken in case it failed began to be heard around the time of this project, as other architects also started employing the SSG system. Yoh himself shifted to collaborating with more established glass manufacturers when working with the SSG system due to the growing size of his projects. For the four-sided SSG of the Oguni Bus Terminal (1987) and Saibu Gas Museum (1989), where the use of retainers was especially critical, he opted to have the glass fixed to the sashes with structural silicone sealant in a factory beforehand, rather than sealing them on site. Although Yoh personally had no doubts about the adhesive reliability of the sealant, the prevailing mood of the time left him with no choice but to have the glass pre-sealed in a factory for quality control and equipped with retainers.

-

Saibu Gas Museum. Photo: Kouji Okamoto. Shoei Yoh Archive, Kyushu University.

The SSG system, pioneered in Japan by Yoh, was adopted by many architects from the late 1980s to the early 1990s. However, the era of four-sided SSG soon came to an end due to factors such as the difficulty of achieving pure, smooth glass façades while including the required safety fittings, as well as the ambiguity surrounding liability in the event of an accident.

Digital Reconstruction

In 1986, just nine years after its completion, the Ingot was demolished to make way for road expansion works. Despite the nearly four decades that have since passed, its novelty still remains intact to this day. While we can no longer experience the actual building, we can have a simulated experience of it within the virtual realm of a computer.

Using BIM software, we constructed a digital 3D model of the Ingot based on the design documents and photographs of the building retained in the Shoei Yoh Archive at Kyushu University. When discrepancies were found between the drawings and photographs, of which there were many, priority was given to the photographs. For details that were unclear from the archival materials, such as the glazing joints around the entrance, we sought assistance from people involved with the project.

The digital reconstruction has been uploaded to Sketchfab, so I urge everyone to experience the “glass mass” that is the Ingot.

Notes

1:A pavilion built for the first World’s Fair, held at London’s Hyde Park in 1851. The enormous iron and glass building is also considered a forerunner of prefabricated architecture.

2:Sir Joseph Paxton (1803–1865) was an English gardener, architect, and politician. He designed numerous greenhouses and constructed the Crystal Palace on the commission of Prince Albert.

3:Made by adding a small amount of metal to its raw materials, this type of glass absorbs electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths longer than visible light (i.e., infrared radiation). By reducing the amount of solar radiation that enters the building, it enhances the effectiveness of the cooling system.

4:A glass manufacturer founded in nineteenth-century England. It is known as one of Europe’s leading glass manufacturers alongside France’s Saint-Gobain. In the 1950s, it developed the float glass process, a method for continuously producing flat sheets of glass by floating molten glass on a bed of molten tin. The company became a subsidiary of Nippon Sheet Glass in the twenty-first century.

5:Short for “dot point glazing”. A glazing system for realizing glass architecture in which strengthened glass is secured using holes in the glass itself, eliminating the need for sashes. The absence of externally visible sashes and other supports allows for the creation of highly transparent façades.

6:Made by applying a thin metallic coat to the surface of heat-absorbing glass, this type of glass also reflects infrared radiation, thereby reducing the amount of solar radiation that enters the building and enhancing the effectiveness of the cooling system even further.

7:Glass composed of multiple panes separated by air barriers to enhance thermal insulation performance, addressing one of the inherent weaknesses of glass.

8:Short for “structural silicone glazing”. A glazing system for realizing glass architecture in which the glass is adhesively bonded to its supporting elements using structural silicone sealant. The absence of externally visible sashes and other supports allows for the creation of buildings that appear as highly transparent masses of glass.

9:A glazing method where the glass is secured chemically with structural silicone sealant on two of its four edges, while the remaining two edges are supported mechanically by framing members, such as sashes.

10:A glazing method where all four edges of the glass are secured with structural silicone sealant.

11:Made by applying a thin metallic coating to its surface, this type of glass reflects infrared radiation, thereby reducing the amount of solar radiation that enters the building and enhancing the effectiveness of the cooling system.

Top image: Ingot Coffee Shop, twilight view. Photo: Shinkenchiku-Sha. Shoei Yoh Archive, Kyushu University.

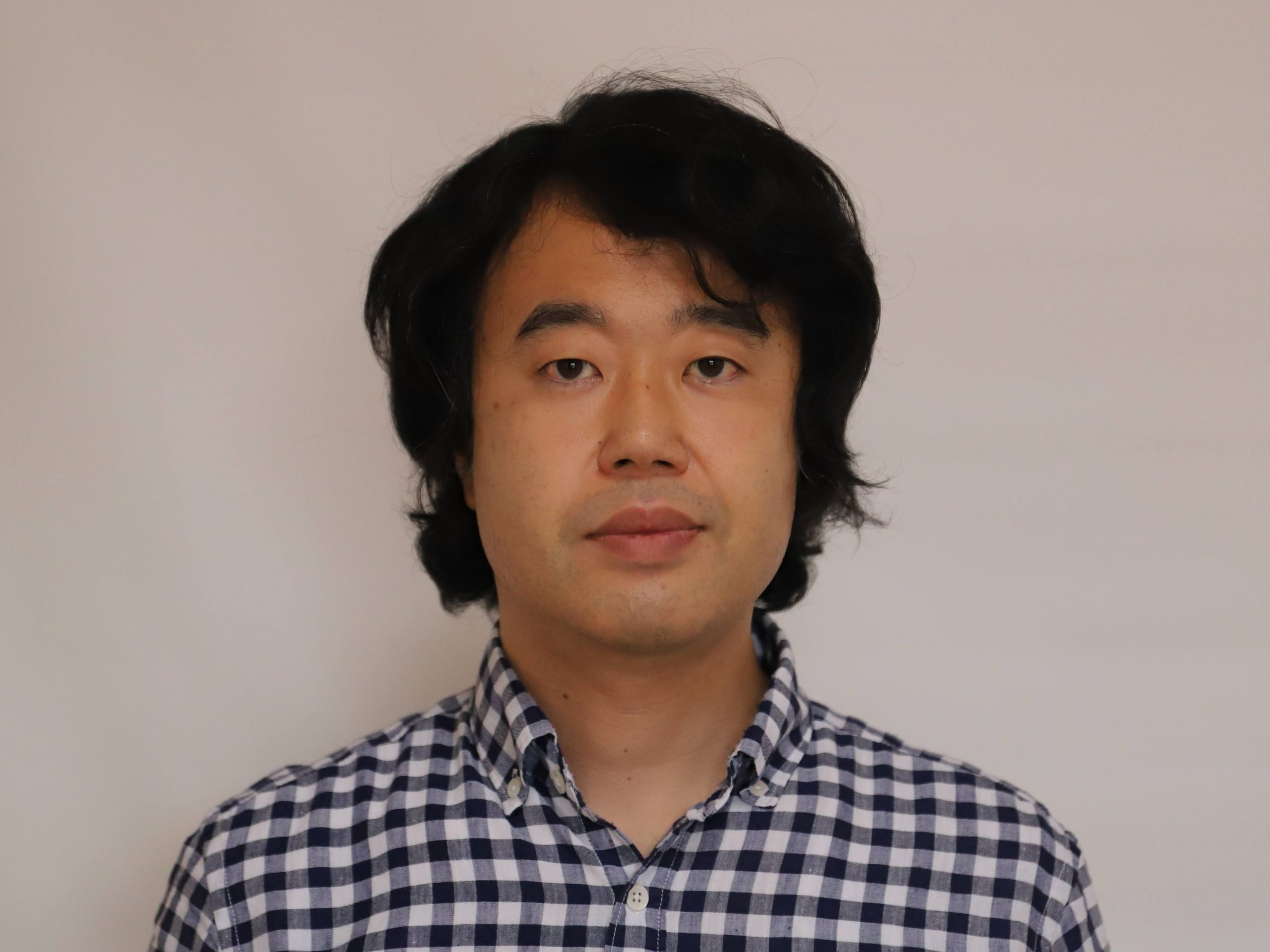

Tomo Inoue

Associate Professor, Faculty of Design, Kyushu University. Director, Environmental Design Global Hub (eghub). Completed a master’s degree in architecture at The University of Tokyo. Previously held positions as a research associate and associate professor at Kyushu University. Specializing in building construction and building production, his research focuses on how buildings work, are made, and are used. In addition to his work with digital archiving and digital reconstruction at the Kyushu University Shoei Yoh Archive, he is also engaged in digitally archiving Yoshichika Uchida’s buildings in Kyushu. As Director of the eghub, he is focused on developing collaborative research and educational partnerships with international universities. He is also involved in projects to date vernacular architecture from the British colonial era through “steel-beam archaeology” and to develop an archive of drawings of the Assam Bengal Railway.