Series Study on Hashirama-Sochi; Equipment In Between

Movie “Transition of Kikugetsutei”

28 Oct 2015

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Essays

- History

- Videos

movie "Transition of Kikugetsutei"

Kikugetsutei is a teahouse located in the early modern-age daimyo (feudal lord) garden “Ritsurin Garden”, in Takamatsu city, Kagawa Prefecture, Japan. The building was used for having tea or banquets, and was made in “shiho shoumen dukuri”, or designed in such a way that all four sides are designed as the front facade. Today, Kikugetsutei is open to the public, and visitors can enjoy green tea and teacakes, while admiring the open vista of the garden from inside. Kikugetsutei was built during the early modern age when daimyo gardens were flourishing, though the year of completion is unknown. It was crafted with great skill as a place for entertainment in the garden.

“Hashirama equipment” is a term used for cultural assets and refers to the entire architectural components between pillars. Specifically, the hashirama equipment includes a variety of types of fittings such as walls, shoji and fusuma sliding doors. In buildings with a wooden framework, in addition to the fittings, the boards and tatami mats on the floor and the ceilings are also basically composed of the similar “equipment-style” thoughts. Richness of space in Japanese architecture has been created by the diversity of the hashirama equipment. In this study, a building from Japanese architectural history is examined based on a key concept of the previously stated “hashirama equipment”.

As basic information, a variety of documents were investigated and edited. With the basic information, measurements were made and our own examinations were conducted of the hashirama equipment, and related figures were drawn. Furthermore, a short movie “Transition of Kikugetsutei” was made, based on our examinations.

Waseda University Norihito Nakatani Laboratory, Windowology: Cultural Magazine of Hashirama equipment

Principal researcher, Norihito Nakatani

Text content -Transition of Kikugetsutei-

<About Ritsurin Garden>

<The paths of former days>

<Hashirama and the hashirama equipment>

<Development of wooden shutters and a mechanism for rotating shutters>

About Ritsurin Garden

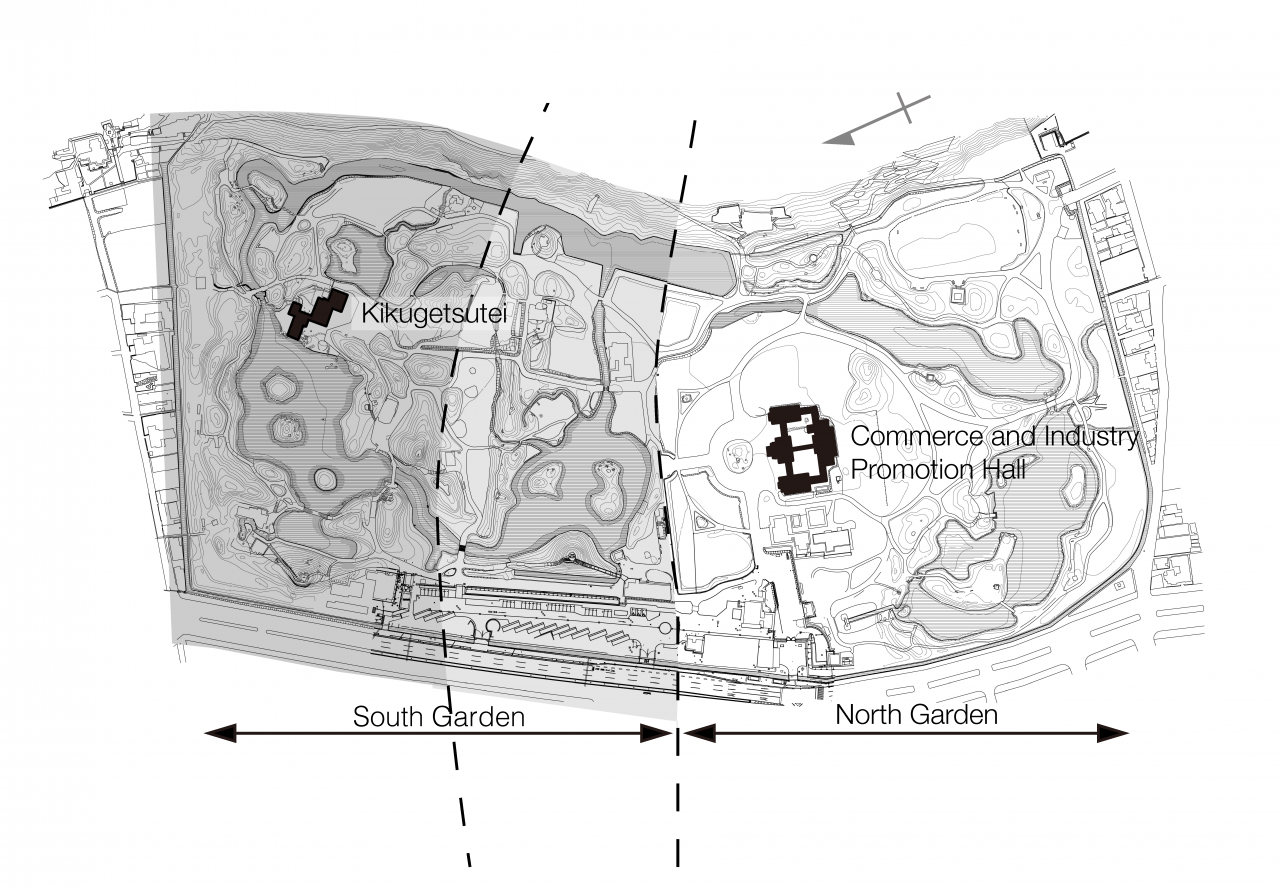

Ritsurin Garden is a traditional strolling-style daimyo garden located in Takamatsu city, Kagawa Prefecture. It is designated as a Special Place of Scenic Beauty of Japan. One theory suggests that the name of the garden, “Ritsurin” (the Chinese character for which means “chestnut tree woodland”), was derived from the chestnut trees planted. The specific establishment year of Ritsurin Garden is unknown. However, the site was already utilized by a local ruling family, Sato, before 1587 when the Ikoma Family, who had successively ruled the Takamatsu Domain, became the feudal lord. The currently existing garden around Nanko pond, located on the southern side of Ritsurin Garden, is said to have been built during the time of the Ikoma Family (i).

Records remain that show the garden was made during the time of the fourth lord of the Ikoma Family, Takatoshi. Later in 1642, a new ruler, the Matsudaira Family, took over the Takamatsu Domain in Sanuki Province and inherited the garden as a villa. It is thought that the Matsudaira Family did not have enough time to create a new garden, and used Ikoma’s existing garden for the villa (ii). The north side of the garden was expanded by the time of the second lord, Yoritsune Matsudaira. Apart from Kikugetsutei, Hinoki-goten (literally meaning “cypress palace”) was built as a residence around the same time. Hinoki-goten was later demolished and cannot be seen today. The garden was renovated in the name of remedial actions for farmers at times of drought or crop failure: the farmers worked at renovating the buildings or constructing the garden, and the lord provided them with rice as a wage. For more than 100 years from the time of the Ikoma Family until the Matsudaira Family, the garden was gradually built/renovated starting from the Nanko pond side until it was completed at its current size. The garden is among the largest of the gardens designated as national sites of scenic beauty.

In order to open the Ritsurin Garden as a public park in the Meiji Period, the Kagawa Prefectural Museum (currently the Commerce and Industry Promotion Hall) was built at the former Hinoki-goten site in 1899. The garden, unmanaged since the end of the Edo Period when the feudal system was demolished, was also redeveloped and became closer to the current garden condition. The south garden still preserves the past condition as a superb stroll garden, even after redevelopment.

-

Ritsurin Garden Layout Plan

i From Special Place of Scenic Beauty Ritsurin Garden Kikugetsutei Conservation and Repair Works Report (Kagawa Prefecture, 1994). The rest of the study also referenced this document.

ii From “Historical Study of Ritsurin-so” by Shoichi Matsuura who was a cultural expert advisor of Kagawa Prefecture for the above report.

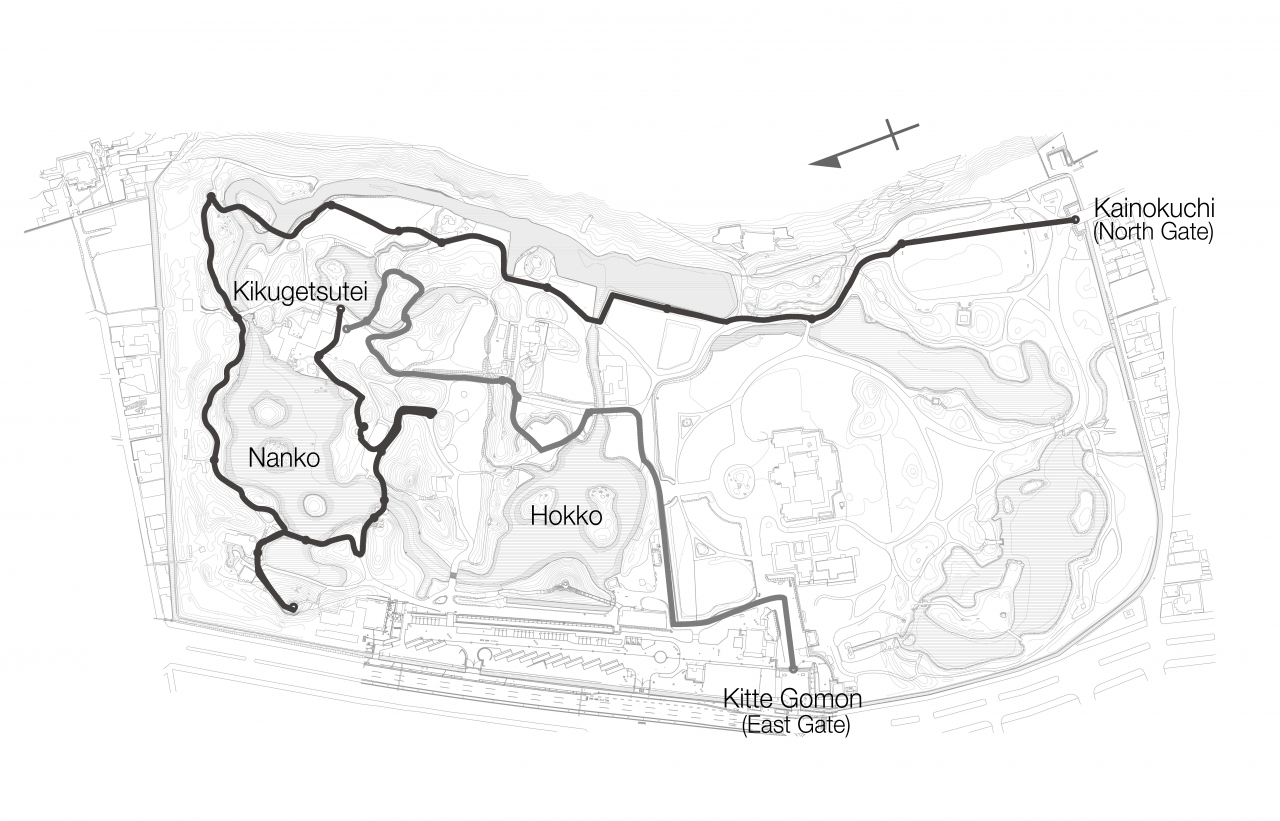

The paths of former days

The stroll garden of the modern age is referred to as “ippo ikkei” (literally meaning ‘One step, One scene’), with a characteristically wide variety of garden views that unfold at each step. The walking paths of the former domain lords can be inferred from the order of viewing spots in the garden described in “Ritsurin-so Journal” (1745), which was written in classical Chinese by a Confucian scholar of the domain, Bunsuke Nakamura, during the time of the fifth lord Yoritaka Matsudaira. There were two entrances to Ritsurin Garden at that time: Kitte Gomon (current East Gate) and Kainokuchi (current North Gate). Kitte Gomon was for guests who had kitte, i.e., invitations, while Kainokuchi was for relatives to enter the garden. Each gate had its own path for strolling the garden, and the destinations of both paths were near Kikugetsutei.

Ritsurin Garden is a “strolling pond garden”, in which the ponds occupy the majority of the garden. The Following irrigation work in the Edo Period, the current course of the Koto River is away from Ritsurin Garden, and the pond water in the garden is supplied by groundwater from the south part of the garden. Takamatsu had often suffered from drought since the irrigation work, and many irrigation ponds were made in the area as a countermeasure. With its abundant water, Ritsurin Garden was usually used as daimyo garden for entertaining guests and the lord himself, while the pond water also served as a water source in times of drought.

-

Paths

-

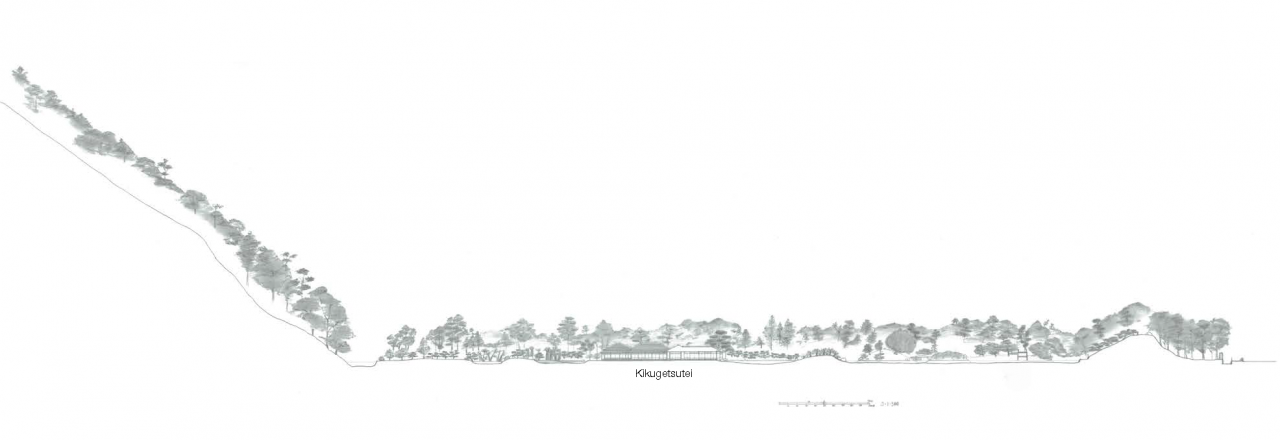

Ritsurin Garden, South Garden side section

Hashirama and the hashirama equipment

In masonry constructions that were built in Western civilizations, small openings were made as if digging a hole, since the entire walls supported loads. Conversely, in Japanese wooden buildings with a beam-column frame, openings could be made to fully utilize the space between pillars (hashirama), since the elements such as walls and fittings between the pillars do not affect the structure. How to utilize hashirama was one of the most important points to examine for Japanese buildings with a beam-column frame.

-

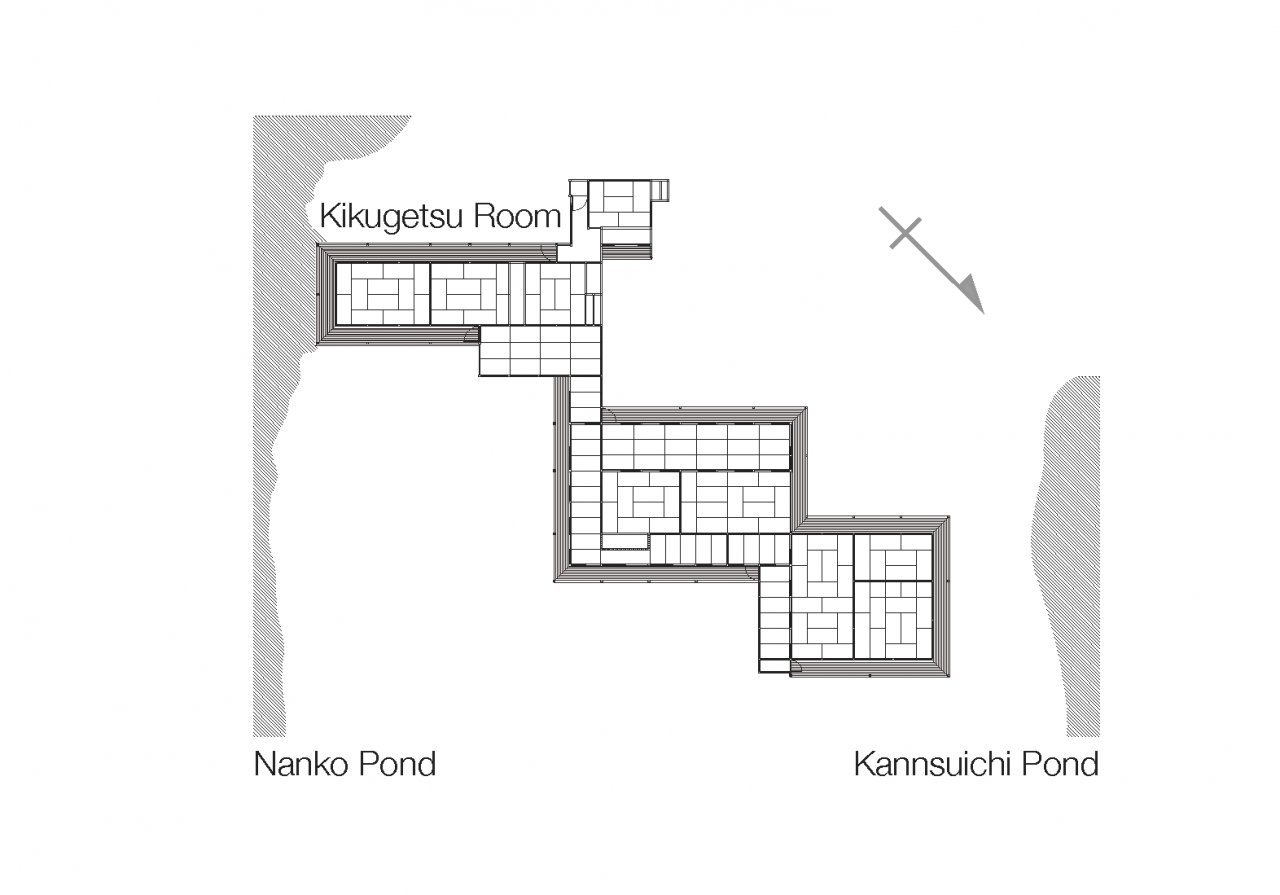

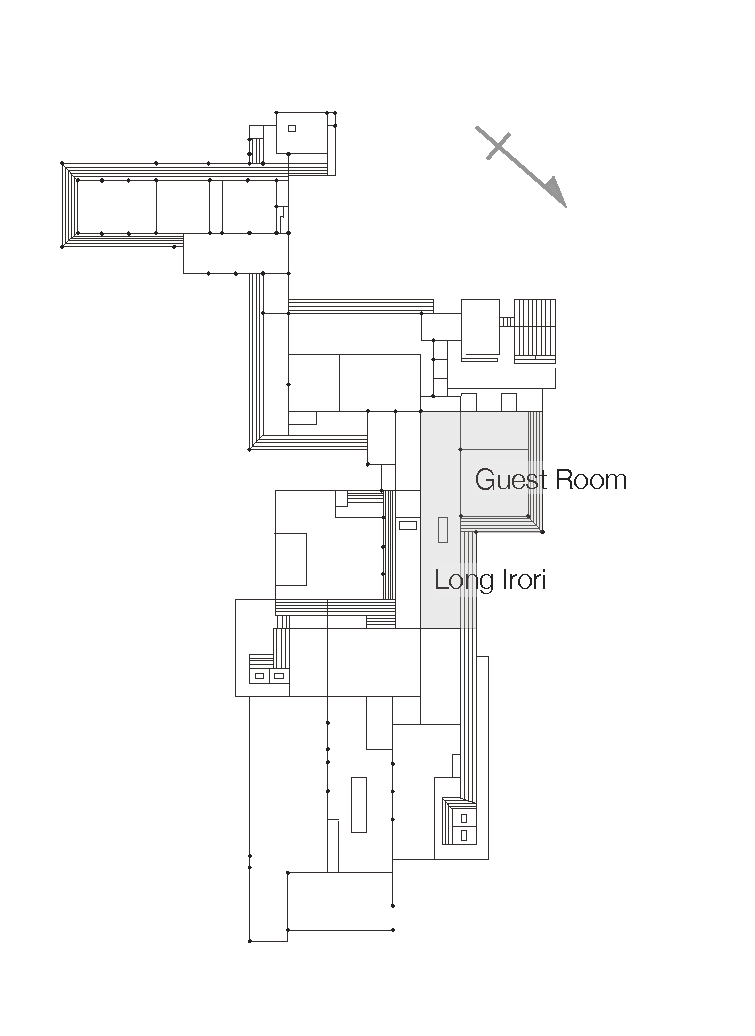

Current Kikugetsutei floor plan -

Old Kikugetsutei floor plan

For buildings in a daimyo garden, creation of comfortable spaces for a building used as a place for banquets and recreation was vital. In such buildings, an effective use of the hashirama equipment was important, such that it was versatile and could be opened, closed, or removed, rather than having walls. Not only in Kikugetsutei, but also in the teahouses and shoin (reception room) in the daimyo gardens of the early modern age, such as Okayama Korakuen and the Katsura Imperial Villa, the entire garden could be seen from inside when the fittings were opened. Elaborate ideas were used for enjoying the views from the building. The intention of the building equipment, and thus that of the hashirama equipment, can be inferred from the name of the building or poems written there. Furthermore, the fittings as the hashirama equipment were also visually effective, as well as effective in adjusting environmental aspects, including temperature, humidity, ventilation, and lighting. The transformation of the spaces due to the fittings is one of the biggest appeals of Japanese architecture, which is even better recognized in buildings in gardens.

-

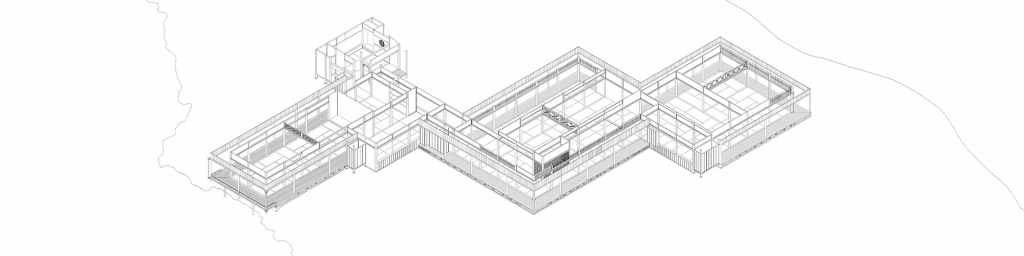

Kikugetsutei with opened shoji, fusuma, and wooden shutter

(Kikugetsutei isometric drawing I)

-

Kikugetsutei with closed shoji and fusuma, and opened wooden shutter

(Kikugetsutei isometric drawing II)

-

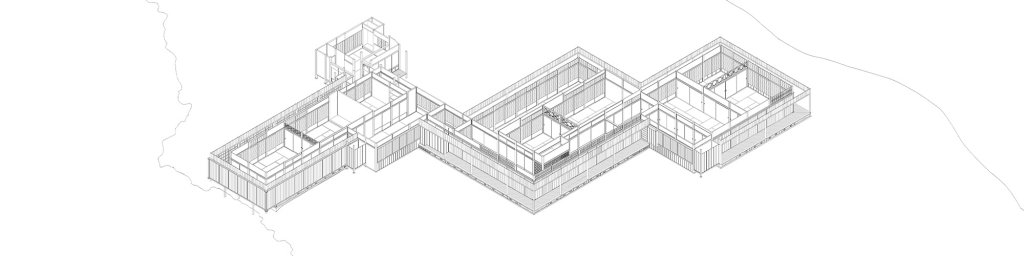

Kikugetsutei with closed wooden shutter

(Kikugetsutei isometric drawing III)

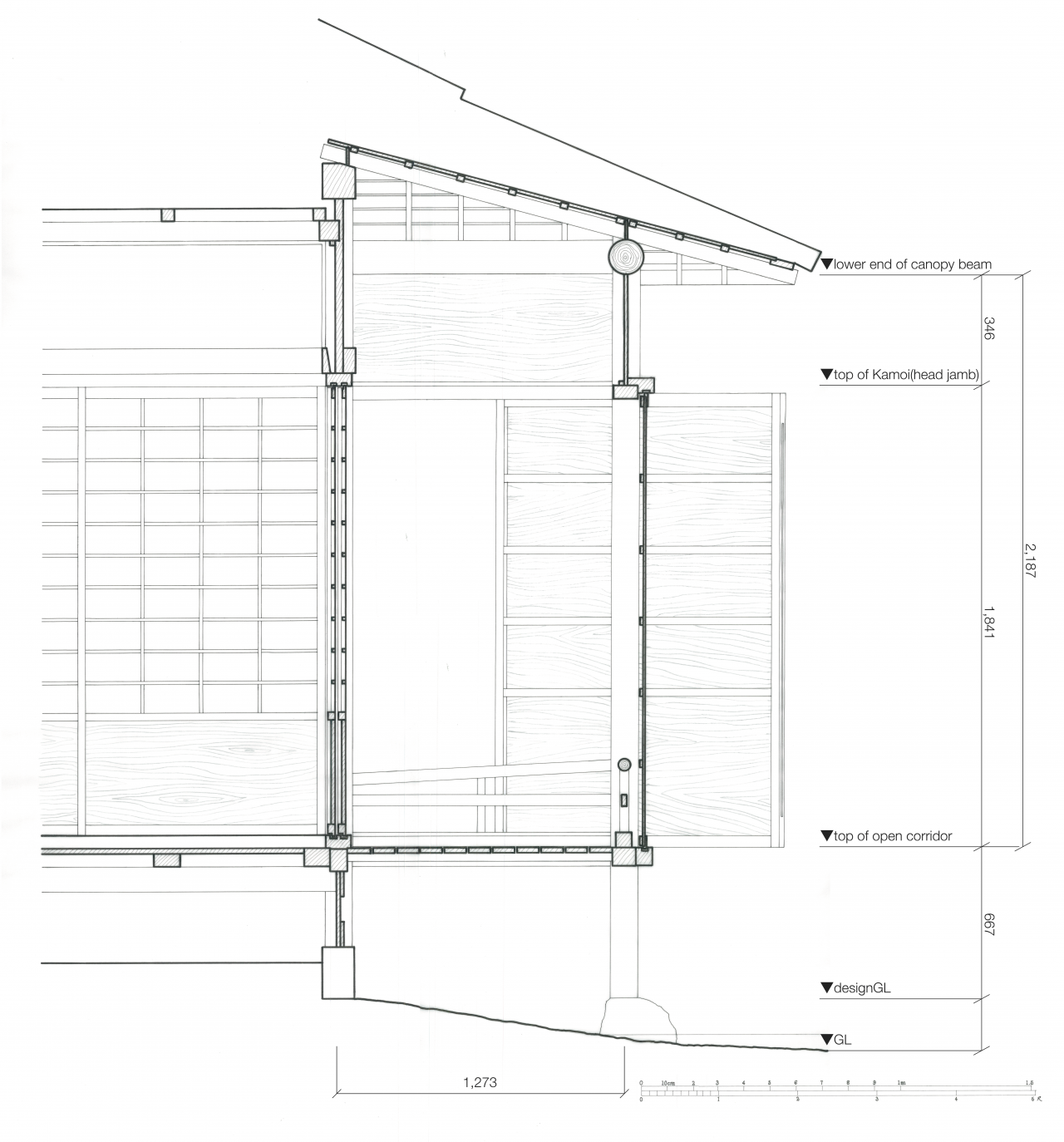

Development of wooden shutters and a mechanism for rotating shutters

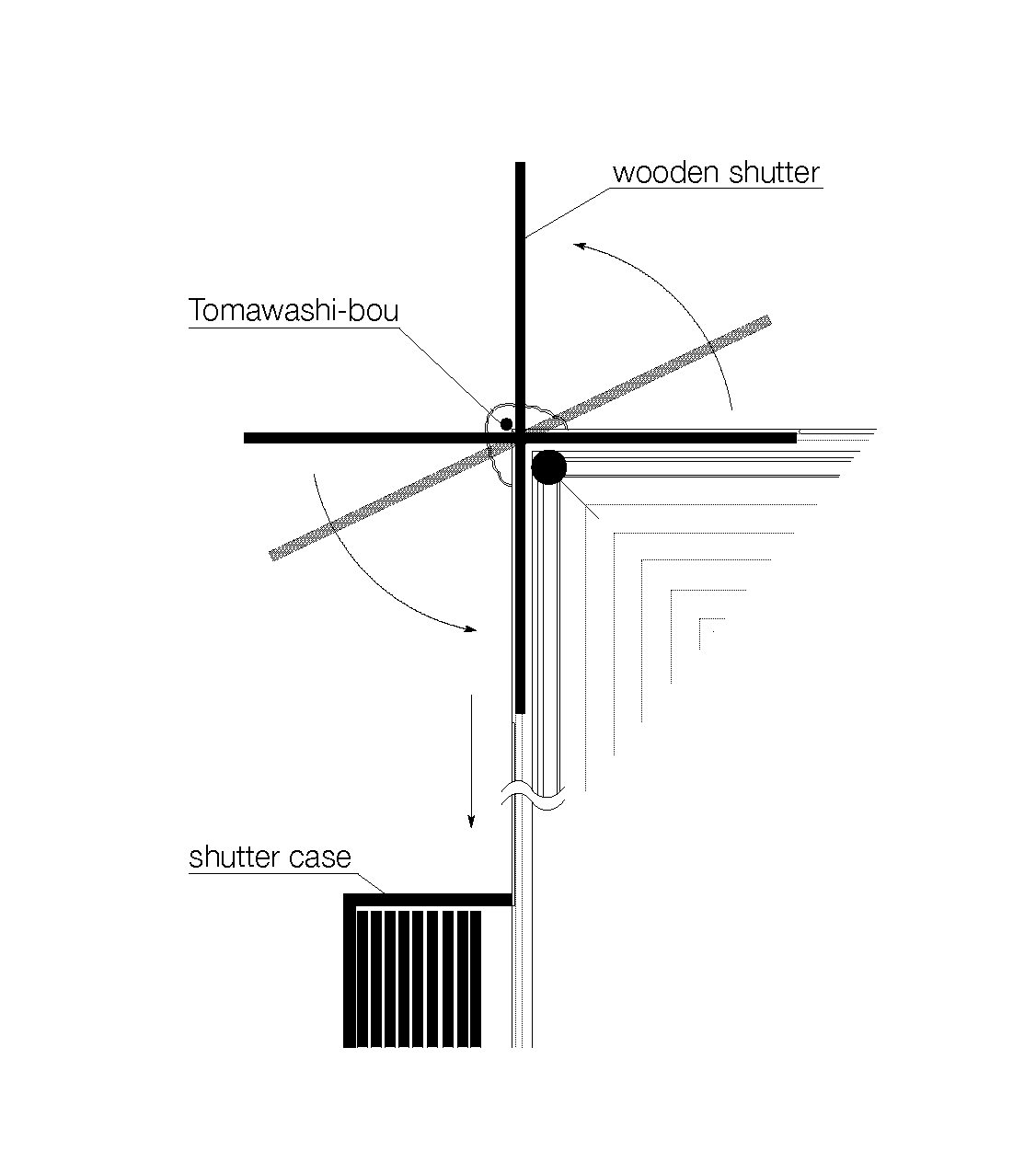

The origin of hashirama equipment with a function of shutters was wooden doors added to hashirama in order to protect shoji and fusuma sliding doors. Until the middle ages, three grooves were made in hashirama, which held a wooden sliding door, another wooden sliding door, and a shoji door, respectively (the order is from outward to inward). In this case, wooden sliding doors were left in hashirama, blocking half of the view even when the wooden doors were opened. In terms of sliding door details, sliding door grooves used to be engraved in rails between pillars, but at the dawn of the early modern age they were transformed into a single-channel shikii (threshold) and kamoi (head jamb) with sliding door grooves located outside of the pillar line and wooden shutters were installed there. This eliminated a limitation in the movable range of wooden shutters, which used to be only within hashirama, and the wooden shutters were stored in a wooden shutter case by moving them along a single groove. According to an architectural historian, Kiyoshi Hirai, this change occurred around 1600, and examples can be found in an old drawing of the hall of the Nagoya Castle Honmaru Palace, as well as in the remains of the hall of the Nijo Castle Ninomaru Palace. Furthermore, in the New Palace of Katsura Imperial Villa, built in the mid-17th century, irikawa-en, or a interior veranda between the building and the exterior veranda was developed, where lines for the wooden shutters and shoji doors were placed on the outside of the exterior veranda. As a result, the spaces in Japanese architecture were even more diversified.

In the New Palace, the wooden shutters can be rotated at the corners of the building by using a mechanism called “amado-mawashi” (literally meaning “wooden shutter rotator”). When opening the wooden shutters, each wooden shutter slides in a special groove towards the corner. At the corner, the door groove is shortened by a half width of the door from the end, so that the half of the door is free of the groove and it can rotate around the amado-mawashi by 90 degrees in the groove-free area, consequently sliding onto the door groove on the perpendicular side. Amado-mawashi helps to hold the wooden shutter inwards, preventing it from falling into the garden or pond, while supporting the rotation. The wooden shutter is rotated 90 degrees around the amado-mawashi, the supporting point, and enters into the next groove. By using this mechanism, only one shutter case was made, instead of four on the each corner of the building. This eliminated the wooden shutters from the sides facing the pond and garden, ensuring an open vista.

-

Mechanism of the wooden shutter

-

Detail of a cross section of open corridor of Kikugetsu Room

“Tomawashi-bou” or bars for rotating shutters in Kikugetsutei are thought to be an older version of amado-mawashi, which indicate that the main purpose of Kikugetsutei was for admiring the garden without any obstructions. The effect of amado-mawashi for this purpose was great.

Reference: Special Place of Scenic Beauty Ritsurin Garden Kikugetsutei Conservation and Repair Works Report (Kagawa Prefecture, 1994), Story of fittings by Yasuo Takahashi (Kajima Institute Publishing Co.,Ltd., 1985), and “A discussion on wooden shutters” by Kiyoshi Hirai Summaries of Technical Papers of Annual Convention of Architectural Institute of Japan Academic Conference (Tokai), 1976.

Norihito Nakatani: An architectural historian, professor of Waseda University, and the principal researcher of this study. His chief literary works include Revisiting Kon Wajiro’s ʻJapanese Houses’ (as part of the Rekiseikai group, Heibonsha, 2012), Severalness+: The Cycle of Things and Human Beings (Kajima Institute Publishing Co.,Ltd., 2011), and The Study of Classical Literature, the Meiji Period, and Architects (Ikki Shuppan, 1993).

Cooperation: Kagawa Prefecture, Special Place of Scenic Beauty Ritsurin Garden, Ryotei Nichou

* This article is extracted from “Cultural Magazine of Hashirama Equipment”, collaborative research with Norihito Nakatani Laboratory in Waseda University.