"Shoei Yoh: A Journey of Light" Symposium Report

7 SEP, 2024

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Talk Events

On September 7, 2024, the symposium “Shoei Yoh: A Journey of Light” was held at the AIJ Hall (Architectural Institute of Japan, Tokyo). Centered around the theme of “light”, this event was organized as part of an ongoing initiative, launched in 2019, to compile an archive for architect Shoei Yoh at Kyushu University (Fukuoka). The Window Research Institute (organizer) has been supporting the research activities of the Kyushu University Shoei Yoh Archive (co-organizer) as well as the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA, Montreal; supporter), which is also safeguarding a portion of Yoh’s archival materials in its collection.

The symposium’s program was divided into the two broad thematic sessions: “From Interiors to Non-Architecture” and “From Timber to Computation”. Each session featured individual presentations by the panel, which consisted primarily of faculty members from Kyushu University and the University of New South Wales (UNSW, Sydney; supporter), followed by a discussion.

The symposium coincided with Revisiting Shoei Yoh, an exhibition of Yoh’s archival materials from the Kyushu University collection held from September 3 to 8 at Shinkenchiku Shoten | Post Architecture Books (Tokyo), a bookshop co-founded by architecture publisher Shinkenchiku-Sha and art bookstore Post (Tokyo). Additionally, a seven-part essay series exploring the same themes as the symposium was published on this website leading up to the event. Together, they provided an opportunity for those in Tokyo to gain a comprehensive overview of the career of the Kyushu-based architect.

-

A message from Martien de Vletter, Associate Director of Collection at the CCA, was presented at the start.

Renewed Interest in Shoei Yoh

To open the symposium, Tomo Inoue (Kyushu University) presented Shoei Yoh’s biography and explained that there has been growing interest in reappraising Yoh’s work both domestically and internationally. For example, Yoh was featured in the CCA exhibition Archaeology of the Digital (2013) as a pioneer of digital design and was awarded the Gengo Matsui Special Award of the 2024 Japan Structural Design Awards.

Inoue then spoke about the events that led to the founding of the Kyushu University Shoei Yoh Archive (established 2019). It was in 2017 that Masaaki Iwamoto (Kyushu University) learned Yoh would be permanently vacating his office, and in 2018, just as Yoh was preparing to discard his work materials, the university approached him with the offer to safekeep them.

Inoue also introduced the digital preservation research that the Environmental Design Global Hub, an international researcher center at Kyushu University, has been conducting in collaboration with UNSW since 2019.

Inoue, who personally also has been involved in these joint efforts to archive Yoh’s work using digital technologies, presented a digital scan of Yoh’s Oguni Dome; a digital reconstruction of Yoh’s Ingot Coffee Shop, which was demolished just eight years after its completion; and a virtual exhibition space built with the Unity game engine to showcase these digital archival materials.

He noted that these efforts, which bring together physical materials with digital technologies, are exemplary of “the DX (digital transformation) of modern architectural archives”.

From Interiors to Non-Architecture

The first session, titled “From Interiors to Non-Architecture”, was moderated by Inoue and featured presentations by Iwamoto, Tracy Huang (UNSW), and Nicole Gardner (UNSW).

Iwamoto spoke about the great importance Yoh placed on “light”, tracing its role in Yoh’s interior designs from the early part of his career to his later work with architecture and computational design.

He suggested that Yoh, who was born in Kumamoto in 1940 but left Kyushu for Tokyo to study econometrics at Keio University, likely embraced the use of computers in his design work due to his early exposure to the power of mathematics and computing.

Yoh evidently transitioned from economics to design after being impressed by the Air France Tokyo Office designed by Charlotte Perriand. The experience led him to study design in the United States, and after returning home in 1964, he joined a firm and worked on numerous interior design projects domestically.

-

Scene from the first session. Pictured from left to right are Tomo Inoue, Nicole Gardner, Tracy Huang, and Masaaki Iwamoto.

It was explained that Yoh’s fascination with light began early on, as demonstrated by his frequent use of glass and light to emphasize products on display, and he preferred that the spaces he designed not stand out but instead disappear.

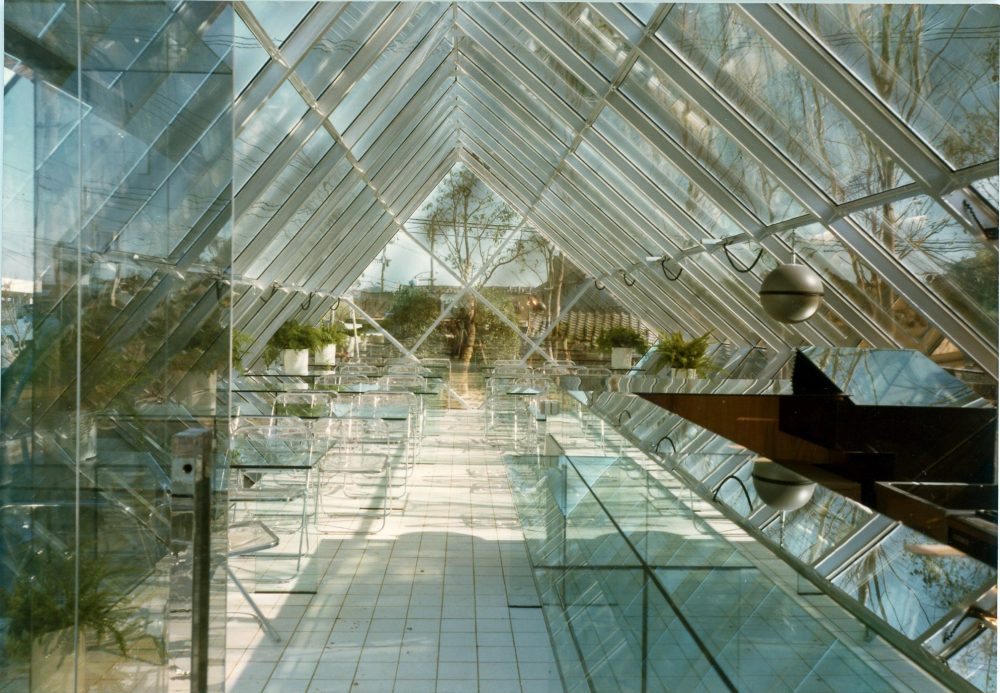

In 1970, Yoh established his firm in Fukuoka and completed the Café Terrasse Solar (1970), which is considered his debut work. In this project, he explored the two major concepts of “glass as a thin transparent membrane” and “luminous furniture”, through which he sought to emphasize the occupants and objects by creating furniture pieces that emitted light. These ideas led him to later discover the concepts of “luminous interiors” and “luminous gravity conversion”, where he created entire interiors that glowed with light and used light to manipulate perceptions of weight, respectively.

The focus of Yoh’s work gradually shifted from interiors to architecture in the late 1970s. With the Coffee Shop Ingot (1977), Japan’s first use case of four-sided structural silicone glazing, he created a building that visually transformed with the changing light. It was through this project that Yoh developed an interest in the idea of “architecture as a natural phenomenon”, and the keyword “non-architecture” also appeared for the first time in the text he presented with it. Relatedly, in the essay “Kenchiku kara no dasshutsu” [“Escape from Architecture”], which he published in a magazine after completing the Kinoshita Clinic (1979), he explains that his goal is to create “non-architecture” by incorporating design elements from outside the realm of architecture, such as windows from automobiles and aircraft.

-

Masaaki Iwamoto.

Iwamoto speculated that even after achieving a highly transparent space with the Ingot, Yoh was dissatisfied by the visibility of the building’s structure, and this drove him to later create the Stainless Steel House with Light Lattice (1981), where he visually erased the structural frame by constructing it in glass. Iwamoto concluded that this project embodies the idea of architecturalizing the ever-changing sunlight, marking a culmination of Yoh’s progression from interiors to non-architecture. Further details about Yoh’s career can be found in Iwamoto’s essay on this website.

Shoei Yoh’s Designs and Theories in Education

Huang’s presentation was about the relationship between Yoh’s design theories and practice. Yoh developed his own theoretical framework in the period from the start of his career, when he explored various ways of using artificial light-emitting objects and luminaires to create microscapes that evoke certain spatial experiences, through to the 1980s. Huang emphasized that Yoh’s design approach, while seemingly intuitive, was in fact grounded in theory and translated into practice. She also noted that Yoh’s theoretical framework has an affinity with the critical thinking-focused pedagogy employed at universities, offering an excellent example of how to bridge theory and practice.

Gardner, an architect and researcher specializing in computational design, followed by sharing her thoughts on Yoh from the perspective of digital technology and education.

She explained that Yoh’s project archive is used as an instructional resource for introducing first-year students at UNSW to parametric design and the historic development of computational design and sustainable biomimetic design.

-

Tracy Huang.

Education was also the theme of the panel discussion, during which the panelists were asked how Yoh might have approached his architectural studies if he were a student today, given the variety of advanced digital technologies now available.

Gardner hypothesized that since Yoh’s work is fundamentally centered on light, he likely would not have become a digital pioneer, instead allowing his exploratory spirit lead him in a broader range of directions.

Huang, noting that Yoh’s defining characteristic was not his rejection of the old or embrace of the new, but rather his ability to transcend norms and devise innovative solutions to address the challenges of his time, speculated that he would have leveraged various contemporary tools to experiment with even freer and more multifaceted approaches. She reemphasized that he would have actively adopted new technologies not as ends in themselves but as means to explore his ultimate interest: light.

-

Tomo Inoue (left) and Nicole Gardner (right).

The discussion covered a variety of other topics, including how Yoh’s use of locally sourced materials offers a reference for today’s students interested in sustainability, his international recognition as an interior designer, and the unique trajectory of his career from economics to interior design to architecture. During the Q&A session, the actively engaged audience posed numerous questions, sparking further discussion about how Yoh handled both artificial and natural light in a monistic manner, how Yoh honed his aesthetic sense, and how one might develop their aesthetic sense today.

From Timber to Computation

The second session, titled “From Timber to Computation”, shifted the focus to Yoh’s role as a pioneer of digital design, for which he is now being reacknowledged. The panel featured Koki Akiyoshi (Vuild), Yu Momoeda (Yu Momoeda Architects), who has been studying Yoh’s work since his student days and participated in the CCA’s archival research on Yoh, and K. Daniel Yu (UNSW), with Iwamoto serving as the moderator.

Momoeda began by presenting his interpretation of Yoh’s work through the lens of “architecture within motion”.

He suggested that Yoh perceived buildings as being detached from the earth and capable of being moved. He illustrated this point with the Coffee Shop Ingot, which Yoh envisioned as one of many “ingots crash-landing in various lands”, and also the Kinoshita Clinic, which dissociates itself from the ground and is aptly often referred to as a “UFO”.

-

Scene from the second session. Pictured from left to right are Masaaki Iwamoto, K. Daniel Yu, Koki Akiyoshi, and Yu Momoeda.

Through participating in the CCA’s “Find and Tell” project, in which various experts provide their interpretations of archival materials, Momoeda observed an evolution in Yoh’s work. Yoh explored the potential of creating structures that resonate with natural phenomena, initially through three-dimensional curved surfaces and later through continuously changing forms, which he could not achieve at the Oguni Dome. Accordingly, his designs transitioned from “crustaceans” to “galaxies” to “drifting clouds”, or in other words, from shelled structures to more free-flowing, organic, and weightless forms. This progression culminated in the Uchino Community Center for Seniors and Children (1995), which features an amorphous plan and the most organic of forms.

Momoeda suggested that Yoh was mindful of Frei Otto’s approach to form-finding and aimed to similarly create dynamic, organic, and lively works of architecture through combining experimental building methods with structures that resonate with the properties of the materials, allowing the materials to truly “perform”. Following the presentation, Iwamoto commented that Momoeda’s thesis aligns with that of the essay by Martien de Vletter (CCA), who writes that Yoh’s buildings are essentially about the roof.

Next, Akiyoshi spoke about the activities of his company, Vuild. He explained how he considers himself a “meta-architect”, as he engages not only in design but also in the development of materials and production systems. The various projects he presented included The Learning Architecture for Learners (2023), an educational incubation facility at Tokyo Gakugei University constructed using self-built stay-in-place concrete formwork.

-

Koki Akiyoshi.

Iwamoto remarked that the way Vuild leverages digital technology and involves itself in even the distribution side of architecture echoes Yoh’s approach. He particularly noted how their handling of the formwork at The Learning Architecture for Learners is very similar to Yoh’s use of bamboo formwork at the Naiju Community Center (1994), adding that he cannot think of any other works that share so many similarities.

Yu presented projects in which he utilized digital technologies and spoke about his interest in education that encourages innovation through the use of data across diverse scales, from buildings to cities. He also shared his various archival projects, including a 3D-prinatable, parametrically defined model of Yoh’s work and a digital reconstruction of the Naiju Community Center developed as a virtual exhibition space accessible online. Yu noted that Yoh, who understood how to generate geometric forms by inputting numbers and data, was far ahead of his time.

-

K. Daniel Yu.

Thinking from Construction

Iwamoto opened the panel discussion by addressing Momoeda’s presentation and asked the architects how they personally think about the relationship between their own work and metaphors, such as “crustaceans”, “galaxies”, and “drifting clouds”, with regard to the three aspects of “concept”, “material”, and “construction method”.

Momoeda explained that he tends to think about the concept first, followed by the materials, and then the construction method. He noted that this differed from Yoh’s design process for the Naiju Community Center, as he started not with a concept, but with a specific interest in exploring what kind of forms he could construct using concrete with bamboo formwork. Akiyoshi explained that he does not use metaphors when designing his projects, but instead starts with specific construction methods in mind and develops concepts from there. He described The Learning Architecture for Learners as an example of a project designed as an experiment with formwork.

-

Yu Momoeda.

Iwamoto followed by asking the panelists for their thoughts on Yoh’s architecture from the perspective of optimization and economic efficiency, which he cited as key reasons for employing computational design.

Momoeda pointed out that while economic rationality was indeed achieved through the use of computational tools with the Toyama Galaxy Hall (1992), the Naiju Community Center’s form was inherently irrational and was fundamentally shaped by a desire to design. This prompted Iwamoto to stress that an architect’s creative spirit should take precedence over concerns of economic efficiency by pointing to the example of Frank O. Gehry, who initially created the curved forms he envisioned using inexpensive materials, but later adopted 3D CAD technology from the aerospace industry to realize his curvilinear designs more rationally and economically, and eventually founded Gehry Technologies, which provides consultancy services to assist in creating even more complex buildings. Iwamoto reiterated that what distinguishes Yoh’s adoption of computational tools is that the exploration of light was his starting point.

Yu observed that while today’s parametric tools enable the creation of even more optimized designs than those achievable in Yoh’s time, no matter how much optimization is possible, someone must still ultimately decide on the final design. He argued that Yoh’s designs thus may not necessarily have been the most optimized solutions but were instead ultimately shaped by his aesthetic vision.

Akiyoshi pointed out that the notion that optimization leads to a “right solution” is flawed and that the general misconception that rectilinear designs are more economical is problematic. Emphasizing that the true strength of computational tools lies in their ability to process multiple variables simultaneously and to facilitate adjustments that satisfy all parties involved, he called for moving beyond the modernistic paradigm that thinks in terms of single variables. He then drew on the example of the concept of abduction being explored in the field of design studies to advocate that developing new design methods is crucial in architecture as well.

What Does Shoei Yoh Inspire in Us?

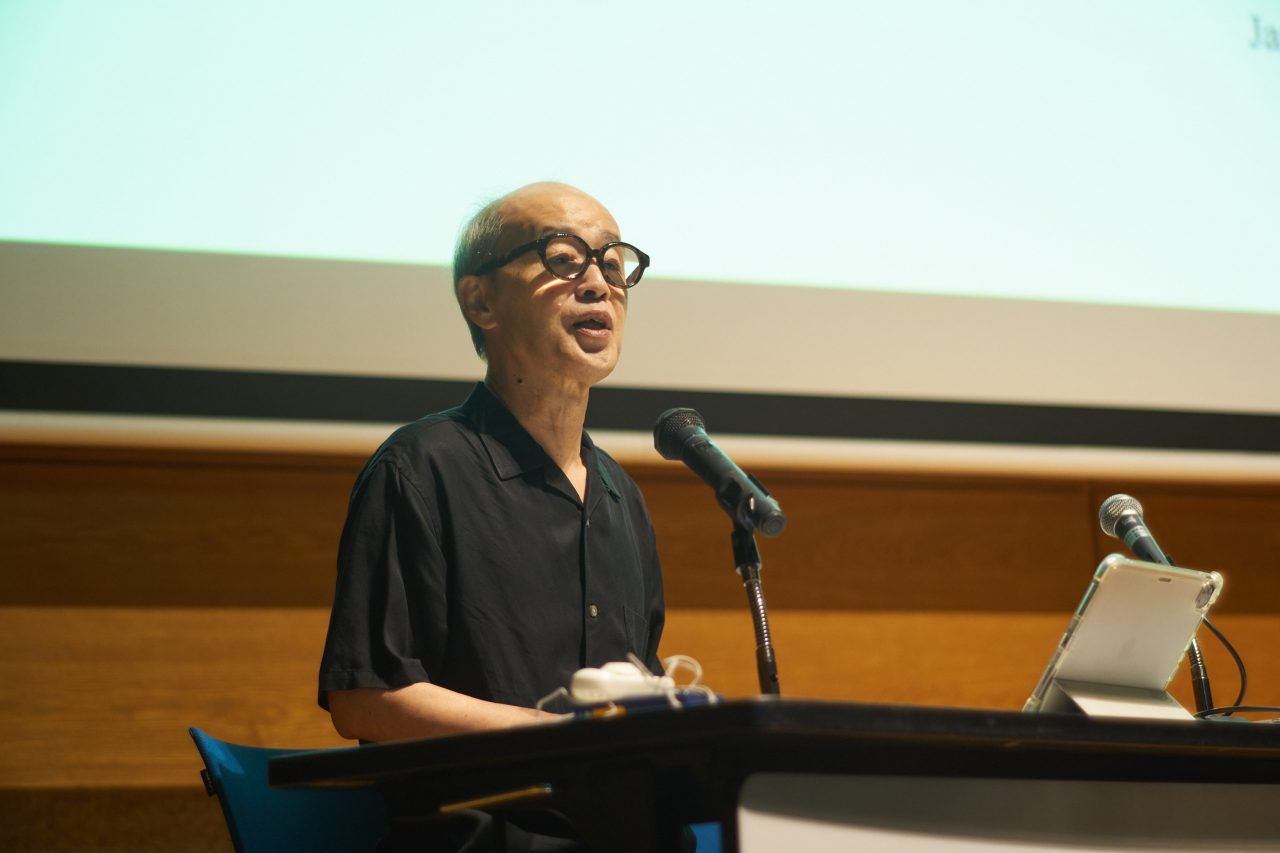

To conclude the symposium, Yoshitake Doi, architectural historian and Professor Emeritus at Kyushu University, summarized the day’s discussions.

Reflecting on the event’s overarching theme of how Shoei Yoh might be positioned in the history of architecture, he noted the significant role exhibitions have played in advancing modern architecture, highlighting the fact that Nikolaus Pevsner’s Pioneers of Modern Design (1936), for instance, was originally a catalogue for an architectural exhibition. He explained that because the history of architectural exhibitions essentially mirrors the history of architecture itself, it should be possible to assess Yoh’s place in history by looking back on how he was represented in exhibitions of Japanese architecture.

-

Yoshitake Doi.

First, Doi focused on the “Japanese” perspective that was formalized by Sutemi Horiguchi in the 1930s. He pointed out that Yoh was absent from Arata Isozaki’s book Japanese-ness in Architecture (2003), as well as from exhibitions such as Japan Architects 1945–2010 (2014) and Japan in Architecture: Genealogies of its Transformation (2018), held at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, and the Mori Art Museum (Tokyo), respectively. Based on these observations, he suggested that the Japanese architectural community does not consider Yoh as emblematic of “Japanese-ness”. Doi also provided an analysis of Yoh’s architecture through keywords such as “postmodern” and “rationalism”. One can read more about his thoughts on Yoh, whose work he witnessed contemporaneously in Kyushu, in the essay he penned for this website, which also ties into the symposium’s presentations.

In his final remarks, Doi proposed that perhaps there is no need to confine Yoh’s work within the framework of “Japanese” architecture at all, but instead it should be considered as a precedent for moving beyond “Japanese” aesthetics. Not regarding Yoh’s architecture as “Japanese” could, in fact, be the highest tribute, aligning with the standard that Yoh himself set by advocating for the development of “non-architecture”. Doi concluded by suggesting that rather than asking “Who is Shoei Yoh?”, the more interesting question to explore is “What does Shoei Yoh inspire in us?”

“Shoei Yoh: A Journey of Light” Symposium Overview

Date: Saturday, September 7, 2024

Time: 14:00–16:50 (doors open at 13:30)

Venue: Architectural Institute of Japan (AIJ) Hall, 5-26-20 Shiba, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan

Language: Japanese and English (simultaneous interpretation available)

Admission: Free

Speakers

Opening remarks: Tomo Inoue (Kyushu University)

Session 1: From Interiors to Non-Architecture

Tracy Huang (University of New South Wales)

Nicole Gardner (University of New South Wales)

Masaaki Iwamoto (Kyushu University)

Moderator : Tomo Inoue (Kyushu University)

Session 2: From Timber to Computation

Koki Akiyoshi (Vuild)

Yu Momoeda (Kyushu University)

K. Daniel Yu (University of New South Wales)

Moderator: Masaaki Iwamoto (Kyushu University)

Closing remarks: Yoshitake Doi (Professor Emeritus at Kyushu University)

Organizer: Window Research Institute

Co-Organizer: Kyushu University Shoei Yoh Archive

Support: Canadian Centre for Architecture, University of New South Wales, Australia-Japan Foundation