Series Windows in Japanese Tea Rooms

Part 3 Shokatei at Katsura Imperial Villa

03 Oct 2018

Members of the Imperial Family were the first to enjoy the luxury of tea, a valuable item at that time, before the art of the tea ceremony was established by Rikyu. They built tearooms called kizoku-gonomi (designed by “kizoku” or the Imperial Family members) often in the soan (rustic house) style and form. These structures give rustic impressions of the soan style at a glance, but closer observation shows that they were designed in refined and elegant ways. Technically speaking, many of them were not designed as “chasitsu” (tearoom) but as “chaya” (teahouse) or more unrestricted structures, and therefore often given names ending with “tei” (gazebo or pavilion without walls).

Shokatei[1] at Katsura Imperial Villa[2]

Part 3 discusses Shokatei at Katsura Imperial Villa. The Katsura Imperial Villa site is dotted with four famous chaya respectively designed to celebrate specific seasons: Gepparo for autumn, Shokin-tei for winter, Shokatei for spring, and Shoiken for summer.

Shokatei, the subject of this essay, is a chaya-type structure situated on a mound made of excavated soil from a pond construction. It is a pavilion consisting of a 2-ken (3.6m) wide and 1.5-ken (2.7m) deep space with an earth floor surrounded by a bench-like raised tatami floor along three sides, forming a C-shape.

The north facade of Shokatei is completely open without any wall. It is covered only with a noren (a kind of curtain with vertical slits hung under the eaves) and offers a panoramic view toward the pond. The remaining three facades have large windows, and this open structure naturally blends into the surrounding greenery.

1.It is said that the Second Prince Hachijo Toshitada relocated Shokatei to the current site from his main residence in Imadegawa.

2.Katsura Imperial Villa was built by the First Prince Hachijo Toshihito (1643-1629), and the Second Prince Toshitada (1619-1662) implemented its renovation and addition.

-

Photographs by Minao Tabata

Light and airy windows in Shokatei

There are three windows in Shokatei: the east and west facades each have a shitaji-mado (window in which the wall substrate is shown) and the south facade has a projected renji-mado (lattice window).

These shitaji-mado are particularly noteworthy because they appear unusually lighter and airier compared with shitaji-mado in other tearooms. The composition of these shitaji-mado cannot be explained based on the theory of tearoom windows I presented in Part 1 and 2.

Firstly, there is no shoji (paper screen) in front of the windows and they are completely open. While one may wonder if these openings are actually “windows”, the composition of the exposed wall substrate in an earthen wall is definitely based on the design theory of shitaji-mado in tearooms.

Secondly, only a very small part of the walls is finished with earth while shitaji-mado take up a large part of the walls. This ratio of the earth-finished area to the entire wall area is contrary to the theory of shitaji-mado because they are supposed to be constructed by leaving some part of the earthen wall unfinished. The west wall especially has almost no earth finish except for a very small area around the window, and the wall substrate is almost entirely exposed. One may think that the wall substrate may not necessary and the wall could be just left open.

Now readers are encouraged to recall my mitate (to see something to resemble another) that the earth wall represents “void”, which I explained in Part 1. These windows and earth walls in Shokatei further clarifies the mitate and hopefully promotes a better understanding of the concept.

-

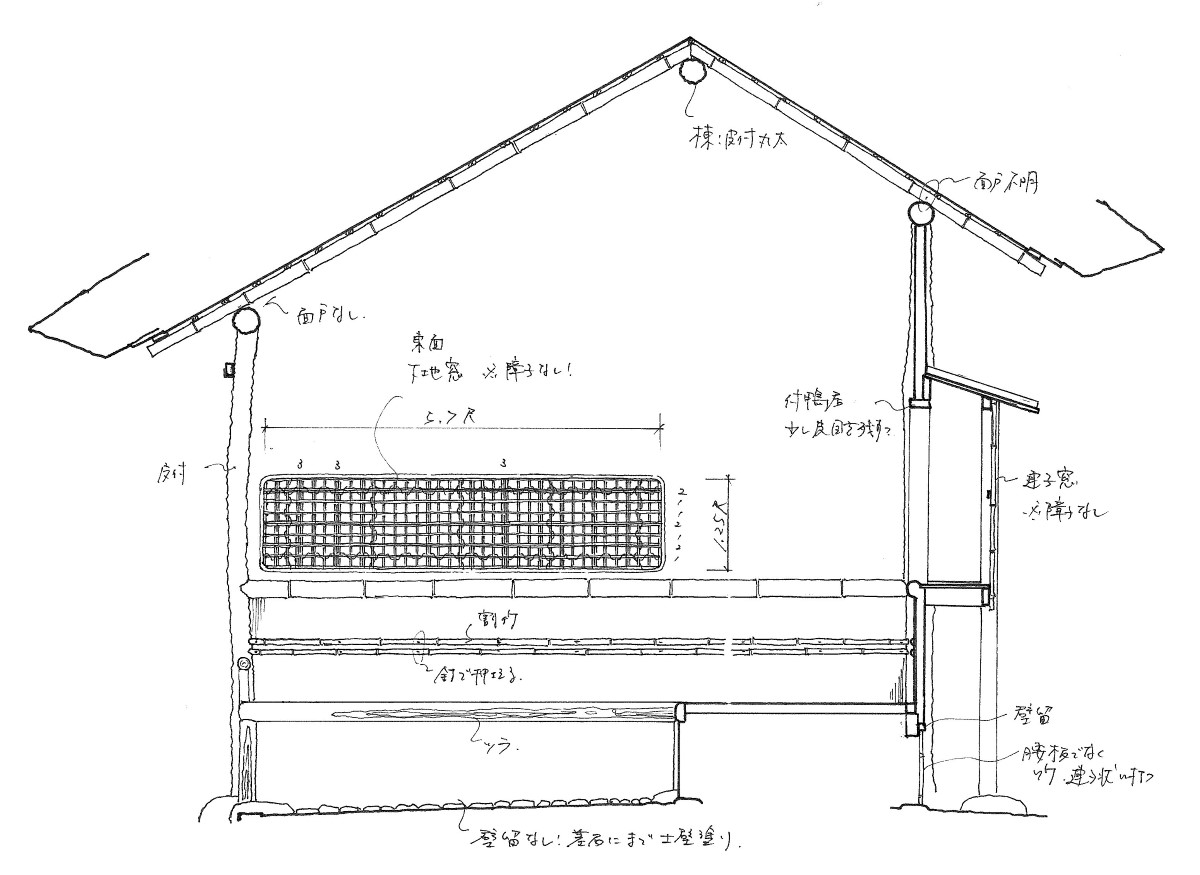

《Shokatei》 East side exterior elevation

-

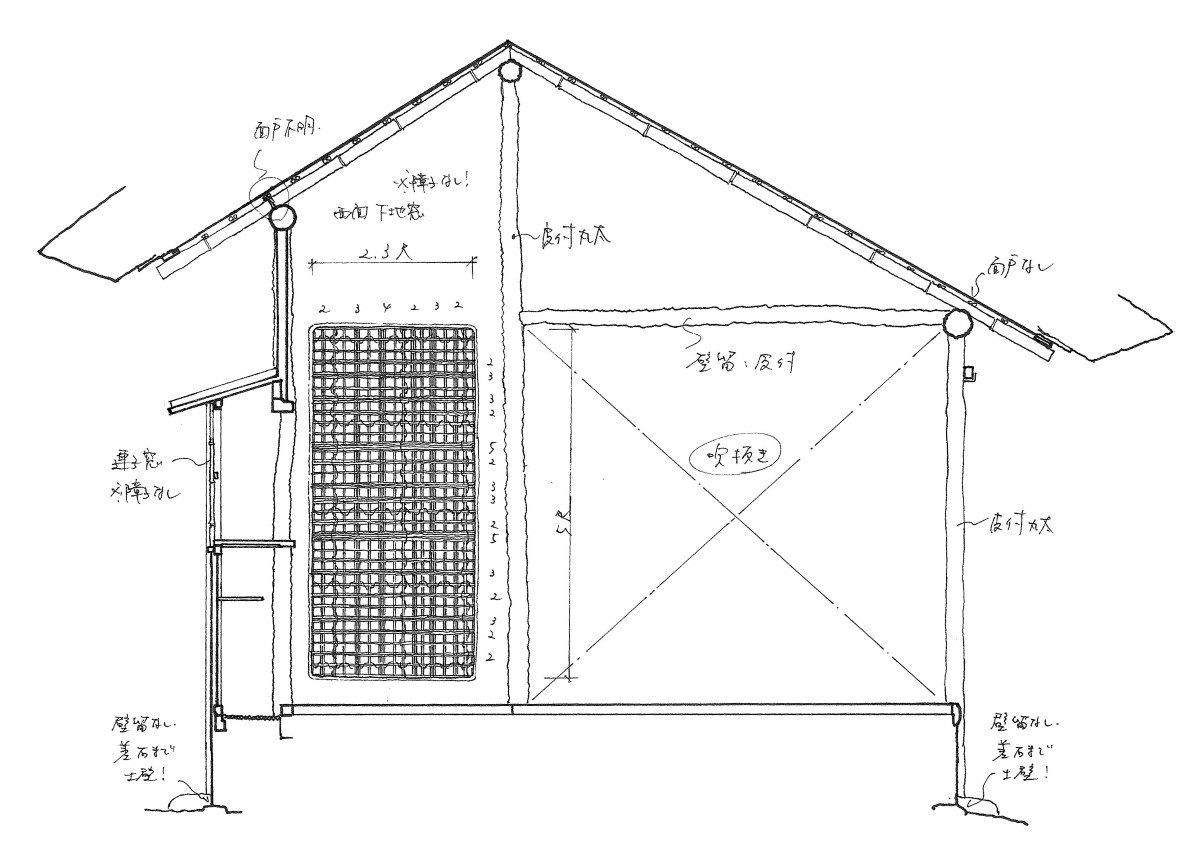

《Shokatei》 West side exterior

-

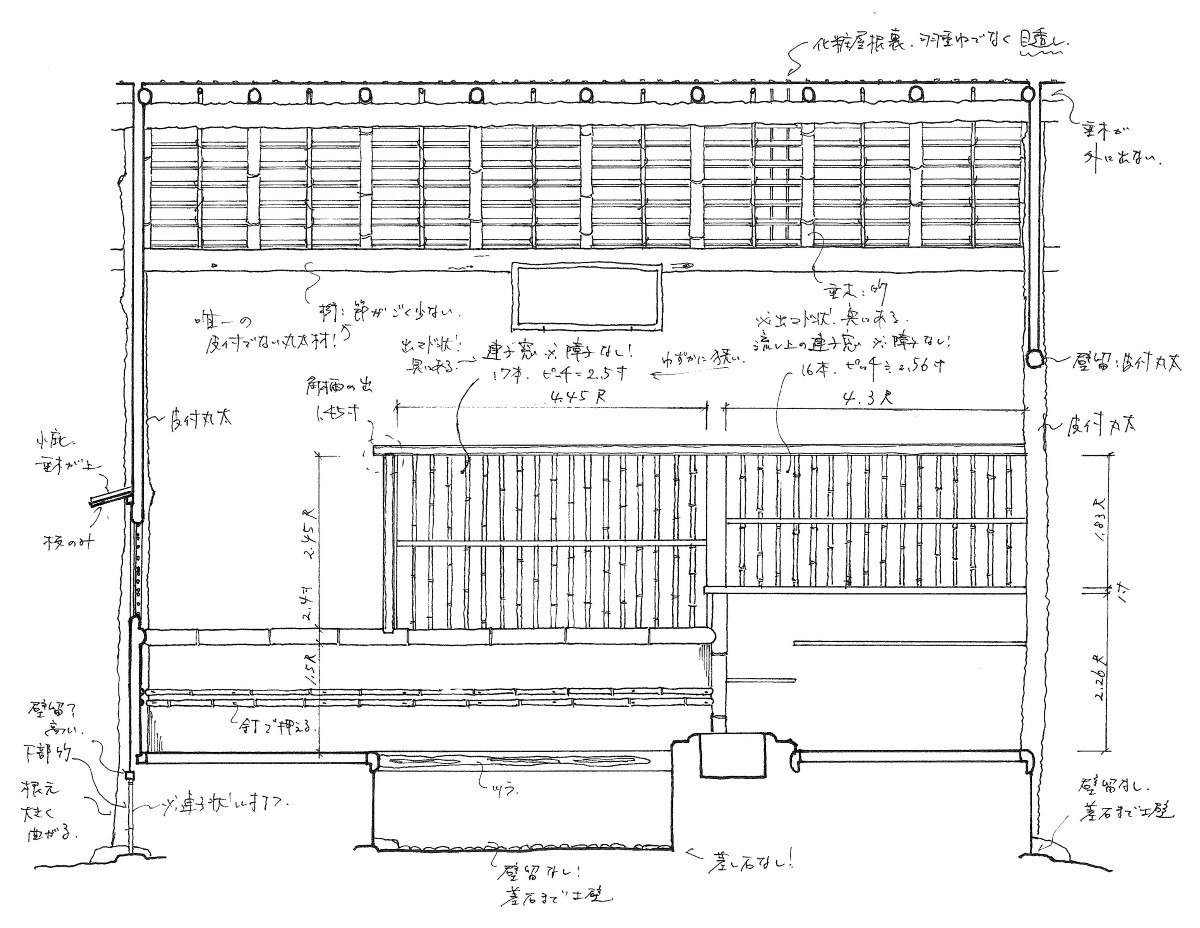

《Shokatei》 South side exterior elevation

Liberation from semiotic conventions of tearoom windows

In addition to the extraordinary visual lightness, the windows give a sense of liberation by detaching themselves from the theory of tearoom windows and create a fresh and delightful atmosphere in “a chaya where people appreciate spring flowers”, which is a meaning of the name “Shokatei”. My interpretation is that this “teahouse for spring” melted heavy snow in winter––or a rigid theory of tearoom windows––in a joyful and relaxed manner that brings a smile to everyone’s face.

Transcending, or playing with the theory

While tearooms were filled with the spirit of innovation and originality in the beginning, they became increasingly rigorous as the methods were eventually established and the theory was formed. In spite of such situations, this chaya in Katsura Imperial Villa and especially the windows transcend and play with the theory to the fullest: the ingenious design including the extraordinary windows, unique layout of tatami and overall composition generate a joyful and lighthearted atmosphere. It is a tearoom full of unfettered ingenuity that only aristocrats and the Imperial family members––or those who had experienced the best of everything–– was able to create.

Other tearooms in Katsura Imperial Villa, including Shoiken with unique renji-mado not discussed in this essay, are also full of unfettered creativity from which we should learn. While those who visit Katsura Imperial Villa probably tend to focus on the wonderful garden and the Shoin-style buildings, I would strongly recommend you to pay attention to the teahouses and the windows on your visit.

Rei Mitsui

Born in 1983, Aichi, Japan, Mitsui conducted Master’s study on Japanese tea rooms at the Graduate School of Engineering, University of Tokyo. After embarking on a career at Shigeru Ban Architects, he established Rei Mitsui Architects in 2015. One of is works, Renovation of “Kanban-Style” building, was featured in a number of prominent Japanese architecture magazines including Shin Kenchiku and Kenchiku Gijutsu. Selected awards include the U-35 / Under 35 Architects exhibition 2017 Gold Medal.