The Smile Sealed Inside a Bubble—Natsume Soseki’s Inside Glass Doors

16 Mar 2021

- Keywords

- Columns

- Essays

- Literature

Natsume Soseki composed Inside Glass Doors at the end of his life. From inside his room, the “I” of these essays watches the days go by, meditating over visions of the past. Toshiyuki Horie, writer and scholar of French literature, unpacks the curious nature of these literary sketches. Among the major figures of Japanese literature, Horie is best known outside Japan for The Bear and the Paving Stone, which has been translated into English. An admirer of Soseki and the author of the book of essays Wandering Windows, Horie offers an alluring treatment of how “Soseki and windows” intersect.

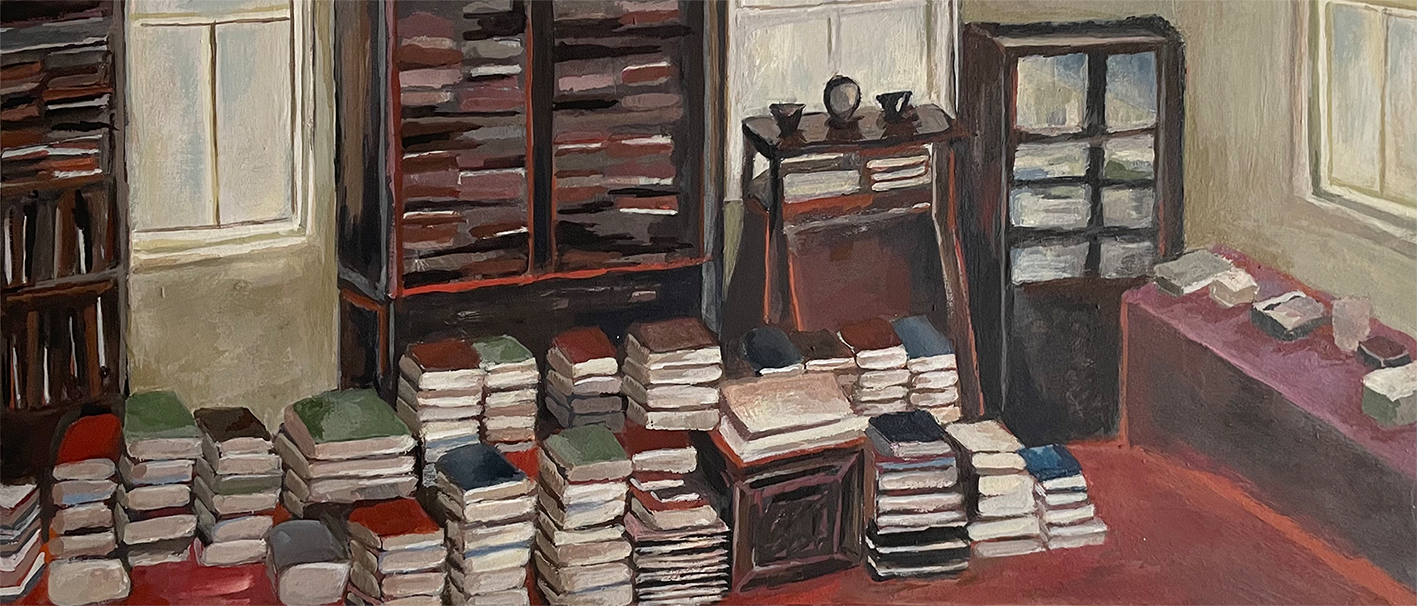

In middle school or maybe high school, I had my first encounter with a photograph of Natsume Soseki’s study, printed in a handbook that accompanied my textbook for language class. It was a picture of his writing quarters in the Tokyo neighborhood of Waseda Minamicho. On account of being black and white, the true colors are a mystery, but a small, low writing desk is visible in the foreground, laden with manuscript paper, brushes, and dictionaries, behind which he sits on a plaid zabuton, with a giant brazier to his right, holding a substantial teapot that looks to have been cast. Foremost, I was fascinated by the tidy mountain range of books piled behind him. The books he was using, may use soon, or was hoping to reread formed a modest colonnade of knowledge, with no end in sight, and linking with the books stacked in the bookshelves to the rear along the wall, suggestive of a beautiful work routine. A clean desk with plenty of light, the ideal work environment.

Soseki moved into the house that had this study in September 1907, about six months after he had joined the staff of the Asahi Shimbun in the peculiar capacity of salaried fiction writer, and soon after completing The Poppy, his first novel for the paper. This is the study where Soseki wrote book after book, while suffering chronic stomach pains, until his death in 1916 at the age of 49, midway through the serialization of Light and Darkness. He used the neighboring living room to host guests at literary salons every week, granting these two rooms the status of undisputed holy sites among his readers, but given that the living room was a washitsu, floored with tatami mats, I had always assumed, from the low desk and the brazier, not to mention the author dressed in a kimono, that the study was tatami, too.

However, when I read a conversation titled “Lifestyle of the Author” (March 22, 1914, Asahi Shimbun, Osaka Edition) in a supplementary volume to a pocket size edition of his complete works I bought for cheap in college, I realized my assumption had been foolish. In actuality, the room was Western style, meaning wooden floors. “This house may have seven different rooms, but I use two of them myself, and the six kids easily use up the rest. The rent is 35 yen.” First occupied by a physician, the rambling mansion is encircled by a veranda with a handrail, which, when viewed through the Western-style sash window to the left of his desk, makes for a colonial atmosphere vaguely reminiscent of the South Sea Islands. Though hard to make out from the photograph, in which the shades are drawn, there are two slender windows in the wall behind the desk as well, dispelling my idealistic image of a workspace filled with sunlight.

“I like a brighter house. I’d like to move into a cleaner space. The walls of my study are crumbling down. Water stains up in the leaky ceiling, dirty all around, but since no one bothers looking at the ceiling, I’ll live with this for now. As you can see, the floor is wooden, no tatami. The wind blows through the boards, which in the winter is insufferable. And the light is bad. It’s a pain to sit like this and read and write, but if I start worrying about that, it never stops, so I’ve decided not to let it bother me. One time someone came by and suggested that I paper over the ceiling, but I refuse to do so. It’s not like I’m living in this dark and dirty house because I like it here. I’m only here as long as necessary.”

At the home in Negishi where his friend Masaoka Shiki lay ill in bed, glass doors, which at the time were still a rarity, allowed the poet to view the garden from a reclined position. The doors were given to Shiki by Kyoshi Takahama in December 1899. In short time, Shiki wrote to Soseki to say the windows on the south wall of his sickroom had been replaced with these “shoji made of glass,” which blocked the cold air but allowed the warming daylight to come through. Perhaps a photograph of Shiki’s chamber, imprinted on my memory, was in part responsible for my false image of Soseki’s study being all tatami, a bright space surrounded by old-fashioned glass, replete with air bubbles, and smelling of soft rush. I never had suspected that it had the Western-style sash windows he probably had back in his boarding house in London, when he lived abroad.

“Looking out from my glass doors, my eyes meet with banana trees, tented against the frost, holly branches bearing their red berries, and telephone poles standing shamelessly upright, but almost nothing else worth noting enters into my vision. The world seen from my study is exceedingly plain, as well as exceedingly small.”

Thus begins Inside Glass Doors, serialized in the Asahi Shimbun in 1915 over thirty-nine installments, from January 13 to February 23. The narrator has been confined to the purview of this glass room, stricken with a cold since the end of the last year, and says that he “knows nothing of the state of the world, feeling so bad that I rarely even read or write.” To be sure, Soseki had not been in good health. Just after finishing the novel Kokoro the previous summer, he had suffered his fourth gastric ulcer in September and was in poor condition through the end of October. All the same, because he was a professional writer, collecting a salary from the newspaper, he pushed himself to compose this collection of short sketches. Jumping ahead to March of the next year, he was hit with his fifth ulcer, only to serialize Grass on the Wayside from June to September. His body was steadily deteriorating. At this point, he had only a little over one year left to live.

As if sensing this, the narrator of Inside Glass Doors glazes his very heart, deriving strength from the dead, that he may delve deep into memory and reveal himself to others, as with an X-ray photograph showing the contents of the chest, though taken in a room so poorly lit they have to burn magnesium to see. In fact, he voluntarily trades places with the dead, in order to look into this world from the other side. His desire being not to hide the blemishes in the ceiling, but to fix his gaze upon them.

The “I” of the essay is cowering inside of a transparent glass enclosure. Almost like a cat, or like the puppy he is given. The anecdote delivered in one stretch from chapters three to five of the beloved canine Hector, who shows up swaddled in a cloth, is none other than the mark of life left on the narrator, finally emerging from the surface. On Hector’s first evening at the house, the narrator makes a place for him to sleep inside a shed out back, a fresh bed of straw just for him. But as night falls, the puppy begins howling, clawing at the door to get out. “As if mortified of sleeping alone in the dark, he would not let up the entire night.” Because this was a simple door of wood, he could not see inside. From this side of the glass doors, the narrator attunes himself to the darkness beyond and the isolation of the puppy.

Soseki was a late arrival to his family, separated by a number of years from his siblings. Disgraced by this unexpected pregnancy, his mother put him up for adoption soon after giving birth. There are two different stories, either he was entrusted with the family of a secondhand store in Yotsuya, which the older sister of the Soseki household’s maidservant had married into, or with a grocer in Genbemura (today, Nishi Waseda), but in either case, he would have been set down in a pot or basket while his foster parents tended to their business. As it turns out, “I” offers corroboration for the former in chapter twenty-nine.

“Every evening, I was placed into a little basket in the middle of the madness of that secondhand store, exposed to the night traffic of Yotsuya. One evening, my sister happened by and saw me there. She must have taken pity on me, since she slipped me into her kimono and brought me home, but that night I cried so hard I was unable to sleep, which won my sister an awful chiding from our father.”

The “I” inside the glass doors sees himself, at an age too young for him to recall, in the same light as the puppy he is later given. Just as Hector is unable to let up for the entire night, the narrator is unable to sleep. Kinnosuke, as Soseki was known at birth, was adopted, taken back, then adopted again, only to be picked up, basket and all, by his original family at the age of nine, due to problems with the new adopted family, but he was not reenrolled in the family registry until 1888, at age twenty-one. The loneliness and isolation rising from the depths of his awareness is reflected in the way he meets and loses Hector. One day, the dog disappears. About a week later, it is found floating in a pond beside another house “a couple hundred yards away.” Their maidservant comes by to let him know. Refusing her offer to bury it for them, the narrator calls a rickshaw, which returns the dog to him wrapped in a straw mat. They bury the dog in the garden, marking his grave with a length of plain wood, on which the narrator inscribes this haiku: “Rest now below the earth, where you will not hear the autumn wind.” There was already a cat buried elsewhere in the garden.

“When I step onto the north veranda of my study, poorly lit by the cold sun, and peer into the backyard ravaged by the frost, I can make out both spots clearly.”

The two graves hint at the death that will greet him before long. Perhaps this sentiment could only have been born from deep consideration of the world outside, as seen from within the glass doors. Blending the trifles of daily life with the gravity of memory, the narrator reexamines his existence. Mirrors are not the only means of reflection. Photographs can lend a hand as well.

A visit from the editor of a certain magazine who comes to take a photograph is recounted in chapter two. When the man first calls up and proposes to come by for a photo shoot, the narrator asks, “Am I correct you only publish photographs of people smiling?” When the editor denies this, the narrator concedes, on the condition that he is permitted to make a “normal face.” On the day of the shoot, however, he is asked to smile after all. He ignores this request, but when the photographs arrive later on, there is a definite smile on his face. This comes as a surprise. Deciding that a smile has been doctored into the photo, he asks his family members to confirm, and they agree. As humorous as this anecdote may be, there is a movement in the eyes of this second version of himself, smiling sadly as he looks back at himself and sees a man unwilling to smile. The reader is struck by the loneliness of this self-scrutiny, which can only process the innocent idea of smiling at another person in the same terms as the stains on his ceiling.

Seated from page one, the narrator stands up in the final chapter, opens the glass doors, and looks out into the garden. Not simply gazing off into his soul, he offers a surprising declaration. “I smile as I look upon the whole of humanity.” The smile he refused to show another person, on request, he now directs upon “the whole of humanity.”

“And I look upon myself, the person who composed all these trivialities, as if he were a different person, and can’t help but continue smiling.”

Winter turns to spring overnight. The grumpy face is overtaken by an unfabricated smile. And yet this sense of peace is all too fleeting. Both Hector and the narrator cry out, from their sadness and isolation. Knowing the scars in their experience of life can never go away.

“Are we not all, without exception, carrying a bomb we made ourselves in a dream, living out a fantasy as we journey to the faraway land called death and chat along the way?”

As alluded to in chapter thirty, Inside Glass Doors was composed “in the midst” of the First World War, in which the Empire of Japan took part. The grandiloquent statement about the whole of humanity, from which his study was significantly removed, finally takes on meaning through the narrator’s stern depiction of the damage to the roof and ceiling, which could leak in earnest any minute, and the locus of the bomb inside his heart, which could explode any second. Sealed within the glass bubble encompassing this book of essays is a smile of the sort only permitted to those conscious of the close proximity of their own death. Infinitely close to the narrator, Soseki plumbed the boundaries of the bubble, but died without taking it down.

Toshiyuki Horie

Toshiyuki Horie is a writer and a scholar of French literature. After graduating from Waseda University with a degree in French Studies, he began a Ph.D. at Tokyo University. On a scholarship from the French government, he studied abroad at Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3. In 1995, he made his debut with To the Suburbs (Hakusuisha), an essayistic account of his experience studying in France. In 2001, his novel The Bear and the Paving Stone (Kodansha) was awarded the 124th Akutagawa Prize. Today, he teaches in the Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences at Waseda University. His major works include How the Shape Disappears (Shinchosha), The Space They Filled (Nikkei), On Cloudy Skies (Toshi Shuppan), and Under the Old Lens God (Bungeishunjusha).