Rei Naito: Mirror Creation

02 Nov 2020

- Keywords

- Art

- Interviews

Rei Naito is an artist who creates works that converse with the environments that surround them, posing the question “Isn’t simply existing on the earth a blessing in itself?” In the case of Mirror Creation, her solo exhibition at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, her works are illuminated by natural light streaming in through the glass walls and skylights in a space designed by SANAA. The window and the other works displayed in this exhibition employ openings and reflections to create intersections between seeing and being seen. Here we discuss with the artist the role of windows in her work.

The unusual architecture of the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art employs both external and internal transparent glass walls. Your exhibition uses the museum’s corridors and light courts as well as its galleries. How did you envision that space when thinking about this exhibition?

In a way impossible with other museums, this museum allows the incorporation of a wide variety of scenery and transient events. We can see people strolling through the corridors and those outside on the city street. Changes in natural light and the sky are visible everywhere. If we imagine the museum as a place to turn inward, this museum is totally the opposite. Over there we see a tree. We can also see people at work, and moments when clouds cover the sky. For better or worse, displaying these works at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art meant having to accept all the possibilities constructed by this architecture.

-

fig. 1. Rei Naito, the spirit, 2020

I want all of my works to be understood as connected with and evoke the nature of the architecture and all of the moments it reveals. That wealth of transformations brings instability. However, I don’t want to end up not seeing all the moments that appear, even those not one does not intend to see, including that element of instability. In other words, in these works and their arrangement I wanted to “mirror” everything, even things that might appear to bear no relationship to them. I was trying perhaps to capture “the scene of life upon earth.”

What is this “mirroring” you speak of?

The Japanese term utsusu, translated here as “mirroring,” is expressed in Chinese characters with a variety of meanings—to shift or replace, to copy, to project, to transmit—but in all cases the big, underlying meaning is the same. The concept life and death was the foundation on which I constructed and arranged all of these works. I came to believe that things which seem to be polar opposites might be fundamentally the same. I wanted to show that the more things are seen as antithetical, the more they return to the same origin. To me that is what “mirroring” means. In this exhibition, that relationship occurs on many levels, humanity and nature, me and you, light and darkness, art and observer, art and artist.

-

fig. 2. Rei Naito, matrix, 2020, untitled, 2020, human, 2011-2020

In this exhibition, the works are shown, in the daytime, in an environment where they are illuminated only by natural light from the glass walls and roof. Your earlier works also incorporated natural light. Was there some particular trigger for this?

My inspiration was Being Given (Kinza, Art House Project, Naoshima, Kagawa, 2001). I was asked by the Art House Project to create a work that would combine a small, empty traditional house and its garden. But when I went to see the house, it still contained many household furnishings. I felt so strongly the lives of the persons who had lived there that it didn’t feel right for me to touch them. Because, however, the house retained the form in which several generations had lived there, I thought that I could do something with the house itself. So I removed everything, including the floor and ceiling, except for the bare minimum to retain the original structure. All that remained was the roof, walls, and six pillars. The earth, so long blocked from view, was revealed. While “houses are built on top of the earth” is perfectly obvious, there was something surprising, something discovered.

At that moment, I noticed that a portion of the wall had broken off, allowing light to leak in from below. There were rainy days while I was staying there. The water that leaked through that crack glittered in the light. Seeing that water leaking had a strong impact, strengthening awareness of the reality outside. The distinction between uchi and soto, inside and outside, was sharply drawn. That was, in this sense, a small window.

What you call an “opening”?

Yes, so I decided to make an earthen floor by pounding it and have openings created only at the base of the building through which light could enter from below, on all sides of the house. That meant that not only light, but also voices and other signs of what was happening could enter, too. When that happened, I felt an affectionate attachment to those living people. We might not know their names and whether they were neighbors or tourists. All we could see would be their steps as they walked by.

-

fig. 3. Rei Naito, Being given, 2001, Art House Project "Kinza", Naoshima, Kagawa, Benesse Art Site Naoshima

Photo: Naoya Hatakeyama

Since the visitors who come to see this work are only allowed to go in one at a time, when I was inside, it seemed, in a sense, that all the other people on the earth are on the outside. (Laughing.) I was alone but would feel the presence of every other human everywhere on Earth. Something like the touch of all those others walked on the same earth intensified. At that moment, a feeling I had never felt before began to grow inside me. That was the inspiration.

In an earlier work, I had placed a lamp in the middle of a tent. Whenever someone entered it was always the same. I thought that the point of the work was to maintain that state, but instead I received the changes that occurred over the course of the day. Due to the earth and the light.

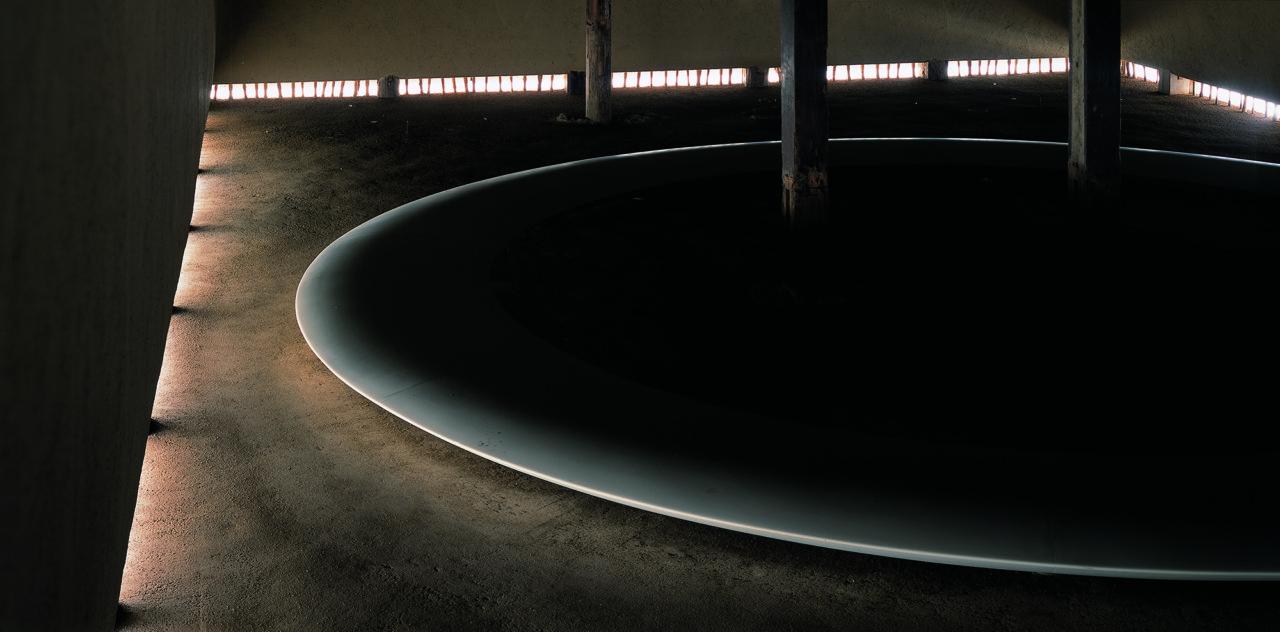

The Teshima Art Museum can, it seems to me, be seen as another example of a work in which, in that case, a huge opening through which nature and architecture interconnect. That work was a collaboration with the architect Nishizawa Ryue. Could this work be considered an extension of the experience that led to Being Given?

Yes. It was while working on Being Given that I became aware of place and began to think about how including the light, the sounds, the smells, the people, even the darkness, whatever was and whatever happened there would enrich a work. The biggest issue for me in creating Matrix for the Teshima Art Museum was receptivity, how the work would embrace the world around it.

-

fig. 4. Rei Naito, Matrix, 2010, Teshima Art Museum, Kagawa [Architect: Ryue Nishizawa], Benesse Art Site Naoshima

Photo: Ken’ichi Suzuki

That said, in your book Sora wo mite yokatta [It was good to see the sky](Shinchosha, 2020), you write that, looking from your veranda at an apartment lit only by the light coming through your own place’s window, “I felt a heartrending pain, as though I had somehow glimpsed one person’s small but entire human life.” This can also be seen in the catalog of your exhibition Rei Naito: on this Bright Earth I see you at Contemporary Art Center, Art Tower Mito (2019): “Wasn’t it an experience of compassion, of looking from ‘the outside of life’ into ‘the inside of life’.” Can we talk about that experience?

In those moments I felt, “I see myself.” I was usually working in another room. By chance, the sunset was gorgeous and I stepped out on the veranda. I noticed how the alley was barely wide enough for people to walk down. For the first time I saw my apartment from outside. Windows are often called screens, and that was the effect. Outside the light was fading. There was no one in the room. But the lights were turned on, allowing me to see everything clearly.

Scenes and feelings, my whole life, flashed across my memory like images on a revolving lantern. Later, talking with a friend, I learned that contemplating your room from outside through a window is a discipline imposed on monks in training.

-

fig. 5. Rei Naito, matrix, 2020, human, 2020, human, 2020

Hearing that, I was persuaded. I felt that I had experienced that training, contemplating my life from the outside. It may have been something close to that feeling. At that time, there were no buildings similar in height to my home surrounding where I was living. In that sense, I was seeing a landscape that no one had seen before. Seeing my own room as that kind of landscape may have been a big factor.

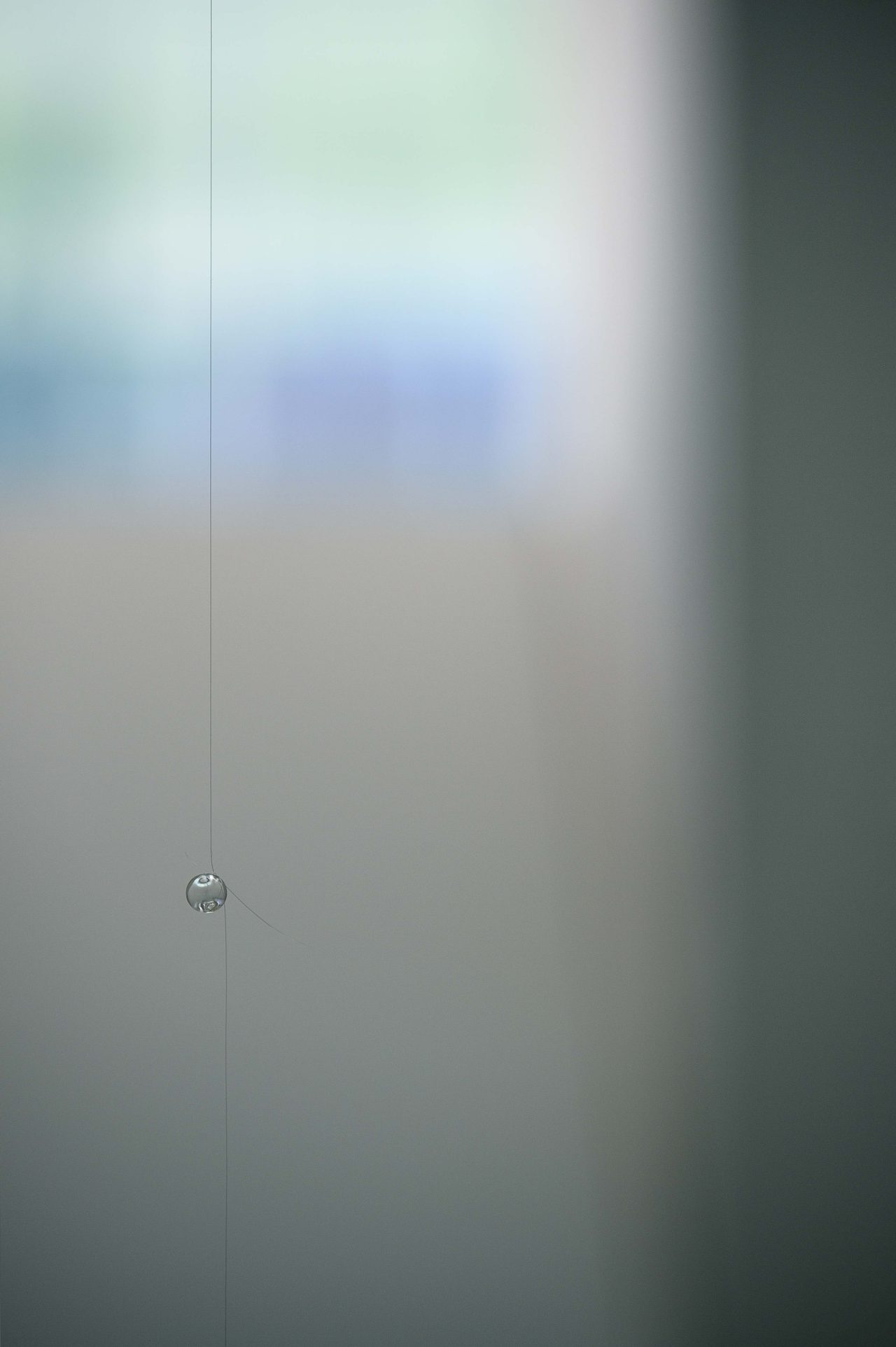

At this exhibition you are showing a work titled window (fig. 7). An oblong pane of glass is attached to a wall, in a gallery where little natural light enters even at midday. Is this work related to the experience you just described?

Yes. The first work in which I tried to give form to that experience on the veranda was shown at the Naito Rei: Tout animal est dans le monde comme de l’eau a l’interieur de l’eau exhibition in Kamakura in 2009 (fig. 6). That was around five years afterwards.

For that work in Kamakura, to view it, people had to remove their shoes and pass through what appeared to be the kind of glass case in which museums present exhibits. The interior of the case represented “inside of life,” the gallery around it “outside of life.” The presence in the gallery space of “outside of life” — the dead, the unborn, animals, spirits, that is, everything apart from living human beings—focused attention on the living presence of those inside the glass case.

Inside the glass case I used cloth and ribbons to create a small, cute landscape, to which I added an offering of water. The balloons in front of the glass case are a decoration intended to comfort, encourage, approve, and celebrate people’s “inside of life.”

-

fig. 6. Rei Naito, What Kind of Place was the Earth?, 2009,

Installation view: Naito Rei: Tout animal est dans le monde comme de l’eau à l’intérieur de l’eau, The Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura, 2009

Thus, while living people may comfort the souls of the dead, the intention here is the reverse, to focus on the living through the eyes of the dead. That was, it seems to me, the feeling I had looking into my room from the veranda. I have just mentioned showing love and compassion toward the living; a similar feeling was born directed toward myself.

The window in this exhibition is connected with the work I exhibited in Kamakura. Because people already in the space will see others who entering from the entrance at the rear reflected in the glass, it will seem to them that “The living have just appeared among us.” The crumpled gravure prints featuring an image of a laughing woman and the small pieces of cloth with botanical motifs, which touch the window frame, are decorations that express and affirm the presence of life (fig. 8).

-

fig. 7. Rei Naito, What Kind of Place was the Earth?, 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, 2020

-

fig. 8. (from left) Rei Naito, Grace, 2020, Face (the joys were greater), 2020, color beginning, 2020

As visitors enter the exhibition space, they see, for the first time, your work human (fig. 5) in the gallery through the windows in the museum building. Then, in the last gallery, they see untitled, a work in the form of a window, creating a structure at the place that was originally an entrance or exit through which they can enter or leave (fig. 9).

Because there is a boundary, visitors have the experience seeing but not being able to go, a place they should not enter or occupy. While standing beside the work, they feel it is an event happening far away. Because human is so small, it creates an extra sense of distance.

In contrast, through the opening in the last gallery, they see people at the entrance, just beginning their visit, in other words society, life, everyday things. At the last moment they see people. Actually, as in window, those viewing it see and are seen by each other. But those who see others beyond the opening do not notice that they are seen in return. That experience is a bit uncanny. But that is why seeing others you don’t know through a window arouses such strong feelings.

At the end they see things that are not your works of art.

Those are not works of art. The last scene in this exhibition is the real world. I have never imagined arriving at such a reality at the end of a work’s composition. Instead, for the first time, I am imagining that I myself have arrived. I do wonder though, having said so much, what comes next. (Laughing.)

-

fig. 9. Rei Naito, matrix, 2020

For this exhibition the museum is also open at night. Standing in pitch black darkness, everyone shares one window. When we saw the light pouring in, we somehow feel encouraged.

At night that window is the only source of light. Because the light and the works lack the colors they have during the day, everything is monotone. The only color is in the landscape seen through the window. The world beyond the window is colorful indeed.

As I was creating the works for this exhibition, I discovered something new about color. In April, when the decision to extend the exhibition was made, I painted a picture of the window room (fig. 8). I was asking myself why I was so surprised and happy when color appeared. My discovering color led to my producing that painting. This world is filled to overflowing with color. Color, light, and life appear simultaneously. That they are inseparable is something I tried to convey in this work.

-

fig. 10. Rei Naito, matrix, 2020

During your talk, you said, “I try to think that what is in front of my eyes is good.” Why is it that you see and affirm life through all of your work?

Better, perhaps, than saying “affirmation” would be to say “acceptance.” Death is inescapable. But to have received all this, my life included, without doing anything to deserve it continues to amaze me. Nature, in particular, affects me this way. That humanity was born, that I am alive, that life goes on: none of these are the result of human intentions. I want to notice the joy given to people, amid the decisive, yet so hard fully to accept, circumstance, as long as I am alive. That is what keeps me going.

Rei Naito

Born in Hiroshima in 1961; currently lives in Tokyo. Graduated from the Visual Communication Design Department at Musashino Art University. After receiving acclaim for une place sur la Terre, shown at the Sagacho Exhibit Space in 1991, Naito went on to show the work in the Japan Pavilion at the 47th Venice Biennale. Her major solo exhibitions include Migoto ni harete otozureru wo mate (The National Museum of Art, Osaka, 1995); Being Called (Galerie im Karmeliterkloster, Frankfurt am Main, 1997); Tout animal est dans le monde comme de l’eau à l’intérieur de l’eau (The Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura, Kanagawa, 2009); the emotion of belief (Tokyo Metropolitan Teien Art Museum, 2014); émotions de croire (Maison de la culture du Japon à Paris, 2017); Two Lives (Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 2017), on this bright Earth I see you (Contemporary Art Gallery, Art Tower Mito, 2018); and Mirror Creation (21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, 2020).

Her permanent works include Being given (Kinza, Art House Project, Benesse Art Site Naoshima, 2001) and Matrix (Teshima Art Museum, 2010).

Exhibition: Rei Naito: Mirror Creation

Venue: 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa

Dates: Saturday, June 27 – Sunday, August 23, 2020

https://www.kanazawa21.jp/en/

Top Image

Rei Naito, matrix, 2020

Installation view: Rei Naito: Mirror Creation, 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, 2020

Photo: Naoya Hatakeyama

fig. 1−2, 5, 7-10

Installation view: Rei Naito: Mirror Creation, 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, 2020

Photo: Naoya Hatakeyama