Windows in Photography:

Conversations with Iwan Baan, Takashi Homma and Yoshiharu Tsukamoto

09 Apr 2020

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Conversations

- Featured Architecture

- Interviews

- Photography

- Windowology 10th Anniversary Exhibition & Symposium

Three panelists discuss how photography, architecture, and windows are interrelated. They are Iwan Baan, who has been photographing prominent architectural works by the world’s leading architects including Rem Koolhaas and Toyo Ito; photographer Takashi Homma, who has been conducting research on windows and photography and presenting his views through his photographic work on Le Corbusier; and architect Yoshiharu Tsukamoto (Atelier Bow-Wow / Professor, TIT), who has been exploring the relationship between windows and human behavior.

Moderator: Taro Igarashi (Professor, Tohoku University / Architectural Historian and Critic)

* This article has been adapted from a lecture given at the Windowology Symposium, held in Tokyo, 2017.

Taro Igarashi: Firstly, the two photographers will respectively present their architecture photos with a focus on windows. Please welcome Mr. Iwan Baan.

Photographing People’s Lives along with Architecture in the World

Iwan Baan: I would like to give a quick introduction to a couple of my recent projects where windows played an important role.

This is a new museum for contemporary art – Zeitz MOCAA – designed by Thomas Heatherwick in South Africa — the very first museum, actually, of contemporary art on the African continent [pict_01]. It uses these big bulging windows, which kind of reflect the whole city. These windows create all kinds of different reflections of the whole city on the glass outside.

-

[pict_01] Photo: Iwan Baan

I have collaborated with many different architects such as Herzog & de Meuron, Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas, Steven Holl, Toyo Ito, and Wang Shu, all of whom use lights and windows in very specific ways. I’m very fortunate to have been able to work with many of the great architects of our time.

However, I don’t really consider myself an architectural photographer. Of course, a lot of my commissioned work tends to come directly from architects, but it’s incredible how so many buildings that are basically similar to each other end up being created all around the world. This is something I try to avoid, and I’m always trying to find examples of how architects use design, light, and space in a very particular way.

-

Iwan Baan

These are some pictures from a book – African Modernism: The Architecture of Independence: Ghana, Senegal, Côte D’ivoire, Kenya, Zambia (Park Book) – on African modernism that I produced in 2015, where we looked at five countries all over Africa.

This is Nairobi [pict_02], where architects in the 1960s-70s did some incredible, modernist work that has been largely forgotten. You can also see here the specific ways in which direct sunlight in Africa creates certain climatic conditions. Windows are used not only to bring light inside. Often, shading systems in front of the windows are also deployed to filter the light again and create a cooler climate inside. Often, the windows kind of disappear over time. Or they could end up being used in different ways: the shading system is sometimes used to store shoes or all kinds of other materials in front of the windows. It creates these different layers in the buildings.

-

[pict_02] Photo: Iwan Baan

This is a beautiful exhibition center in Senegal [pict_03]. There are these triangular buildings where the windows also frame another triangular view inside. Elsewhere, the windows, or the area in front of the windows, build another shading system, while also becoming balconies and serving as other lookout points. When you build an art school in a climate like this, where the windows are completely open, but where the people also make use of the outside space because the climate allows it, the windows are really just a kind of frame that can be deployed for other purposes.

-

[pict_03] Photo: Iwan Baan

This was a project “Torre David / Gran Horizonte” that I presented at the Venice Biennale a couple years ago — shot in Caracas, Venezuela of this incredible tower, an abandoned office tower that was never finished [pict_04]. The tower had 45 stories that people started to take over. Over a couple of years, almost 3,000 people took over this building and built an entire vertical city in that building completely by themselves. They also made their own windows, sometimes by knocking through the walls and creating spaces in between. They used the lights, and the filtering of the lights in a way that was designed — not by architects, but by the people themselves.

-

[pict_04] Photo: Iwan Baan

This is a refugee camp in the south of Algeria where people moved 40 years ago, after the war [pict_05]. They were taken in by the UNHCR, which built a whole temporary refugee camp there. 40 years later, however, these people are still there. Without any resources or any form of access, they started to build this whole city that today houses some 160,000 people. It is also very hot in the south, in the Sahara. Small windows are often very carefully designed. For the entrance doors here, the arch is also made out of a tire to support the window. All these kinds of details are used in very specific ways, in order to try and mimic windows, in a sense, without recourse to architects and planners.

-

[pict_05] Photo: Iwan Baan

Even when you step into the photo studios, they seemed to have become something of a real city over time [pict_06]. You have photo studios, shops, and everything in a temporary refugee camp. Inside the photo studio, people want to have a background of a real city. You’re in the middle of the Sahara, where there’s basically nothing. As a background for your picture, however, which you have taken there, people put up a background of windows looking out onto the landscape — a landscape that they’ve probably never seen themselves, but which frames a completely new view.

-

[pict_06] Photo: Iwan Baan

Yoshiharu Tsukamoto: Your photos encompass an extremely wide range of architecture. There are two extremes, namely starchitects’ buildings for one and abandoned buildings in obscure corners of the world for the other, as well as many buildings in between. Before the period of high economic growth, only selected architects needed to make architecture within the established world. But due to occurrences of conflicts, recessions, and natural disasters, architecture are diversified in terms of materials and contexts and architects can no longer categorized into certain groups as a result. Iwan’s photos seem to capture such existing situations in architecture today. I was particularly moved by the photos of people making buildings and installing windows at the refugee camp.

Igarashi: I felt as if I just got back from a super-fast trip around the world, across Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America with so many images. Iwan’s photos capture diverse objects ranging from contemporary architecture to self-built spaces in refugee camps––and also people in these places.

Going Back to the Principle of Photography

Takashi Homma: I had been photographing various types of architecture before I started the Windowlogy research. I am particularly interested in windows. In addition to photographing windows as such, I am interested in the scenery seen through the window as well as the line of vision.

For example, in the series entitled “Architectural Landscapes” (Gallery White Room Tokyo, 2007), I photographed the works of Oscar Niemeyer and Case Study Houses designed by architects, showing the contrast between the exterior appearance of architecture and the view of the surrounding scenery from the site [pict_07].

-

[pict_07] Photo: Takashi Homma

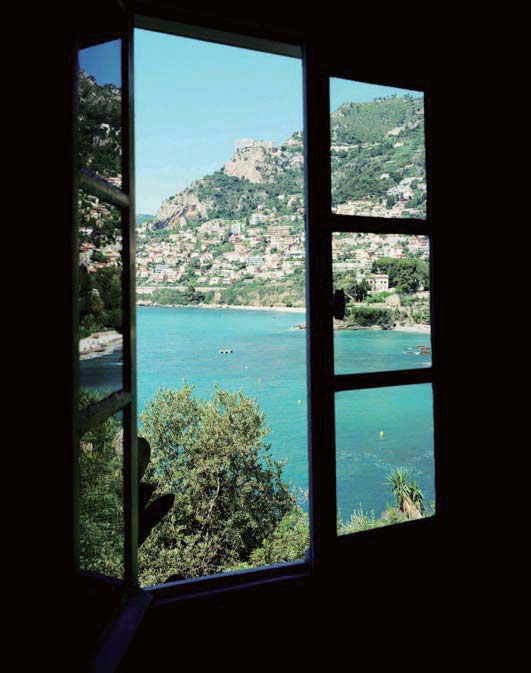

In the series entitled “A Song for Windows” (Libraryman, 2016), I photographed views of the surrounding scenery toward four directions seen from each of the windows at a cottage on a small island where Tove Jansson spent every summer [pict_08]. Recently, I am concentrating on photographing Le Corbusier’s windows, especially with a focus on views of outside scenery seen from the windows [pict_09].

-

[pict_08] Photo: Takashi Homma

-

[pict_09] Photo: Takashi Homma

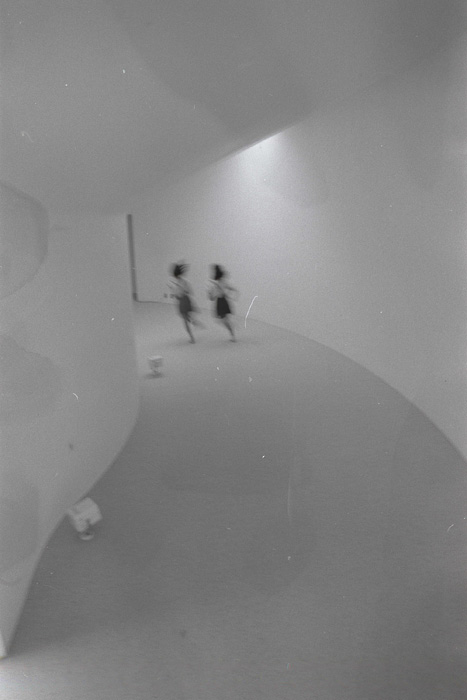

In recent years, I have been working on the “Pinhole” series using the camera obscura method [pict_10]. By opening a pinhole in the window in a completely blacked-out room, an image is projected on the wall opposite from the window. The image is projected onto a sheet of photographic paper to produce a photograph. To quote from the movie shown at the Windowology Exhibition, Hiroshi Hara said that “architecture is about opening a hole in a closed space.” In my opinion, it is exactly what a camera is about. That is, to think about window is to think about photography.

-

[pict_10] Photo: Takashi Homma

By the way, when I was invited to a radio show, I was asked to name “three favorite windows.” My answer was firstly the windows in the Convent of La Tourette by Le Corbusier, secondly the windows in Tove Jansson’s cottage, and thirdly the windows in the apartment building by Junzo Yoshimura. Actually, I have an office in this apartment building. It is a duplex type apartment and there is a skylight above the top of the stairs. On rainy days, I hear beautiful sounds of rain falling onto the skylight. I love the sounds, even though I know that Mr. Yoshimura’s original intension was to bring in natural light. Maybe we could make windows based on such idea.

Tsukamoto: I remember you said to me, which I think is an essential question, “How come architects don’t photograph architecture from inside even though they design the windows based on the idea of framing the view?” Later, I learned about your “Pinhole” series and understood what you meant by that.

-

From left: Igarashi, Baan, Tsukamoto, Homma

Once I assisted your Camera Obscura shooting of Empire State Building in New York––helped blacking out the room, counting exposure time and so on. This experience made me realize that photography is a physical activity. I think it is a great idea to combine a human body with the principle of camera now, when everybody can easily take photos using an iPhone. This idea may be applied to architecture as well. To think about windows is to think about the origin of architecture after all.

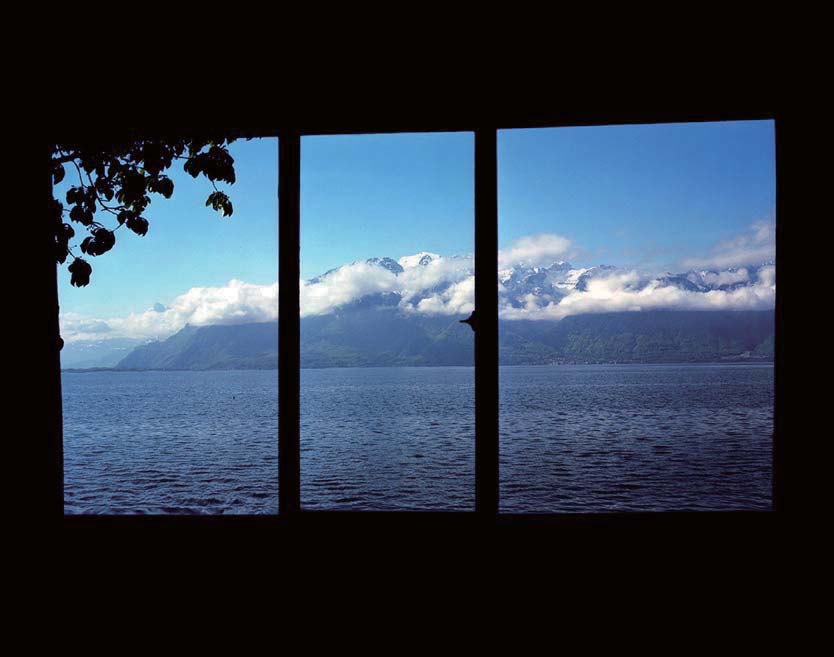

By the way, I visited Switzerland the other day. I came across a beautiful view of a lake and high mountains topped with floating clouds with the bottom stretched horizontally. They were exactly the same as the clouds in the scenery seen through the windows at Villa le Lac (La Petite Maison). It dawned on me that these clouds were perhaps the archetype of Le Corbusier’s ribbon windows [pict_11].

-

[pict_11] Photo: Takashi Homma

Relationship among Architecture, Windows, and Photography

Igarashi: What do think about windows when photographing architecture?

Baan: Now, as a photographer, the window is, of course, very important. It brings light into the building. It brings a sense of perspective. It also defines a space, to a great extent. But it also frames the views outside for me. The context and the location of the building are also very important for my pictures. That’s why I often also take these aerial photographs, where you can really see the city, but also when you’re inside the building and looking out. What I tried to show in my first examples, with the big commissions, are new architectural projects where the windows also become very important architectural elements that frame the city around them in a specific way, like you see in the work of Thomas Heatherwick, which reflects the city. So the window is a very important part of how you see a project, and how you experience the place.

Homma: Architecture photos impose some unspoken rules on photographers, demanding them to shoot in certain ways. But Iwan’s photos capture people lying down or eating inside Le Corbusier-designed architecture––they are among the most interesting photos I’ve seen for the first time in a long time.

-

Takashi Homma

Baan: For me, the people were always a very important part of the photographs, like with any place. My background lies more in documentary photography, and it’s still quite recent that I started to work with architects. I was always curious about how architects use people in their models, renderings, and all their presentations before a building is finished. Then, once the building is finished, they go and hire a photographer, and tell him, “You have to take that corner and that corner, and take all the people out.” These buildings were made for people. Especially when you look at older projects, like Brasilia and Chandigarh, it’s fascinating to see how people use these places, often in very different ways from how the architect envisioned the building at a specific moment, and how these projects slowly changed over time [pict_12].

-

[pict_12] Photo: Iwan Baan

At the same time, while I look at the higher profile projects, I also look at these self-built kind of nuts-and-bolts places. In the latter, the thinking about space is completely unconscious on the part of these people who have to just build a place by themselves. They all respond in a very specific way, depending on their environment and the materials that they find. And I find that they still end up designing a place in a very similar way to how architects think about spaces.

Homma: I went to shoot Shogin TACT Tsuruoka (designed by SANAA + Shinbo Architects Office + Ishikawa Architects Office) the other day. One of the architects told me to set my camera at the same level as the “eye level of perspective drawings.” I felt somewhat strange to be given instructions by the architect to shoot in the way as he likes (laughs.)

One of my favorite architecture photos is Koji Taki’s photo of White U (designed by Toyo Ito) capturing children running in the house [pict_13]. Iwan’s photos reminded me of this photo.

-

[pict_13] ©Koji Taki

Igarashi: Perhaps photographers bring out unique aspects of architecture that architects are unaware of. Now I would like to ask the last question. What are the most important points in deciding which architecture you photograph?

Baan: Yes. For me, the context is always important, not just the building. The context should be interesting. There should be an interesting other story to the architecture, to the place where it is located. This is a matter of framing, looking inside from the outside, but also the other way around, in terms of where the building sits in the city. It has to have a specific connection to a place. If it’s just generic architecture, it can be built anywhere, which is not so interesting for me. The story, on the other hand, is something that you try to bring out in photographs. That’s why people are also an important part of that story.

Homma: Koji Taki said, “One understands the architecture for the first time after living there for a while or visiting there several times.” I strongly sympathized with what he said when I stayed overnight at the Convent of La Tourette, and also the Unité d’habitation in Marseille. But at the same time, a photo automatically captures some image ––that is the essence of photography. I can shoot good photos in a quick shoot sometimes, but on the other hand, it is also true that I can achieve better qualities only when I stay there for a long time. I always have these thoughts in mind when I photograph architectural works.

Igarashi: How can photographers bring out the best in architecture by focusing on the world of windows? I am happy that today’s talk successfully indicated new possibilities of achieving this. Thank you very much.

Iwan Baan

Photographer. Born 1975 in the Netherlands. Graduated from the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague. Sought after by many architects, including Rem Koolhaas, Herzog & de Meuron, Zaha Hadid, Toyo Ito, and SANAA, for his ability to imbue their work with a sense of place and narrative. Awarded the Golden Lion (Best Project) in the International Architecture Exhibition of the 2012 Venice Biennale. His work has been published widely, including in the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, and Domus.

Takashi Homma

Photographer. Born 1962 in Tokyo. In 1999, he received the 24th Kimura Ihei Award for Tokyo Suburbia, a photo book focusing on landscapes in suburban Tokyo and the children who live in them. Held his first solo museum exhibition, New Documentary, in three museums in Japan from 2011 to 2012. Has published numerous photography books, including Tanoshii shashin: Yoiko no tame no shashinshitsu (Heibonsha), THE NARCISSISTIC CITY (MACK), TRAILS (MACK), Symphony – mushrooms from the forest (Case Publishing), Looking Through Le Corbusier Windows (Walther König, CCA, Window Research Institute). He is currently a visiting professor at the Tokyo Zokei University Graduate School.

Yoshiharu Tsukamoto

Architect, Atelier Bow-Wow. Professor, Tokyo Institute of Technology. Born in Kanagawa Prefecture in 1965. Graduated from Department of Architecture, Tokyo Institute of Technology (TIT) in 1987. Studied at Ecole Nationale Suprieure d’Architecture de Paris-Belleville (U.P.8) in 1987–88. Co-founded Atelier Bow-Wow with Momoyo Kaijima in 1992. Completed Doctoral Degree Program (Ph.D. in Engineering), Graduate School of Architecture and Building Engineering, TIT in 1994. Appointed Adjunct Professor, Graduate School of Architecture and Building Engineering, TIT in 2000 and currently serving as Professor at the school since 2015. Visiting Professor at Graduate School of Design, Harvard University in 2003, 2007, and 2016. Visiting Associate Professor at UCLA in 2007 and 2008. Visiting Professor at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in 2011–12. Visiting Professor at Polytechnic University of Barcelona in 2011. Visiting Critic at Cornel University in 2012. Visiting Professor at TU Delft in 2015.

Taro Igarashi

Professor, Tohoku University, Architectural Historian and Critic. Born 1967 in Paris, France. Graduated from the Department of Architecture in the Faculty of Engineering at The University of Tokyo in 1990. Completed a master’s degree at the university in 1992. Doctor of Engineering. Professor at Tohoku University. Served as the art director of the Aichi Triennale 2013 and commissioner of the Japan Pavilion for the 11th International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale and academic advisor of The Window: A Journey of Art and Architecture through Windows, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, 2019. Received the Newcomer’s Award of the 64th Art Prize of the Agency for Cultural Affairs. Books include Architecture After the Collapse of Modernism* (Seidosha), The Remarks of a Window and Architecture* (Film Art), and Beautiful Windows of the World* (X-Knowledge), among many others. (*Asterisked titles have been translated from Japanese)