Gordon Matta-Clark and Apertures

17 Sep 2018

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo is currently featuring the exhibition Gordon Matta-Clark: Mutation in Space. Matta-Clark graduated from Cornell University, where he had majored in architecture, and went on to become an artist, producing many experimental projects over a short lifetime. So what kind of a figure was this Gordon Matta-Clark? Focusing on the “apertures” in such works as Splitting—one of his definitive works which involved bisecting a house with a chainsaw—and Window Blow-Out, we asked chief researcher Kenjin Miwa, and Keigo Kobayashi, the designer of the exhibition’s venue who previously worked for OMA, to share their thoughts.

Exhibiting documentation

This exhibition is the first retrospective of Gordon Matta-Clark’s work in Asia. How did this come about?

Kenjin Miwa (hereinafter referred to as Miwa): To begin with, Gordon Matta-Clark had only been active as an artist for a decade or so when he died in 1978, at the age of 35. In his lifetime, it was only in the few years in the late 1970s that his name started to gain worldwide recognition. After his death, the full scope of his work became more apparent thanks to retrospectives in the 80s, 90s, and 2000s, particularly in the West. And these days, exhibitions of his work are held around the world on an almost annual basis.

And yet, Matta-Clark’s work has enjoyed little exposure in Asia, and there are few museums in Japan that own his work. So we undertook this project, working together with my co-curator Chieko Hirano of the University of Yamanashi, and with Foundation Gordon Matta-Clark. It’s taken about five years to prepare the exhibition, but here we finally are.

There’s almost nothing left now of the actual buildings that Matta-Clark cut. So if the cut buildings are the “original works,” then most of what is exhibited in the venue—footage, photographs, texts, what have you—are documentation of the works. So with a lot of it, it’s hard to determine whether it’s a work or a record. What’s more, most of his projects took place outside the confines of a museum. Given that it’s also the first large-scale exhibition of his work in Japan, this will be the first taste of his practice and expression for many visitors.

So we were concerned that if we just set up the usual white walls inside the exhibition space and arranged works along them, it would not allow people to actively engage with his work and his pursuits. There was always this question of how best to introduce Matta-Clark’s art in a museum, especially given that he is no longer with us.

-

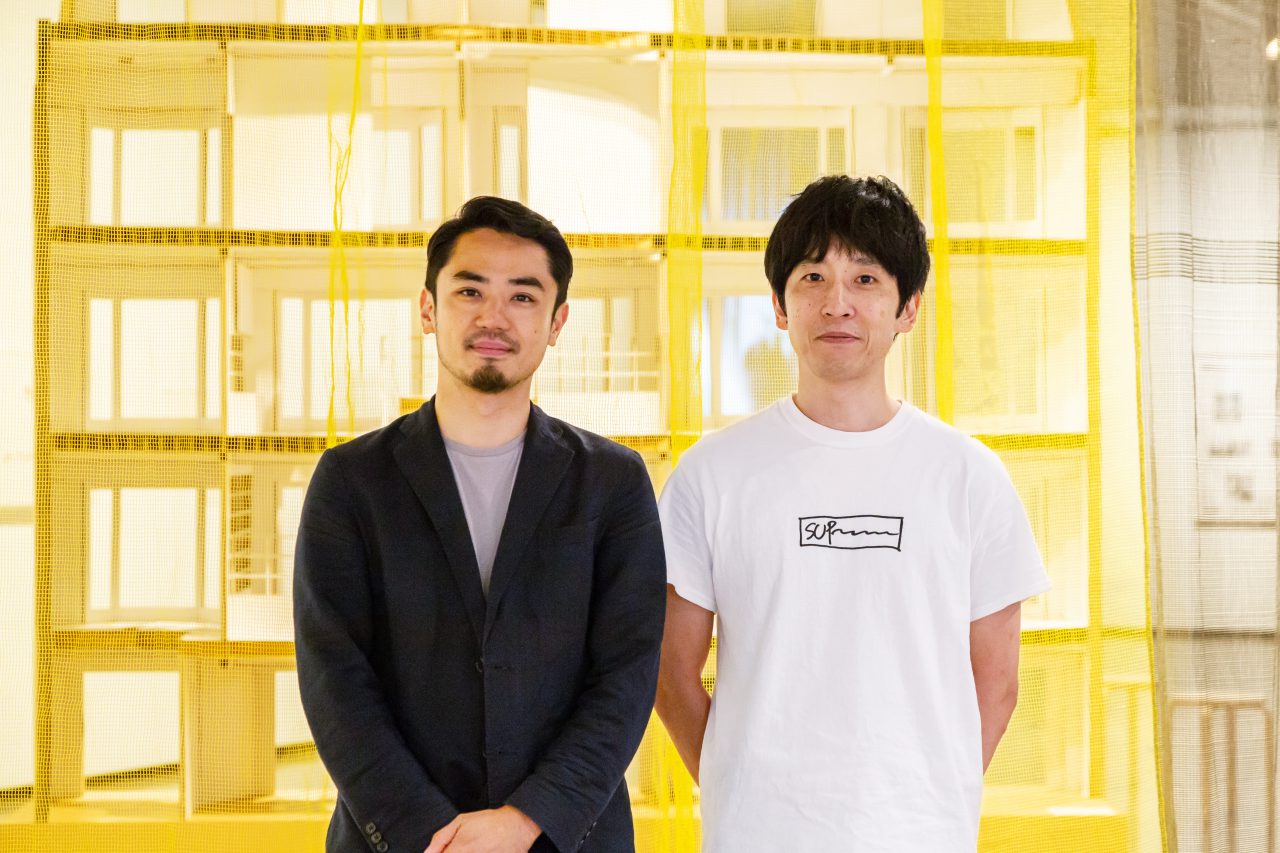

Venue of Gordon Matta-Clark: Mutation in Space Photography: Shu Nakagawa

-

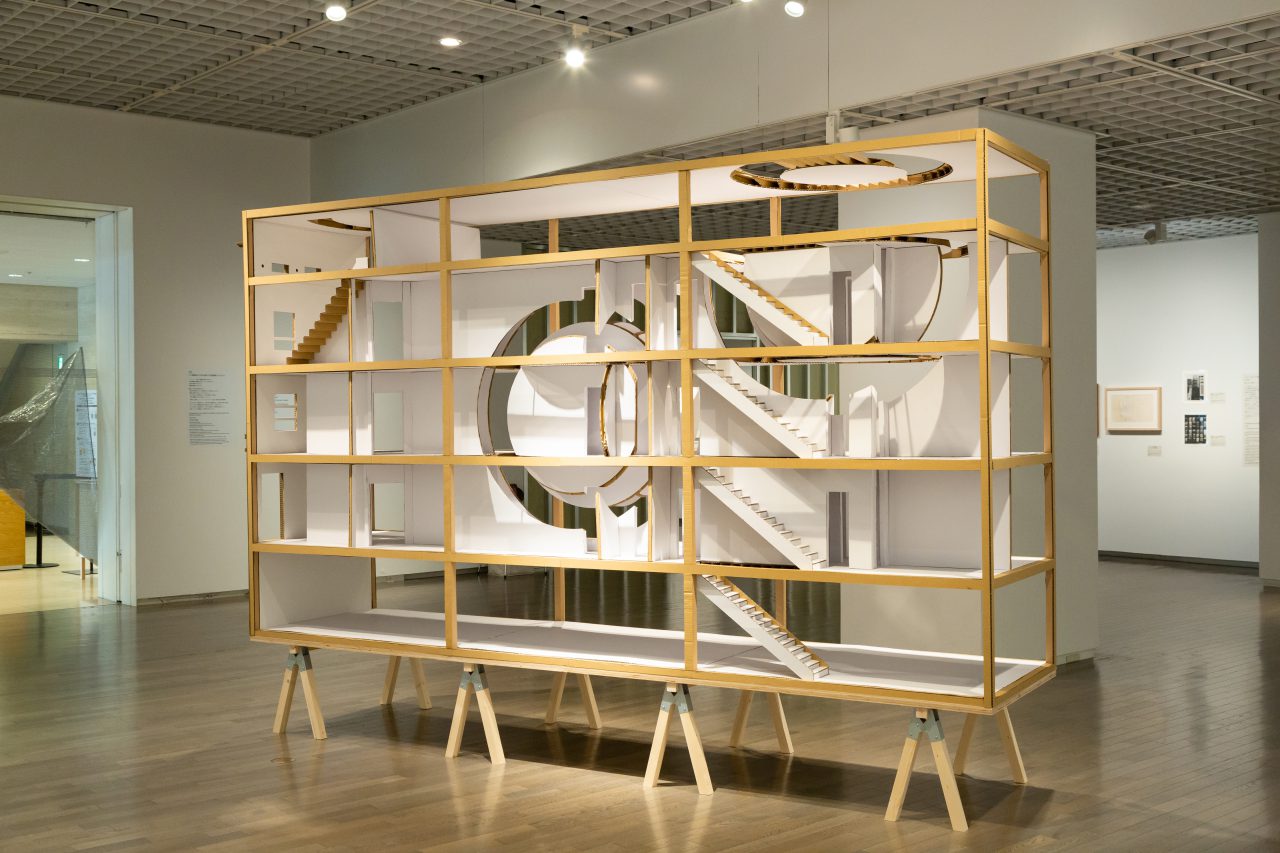

Circus or Caribbean Orange, 1978, Display model

We decided to ask Mr. Keigo Kobayashi, who’s an architect, to design the venue. One reason was that we wanted someone who had a real feel for what cities are like overseas, not just in Japan. Another reason for our choice was Mr. Kobayashi’s experience at Rem Koolhaas’s architectural design firm OMA, because Koolhaas was active in New York during the 70s, just like Matta-Clark.

Keigo Kobayashi (hereinafter referred to as Kobayashi): I’ve always been a fan of Matta-Clark, so I jumped at this precious chance. But I also felt some pressure, as many artists and architects have been influenced by Matta-Clark.

There’s a huge number of works and videos in this exhibition. So we arranged almost all of the most important works on the pre-existing outer walls of the exhibition space, so that you can at least see those works by walking along the perimeter. This way, the remaining space is freed from the constraint of displaying works. It also frees the visitors from having to worry about whether they’ve missed any exhibits. We thought that creating a space apart from the exhibition area would accord with what Matta-Clark attempts in many works, namely to shuffle the meanings of places.

Although the catalog refers to the venue as a “playground,” I see it more as a vacant lot with some building materials piled up. We designed the venue to be a space where visitors can act as they wish, sitting around or having fun.

Matta-Clark’s education in architecture

Miwa: You say that even in Japan, there are plenty of people working in architecture who are fans of or have been influenced by Matta-Clark. What do you think it is about him that appeals to them?

Kobayashi: Creating spaces is one important task of architecture, but another is intervening in spaces in order to change the meanings of places and environments, or to change people’s behaviors. In this light, much of Matta-Clark’s practice that doesn’t involve building does seem very similar to how an architect goes about thinking about space in a particular location.

After all, he studied on the architecture program at Cornell University, so he was more than familiar with all that. However far he might try to veer away from architecture, I think his ideas are still very much grounded in architecture. This makes him all the more interesting, because he has an architectural mind, yet doesn’t build—to put it another way, he achieves architecture without building. That’s what I find alluring.

-

Photo: Cosmos Andrew Sarchiapone © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark; Courtesy The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner, New York/London/Hong Kong.

So Matta-Clark studied architecture before becoming an artist.

Kobayashi: Yes—Cornell, his alma mater, has always been known as a top architecture school. The architectural critic Colin Rowe and architects like Richard Meier and Michael Graves—members of the so-called “New York Five”—were among the regular faces there in those days. These were the definitive New York architects of the time. But sometimes, it was precisely these people who were involved in the redevelopment of areas of New York that Matta-Clark chose for his work.

Miwa: Looking over past catalogs and literature, it seems that he graduated from Cornell with flying colors. But his widow Jane Crawford has said something like “his grades were good, but he got Ds in structures.” [laughs]

What is curious is that, even though he started out in architecture, he’s left very little in the way of plans and blueprints.

Kobayashi: It’s true. When I was doing the plan for the display model

based on photos of his building cut, I had the thought that if he had approached the work by drawing a proper plan then saying, “right, let’s do it,” I don’t think the work would have ended up like that. You can see it from the footage too, but he uses string and a pen to draw a line onto the building, then sets about cutting along it. He only holds back when there’s some part that would be a bit too risky to cut. The display model itself was barely supporting itself. Maybe those Ds in structures were actually an advantage there. [laughs]

Rem Koolhaas and 1970s New York

Mr. Kobayashi, you used to work for OMA. Is there anything that Rem Koolhaas and Matta-Clark have in common?

Kobayashi: Both of them studied architecture at Cornell, within a few years of each other. Koolhaas was there from around 1972, and Matta-Clark graduated in 1968. So they were not directly involved, but they were acquainted with mostly the same architecture crowd. Koolhaas was researching New York at the time too, so I think they had their eyes on the same world.

There’s a famous observation of Koolhaas’ about the Berlin Wall, which was his research area when he was a student. He points out that the mere presence of the wall gives rise to all manner of actions on both sides of the wall. For example, platforms spring up that allow people to see family members on the other side, or children play games that involve the wall, or people tie string to the wall and hang their laundry. He observes that one wall has the result of drawing out people’s actions and behavior more than architecture does—that a building is in fact more limiting than you might think, that you can do a lot more where there aren’t any buildings. So Koolhaas too had such opinions, at least at one stage.

-

Mr. Keigo Kobayashi

I think there’s a resemblance there to Matta-Clark’s “anarchitecture.” The idea of architecture adding meaning to the incomplete, to absence, is common to both Koolhaas and Matta-Clark. I was strongly aware of this connection when planning the design of this venue.

Still, Koolhaas is an architect, so he has to build buildings as an architect. Speaking in terms of Matta-Clark’s “building cuts” series where he cut holes into buildings, those excisions can’t be made without a base structure, a structural frame. The difference is that Koolhaas builds the structural frame first, then integrates emptiness into the architecture. So their practice is contrastive in that sense, but I feel that their starting point—their foundation—are very similar.

Do you think that New York was a special place for both of them?

Miwa: Matta-Clark lived in New York for a long time including his childhood, so the city would have meant a lot to him. His sphere of activity expanded after the mid-70s as he was invited to exhibit in Europe more frequently. But his projects before then were primarily based in New York. I get the feeling that his actions and expressions were grounded in New York.

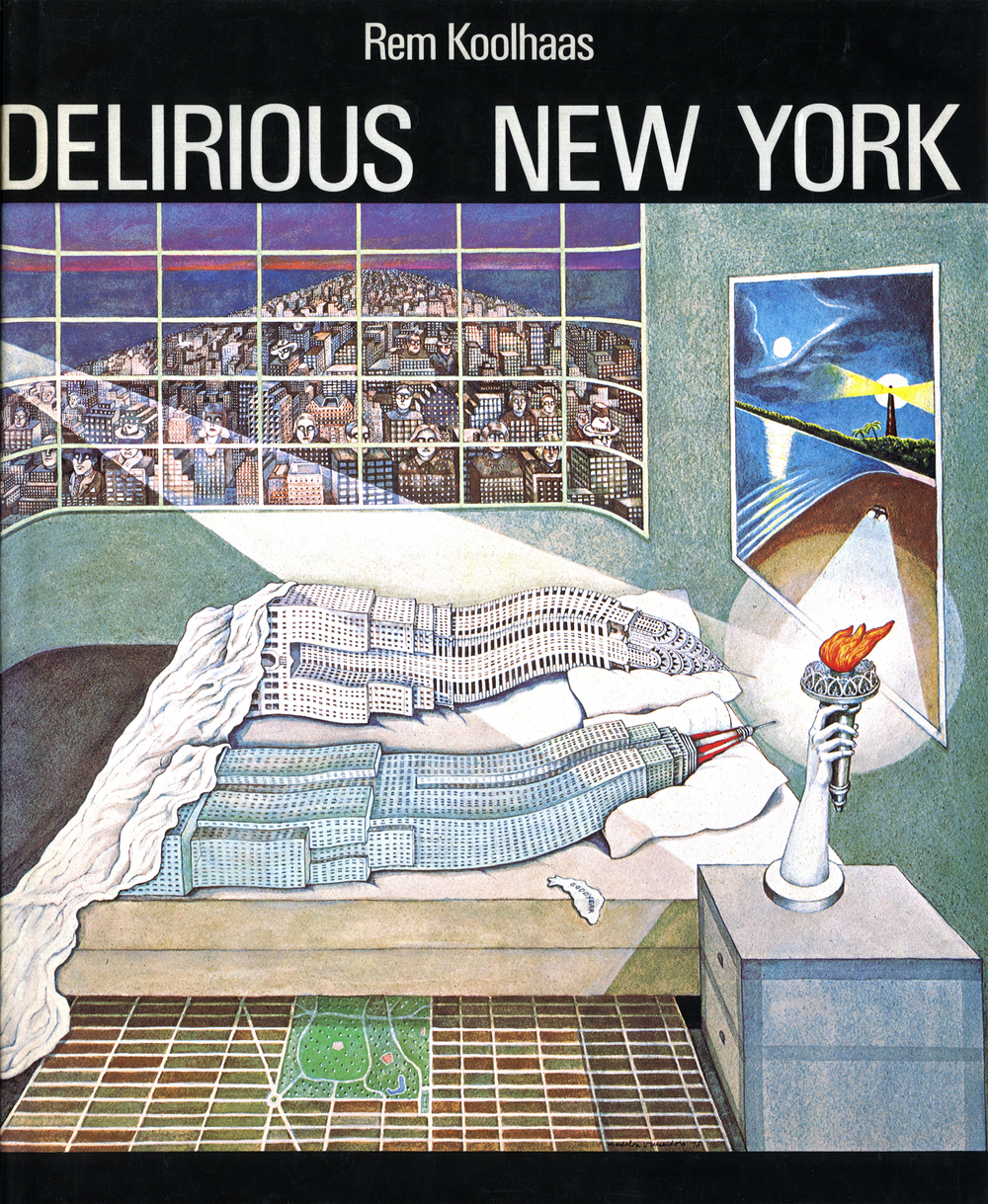

Kobayashi: In Koolhaas’ case, he was fascinated by Manhattan’s capitalistic growth—he even uses the term “Manhattanism” in his book Delirious New York. Matta-Clark was more anti-capitalist in a sense. He directed his attention on the situation in the suburbs and the Bronx, which capitalism had thrown into turmoil. So strictly speaking, there seems to be a slight difference in where their interests lie.

-

Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York (1978). Illustration by Madelon Vriesendorp.

For example, Koolhaas was researching New York as part of the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies (IAUS), a Manhattan-based think tank founded by Peter Eisenman, who was one of the New York Five. Matta-Clark was invited to exhibit in its Idea as Model show (1976), but he proceeded to respond with the very antagonistic expression of Window Blow-Out, in which he smashed all the windows in the space, much to Eisenman’s exasperation. While Matta-Clark took an extremely critical stance against the social trend, Koolhaas watched the capitalist condition and its rapid growth, and found interest in its excesses. In that way, their approaches are polar opposites.

Miwa: IAUS was located opposite the New York Public Library, around West 40th St. That’s right at the heart of Manhattan.

If you map the sites of Matta-Clark’s projects in New York, you find that he’s done very little around Midtown Manhattan. I think it’s interesting how most of his projects were in peripheral areas of New York: places like Brooklyn and the Bronx just off Manhattan, and Staten Island further south, which used to be a landfill. Window Blow-Out is a bit of an exception, though it was likely because he had been invited to exhibit there. Although it does make me wonder why he didn’t do anything in Central Park.

Kobayashi: That’s a good point.

Miwa: Maybe he didn’t choose the central district because there wasn’t much there that he could respond to. There are few places with enough room in which to intervene.

-

Mr. Kenjin Miwa

Window Blow-Out

There are a number of works by Matta-Clark that revolve around windows, including Window Blow-Out.

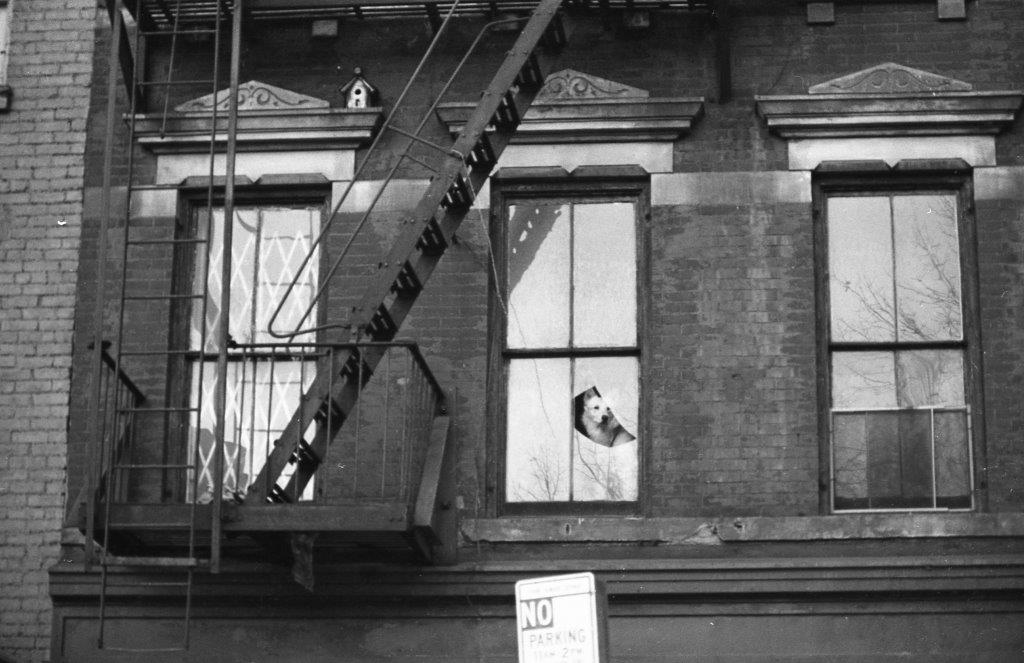

Miwa: That was a work that Matta-Clark produced in 1976 for the Idea as Model exhibition, for which IAUS had gathered architects and artists. It consists of photographs of smashed windows in places like the Bronx and Brooklyn.

The photographs show not only old buildings, but also relatively new buildings like high-rise apartments. At the time, redevelopments were progressing at an astonishing pace, forcing low-income residents out of the area. So when you see new buildings with broken windows, it’s because the old residents who were kicked out would break them by throwing stones and so on.

Kobayashi: The windows in this work fall into a number of categories. There are those like the windows in old disused buildings in South Bronx, then there are windows of newly developed buildings that were just mentioned. Then there are the windows in the actual exhibition space in central Manhattan where the IAUS exhibition took place. They all appear similar: glass panes inside a window frame. But their functions and their buildings’ significances are all different. Add to that the fact that the windows are broken, and their significance really begins to vary.

-

Window Blow-Out, 1976 © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark; Courtesy The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner, New York/London/Hong Kong.

-

Window Blow-Out, 1976 © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark; Courtesy The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner, New York/London/Hong Kong.

For example, the smashed windows of the exhibition space were a statement of sorts that he was making against IAUS; with the South Bronx windows, he seems to have been focusing more on a derelict city awaiting development. The windows of newly developed buildings might have been from the viewpoint of those who had been kicked out of their homes. I think it’s fascinating how this common element of the window becomes a device that accentuates these differences of meaning. Even the same action of smashing windowpanes might bear a different meaning in every photograph.

Wordplay and thought processes

“Anarchitecture” is a prime example, but the way in which he tweaks words and phrases—like “Form Fallows Function”—is very interesting.

Miwa: Matta-Clark coined a lot of curious neologisms by punning on or combining pre-existing words. He made some 200-odd cards that are referred to as “art cards,” from which you can tell that he was consciously trying to use words as triggers for developing new ideas.

He didn’t leave behind much in the way of essays and discourses. I think that uses of language like wordplay or poetry suited the pace of his thinking process better than essays, which require more time.

-

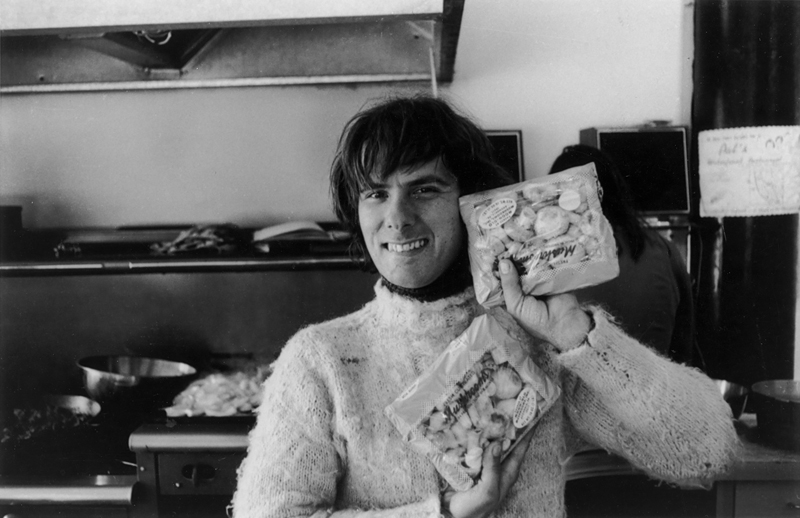

Gordon Matta-Clark with camera at FOOD, 1971-72 Photo: Cosmos Andrew Sarchiapone © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark; Courtesy The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner, New York/London/Hong Kong.

If you watch footage of FOOD, the restaurant he was running with his friends, you’ll see that he’s always joking around, including that kind of wordplay. [laughs] According to then-girlfriend Carol Goodden, with whom he was running FOOD, he would speak in a way that hopped from topic to topic. The links would be totally lost on the listeners, who would be like, “What’s this guy on about?” But as you got to know him better, you realized how it was all connected, how these conversational leaps eventually ended up back on the original thread.

Given how varied his projects were in style and approach—and all this in a career that lasted just shy of a decade—his thought processes don’t seem to have been the sort that developed chronologically or progressively.

Take the word “non-u-ment,” which is his word for a “counter-monument.” When you actually delve into it and try to define it clearly, you realize it’s actually quite vague.

In the 1960s and 1970s, art was expected to be conceptual and logically coherent, and artworks that were not so would often be criticized for being “sloppy.” But when it comes to Matta-Clark, I feel that qualities like the certain lightness of his work, or his use of language that prompts instant reactions in others, should be regarded as positives. Though, of course, we must look carefully at the thought that underlies this lightness.

Kobayashi: I agree. These phrases are almost just silly puns or “dad jokes,” and not what one would expect from his actions. There’s a lot of intent and thought involved, but he kept all that to himself rather than force it down people’s throats. I think he consciously chose not to offer complicated explanations of his works’ meanings.

-

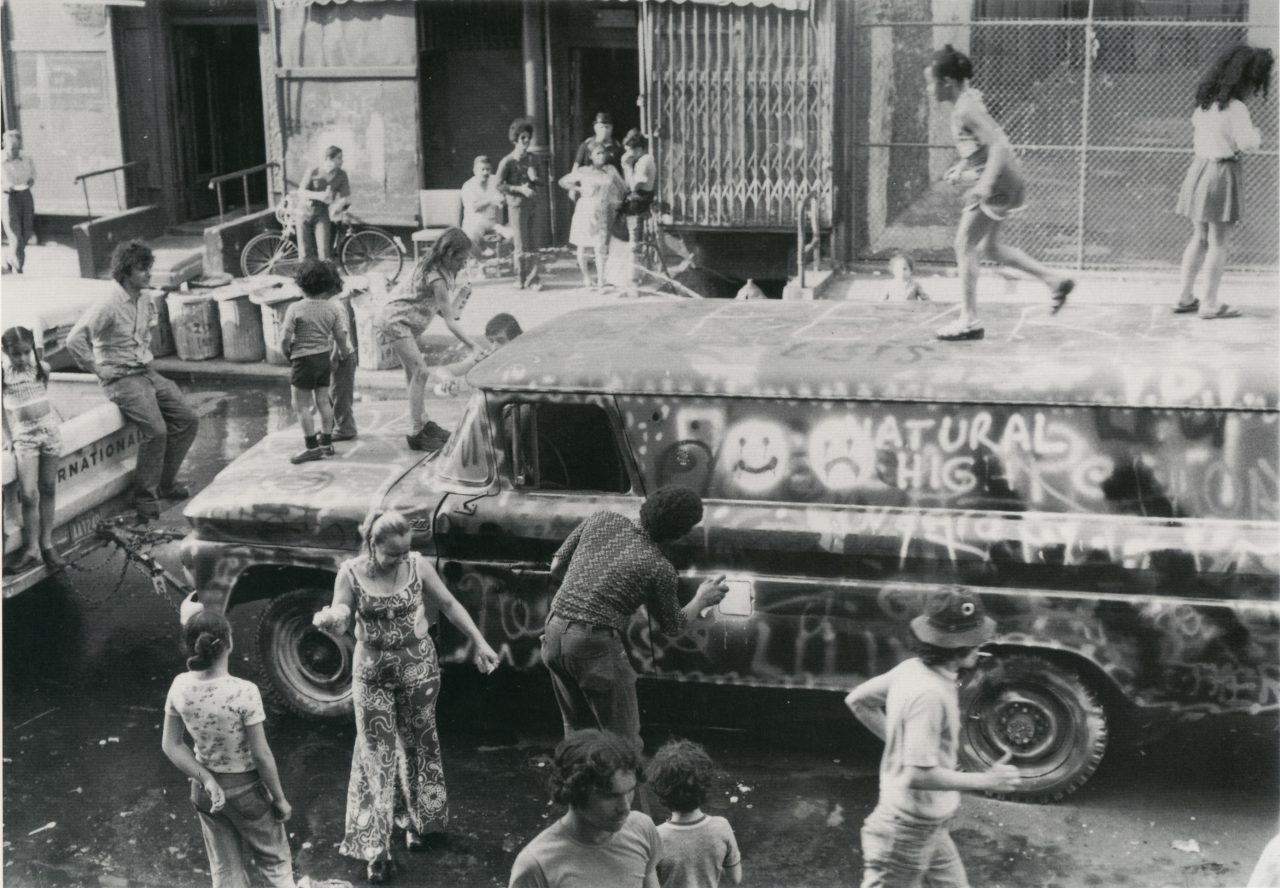

Graffiti in progress on the Graffiti Truck, 1973 © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark; Courtesy The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner, New York/London/Hong Kong.

By doing this, he invited the public—ordinary people – into his art. I think that’s how he preserved the freedom and breadth of interpretation. This goes for this exhibition too. I think the power of Matta-Clark’s work is that even people who don’t know much about him can come and go away satisfied, with the impression of a man who was doing something quite out of the ordinary. I think wordplay was a very appropriate way to maintain this breadth.

He also loved things like paradoxes. Wordplay has the ability to take words that are seemingly unrelated or even contradictory, and reconcile them with a bit of thought. In terms of architects, he shared something with Takamasa Yoshizaka, who also uses words a lot when trying to come up with architectural ideas.

Miwa: Co-existence of two contradictory elements is a characteristic of Matta-Clark’s work. Depending on which of the two the viewer reacts to, the assessment might be one that even the artist himself had not foreseen. The idea that destruction is a form of creation also has this co-existence.

One example is a work called Conical Intersect staged in the building next to the Centre Pompidou, which was still mid-construction at the time. This area, which had been the site of a market called Les Halles, was being redeveloped at the cost of the old townscape. As a critique, he made conical holes in two of the last old buildings remaining. But this was met with criticism at the time.

Though supposedly against the development, the work had destroyed surviving buildings by carving holes in them, and so was seen by some to have been the final nail in the coffin. This pained the sensitive Matta-Clark.

-

Conial Intersect, 1975 © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark; Courtesy The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner, New York/London/Hong Kong.

Splitting

“Building cuts” like that, where he cuts through or cuts holes into parts of buildings, are one of his most famous series. What kind of process did Splitting involve?

Miwa: Splitting was staged in Englewood, New Jersey, which is a thirty- or forty-minute drive from Manhattan, over the Hudson River. There was a house there that was going to be dismantled due to redevelopment, which they told him he could use for an artwork. So that’s how he came to make Splitting, a work in which he cut a building cleanly in two. The neighborhood was already full of vacant lots and abandoned houses, like the one used in the work.

The building cuts mainly targeted places that had fallen off people’s radars and were just slowly falling into decay. Matta-Clark carved holes in such buildings, bringing light into them once more. The popular interpretation is that by intentionally cutting holes in places that would not have seen light when the buildings were occupied, he sought to give these spaces new life. The inversion of the relationship between inside and outside is a characteristic method in his work, not just the building cuts.

-

Splitting, 1974 © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark; Courtesy The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner, New York/London/Hong Kong.

-

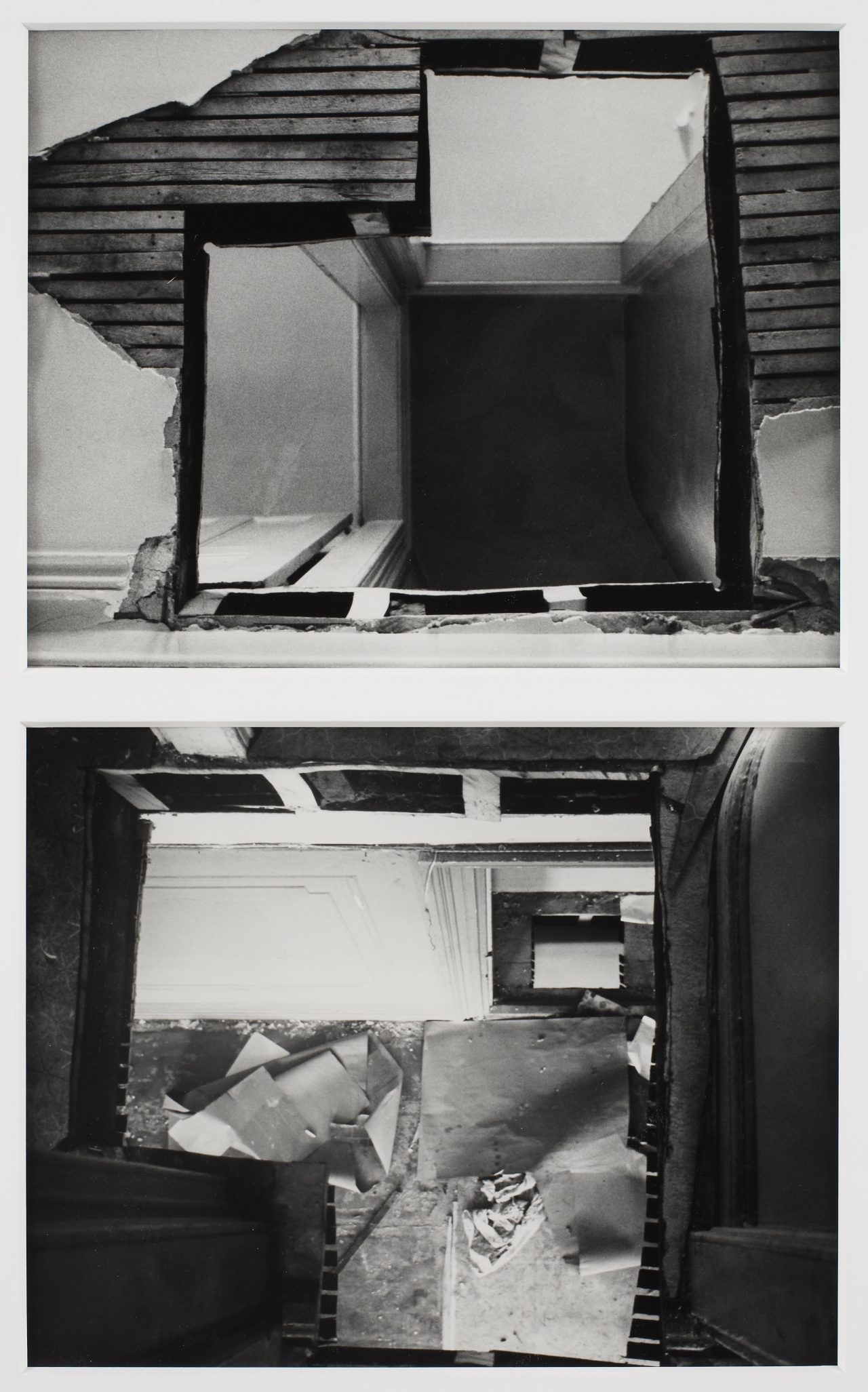

Splitting Four Corners, 1974

Kobayashi: Particularly in this case, this was a very typical house with a gabled roof (two sloped sides with a triangular top), and the windows emphasized its “houseness.” I think, for him, these windows were less apertures, and more an element of the house form. I assume that his action of cutting and opening this house form arose partly from his skepticism about people being stuck in their suburban homes, or being forced to live in constraining circumstances. But I think it also shows a critical attitude to the very idea of the house, which is, so to speak, a machine in which to live.

What’s interesting is that the original apertures with window frames are seen alongside the four-sided apertures that Matta-Clark cut out. The usual meaning of windows and that of the holes that he cut out become indistinguishable when they are arrayed next to each other. It’s hard to say to what extent he saw the pre-existing windows as apertures, but the work does seem to be a bold expression of this relationship, in which the emergence of these holes raises questions about the meaning of windows and apertures.

Miwa: That applies not just to the inside and the outside, but to the upper floor and the lower floor too—to the vertical relationship. There’s a work in the Bronx Floors series where he deliberately takes the threshold between rooms and cuts out the floor/ceiling, connecting the upper and lower floors.

Kobayashi: By having those holes there, the adjacent rooms that were originally connected and the rooms in the floors below all become one, sharing the same floor and ceiling. So his work connects all these spaces while cutting them up. I think that’s one of the exciting things about the building cuts. In that sense, the series really captures the power of windows, which goes beyond merely opening and closing.

-

Bronx Floors: Double Doors, 1973 © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark; Courtesy The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner, New York/London/Hong Kong.

One memorable aspect of the Splitting footage is the people experiencing the work by the aperture.

Kobayashi: This applies to some of anarchitecture’s slogans too, but the notion of incompleteness or disruption creating interest was something that really resonated with me. We had this in mind when designing this exhibition’s venue too, which is why we did things like intentionally leave surfaces unfinished or use flooring material for the wall. The idea was that leaving things incomplete might actually make it easier for people to get involved.

In this sense too, I think that the reason Matta-Clark went about destroying and cutting things that were complete was an attempt to create such room for the imagination to come in. It’s also fascinating to watch in the Splitting footage the people who have come to see the work. You see them jumping over the aperture, standing on the edge and looking down, or looking up and playing. The work allows people to intervene physically in the work too. It achieves both these things at once. So his apertures produce a kind of margin that allows people to engage. This is an aspect that really appeals to me as an architect.

Day’s End

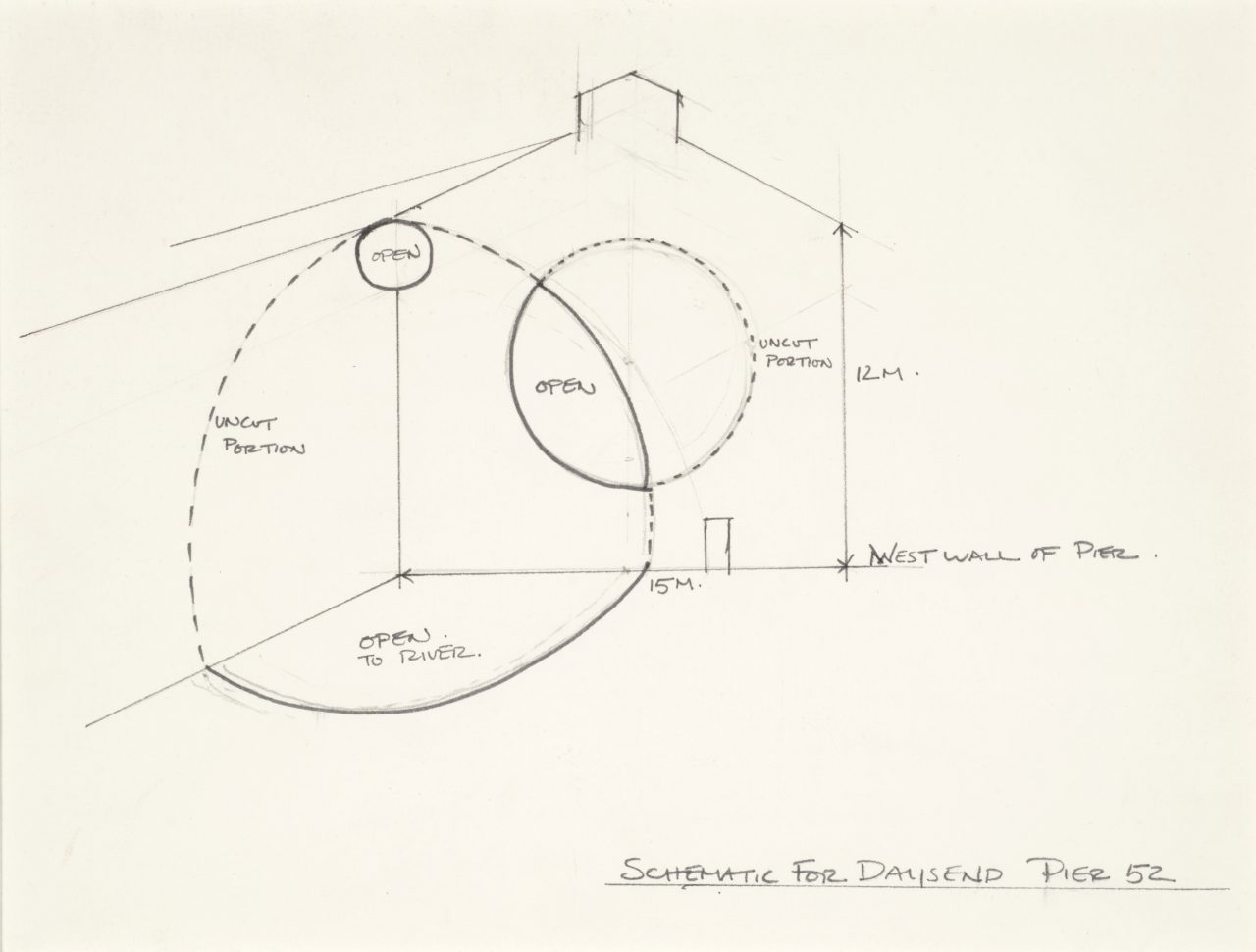

Matta-Clark apparently referred to the aperture in Day’s End, which was staged in a disused warehouse on a dock, as a “rose window” (circular stained-glass window mainly seen in medieval Gothic architecture), likening it to a Christian basilica.

Miwa: The warehouse was originally used by a railway company. Mr. Kobayashi, did it feel to you like a church when you saw it?

Kobayashi: I can certainly see the analogy. Buildings like the basilica that you see when you go somewhere like Florence are also boxlike constructions with wooden crossbeams. The proportions are probably very similar.

-

Day’s End, 1975 © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark; Courtesy The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark and David Zwirner, New York/London/Hong Kong.

Miwa: Matta-Clark hadn’t obtained permission for this work, and the police suddenly showed up on opening day, so he was never able to present the work properly to the public. But he described it figuratively as “a sculptural festival of light and water” and “an enclosed park.” He seems to have planned for it to be a public place like a park, where people could come and spend some time.

Kobayashi: It would have been a place where people who were in a sense alienated by the city would find themselves at home. Creating an aperture in such a place and presenting it as a cathedral seems conceptually fitting.

He also designed the shape of the window in relation to the sun’s path, taking the environment into account. You see that kind of thing in contemporary architecture, but there were few people back then with ideas like that. When the sun comes in from the west, an oblong light is projected on the opposite wall. It’s fascinating how he properly considered the relation between the aperture and the sun. He cut through the floor too, so depending on the angle of the sun, light would be reflected in the rippling water under the deck. This variation in how light shows itself is very “architectural,” so to speak.

-

Schematic for Day’s End, Pier 52, 1975 Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal / Gift of Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark; CourCanadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal.

Did Matta-Clark produce the work singlehandedly?

Miwa: He had help from multiple friends for this work. Such a collaborative process is a feature of many of his projects. In one photography exhibition called the Anarchitecture Show (1974), they even had multiple artists all exhibiting their work anonymously. So, to an extent, I get the impression that he did not consider an artwork as the undertaking of one artist, as something to be credited to a singular name.

Contemporary Tokyo and Matta-Clark

The exhibition flier has the tag line: “He was everyone’s idol.”

Miwa: Drawings were really the only things that Matta-Clark produced all on his own. As we said earlier, the other works were mainly created together with those around him. He was always surrounded by friends, curators, supportive gallerists and so on. He was at the center of this group, always half a step ahead of everyone else. I believe there was a general pattern in which Matta-Clark would find something new, then everyone else would respond to it.

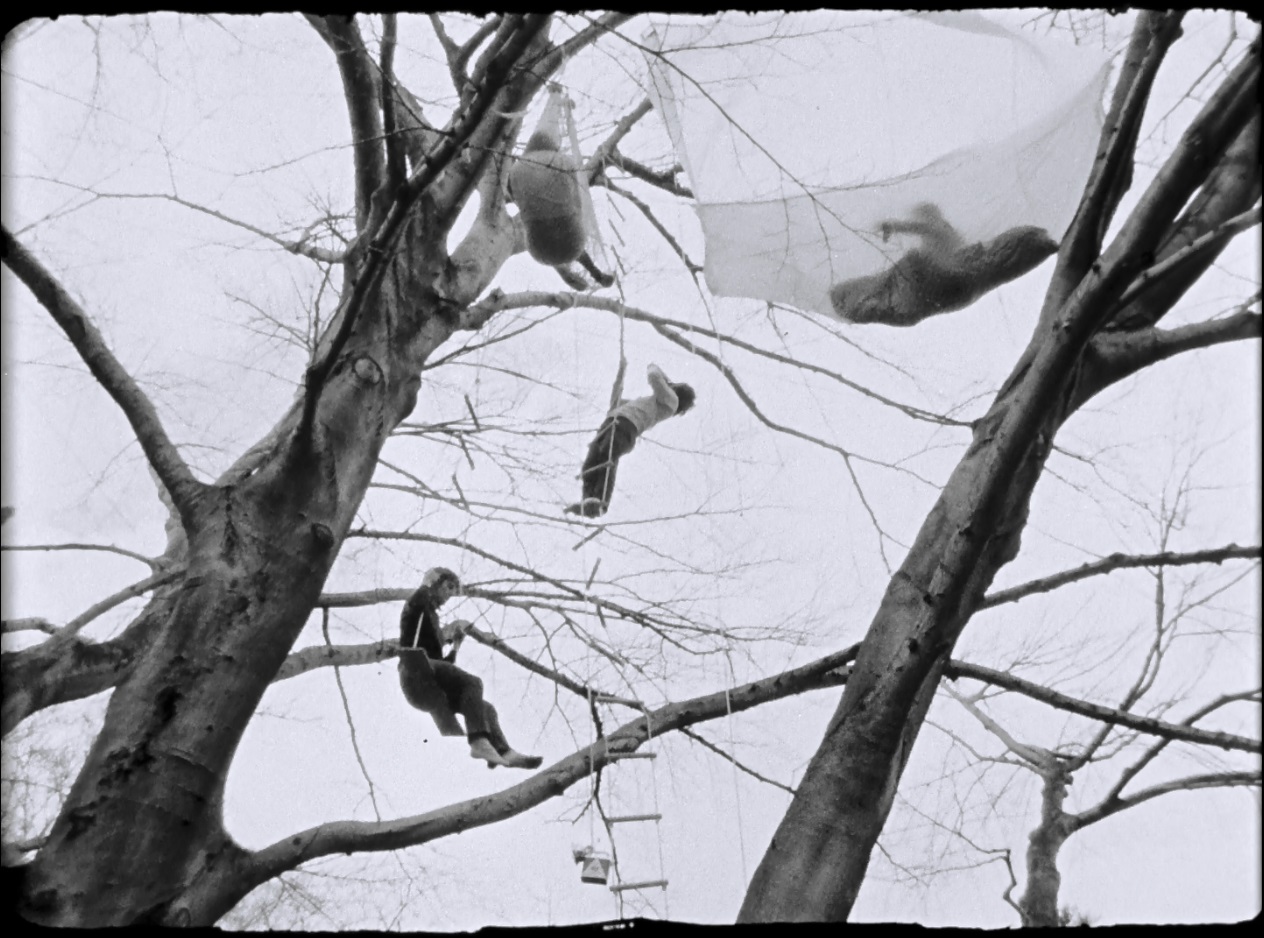

Kobayashi: With FOOD too, if he had done it as a one-day event and succeeded in getting the idea across, it would still have constituted a work. But what made him brilliant is that he actually ran it as a restaurant for some years, remaining involved in the project. With Tree Dance too, he said that he would have liked to stay up in the tree for longer. I get the sense that the way people got involved was as important to him as the works themselves.

-

Tree Dance, 1971 © The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark; Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

In what ways has Matta-Clark been influential?

Miwa: His works like the building cuts are, of course, referenced in art and architecture at a formal level. In other fields too, it often happens that his ideas—whether they were ever realized or not—serve as inspiration for others, sometimes undergoing various “misreadings.” Gordon Matta-Clark’s work has “room” for people of different fields to react, and to relate it to their own work. The lightness of his works and this “room” that it affords will always attract people. I think that’s the kind of artist he was.

Kobayashi: After seeing this exhibition, people might come across a tree and see it as a potential place to live, or see a step and think of sitting or lying there. I think his work offers such new perspectives on the city. And that sort of influence is something that extends beyond the field of art or architecture.

Miwa: I hope that this exhibition will be a starting point—or maybe even the first half-step—to that realization that Mr. Kobayashi just talked about.

Kobayashi: I think 2018 was the perfect timing to put on this exhibition in Tokyo. It’s only now, when people have finally started to argue that architecture isn’t just about building, that Matta-Clark’s ideas coincide with those of architecture. And he was putting this into practice 40, 50 years ago. I find this enormously encouraging.

Today, Tokyo is no longer undergoing fervent development and expanding endlessly. But diminishing would mean that the question of how to connect people and connect places will become an even more salient theme. And if so, I feel that the methods by which Matta-Clark sought to build such connections are particularly suited to today’s Tokyo.

There’s also his ability to convert paradoxes into energy. To penetrate to the essence of the contradictions that exist in the city of Tokyo, while maintaining a certain humor too—that sort of approach is one that I want to learn from and draw on as an architect. If you’re overly serious, you’re going to have trouble winning people over, so the question is how to incorporate humor. It’s not something that the Japanese are terribly good at, but I think that’s why it’s all the more appealing.

Kenjin Miwa (right)

Miwa is chief researcher at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (MOMAT). His curated (and co-curated) projects include Re: play 1972/2015―Restaging “Expression in Film ’72” (2015), 14 Evenings (2012), and Waiting for Video: Works from the 1960s to Today (2009), all at MOMAT. His recent writings include “Nonsite—Death Valley” in The Works of Robert Smithson: From Plastics (1965) to Nonsites (1969) (MOMAT, 2017).

Keigo Kobayashi (left)

Kobayashi is an architect and associate professor of Waseda University. A graduate of Waseda University and Harvard University, Kobayashi worked at the Rotterdam office of Rem Koolhaas’ architectural firm OMA/AMO from 2005 to 2012. He was involved in various key projects there, including large-scale architectural projects and urban planning projects in the Middle East and North Africa. In 2014, he designed the exhibition in the Japan Pavilion at the 14th Venice Biennale. He co-founded the architectural practice NoRA in 2017.

Exhibition: Gordon Matta-Clark: Mutation in Space

Venue: The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

Dates: June 19 (Tue), 2018—September 17 (Mon), 2018

http://www.momat.go.jp/english/am/exhibition/gmc/