Of Homes and Windows in the 20th Century: In Conversation with Ken Tadashi Oshima, the Curator of Living Modernity: Experiments in Housing, 1920s–1970s

27 Jun 2025

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Exhibitions

- Interviews

In the twentieth century, as waves of modernization swept across the globe, the home became a site of architectural experimentation—an arena in which new ways of living were imagined, constructed, and contested. The exhibition, Living Modernity: Experiments in Housing, 1920s–1970s, now on view at the National Art Center, Tokyo, revisits this pivotal half-century, examining the social, technical, and aesthetic roles that modernist housing came to play.

How did architects respond to the wide-ranging challenges of their time? We spoke with Ken Tadashi Oshima, an architectural historian and guest curator of the exhibition, to explore this question.

In this exhibition, the relationship between modernity and the home is a central theme. How did you go about structuring the project with that in mind?

Twenty-five years ago, I co-edited the two-volume special issue, a+u Visions of the Real: Modern Houses in the 20th Century (Shinkenchiku-sha, 2000), and re-examined classic modernist houses through new photography and site visits. This provided a real sense of experiencing these spaces, and not simply a historical perspective. The 2025 exhibition builds on this approach, however, shifts the focus to reexamining the design problem of the house, as explored by Le Corbusier, to understand how the fundamental aspects of living and modernity shape everyday life and reflect broader societal and technological shifts from the 1920s to the 1970s.

The exhibition explores seven themes—hygiene, materiality, window, kitchen, furnishings, media, and landscapes. What led you to focus on these specific areas?

One major challenge in addressing modernity was hygiene—creating healthy environments in response to diseases such as tuberculosis. Architects such as Le Corbusier and Adolf Loos considered plumbing not only as a technical necessity, but also as a broader design concern.

Therefore, materiality has become important. Steel and glass, along with traditional materials such as bricks and tiles, were reconsidered to create spaces suited to modern living. Fundamental design elements—windows connecting the inside and outside; kitchens designed for efficient food preparation and casual dining; and furniture, lighting, and textiles shaping everyday experiences—were central to the Bauhaus ethos. This integrated approach to living extended beyond individual houses. Photography and exhibitions helped to communicate what modern living could be and promoted the underlying design philosophy.

The media played a role in spreading these ideas, while landscapes shaped the fundamental relationship between a house and its surrounding landscape, which remains relevant today, particularly when considering sustainability issues.

By examining these different aspects, we can observe how designers have addressed these problems in connected or contrasting ways. This study may offer lessons for contemporary architects and people by considering how we may live in the future.

-

Interior view of the kitchen in Casa de Vidro (Lina Bo Bardi, 1951). Featuring an open layout that connects the dining area to the garden, with a pizza oven installed in the backyard—outdoor dining was integrated into everyday life. Photo ©︎ Nelson Kon

-

Interior view of the kitchen in the Tsuchiura Kameki House (Kameki Tsuchiura, 1935). Designed with a focus on efficiency, it features thoughtful circulation, a serving hatch, and task lighting—elements that reflect a functionalist approach reminiscent of the Bauhaus. Photo ©︎ Tomomasa Kusunose

Did 20th-century architects design these houses to meet social needs, such as the Spanish flu pandemic and industrial advances? Or were they primarily shaped by new technology?

Each architect may have approached this differently, however, they all grappled with the challenge of designing for health and well-being. As we witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic, it was a time of exploration without a clear answer from the outset.

For example, Alvar Aalto designed Paimio Sanatorium (1933) to maximize sunlight in Finland, where winters are quite dark. In the summer, the days are long and sunny. The use of terraces for direct exposure to the southern sun, reflective qualities of white surfaces, and materials such as ceramics or porcelain for tiles and sinks all became essential. In his Muuratsalo Experimental House (1954), the emphasis shifts slightly; while there is a white brick enclosure for the courtyard, the focus is more on how sunlight interacts with materials and influences mood in living spaces.

This highlights both the physical and scientific aspects of creating healthy spaces as well as the psychological aspects of feeling comfortable and promoting well-being. The way light is reflected within a space, how air and light enter through windows, and framing contribute to a sense of home and healthy living. These elements operate on multiple levels.

-

Interior view of the living room in the Experimental House in Muuratsalo. Photo ©︎ Shinkenchiku-sha

Moreover, examining Pierre Chareau’s Maison de Verre (1932) is interesting because the owner was a doctor. The clinic on the ground floor made health and cleanliness central concerns. The use of glass blocks for window walls, originally designed to allow light to pass through sidewalks, was revolutionary. The way light interacts with them is almost magical; it is not only about the blocks themselves but also the square forms and circular lenses within them, creating a crystalline refraction effect.

I was fortunate to have visited it some years ago, and the transition between dusk and evening struck me the most. When the exterior lights were turned on, the manner in which the glass blocks captured light transformed the interior space at night, offering a completely different perception of the space.

They almost resemble shoji screens, although on a vastly different scale. Moreover, it raises the question of whether it is a window or a wall. It is solid yet allows light to pass through. This translucency is a defining feature of space. While other windows in the house have clear glass panes that allow airflow, these glass blocks significantly affect the interior experience at different times of the day.

-

Exterior view of the Glass House. Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Georges Meguerditchian / distributed by AMF

This highlights the importance of focusing on the window problem, as the Window Research Institute does. Rather than treating windows as an afterthought in design, they should be viewed as central to how spaces function and to the overall experience of a building.

How did the perception of windows and their role in hygiene evolve throughout the 20th century, as demonstrated in the exhibition?

In January, I visited the Frank & Berta Gehry House (1978) from outside and closely observed their windows. Some original windows from the 1920s Dutch Colonial house remain, however, in extending the house toward the street, Gehry integrated windows both on the walls and as skylights, using low-cost two-by-four wood framing. This design creates a sculptural interplay of light while serving practical needs such as ventilating a centrally placed stove with an operable window.

-

Interior view of the kitchen in the Frank and Berta Gehry House. Photo ©︎ Tim Street-Porter

The windows serve multiple roles—airflow, ventilation, and light—while also breaking from strict geometric modernism in favor of a freer composition. This contrasts with Pierre Koenig’s Case Study House #22 (1960), which builds on Mies van der Rohe’s modernist houses, such as the Tugendhat House (1930) and the Farnsworth House (1951). However, in Los Angeles, where casual indoor-outdoor living is common, it assumes a new character, making large sliding glass windows feel almost expected.

By this later period, such designs were less revolutionary, however, remained fundamental to how these houses functioned. A key question in analyzing these windows is whether they are solid, transparent, or open. Glass can reflect or allow direct visibility, however, this shift depends on the lighting conditions, particularly from day to night.

Mies extensively explored these material qualities, including how glass reflects and changes throughout the day. I found architect Kishi Waro’s impression of the Farnsworth House particularly interesting; he was surprised by how solid the glass appeared, almost similar to a stone, making it difficult for him to perceive in person. It is far less transparent than expected from the photographs.

Photographs often suggest a level of openness that is not fully realized in person. Although the visual aspect is important, the real impact emerges from how air moves through the space and how the window shapes the overall experience, something that can only be understood in terms of physical presence.

Which works have you focused on in developing the concept of the window as a frame for indoor-outdoor living, as presented in the exhibition?

In my opinion, all architects consider windows as both a fundamental design element and a way to integrate technology into the homes.

Le Corbusier is an essential reference point, not only for his use of the horizontal window at Villa “Le Lac” (1923), but also for his approach to openings in stone walls and how they frame the landscape. In contrast, we can consider Mies van der Rohe and his famous Tugendhat House, where some of the windows retract into the floor. The entire glass wall in the living space can disappear into the ground, completely transforming the interior into an exterior space with airflow. I believe this is truly magical.

-

Interior view of the living room in the Tugendhat House. Two central glass panels are operated by an electric mechanism and retract into the floor. Photo ©︎ Halvor Bodin

During my research on Mies in the late 90s, I was fortunate to experience this at an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. Observing the window descend into the floor and how dramatically it altered the perception of the inside and outside was impressive. Today, this type of feature may be expected in many designs, however, at the time it was incredibly modern and innovative.

In contrast, we can observe how much Mies’ vision of architecture—his use of glass— inspired others. For example, Lina Bo Bardi’s Casa de Vidro (1951) was inspired by Mies, however, shaped by the landscape of São Paulo, Brazil. Moreover, it employs simple technology to create a direct connection between the window and view. Initially, the surroundings of Casa de Vidro were open; however, vegetation grew over time, with many palms transforming it into an almost jungle-like environment. The evolving landscape has profoundly shaped spatial experience.

-

Interior view of the living room in Casa de Vidro. Photo ©︎ Nelson Kon

The exhibition interconnects themes such as windows in the landscape, hygiene, and materials, illustrating how they shape modern living.

Le Corbusier, Mies, Fujii, and Bo Bardi showcased the diverse uses of glass. Window proportions: Full-height, waist-level, operable, or fixed-effect spatial experience.

Louis Kahn offered another contrast in the perception of windows. His Fisher House treats the window not only as a visual opening, but also as a mechanism for modulating airflow. I wrote about this in Jutaku Tokushu, September 2024 Issue (Shinkenchiku-sha, 2024). The recessed window allows cooler air to enter naturally. Unlike Le Corbusier’s brise-soleil, which relies on louvers to regulate sunlight, Kahn’s recessed windows are passive ventilation systems.

The famous window seat in the Fisher House (1967) integrates furniture, landscape, and lighting, shifting in scale depending on the viewer’s perspective—sitting, reclining, or approaching. To help visitors fully grasp this experience, the exhibition features a full-scale mockup of the window, as photographs alone cannot fully capture its three-dimensional qualities.

An interesting detail noted by Galen Minah, a colleague who worked with Kahn, is that the bench’s backrest folds down to reveal a hidden TV—an elegant integration of modern living needs into architectural design.

-

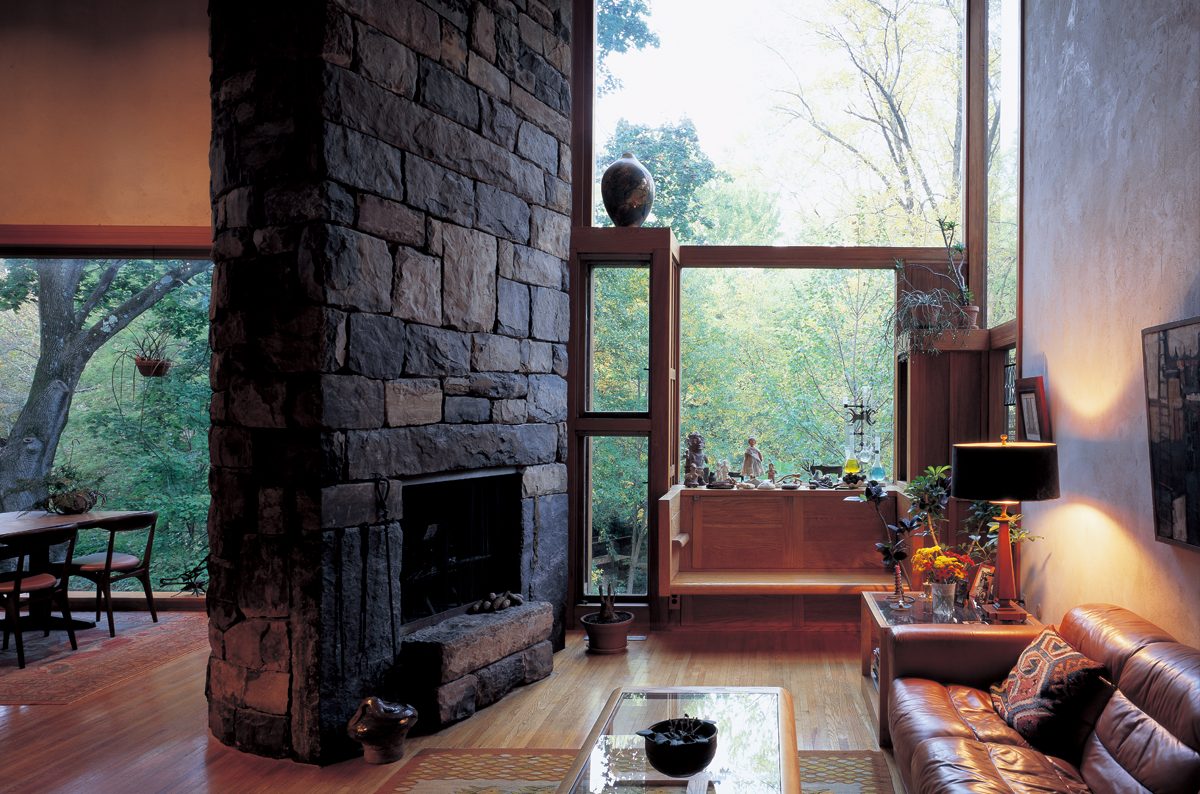

Interior view of the living room in the Fischer House. Photo ©︎ Shinkenchiku-sha

From your discussion of Fisher House and Gehry House, it is clear that windows serve various functions, such as ventilation and lighting. In modernist architecture, was Louis Kahn the first to approach windows in this manner, or were there earlier influences?

The development of windows in the Fisher House by Louis Kahn is noteworthy. Based on my colleagues’ recollections of Kahn’s process, this study builds on the Eshrick House (1959-1961), which also had vertical windows and shutters. However, in the Fisher House, the window is integrated with the bench, becoming an element of furniture; with Kahn, this idea has evolved.

It is not part of the exhibition, but the a+u issue featuring Balkrishna Doshi’s own house, illustrates how he integrated lessons from Le Corbusier and Kahn in the context of Ahmedabad, India. The intense sun plays a crucial role, influencing not only the windows and shutters, but also the flooring. For example, dark-slate flooring helps create a cooler and more comfortable space.

We observed the evolution of these ideas across different contexts through various architects. For example, Le Corbusier explored this between Europe and America with the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts (1963), but also in India, where houses such as the Shodhan House (1951-56) and the Sarabhai House (1955) in Ahmedabad demonstrate the importance of brise-soleil in response to climate change. Adapting to the environmental conditions is central to this approach.

Further, there is the question of how many architects lead the process by incorporating existing technology. Whether a window is a casement or sliding, or, in the case of Frank Lloyd Wright, how it functions both decoratively and physically in shaping space, these elements continue to evolve.

I am excited to observe how the twenty-first-century window will shape house design in the future and how the relationship between manufactured and designed windows will shape the future.

Do you notice any notable differences in how windows are used in Japan compared with other countries?

The concept of the modern house can be observed in the classical paradigm of Katsura Villa (c. 1615–1620), which embodies modernity in its openness between the inside and outside. Shoji and other sliding panels create frames while maintaining airflow, making them fundamentally open.

Similarly, in houses such as Koji Fujii’s Chochikukyo (1928), Kameki Tshuchiura’s Tsuchiura Kameki House (1935), and particularly the Sky House (1958) by Kiyonori and Norie Kikutake, we observe this interaction between the interior and exterior.

For example, Chochikukyo reflects the Japanese tradition of openness through sliding panels, while incorporating specific openings for air circulation. The careful proportioning of glass panes deliberately frames views, merging traditional dwelling concepts with modernist evolution.

The house was published in both Japanese and English, illustrating its design through drawings and climate analyses. This combination of technical and visual perspectives is fascinating.

-

South-facing exterior view of Chochikukyo. Photo ©︎ Shinkenchiku-sha

In Sky House, sliding panels regulate light and air, creating wide openings, reminiscent of Kikutake’s traditional houses and temples. This period witnessed a hybrid approach to openings and windows, challenging the notion of solid walls.

This raises an interesting question: Does the window hold more significance in framing the view from inside to outside or vice versa? The answer varies, reflecting different dwelling traditions and historical contexts. Perhaps this dialogue between Japan and the broader world helps to shape a deeper understanding of the window’s role in architecture.

Despite the experimental approaches adopted by these architects, this exhibition sought to re-examine the challenges faced by these houses. What key issues emerged from this research?

It is interesting to examine these windows in the context of the time and technology available, in terms of glass size, single-pane construction, or glass type. Today, with advancements such as double- and triple-pane glazing, architectural possibilities are fundamentally altered. Maintenance is one of the challenges associated with these windows. Often, they are replaced; however, it is difficult to match the exact proportions of windowpanes or find hardware that is no longer produced.

For example, at the Walter Gropius House (1938), restoration was extremely expensive because many of the original windows were no longer in production. Sourcing hardware and fittings from antique stores or refabricating special pieces became necessary.

This raises the key question of whether to maintain the original windows with the same glass scale or adapt them to modern needs, such as double- or triple-pane glass, for the current energy codes. Each decision involves different considerations.

Inevitably, houses change their windows over time. However, returning to the fundamental question of how we view and experience the landscape and considering it on both conceptual and practical levels remains important.

By examining these examples, I expect you can appreciate them on dual levels.

Today, standardized windows are commonly used in homes worldwide, particularly in Japan, leading to a loss of individuality in window design. What can we learn from this exhibition about rethinking window design?

However, this question remains complex. We observe many windows that are produced industrially. I have incorporated them into my own house and constantly contemplate how to update the windows. However, if I were to convey a single message, it would be how important it is to question the window. In architecture school, one of my instructors asked, What is a window?—a rhetorical question with no fixed answer. Is it a “wind eye”? What is its function? Is it conceptual or physical?

By examining this question in detail, we acquire a deeper understanding of dwellings and how they relate to our environment. Among the different elements highlighted in this exhibition, windows are central.

-

Interior view of the living room in Villa Le Lac. Photo ©︎ Shinkenchiku-sha

I am pleased to have this conversation, as the exhibition begins once you step inside, and the entire first level is framed by the horizontal window of Villa “Le Lac” in its proportions. I believe this hints at the exhibition’s message while emphasizing the importance of considering dwellings in these particular ways.

LIVING Modernity: Experiments in the Exceptional and Everyday 1920s-1970s

Period: March 19 (Wed), 2025 – June 30 (Mon), 2025

Venue: The National Art Center, Tokyo

Opening Hours: 10:00-18:00 (Fridays and Saturdays, 10:00-20:00) *Last admission 30 minutes before closing

Admission (tax included): 1,800 yen (Adults), 1,000 yen (College students), 500yen (High school students)

Website:

https://www.nact.jp/english/exhibition_special/2025/living-modernity/

Ken Tadashi Oshima

Oshima is a professor in the Department of Architecture at the University of Washington, where he teaches in the areas of transnational architectural history, theory, representation, and design. He has been a visiting professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and has taught at Columbia University and the University of British Columbia. His articles on the international context of architecture and urbanism in Japan have been widely published and he has been an editor and contributor to Architecture + Urbanism for more than a decade.