The Windows of the Diffendorfer Memorial Hall and University Chapel at the International Christian University (ICU): Preserving, Passing On, And…

28 Aug 2024

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Columns

- Essays

- Japan

The International Christian University’s campus plan was originally designed by W. M. Vories & Co. and later developed by Antonin Raymond. The Diffendorfer Memorial Hall and University Chapel, which both underwent extensive renovations when passed on from Vories to Raymond, can still be seen standing at the heart of the campus. Researcher Yu Kishi delves into the history of these two buildings by focusing on their windows.

Introduction

Taking a rapid train on the JR Chuo Line from Shinjuku, you will arrive at Musashisakai Station after about 30 minutes. Transfer to the bus bound for “Kokusai Kirisutokyo Daigaku”, and stay on board for about 10 minutes until the last stop. Stepping off, you will see the University Chapel, marked by the cross on its façade, beyond the main entrance roundabout. As you get closer, another building will come into view behind it. This is the Diffendorfer Memorial Hall (referred to hereinafter as the “D Hall”). The two buildings, standing almost at the exact center of the campus, serve as focal points at the end of the avenue extending in a straight line from the main gate. The International Christian University (ICU) campus in Mitaka, Tokyo, was established on the former site of the Nakajima Aircraft Company Mitaka Research Institute. The University Hall, now housing classrooms, is known for having been converted from a research building to an academic building. The campus plan was initially designed by W. M. Vories & Co., but Antonin Raymond was called upon to finalize it during the brief period after Vories retired in 1957 due to illness.

-

The Diffendorfer Memorial Hall (right) and University Chapel (left), connected by a walkway.

The Chapel, built in 1954, was designed by W. M. Vories & Co, as was the D Hall, built behind it in 1958. Later, in 1959, the Chapel underwent an expansion (completed 1960), resulting in its current appearance. The expansion project was conducted by the Raymond Architectural Design Office. DOCOMOMO Japan listed the D Hall in 2017 and the Chapel in 2020. A year later, in 2021, the national government designated the D Hall as a tangible cultural property.

The D Hall and Its Windows

The D Hall, which faces the University Hall across a lawn, is a work of modernism characterized by exposed cast-in-place concrete slabs and large glass windows on all but the curved portion of its north-facing front façade. In plan, it forms a hollow square, housing an auditorium on its north side and a student lounge, a kiosk, the administrative office of the church, and rooms for student cultural clubs on the south side.

Details about the construction of the D Hall can be found in Kenchikuka Vōrizu no ʻyume’ [Architect Vories’ Dream] (Benseisha Publishing, 2019). As explained in this book, ICU’s founders seem to have requested Vories to design a modernist-style building that would befit the newly established postwar Japanese university. Perhaps they saw modern architecture, with its emphasis on maximizing economy and efficiency in construction, as the optimal choice given the financial situation of the fledgling institution. Vories assigned the project to Izumi Katagiri, a junior member of his staff. Katagiri also worked on the design of the Omi Brotherhood Building in Ochanomizu, Tokyo, around the same time.

-

East elevation of the D Hall.

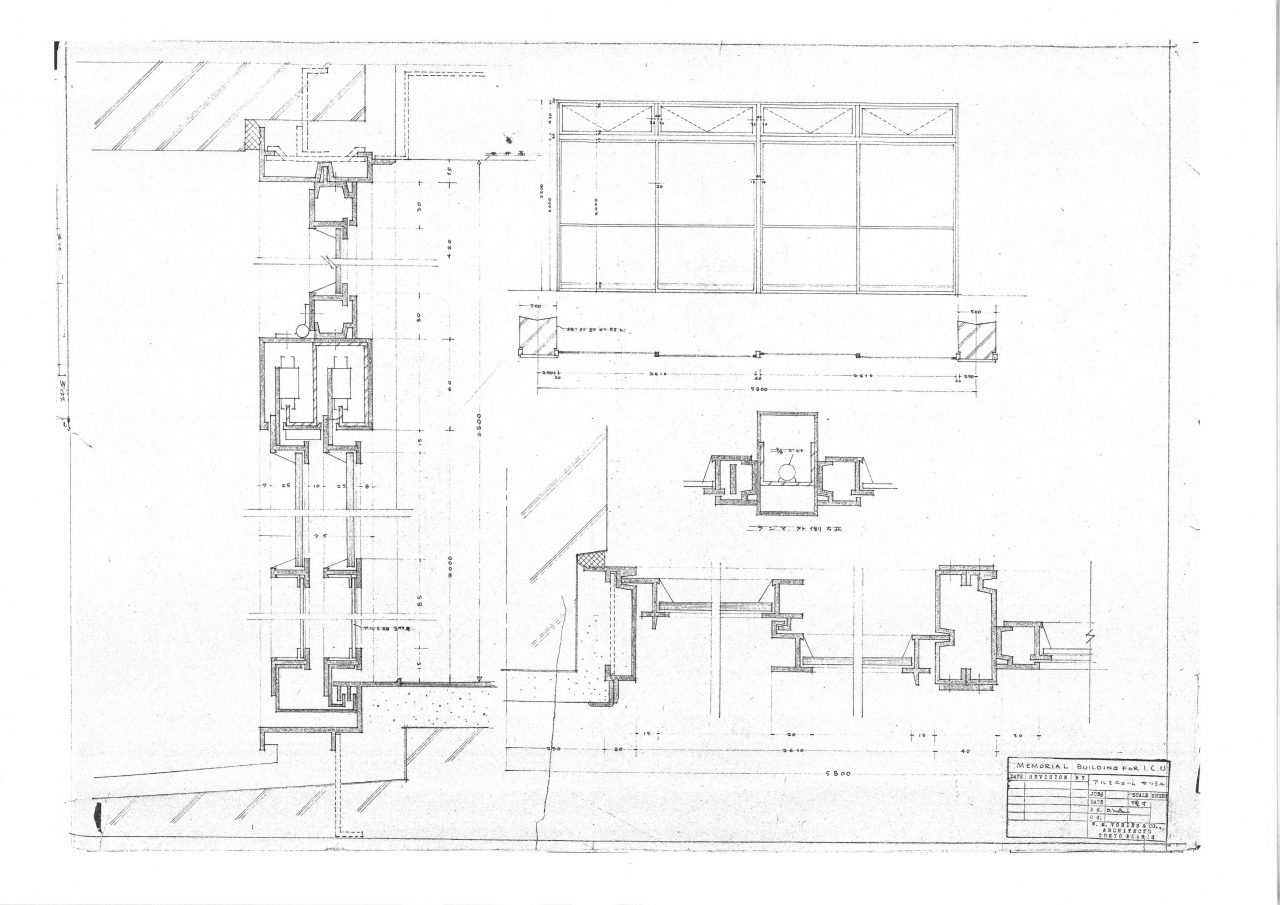

A key point to note regarding the D Hall’s windows is that some of the original aluminum sashes from 1958 are still in use. Domestically manufactured ready-made sashes for buildings first became available on the market in 1959. Therefore, the D Hall’s old sashes are made-to-order components. These were cast rather than extrusion molded, as is commonly done today. The windows consist of double-sliding windows and transom hopper windows, with steel reinforcement integrated within the transoms and mullions to make their faces appear thinner. The thin frames and muntins, along with the muntins set at a low height to align with the perimeter railings, contribute to the clear, open views.

The D Hall underwent two extensive renovations after 1958. Notably, the renovations of 2021 saw the building systems updated with the installation of a decentralized HVAC system and elevators. Some of the partition walls were removed to accommodate these changes. The treatment of the window sashes became a major point of contention during this renovation. While many of the original sashes remained intact, there was dissatisfaction among users concerning their performance, as they did not open and close properly and provided little airtightness. Consequently, the sashes in the more frequently used spaces on the south side were replaced, and those in areas with particularly high historic value, such as the north side of the first-floor student lounge and auditorium foyer, were left untouched. The renewed south-side sashes hold a single pane with faux muntins added to maintain continuity with the original windows. The transom hopper windows were also changed to double-sliding windows. Although this resulted in the use of wider elements, the layout of the lites was matched to that of the originals.

-

The renewed aluminum sash windows.

The University Chapel and Its Windows

When originally completed, the Chapel had a rose window and triple arches on the front, and its exterior and interior surfaces were largely unified in a cream color. A bell tower was planned but was not realized due to budget constraints. Raymond’s expansion project saw the building almost entirely redesigned, except for the structural members, the side exterior walls that project towards the front gable end, the narthex, stairs, and second-floor gallery. The overall design was unified mainly in the color of the concrete, and the nave was extended westward by four spans. A walkway and bell tower were added to the north side. On the front façade, a large portico was added, and a cross was set between new pilasters positioned over the concrete expansion joints, emphasizing the verticality of the façade.

-

The east-facing front façade of the Chapel.

Inside the Chapel, the walls and ceilings, which presumably were still the same cream color as the exterior walls prior to the expansion, were covered with plywood. The way the zigzagging planes of the side walls continue onto the ceiling brings to mind the St. Anselm Church in Meguro, Tokyo. What appear to be triangular piers from the inside, however, are actually part of the thickened interior walls. The ceiling, resembling a folded plate roof, is made of plywood suspended from steel trusses. In 2001, the uppermost parts of the clerestory windows were fitted with jalousies.

-

Interior view of the front end of the Chapel.

-

Light shines in from the slits in the zigzagging wall.

In addition to the color of the finishes, the windows contributed greatly to the Chapel’s changed appearance pre- and post-expansion. Before the expansion, the Chapel had a rose window on the front and clerestory windows between the bays. After the expansion, the rose window was filled and replaced by the cross, and the side windows were reoriented and reshaped into slits by adding the angled walls. The glass fitted in the aisle windows is painted with stained-glass-like patterning, likely the work of Noémi Raymond. The paint was applied after the patterning was etched onto the surface of the glass.

-

The painted aisle windows. -

The designs are presumably based on biblical motifs.

The Coexistence of Vories’ and Raymond’s Designs

Noting his impressions of the ICU campus, Raymond writes that it was “vast, both in scale and setting”, yet “everything was informed by goodwill and frugality” and “dominated by a missionary air, unheeding of the bigger picture”. In his eyes, Vories’ Chapel was stylistically “colonialist”, the D Hall was “semi-modernistic, like something designed by architecture interns”, and the campus as a whole was a planless assemblage of “haphazardly arranged” buildings, the result of “a disorderly and timid effort”. In Vories’ defense, there did exist a campus plan, and it was being developed with consideration of the client’s demands and budget. As Vories writes, “before all else, we must take interest in the education itself, and we must design the buildings to truly fit their educational purpose”, and he sought to do so while staying true to his motto of “achieving the maximum effect with minimal spending”.

-

North façade of the Chapel.

As evidence of this, the north walkway connecting the Chapel and D Hall, realized by Raymond, for example, was already part of Vories’ master plan. One could thus say that Raymond merely executed what Vories had originally planned. In fact, ICU, the client, also views Vories’ work as Phase I and Raymond’s work as Phase II of its campus project. One can even imagine that Raymond gave the Chapel its concrete-colored exterior walls with articulated joints as a reference to the D Hall with the aim of harmonizing his addition with the adjoining building.

Conclusion

The fact that Vories and Raymond, a seemingly unlikely pairing of architects, converged through these works of modern architecture, offers a glimpse into the situation surrounding the development of modernism in postwar Japan. If the professional duty of an architect is to give their all towards fulfilling the requirements presented to t, then it could be said that both did so in their own ways, successfully achieving the “maximum effect” in response to their client’s demands. The ICU campus is the only place in Japan where one can see Raymond and Vories’ work standing side by side.

Yu Kishi

Born 1980 in Sendai, Miyagi, Japan. Completed a doctorate in comparative culture at the International Christian University. PhD. Specializes in modern Japanese history and modern Japanese architectural thought. Currently teaches as an adjunct lecturer in Tokyo. Board member of DOCOMOMO Japan and Access Point Architecture-Tokyo. Co-author of Kenchikuka Vōrizu no “yume”. Translated books include White Walls, Designers Dresses by Mark Wigley.