How Technology Changes the Future of Windows

06 Sep 2016

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Design

- Interviews

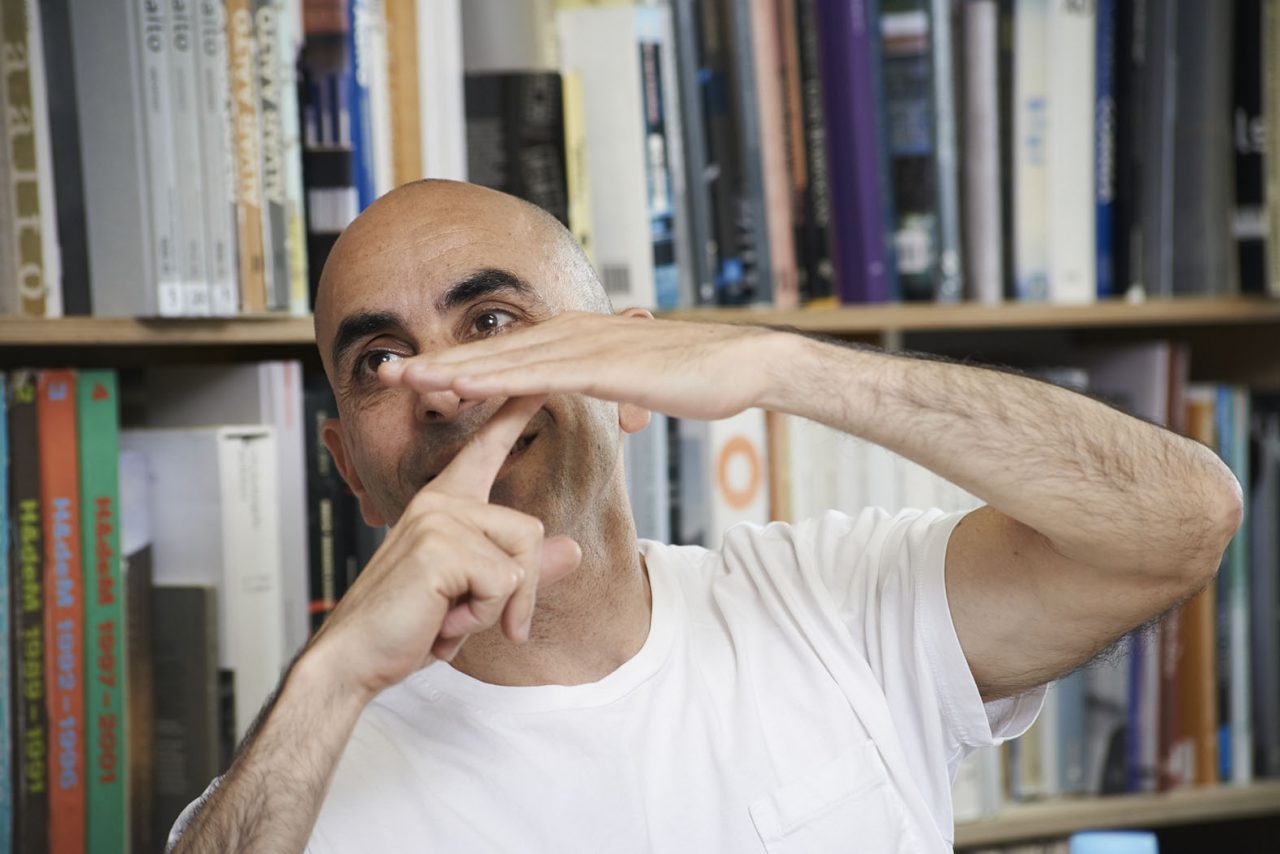

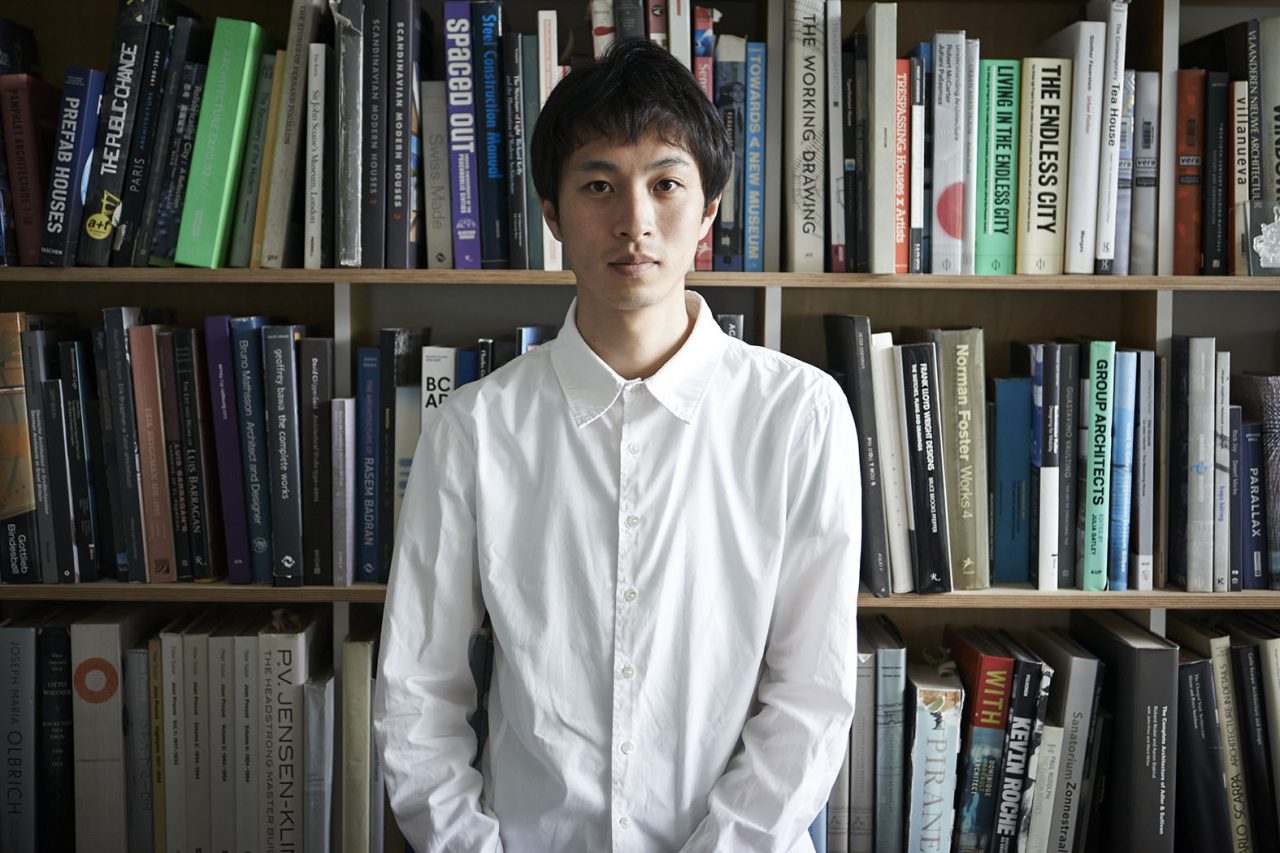

Nader Tehrani is an Iranian-American designer who has completed numerous architectural projects worldwide. Having served as the Head of the Department of Architecture at MIT from 2010 to 2014, he is now the Dean of the Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture of the Cooper Union. He is interviewed by Fuminori Nousaku—a Japanese architect who has drawn attention as one of the participating architects of the Venice Biennale 2016—about the future of “windows” in the context of drastically evolving technologies.

Fuminori Nousaku (hereinafter referred to as Nousaku): How do you think that windows can be changed through new technologies and materials, and at the same time, how can windows connect to modern technologies where architectural intelligence has been cultivated throughout human history?

Nader Tehrani (hereinafter referred to as Tehrani): I suppose there are many ways of responding to this. First, from a technological point of view, the advances already made about the transmission of cold and heat—helping to separate the inside from the outside—has had a huge impact; in this vulnerable moment where energy is so much part of a larger cultural cause, you can imagine that the reduction of energy use could have even more radical implications.

The majority of the loss of energy in buildings happens at the fenestration, not in the wall section—either because the wall section has insulation or sheer mass- both of which mitigate the potential of loss. So, one cannot underestimate the importance of the role of the window as a piece of technology.

But also the window, as framed in your question, is also not merely a sheet of glass, but can be seen as a conceptual space in itself. So, how you define that space may give it other cultural opportunities. But also the window, as framed in your question, is also not merely a sheet of glass, but can be seen as a conceptual space in itself.

For example, the English Bay Window is not just fenestration. It’s a social space, like an inglenook, as the threshold between the inside and the outside. It partakes in the social decorum of engaging the street while being on the interior. The corollary to that in Islamic culture, albeit fundamentally differently, is the mashrabiya, whose patterned woodwork not only protects the interior from the sun, but also created a protected space, an extension of cultural conventions that separate the private from the public domain, spaces of men and women, and other such proprietary protocols.

In other words in different cultures, the idea of fenestration has a section that works in relationship to customs, rituals and other social motivations, often mediating between the public and the private. So, I think that the way you insert culture into the question may be important.

The arena of technologies has also expanded its range from the traditional domain of the material sciences to engage at the nano-scale—effectively, how to transform the performance of the window-wall in relation to moisture, light infiltration, the passage of air, and insulation, without necessarily adopting the sheet products that are conventional composite of wall sections today. So, this is a piece of research that clearly is already underway.

Nousaku:You mentioned the nano-scale in relation to new technologies. Will windows inherit the current form that has been historically or culturally cultivated, or will they be changing rapidly with these new technologies?

Tehrani:By operating at the nano-scale, and the adoption of new materials, one can potentially develop infinitely small relationships in the constitution of new products that, for instance, may react to the heat and cold at the cellular level. If you look at some of the research of Skylar Tibbits and the Self-Assembly Lab, among other people interested in the behavioral quality of materials, there is much research being done in this arena; you can imagine that, over time, we may be able to gauge the properties of certain materials and how they react to wind, air, moisture and temperature, and to imagine that much can be optimized if seen through a micro-lens that is much more targeted.

Think of the windows of airplanes today. They have actually eliminated the physical blinds. The glazing darkens and lightens as per electronic triggers -a sort of reactive—or interactive—digital curtain.

Nousaku:Can this process of research keep the culture of historical forms or can it be changed?

Tehrani:Both, why not. My question to you is why we should see history and the contemporary world in such dichotomous ways. One’s ability to absorb culture projecting into the future should find its expressions through the clothes we wear, through the environments we inhabit, and through the practices that we take on. Consider, for example, the new ELSI building (“Earth-Life Science Institute”), the one just unveiled by Yoshiharu Tsukamoto on Tokyo Institute of Technology campus.

-

Hinman Research Building ©Johnathan Hillyer

-

Hinman Research Building ©Johnathan Hillyer

The idea of the elimination of curtains and many others things through the screens on the interior is something of that nature. It is not done in a nostalgic way, but it is clearly part of a Japanese tradition of constructing a veil through the screens that, at once, protect the building environmentally but clearly also have a social function—while constructing a space for modernity here. It is also not fabricated out of wood, but rather aluminum, and they are very much in sync with the character and language of the building at large.

Nousaku:The screen is what we call shoji, Japanese traditional paper screen. However its frame is now replaced by aluminum and the paper by Warlon sheet, translucent synthetic material. Since paper is very weak, it is coated with plastic, protecting the paper from wear and tear. People simply used to repaper the screen before such material appeared. Moving onwards, windows are mainly produced in the factory, in order to regulate standards of performance: its hardware, airtightness, waterproofing, and so on. How do you think new technologies and materials will change the window industry?

Tehrani:If you look at contemporary buildings, more and more, the compartmentalization of the building industry is beginning to collapse. So, often we no longer separate the wall materials from the windows, waterproofing, and insulation. Some of the more sophisticated buildings are beginning to integrate these into one collective strategy. Part of this results in a pre-fabrication of the entire system off-site with optimized ways of installing them.

This results in the potential customization of certain segments of the building without the premium cost that it would conventionally involve to build it. But effectively it puts an end to notions that different industries are working independently to optimize their own terms.

I think that an integrated systems approach is certainly one way in which this technology is changing and you can see it in the way that certain buildings are being manufactured. Consider the “Simmons Hall” at MIT designed by Steven Hall, or Frank O. Gehry’s “MIT Ray & Maria Stata Center” just down the street from it, both of which were conceived, fabricated and installed with this process in mind.

I think from a point of view of interactive environments—spaces that react to wearable technologies, or your smartphone, being able to program the heating and cooling of your apartments before you get there is another thing that is clearly starting to take place. It’s not uncommon to have apps that customize your environment.

So, part of that is also imbedding smart systems within context of the window knowing where, for instance, there is heat build-up in the morning or afternoon and protecting the house remotely from it. Thus, being able to speak to your window and having the window talk back to you is part of this technological shift that is already occurring.

Current double-glazing separates the inside and outside by way of an interstitial void filled with argon. What if the cellular composition of the glass itself had ʻbubbles’ in it, creating a more insulated mass? I wonder how much more that could optimize the system? Consider NASA’s work with Aerogel, and the composition of Silica, that is its base.

So, even at the nano-scale, the idea that glazing can be insulated means that (A) you are using less material. (B) You are using the material in an optimized way because the function of air is doing a lot more for you than it would be conventionally.

As I understand it, Japanese law has not caught up with all of the energy efficiency level requirements of other countries, (or the fire regulations) so there is some work that needs to be done on that front also.

Nousaku:As the industrial society has been growing bigger than before, high technology based on science sometimes could be harmful to human life. Considering that high technology will play a larger role in the future, what should architects do for maintaining the quality of life?

Tehrani:I think technological advancement can be made in such a way to internalize the forces of both the Sciences and Humanities; they can serve as a conduit through which we study our potential to react to our requirements for optimization on the one hand, but also mediated by our cultural needs, not to mention the more individuated sense of desire or pleasure.

These technological changes are not abstract. They are also purposeful and engage in our lives in different ways as need be. So, it may be that science does not get the upper hand in this equation, but only one part of the dialogue. Why don’t you think that culture has a deep-seated way of manipulating technology?

Nousaku:The network of things has become more complicated because the globalization has made us accessible to the distant things. I think the local and small network are also important for us in order to make a recovery from managed society with high technologies and to build the quality of life by ourselves.

Tehrani:In places like Japan and the USA, where industries are quite advanced, the role of products has the tendency to overwhelm architectural opportunities, especially in areas of potential invention.

While in developing countries, you can take advantage of both types of manufacturing cultures at once large scale manufacturing and local and/or small scaled industries that can build to fit. In the USA, we often feel a lack of access to craft, or to areas of speculation that one can undertake in less developed places in the world.

For architects, those end up being a much more productive arena in which to operate if you want to invent details. For me, the power of the architect in the context of your question has to do with his or her ability to take reign over the means and methods of construction rather than just design abstractly.

I don’t know if this is true in Japan, but within the legal construct in the United States, there is the architect, the contractor, and the client—and the architect is responsible for design intent, but does not have a final say over manufacturing procedures. The contractor is responsible for the means and methods of construction—which divorces the architect from their ability to enforce a detail, alienating them from an arguably most powerful realm of architectural speculation.

I don’t know if this communicated well, but I find this to be the most important argument that can be made in the context of your question.

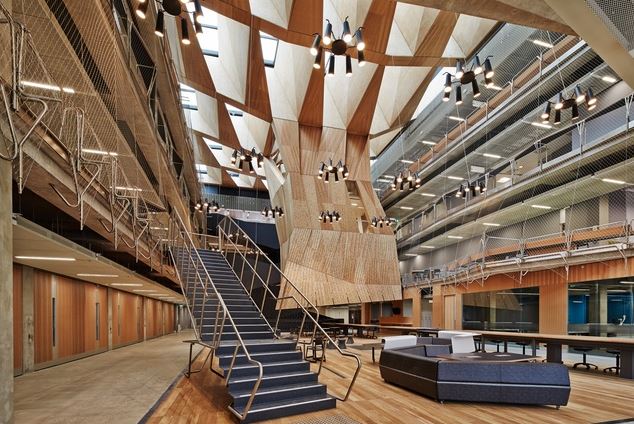

Nousaku:Could you tell us about the most important characteristic of windows you have used in your project and what was the intention when you designed the project? For example, I think the skylight of “Melbourne School of Design” (2014) is very unique.

-

Melbourne School of Design ©John Horner

-

Melbourne School of Design ©Roland Halbe

-

Melbourne School of Design ©Roland Halbe

Tehrani:It may be helpful to cite the different ways in which windows or apertures operate.

While window suggests a stable ʻtype’ or product, the aperture suggests a more abstract notion, and leaves room for interpretation, transformation and invention. Design opportunities require this shift in thinking, if only to determine when convention is at play and when a certain surplus of conceptual effort is required.

So, for instance, in the Melbourne project, there is a large field of skylights over the main hall. However, we wanted the glazing and their requisite frames to have a minimal impact on the character of the space. Why? Because we wanted the structure -which is primarily made of wood- to dominate, not only defining the space, but its structure, apertures, and character of the heart of the building.

-

Melbourne School of Design ©Roland Halbe

-

Melbourne School of Design ©Peter Bennetts

Even though it required a sophisticated detail for the glazing that could shed the water all in one direction, collecting water into a cistern, it appears that we have eliminated glass because we amplified the wood coffers in the foreground.

We designed a window to disappear. For the base of the “Samsung Model Home Gallery” (2012), we wanted the interior of the building to be an extension of the adjoining park.

The window glazing is not designed as a standard or stable frame, but rather it is dimensioned in variable widths such that it has the ability to densify in relationship to increase sun on the south orientation, while open up on the north; as such, the vertical struts of the window mullions appear as abstract fields, a conceptual barcode that fluctuates depending on location.

-

Samsung Model Home Gallery ©John Horner

At the same time, the base of the windows is recessed into the ground, eliminating its presence, as it were. To reinforce this, we used the same granite pavers of the sidewalks on the interior of the lobby, and s such, one sees the interior and exterior as an extension of the same landscape.

This is obviously not a new detail and we have seen many architects, such as Mies van der Rohe, exercise this, but the idea that the window helps to connect the inside and the outside, whether representationally or symbolically, is a powerful way of overcoming the autonomy of the architectural object, making it an extension of the landscape.

-

Samsung Model Home Gallery ©John Horner

This is also something we adopted in the Saint-Tropez house (“Dortoir Familial”, 2011). There, we have a wall of glass that is about 20 meters long and each panel is about 2 meters wide and you can take all of those panels and slide them all in one end —thus doubling the living areas of the interior as they extend outside.

In environments where the temperature is good for 6 to 8 months of the year, it also means that one can design a relatively modest footprint, knowing its dimensions can be doubled in the warm months. In this context, the window system is designed to disappear.

Contrary to this, you get projects like the “New England House” (2002) or the “New Hampshire Retreat” (2014) where the zone of the window is not necessarily only to connect the inside and the outside but is a transitional space that you occupy between the two sides.

In other words, you can thicken that zone and then the window becomes a room in itself. I think that’s a distinct opportunity that we have tried to undertake connecting windows with furnishings within a poché space, of sorts. For instance in the “D.C. House” (“Rock Creek House”, 2015), the chaise lounge is embedded into the window, so you literally sleep in the window. You don’t look through the window. You sleep in the window and your ability to inhabit the window has a different kind of opportunity.

-

D.C. House ©John Horner

-

D.C. House ©John Horner

Nousaku: We found the same concept in India. The window is not simply a sheet of glass. It’s the bed with the window integrated. The window is made of wood lumber. Here, we call it sleeping window. It’s designed by Studio Mumbai.

Tehrani:Yes, very beautiful, fantastic…and a great architect.

Nousaku:We want to research NADAAA’s window.

Nader Tehrani Nader Tehrani is the Dean of the Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture at the Cooper Union, and he is also a Principal of NADAAA, a practice dedicated to the advancement of design innovation, interdisciplinary collaboration, and an intensive dialogue with the construction industry. Tehrani’s more recent efforts have been to bring his interest in material culture to inform spaces of learning, especially in an age where online education and new technologies are impacting emerging forms of pedagogy; these efforts include three Schools of Design: the Hinman Research Building at the Georgia Institute of Technology, the Melbourne School of Design at the University of Melbourne, and the Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design at the University of Toronto.

http://www.nadaaa.com/

Fuminori Nousaku Born in Toyama prefecture in 1982. Graduated from Department of Architecture and Building Engineering at Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2005. Finished Master course at Department of Architecture and Building Engineering at Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2007. Worked at Njiric+Arhitekti from 2008. Established Fuminori Nousaku Architects in 2010. Finished Doctor course of Department of Architecture and Building Engineering at Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2012. Assistant professor of Department of Architecture and Building Engineering at Tokyo Institute of Technology since 2012.

http://nousaku.web.fc2.com/