Articles Windows of Japanese Modernist Architecture

The Windows of Tomoya Masuda’s Naruto Cultural Center: A Faintly Bright Louvered Space

17 Jun 2025

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Columns

- Essays

The Naruto Cultural Center is a posthumous work by architect Tomoya Masuda. It is one of several buildings that the former Kyoto University professor designed in Naruto, Tokushima. Takahiro Toji, author of Tomoya Masuda’s Architectural World (Eimei Information Design, 2023), provides his reading of the building’s foyer—a concrete space with a unique quality of light, produced by its distinctive vertical louvers—based on Masuda’s architectural philosophy.

Note: The building is closed as of 2024 due to seismic retrofitting work.

While Naruto is known for its whirlpools, the churning currents are found only in the Naruto Strait. Along the coasts where the waters are calmer, salt fields once spread across the land. Cutting through the flat landscape, the canal-like Muyagawa River—appearing almost still—tranquilly mirrors the Naruto Cultural Center (1982).

Casting an austere, temple-like air, the exposed concrete building forms what might appear to be a sacred complex together with the neighboring Naruto Center for Health and Social Welfare1.

The Cultural Center was designed by Tomoya Masuda (1914–1981), who practiced architecture while teaching for many years at Kyoto University. Although I have heard that he was compared to his Tokyo-based peer Kenzo Tange with the moniker “Tange of the East, Masuda of the West”, Masuda’s designs have long remained largely unknown. He is perhaps better remembered for his dense theoretical writings, which draw on the ideas of Dogen and Heidegger. As challenging as his texts may be to decipher, however, the goal of Masuda’s creative pursuit is clear: to realize a distinctively Japanese architecture using reinforced concrete. While Japanese architectural discourse shifted from tradition in the 1950s to Metabolism in the 1960s, followed by Postmodernism in the 1970s, he remained focused on realizing modern designs grounded in the nation’s architectural heritage. Completed a year after his passing, the Naruto Cultural Center represents the culmination of this pursuit.

-

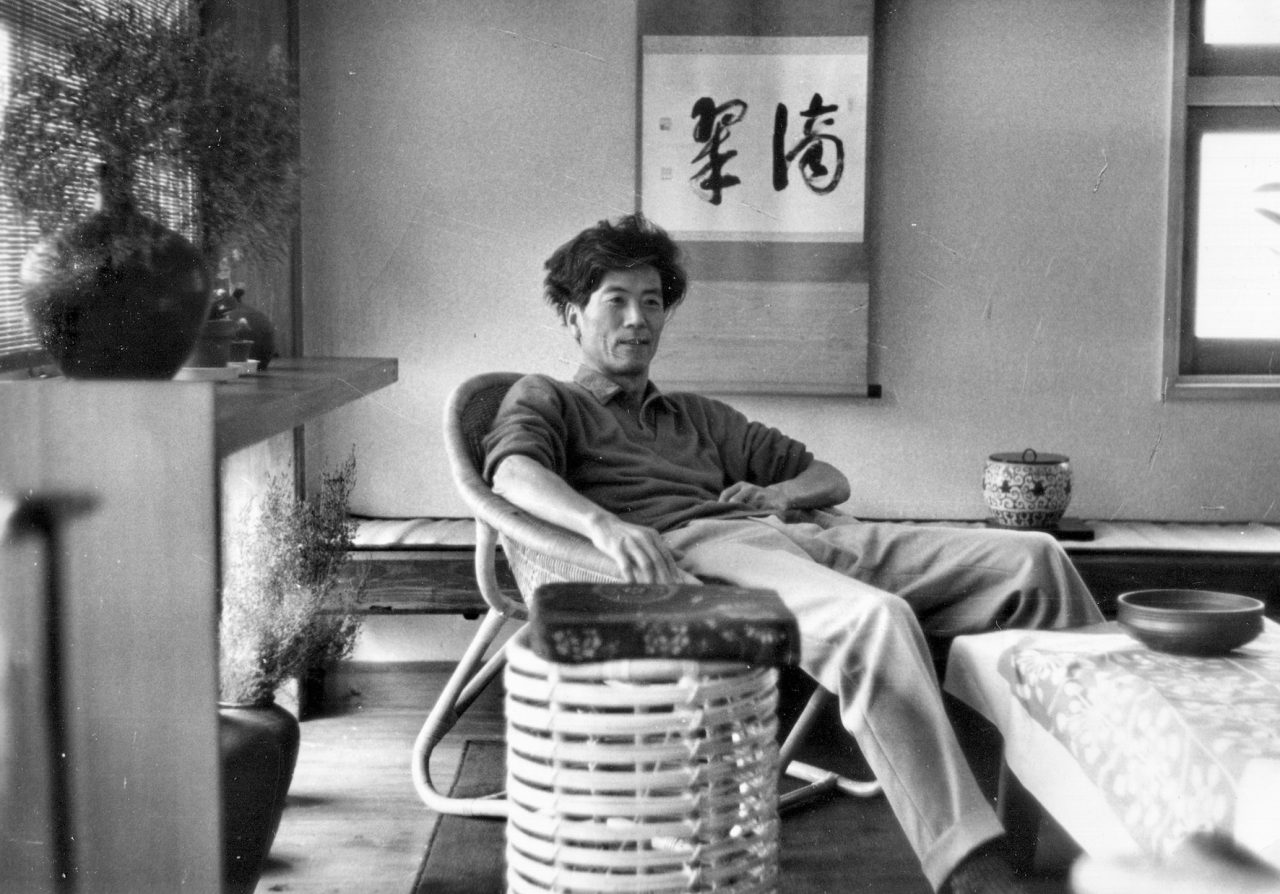

Tomoya Masuda relaxing in his home. Photo courtesy of Hidehiko Watanabe.

Masuda’s architectural philosophy was initially centered on the view that buildings are composed of isolation walls. Later, as he delved deeper into his research on Japan’s historical architecture, he came to conceptualize the dualistic quality of traditional spaces shaped by deep eaves and daylighting shōji [translucent screens]—spaces in which interior and exterior are at once separated and continuous—as manifesting a condition of semi-isolation. He also explored such spaces in his design work, which led him to adopt the technique of louvering.

Upon arriving in front of the Cultural Center, one ascends a gently sloped ramp, passing beneath a massive concrete gate. The building is elevated on roughly two meters of additional fill laid over a reclaimed salt field. At the top, the view opens onto a court bounded along the south by the Cultural Center and along the north by the Welfare Center—also designed by Masuda—and extending toward the Muyagawa beyond. Although the paving tiles lend the space a hard-edged quality, it is scaled just right: not too large, but comfortably intimate. It brings to mind the court of Louis Kahn’s Salk Institute (1965), yet feels even more strict and austere. This is undoubtedly due to the powerfully articulate exposed concrete louvers lining the façades of Masuda’s two buildings.

Protruding into the court, the Cultural Center’s entrance canopy has a clearance height of just 2,225 millimeters. Passing beneath it and through the entrance doors brings one into the light-filled foyer, which immediately expands to nearly 10 meters in height. An array of columns, arranged on a 7,200-millimeter square grid, rises easily through the cavernous space to support a lattice of beams. The columns, cruciform in plan and narrower at the base, and the beams, which also taper downward, give an enhanced impression of slenderness. The aforementioned louvers are set off by 1,200 millimeters around the perimeter of this structural framework.

-

Entrance. -

Louvers of the east façade.

The louvers are also spaced at 1,200 millimeters, or one-sixth of the column spacing. Measuring just 150 millimeters across their faces, they appear exceptionally thin relative to their height. These dimensions were chosen using a proportioning system2 inspired by Le Corbusier’s Modulor. In fact, the dimensions throughout the building are governed by the same logic. Yet the foyer conveys no sense of overt intellectual abstraction; rather, it is graced with a pleasant sense of rhythm and ordered harmony. The louvers diffuse the sunlight that filters through their glazed openings, suffusing the space with a gentle, bright ambience. The diffusion of light is aided by the coarse joints imprinted on the louvers’ surfaces as a result of casting the concrete with 1-by-6-shaku [approx. 303-by-1,818-millimeter] planks rather than formwork panels. The same louvers that present a hard, austere look to the outside thus impart a soft, faint brightness when seen from within. The stark contrast between the exterior and interior is both surprising and moving when experienced in person.

The luminous panels incorporated into the foyer’s high ceiling do not detract from the soft ambience; if anything, they enhance it. Each fixture consists of sixteen milky-white acrylic panels, arranged in a 4-by-4 grid within the beam lattice. Together, they create a subdued, uniform glow across the ceiling. Downlights are used only sparingly to prevent sharp beams of light from disrupting the space.

-

The luminous ceiling of the foyer. Photo: Yasushi Ichikawa

The faint brightness flows continuously throughout the foyer with subtle shifts in nuance. A scattering of accent lights adds to its richness. Seen first is the golden louvered window, visible directly ahead upon entering. Its louvers are specified as white in the building plans, so it seems the decision to change their color was made on site. In addition to being gold, they differ from the others by being angled, such that the glazing is mostly hidden when the window is viewed head-on. Glimmering softly as light washes laterally across their surfaces, they evoke a ceremonial folding screen, adding a fitting note of vibrancy and frontality to the serenely lit foyer.

The eastern louvered façade incorporates a stretch of solid wall featuring a “colored-light window”. Composed of four slits, the ornamental window adorns the wall like a piece of jewelry. Another colored-light window can be found in the corridor linking the lobby to the hall’s seating area. Inspired by the “wall of light” at Le Corbusier’s Ronchamp Chapel (1955), its four uniquely shaped apertures, fitted with red, blue, yellow, and green acrylic panels, add a festive flair to the approach to the hall.

In contrast to the foyer, the adjoining lobby is vertically compressed to 2,750 millimeters and suffused with a faint darkness. It has a coffered ceiling made entirely of exposed concrete, yet with beams measuring just 85 millimeters wide at the face and 325 millimeters deep, it could almost be mistaken for millwork. The gridded ceiling design is echoed in the three-panel daylighting shōji fitted to the windows. Each window spans 4,800 millimeters—the equivalent of four louver gaps rather than the full 7,200-millimeter column spacing—and is visually separated from the louvers by vertical slit openings. Masuda employed this technique of delineating openings from the structural framework in many of his works. The slits recreate the same condition of semi-isolation achieved by the shōji of traditional Japanese homes, which can be slid open slightly to admit a sliver of the outside.

-

Lobby. The coffered ceiling is made of exposed concrete.

After starting out with the view that architecture is reducible to isolation walls, encountering traditional Japanese architectural spaces that blur the distinction between inside and outside, and then formulating the concept of semi-isolation to describe these dualistic spaces that challenge the Western conception of the wall as separator, Masuda developed a fascination with the indescribable ambience evoked by the “faint brightness” and “faint darkness” observed within them.

As illustrated by Junichiro Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows, any Japanese person will be familiar with the nuances of a space rendered with subtle lighting. Many architects have also spoken of achieving a distinctively Japanese quality of light. Masuda, however, took this idea a step further: he perceived the faint brightness and faint darkness of Japanese spaces as embodying nature.

Grasping what Masuda means by “nature” is one of the more challenging aspects of his architectural philosophy. He explains it through Muso Soseki’s rock garden at the temple of Saihoji (Kokedera), describing how its composition of cascading rocks, which represents flowing water, is, on a deeper level, an expression of nature itself.3 He then cites the following Zen phrase by Dogen:

“Mistake not the true world of mountains and rivers as merely a world of mountains and rivers.” (from the Shōbōgenzo [Treasury of the True Dharma Eye])

The “world of mountains and rivers” refers to the physical, visible elements of nature—rocks, trees, water. The “true world of mountains and rivers”, as Dogen distinguishes it, refers instead to the natural state of being—or in other words, nature as a fluid, ever-changing force.

The rocks in the garden thus give expression not only to flowing water but also to nature’s fluidity and ceaseless flux. Could the same be achieved with the faint brightness or darkness suffusing the spaces of a building? This was the idea that Masuda attempted to realize with the light diffused by the concrete louvers. The unique ambience of a faintly bright or dark space, and the beauty of light’s subtle shifts, have a way of stirring the human soul. We are undoubtedly moved by these things because we perceive through them nature’s fluidity and movement. Viewed through this lens, the faintly bright louvered space of the Naruto Cultural Center splendidly manifests the essence of Masuda’s architectural philosophy.

Notes

1:The two buildings, constructed successively, originally housed the Working Youth Home (1975) and Senior Welfare Center (1977).

2:The system is based on a standard measurement of 7,200 millimeters and comprises the following series of values, derived from a combination of the golden ratio and Fibonacci sequence: 7,200/4,450/2,750/1,700/1,050/650/400/250/150.

3:Tomoya Masuda, Masuda Tomoya Chosakushū III: Ie to niwa no fūkei [Tomoya Masuda Collected Works III: Home and Garden Landscapes] (Nakanishiya, 1999).

Takahiro Taji

Born 1962 in Kumamoto, Japan. Professor, Department of Architecture and Architectural Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Kyoto University. Doctor of Engineering. Specializes in architectural theory and architectural design. Currently supervising the renovation projects of the Naruto Cultural Center and Naruto Center for Health and Social Welfare. Authored publications include Igirisu fūkei teien [The English Landscape Garden] (2000). Edited publications include Kankyō no kaishakugaku [Environmental Hermeneutics] (2003), Nihon fūkeishi [History of the Japanese Landscape] (2015), Bunriha Kenchikukai [The Bunriha Architecture Group] (2020), and Tomoya Masuda’s Architectural World (2023). Architectural works include the Sekisui Chemical Kyoto Technology Center (1991; designed as a member of the Kyoto University Kunio Kato Laboratory), Villa Kujoyama (1992; id.), Waterras Student House (2013), and Miwayama Kaikan (2019).

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Windows of Japanese Modernist Architecture

A Culmination of Sutemi Horiguchi’s Aperture Designs:

The Tokoname City Municipal Ceramics Research Institute (Tokoname Tounomori Research Institute)15 May 2025

Windows of Japanese Modernist Architecture

The Diversity of Windows in Kiyonori Kikutake’s Serizawa Literary Center (Serizawa Kojiro Memorial Museum)

25 Dec 2024

Windows of Japanese Modernist Architecture

The Windows of Hiroshi Hara’s Awazu House: Spaces of Light Illuminating the Darkness

26 Apr 2024

Windows of Japanese Modernist Architecture

Windows of the Aichi University of the Arts

by Junzo Yoshimura and Akio Okumura:

The Concrete Science of Living with Nature19 Jan 2024