Series Terunobu Fujimori’s One Hundred Windows

Terunobu Fujimori | 003: The Vertical Sliding Windows of the Public Speaking Hall (Mita Enzetsukan)

24 Aug 2022

- Keywords

- Architecture

- Essays

- History

- Japan

In this series, architectural historian and architect Terunobu Fujimori, who has traveled extensively to study buildings of various times and places, will be introducing a selection of notably intriguing windows found in historic buildings from all across Japan, one at a time. In article number three, he discusses the vertical sliding windows (agesagemado) of the Public Speaking Hall on the Keio University Mita Campus. The hall was created by Yukichi Fukuzawa as a space for practicing the Western act of “speech”—a term that he is also credited for introducing to the Japanese vocabulary—and it is an example of a so-called “quasi-Western-style” (giyōfū) building dressed with a distinctive plaster-and-tile finish.

Japan’s traditional architecture did not have windows as we picture them today. It could not have been otherwise, for glass, the key component to the glazed openings that you no doubt imagined upon reading the word “windows”, did not exist in premodern Japan. Now, some of you will surely immediately point to Satsuma or Edo kiriko [types of cut glass ware], the poppen [a toy whistle] depicted in Utamaro’s Poppen wo Fuku Onna [Woman Blowing a Poppen], the Hakururiwan [a cut glass bowl] preserved at the Shosoin [the imperial treasure house at Todaiji], or―if you are an archaeology enthusiast―the kudadama [tubular glass beads] or tonbodama [round glass beads] excavated from ancient tumuli as evidence to the contrary. However, all of these are examples of glass used strictly for arts and crafts, as opposed to plate glass used for windows.

Glass was extremely precious, so while it indeed was used for artisanal purposes, nobody in the world―save for the ancient Romans―could afford to use it for utilitarian products such as windows, which require large amounts of the material. Even the ancient Romans only Crown glass was eventually superseded by the stained glass of the great Gothic cathedrals, and then by modern-day window glass once the Industrial Revolution made it possible for glass to be cheaply mass produced.

Outside Europe, in places where there were neither ancient Romans nor an Industrial Revolution, premodern windows remained without glass. People instead made do by covering their windows with boards or paper. That was the context into which window glass was introduced from post-Industrial Revolution Europe. What followed is relatively well documented for a building material, but I will skip over its history here and specifically discuss the circumstances surrounding its early spread through Japan.

The first to make the leap was giyōfū [lit. “quasi-Western-style”] architecture. Kisuke Shimizu, a carpenter who was exposed to the glazed windows of the Western-style mansions that sprung up in the foreign settlement in Yokohama, teamed up with American architect Richard Perkins Bridgens to build the British Consulate in the port city. There they attempted to fuse Japan’s traditional architecture with the American frontier architecture that Bridgens brought with him, and brilliantly succeeded. Despite being made of wood, the building is Western style in its overall appearance, it has glazed windows, it is fairly well fireproofed, and it also has Japanese design features. A key point to note is that it was a design for Western-style architecture that Japan’s native carpenters were capable of constructing.

Following their success, the Bridgens-Shimizu duo managed to bring their locally-buildable Western-style architecture to the nation’s capital—freshly renamed from Edo to Tokyo—when they completed the Tsukiji Hotel in the new foreign settlement established in Tsukiji. The Tsukiji Hotel left a definitive impact on Japanese society, as the sight of the building was etched into the minds of not only Tokyoites who were unable to visit the foreign settlement in Yokohama, but also people in the provinces, who learned of it through woodblock prints.

At the time, the fledgling Meiji government was looking to announce the dawn of a new era to Japanese society in two ways. The first, of course, was by reforming the political system and economy as expressed by the slogan “fukoku kyōhei” [lit. “rich nation, strong soldiers”], and the second was by advancing the molting of old ideologies and culture, or “bunmei kaika” [lit. “opening up of civilization”]. Giyōfū architecture played a major role in advancing the latter agenda. As signified by the fact that the style was first manifested as a hotel, a stylish building type that did not previously exist in Japan, giyōfū became the go-to style for the various new kinds of buildings that were developed across the country not only by the government, such as public offices, schools, hospitals, post offices, and military barracks, but also by the private sector, such as banks and company offices.

Two marked external features of these buildings were “namakokabe” [lit. “sea-cucumber walls”] (a finish technique that combines flat tiles with raised plastered joints) and glazed windows. Glazed windows thus spread through Japan alongside namakokabe as part of the bunmei kaika carried out during the early part of the Meiji era (1868–1912).

Giyōfū buildings with namakokabe were built throughout the country, but there are very few surviving examples. In fact, there are only three: the Niigata Customs House from Meiji 2 (1869), the Public Speaking Hall at Keio University from Meiji 8 (1875), and the Iwashina School in Izu from Meiji 13 (1880). Let us look specifically at the Public Speaking Hall, which is the best example for considering windows.

The building was commissioned by Keio’s founder, Yukichi Fukuzawa, who wanted to share with Japan the importance of the political act of speech, which he witnessed firsthand during his time in the United States. As Keio was originally founded next to the foreign settlement in Tsukiji, it should be fine to say that this namakokabe giyōfū building is a direct descendent of the Tsukiji Hotel.

Keio’s campus was later relocated to its hilltop location in Mita, where the building makes a striking impression despite its modest size. Its namakokabe especially stands out against the green backdrop of trees. But of course it stands out. Nowhere else in the world will you find an architectural finish that lays white atop black, let alone in diagonal lines. White, black, and diagonals. When and how this un-Japanese finish that feels at once both plain and gaudy came to be is unclear, but it had been in use on the exterior walls of the daimyō [feudal lord] residences in Edo. I suspect that it was devised as a defense against fire for the castle architecture developed during the early part of the Edo period (1603–1868). Their use on the walls running along the top of the stone foundations of Kanazawa Castle is well documented (albeit there the plaster is oriented horizontally and vertically, not diagonally), but I do not know of any other examples.

-

Front facade of the Public Speaking Hall.

-

North facade.

-

An agesagemado on the side facade (closed). -

An agesagemado on the side facade (open).

The plain/gaudy walls of the Public Speaking Hall that make for an unforgettable sight have vertical rectangular glazed openings, which are designed unassumingly using a type of window that may go unnoticed at first glance: the agesagemado [lit. “up-and-down window”; i.e. vertical sliding window, or sash window].

Giyōfū architecture began its evolution from half-timber-style giyōfū, which incorporated namakokabe, reached its peak with the plaster-style giyōfū that followed, and saw a phase of clapboard-style giyōfū before it eventually died out. However, the agesagemado remained the main type of window across all the variants. Japanese carpenters should have had plenty of knowledge at the time about double-swing windows like those still in use today, so what was the reason for their preference for vertical sliding windows? When I asked myself this question, it occurred to me that I did not know where in Europe or America vertical sliding windows came from in the first place. I scrambled to find an answer in the books I had on hand, but I came up empty. Perhaps they are connected somehow to the American Frontier days.

-

The agesagemado on the side wall.

There are three ways of making an agesagemado. The easiest is to make it so that the lower sash can be slid up and held in place by a catch when fully raised. This is a light, easy, and sufficiently waterproof solution.

For larger windows that would require one to have more arm strength to lift the sash, a pulley threaded with a cord connected to the two sashes can be installed at the top of the window. Raising the lower sash causes the upper sash to slide down, so the weight of the sashes is canceled out. The way the glass overlaps at eye level, however, can be rather annoying.

The most sophisticated method is to install weighted pulleys inside the upper left and right parts of the window frame, as is done at the Public Speaking Hall. I recall being puzzled by the rattling sound that one such window made when I conducted a survey of a clapboard-style giyōfū building as a student, but then I figured out the mechanism once I peered into a break in the window frame and found a round metal rod attached to a cord that moved up and down with the sash. I was awed by the power of the design that was able to perform properly even after more than a century.

-

Cord and pulley on the side of the agesagemado.

-

Crescent lock. -

Metallic handle.

Now, to go back to my earlier question: Why did the carpenters of the early Meiji era have a liking for vertical sliding windows? The answer may simply be that these windows that move vertically, as opposed to horizontally like Japan’s traditional shōji [paper-covered lattice screens] and itado [wood board doors], piqued their curiosity.

Project Overview

Public Speaking Hall (Mita Enzetsukan)

Architect: Unknown

Location: 2-15-45 Mita, Minato, Tokyo, Japan (Keio University Mita Campus)

Year Completed: 1875 (Meiji 8); relocated in 1924 (Taisho 13)

The Public Speaking Hall was commissioned by Yukichi Fukuzawa as Japan’s first-ever speech hall. The two-story giyōfū-style wooden building has a tile roof and namakokabe, and it was built based on plans brought in from the United States. The hall originally stood between the Old Keio University Library and Jukukankyoku buildings before it was relocated to its current site in 1924 (Taisho 13). It is one of the oldest surviving works of Western-style architecture in Tokyo and was designated as an Important Cultural Property by the Japanese government in 1967 (Showa 42).

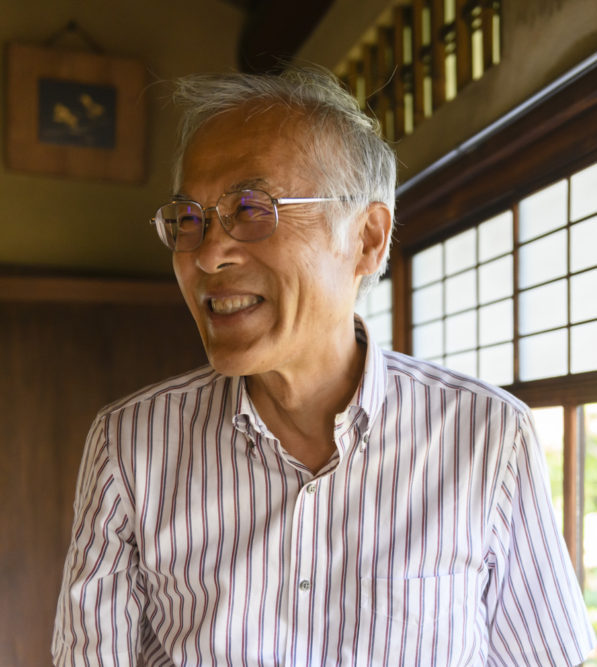

Terunobu Fujimori

Born 1946 in Nagano, Japan. Completed a doctorate at the University of Tokyo (UTokyo). Served as a professor in the Institute of Industrial Science at UTokyo and at Kogakuin University. Currently a professor emeritus of UTokyo, a specially appointed professor of Kogakuin University, and the director of the Edo-Tokyo Museum.

Began designing buildings at age 45. Has authored numerous publications related to architectural history, architectural investigation, and architectural design.

Recent publications include Arata Isozaki and Terunobu Fujimoriʼs Discussions on Tea-House Architecture* (Rikuyosha) and Western-Style Architecture of Modern Japan*(Chikumashobo).

Has designed many history museums, art museums, houses, and tea houses. Recent works include the Grass Roof and Copper Roof (Taneya Main Shop and Headquarters, Omihachiman)

MORE FROM THE SERIES

-

Terunobu Fujimori’s One Hundred Windows

Terunobu Fujimori│008: The Ribbon Window of the Karuizawa Summer House—

The Modernists’ Dream, Realized in Japan20 Mar 2025

Terunobu Fujimori’s One Hundred Windows

Terunobu Fujimori│

007: The Shōji of the Rinshunkaku01 Feb 2024

Terunobu Fujimori’s One Hundred Windows

Terunobu Fujimori│

006: The Shitomi of the Kondo Hall at Ninnaji Temple12 Sep 2023

Terunobu Fujimori’s One Hundred Windows

Terunobu Fujimori│005:

The Katōmado of the Shizutani School Auditorium: An Un-Japanese Japanese Window05 Jul 2023